What is Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ?

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), also known as intraductal carcinoma, is a type of non-invasive breast cancer. This means it involves the abnormal growth of cells but these cells are still contained within their original layer, known as the basement membrane. If these cells break through this layer, then the condition is diagnosed as invasive breast cancer. Many consider DCIS as a possible early form of invasive breast cancer. In fact, the World Health Organization describes DCIS as an unusual growth of cells that are found within the milk ducts of the breasts, which has the potential to progress to invasive breast cancer.

But remember, not all DCIS conditions are the same. They can vary in how they appear, their genetic make-up, their associated biomarkers, their physical characteristics, and their likelihood to develop into invasive breast cancer. With improved breast screening methods, we’re now detecting more cases of DCIS, especially those which show tiny deposits of calcium. But, to correctly diagnose DCIS, a tissue sample or biopsy is needed. When it comes to treatment, healthcare providers usually use a combination of treatments which can include surgery, hormone therapy, and radiation therapy.

What Causes Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ?

The process through which normal breast tissue turns into a type of breast cancer known as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is not fully understood. Some people with DCIS have a genetic predisposition to it, especially those with mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. However, this isn’t the case for everyone who develops this condition.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer among women in the United States. A specific type of breast cancer known as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is especially prevalent in women aged 50 to 64 years. About 20% to 25% of breast cancer cases in the United States are DCIS. Despite the fact that DCIS was not as commonly diagnosed before the introduction of screening mammography, it is often detected through these screening tests today.

A 2020 study found that if DCIS is left untreated, it can develop into invasive breast cancer in 36% to 100% of cases within a timeframe of 0.2 to 2.5 years. This study also revealed a wide range of possibilities when it comes to overdiagnosis, something that requires further research due to the diverse subtypes within DCIS.

There are several risk factors that can increase the chances of DCIS turning into invasive breast cancer. A woman’s lifetime risk of developing invasive breast cancer is 12.3%. Also, high exposure to estrogen can increase the risk. Hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women and high natural levels of estrogen, determined by factors such as age at first menstrual period, age at menopause, and age at first pregnancy, can also contribute to the increased risk. The risk also increases with alcohol use and if you have first-degree family members with breast cancer.

- Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in the U.S.

- DCIS, a type of breast cancer, is common in women aged 50 to 64.

- About 20%-25% of diagnosed breast cancers in the U.S. are DCIS.

- DCIS is often detected through mammography screening.

- If not treated, DCIS can become invasive breast cancer in 36% to 100% of cases within 0.2 to 2.5 years.

- The lifetime risk of a woman developing invasive breast cancer is 12.3%.

- High exposure to estrogen, hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women, high natural levels of estrogen, alcohol use and having first-degree relatives with breast cancer are risk factors for breast cancer.

Signs and Symptoms of Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

The evaluation of patients with suspected ductal carcinoma in situ, a type of breast cancer, involves the collection of a detailed medical history and a thorough physical examination. Regardless of the main reason for their visit, these patients will need to provide baseline information.

- When they started menstruating (age at menarche)

- Number of pregnancies they’ve had

- Number of children they’ve given birth to (live births)

- Age when they had their first child

- If they have a family history of breast cancer or any other types of cancer

- If they’ve had any breast biopsies in the past

- Whether they drink alcohol

- For postmenopausal women, how long they’ve been using hormone replacement therapy

- For premenopausal women, if they use oral contraception

If a patient has a high risk of hereditary breast cancer based on their family cancer history, they should be provided with genetic counseling.

Even if patients don’t have any masses that can be felt, the physical exam is still very important. The exam should thoroughly check both breasts and armpits (axillae) for any signs of nipple discharge, changes in the skin, lumps, and swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy). Many women have their breasts examined after an abnormal result is found on a mammogram, a type of breast x-ray. There might not be any noticeable changes on the outside of the breasts, or the physical exam might find obvious abnormalities.

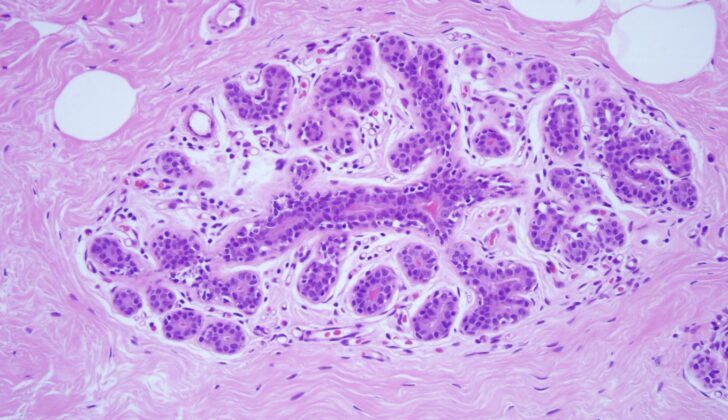

ductal carcinoma in situ, ruling out invasive carcinoma (x10).

Testing for Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

Ductal carcinoma in situ, a type of early-stage breast cancer, often doesn’t form a lump that can be felt. Instead, this disease is usually discovered through routine mammogram screenings, with about 90% of cases detected this way. If a mammogram screening shows a suspicious area, a more detailed mammogram is needed to check the specifics of the area and to see if the disease exists in both breasts.

A mammogram provides images of the breast, and it’s good at detecting possible cancers. Still, it’s not the best at confirming if an abnormal area is indeed cancerous. On mammograms, tiny, clustered calcium deposits (known as macrocalcifications) are a common sign of this type of cancer. These deposits, which can look like small white specks, tend to be tiny (0.1 to 1 mm in diameter) and normally group together. Deposits that display as linear branching patterns or odd segmental types are very likely signs of this cancer.

When these possible sign of cancer show up in a mammogram, it’s crucial to do more detailed mammograms. These can provide more extensive images and information to guide surgical planning if necessary.

An image-guided core needle biopsy, a procedure that extracts a small piece of tissue from the suspicious area, is vital to confirm the diagnosis. This method collects more tissue than a fine-needle aspiration, a similar procedure. This additional tissue allows doctors to find out if the cancer is invasive or noninvasive (like ductal carcinoma in situ). However, it’s important to remember that even this biopsy method has limits. For instance, when this biopsy shows ductal carcinoma in situ, there’s still a 10%-20% chance that this will turn into invasive carcinoma when the lump is fully removed in surgery.

The tissue sample collected during the biopsy is then checked to identify its hormone receptor status. Specifically, doctors look for the presence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2). These receptors are key to determine if specific hormonal treatments may be useful in reducing the risk of the cancer spread in patients.

Once confirmed, the necessary next step is surgery to either partially or completely remove the breast. This choice is based on the patient’s health history, results of the physical exam, and other factors such as how it may affect the appearance of the breast and the size of the cancerous area. It’s important to know about any factors that might prevent a patient from safely receiving radiation treatment after surgery. These factors, such as current pregnancy or a history of radiation therapy, along with the patient’s ability to attend follow-up appointments and their personal treatment preferences, should be identified during the initial evaluation after diagnosis.

Lastly, it’s important to find out if a referral for genetic counseling is needed based on the patient’s personal and family history. Some people may have a higher risk of developing breast cancer due to inherited mutations in certain genes. Those who find out they are at higher risk because of their genetics may prefer to have more of their breast tissue removed, possibly deciding on a mastectomy instead of a more conservative surgical approach.

Treatment Options for Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

Treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ, also known as DCIS, is multifaceted and typically involves a blend of surgery, radiation therapy, and hormone therapy. This plan is individually tailored based on the patient’s specific diagnosis and personal choices.

There are two main types of surgical treatment available for DCIS: breast-conserving surgery followed by radiation, or a complete mastectomy. Both options are considered effective, with similar long-term survival rates. Breast-conserving treatment, which involves partial mastectomy and radiation, is often recommended as it is less invasive. However, this approach is not suitable for patients with widespread disease, those who wouldn’t have enough remaining breast tissue for cosmetics, or those who can’t undergo radiation therapy. Mastectomy, on the other hand, is curative in 98% of DCIS patients, regardless of the size or grade of the tumor.

By nature, DCIS is noninvasive, and spread to axillary lymph nodes is uncommon. Therefore, a sentinel lymph node biopsy is not usually necessary during breast-conserving surgery. For patients who choose mastectomy for DCIS, a sentinel lymph node biopsy could be considered. This is because there’s a chance that hidden invasive breast cancer could be discovered, and performing this biopsy is often not possible after a mastectomy.

The medical management of DCIS primarily involves hormone therapy, typically prescribed to patients with ER-positive or PR-positive DCIS. Research shows that five years of hormone therapy can reduce the risk of the disease developing in the same breast or the other one. Some evidence also suggests that treating HER-2 positive patients with a drug called trastuzumab could have potential benefits. However, while some findings hint at a possible advantage, the results are not definitive and more research is needed in this area.

What else can Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ be?

It’s crucial to know that if a patient is diagnosed with a condition called ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), there’s a genuine chance that they might also have invasive breast cancer. Around 10% to 20% of DCIS cases, which are identified through a procedure called core needle biopsy, end up being classified as invasive cancer after further surgery (definitive resection). This is especially true for larger, severe DCIS cases, which are more likely to contain an invasive element.

Surgical Treatment of Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

Ductal carcinoma in situ, a type of breast cancer, requires a specific surgical approach. There are two main categories for this approach, namely breast conservation and mastectomy.

Breast conservation first involves finding the exact location of the lesion, which may not be felt by touch and might only show up in scans. Pre-surgery, an image-guided wire or tiny radioactive seed can be inserted to mark the lesion spot. The surgeon then uses these markers to precisely remove the lesion and a small surrounding area of normal breast tissue, ensuring a clean margin around the cancer. Once the lesion is removed, the tissue is checked via X-ray, with markers in place for future treatments like radiation therapy. It’s important the surgeon checks no concerning tissue remains in the breast after removal.

Post-surgery, the patient will need to have radiation therapy. The success of the surgery will need to be confirmed before radiation starts. This involves ensuring there’s a clean, cancer-free margin of at least 2mm around where the lesion was and taking a mammogram before radiation therapy starts. Regular scans and exams will continue after therapy. Reconstruction surgery can be considered after radiation therapy.

In the case of mastectomy, where the entire breast is removed, there’s no need to mark the lesion spot pre-surgery. But a sentinel lymph node biopsy, a test for spread of cancer, is highly recommended. Consideration for future reconstruction is important for the surgical planning of a mastectomy.

Mastectomy involves a broad area of dissection, which normally extends to the collarbone, sternum, below the chest, the side muscle and back muscle. Again, ensuring there’s no bleeding is important before closing the incision. Post-surgery, once adequate healing has occurred, discussions about breast reconstruction surgery can begin. The other breast will still need regular mammograms, and exams should follow the same schedule as with breast conservation.

What to expect with Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a type of non-invasive breast cancer, doesn’t usually cause metastases (cancer spread) or death when treated, making it rare. However, if not treated, DCIS can usually become an invasive form of cancer which could be fatal.

Patients with DCIS who are treated have a great chance of living a normal lifespan, but it’s worth noting that there’s still a slightly increased risk of dying from breast cancer with a DCIS diagnosis. A recent study in 2020 observed over 100,000 patients with DCIS and found that 20 years after diagnosis, 3.3% of patients died from breast cancer. This is three times higher than the general population’s rate and is the same regardless of whether they underwent breast conservation therapy or a mastectomy. Interestingly, this study also found that efforts to prevent the DCIS from becoming invasive by either radiotherapy or mastectomy didn’t reduce the chances of dying from breast cancer.

A review of many studies in 2019 found six factors that could increase the risk of DCIS turning into invasive breast cancer. These include DCIS detected during a physical exam, being in pre-menopause, having positive margins (cancer cells present at the edge of the removed tissue), high-grade DCIS, high levels of protein called p16, and being of African American ethnicity. These findings need further research for validation, but it provides insight into how diverse DCIS is. In the future, knowing the type of DCIS and its associated risk factors will be crucial in determining prognosis and treatment strategies to avoid both under and over-treatment.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

Complications can happen at any stage of treatment and they can vary in how often they occur and how serious they are.

Surgery can lead to various issues such as infection, large bruising, fluid-filled swelling, wound reopening, pain, arm swelling, collapsed lung (from placing a wire), death of skin flaps due to thinness, or the need for further surgery if the skin flaps are too thick or poorly placed.

Studies show that 20% to 70% of patients have positive margins, meaning cancer cells are found at the edge of the removed tissue, after breast conserving surgery. A 2016 study found that larger lesions requiring multiple needles for placement, a process called bracketing, upped the risk of positive margins 2 to 3 times. However, removing additional margins during surgery lowered the rate of positive margins in the final pathology report.

Poor cosmetic results is another surgical complication that could leave patients unhappy. To avoid this, oncoplastic techniques can be used during the first surgery or additional operation can be performed later.

Medical complications can also arise from hormonal therapy with Tamoxifen. These include uterine cancer, stroke, blood clot in the vein, and a blood clot in the lungs.

Side effects from radiation therapy include changes to skin and tissue such as firmness, reduction in size, discoloration and others. It can also lead to tiredness, cough, difficulty breathing, rib fractures, and, in rare cases, a rare type of cancer called angiosarcoma and damage to the network of nerves in the arm.

Types of complications:

- Surgical complications like infection, bruising, fluid-filled swelling, wound reopening, collapsed lung, death of skin flaps, need for further surgery

- Positive margins after surgery

- Poor cosmetic outcome

- Medical complications from hormone therapy

- Complications from radiation therapy

invasive ductal carcinoma (x10). The left side of the image shows a sheet of

cells with pleomorphic nuclei, arranged in tubules, infiltrating into the breast

stroma, consistent with invasive ductal carcinoma that originated from the

adjacent high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ on the right side of the image.

Preventing Breast Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

It’s important to understand that higher levels of extra estrogen in the body can elevate the risk of breast cancer. This knowledge can greatly help in educating patients. Changes in lifestyle and behavior, such as stopping the use of hormones after menopause and reducing alcohol consumption, can lower a woman’s chance of developing breast cancer.