recurrent. These lesions (with cranial vault involvement, soft-tissue scalp

swelling, and underlying intracranial mass) can mimic a meningioma.

What is Central Nervous System Lymphoma?

Lymphoma affecting the central nervous system, or the brain and spinal cord, is a rare yet severe type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. This includes primary lymphoma, which starts in the brain, and secondary lymphoma, derived from cancer spread from other body parts to the brain. Though known for being aggressive and having a poor prognosis, primary lymphoma of the central nervous system often reacts positively to treatments and could potentially be cured.

Different advanced treatments such as high-dose radiation coupled with stem cell transplants, alongside newer strategies like the drug ‘ibrutinib’, are contributing to the likelihood of better results. Primary lymphoma can affect any part of the central nervous system, including the eyes, the membrane covering the brain & spinal cord, the brain itself, and the spinal cord.

Historically, without treatment, the overall survival rate of primary central nervous system lymphoma was around 1.5 months, and even with treatment, the 5-year survival rate was about 30%. The form these lymphomas most commonly take is diffuse B-cell lymphoma, often localized within the brain but can occur elsewhere. The characteristics of the cancer and its location determine the symptoms, potential treatments, and outcome.

Patients with an aggressive form of systemic non-Hodgkin lymphoma have a 2% to 27% risk of the cancer spreading to the brain, with a typical survival rate of 2.2 months after diagnosis. Thankfully, new treatments such as high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy are now improving the survival rates for this type of lymphoma.

What Causes Central Nervous System Lymphoma?

Being immunodeficient, either naturally or due to a certain condition, greatly increases your risk for developing PCNSL, a kind of brain lymphoma. This particularly applies to those who have AIDS, as PCNSL is typically diagnosed when the person’s CD4 count (a type of white blood cell) is below 50 and the person is not on strong antiviral medication.

In addition, people who have had organ transplants can also develop this type of lymphoma. Up to 2% of people who have had a kidney transplant and up to 7% of people who have had a heart, lung or liver transplant can end up developing lymphoma in their central nervous system. This risk is especially high during the first year after a heart or lung transplant.

The Epstein-Barr virus, which is known to cause mononucleosis, is strongly linked to CNS lymphoma in patients who have weakened immune systems due to, for example, being on medication to suppress the immune system after an organ transplant. Similarly, every PCNSL case in people living with AIDS is also associated with the Epstein-Barr virus.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Central Nervous System Lymphoma

CNS lymphoma is becoming less common in people living with AIDS thanks to new medication. However, its occurrence is increasing in the elderly. It’s quite a rare condition in children. Annually, there are roughly 1700 cases of CNS lymphoma in the U.S., which equates to around 0.5 people in every 100,000. CNS lymphoma makes up 3% of all primary brain tumors and about 2% to 3% of all cases of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

People with a healthy immune system usually get diagnosed between the ages of 50 and 70, while those with weaker immune systems often get diagnosed in their 30s or 40s. Men are affected more than women, irrespective of their immunity. However, in patients who develop CNS lymphoma after an organ transplant, the chance of getting the disease is the same for both sexes. People with ataxia-telangiectasia and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, as well as other immune deficiencies, are also at risk.

Most CNS lymphoma cases (over 90%) are categorized as a type of cancer called ‘diffuse large B-cell lymphoma’. Others may be T-cell and Burkitt lymphomas or lower-grade lymphoproliferative conditions. Within the brain, the frontal lobe and the basal ganglia are most commonly affected. Less commonly, the brainstem, cerebellum, and spinal cord might be affected. Most patients with a healthy immune system have a single brain tumor, but multiple tumors occur in 20% to 40% of cases.

- About 25% of CNS lymphoma patients also develop a type of eye cancer called intraocular lymphoma

- Intraocular lymphoma can eventually spreads to the CNS in over 80% of the cases.

- Up to 20% of cases might also involve the brain fluid and the orbit.

- Intraocular lymphoma is mostly found in the fluid of the eye and the retina.

- CNS lymphoma rarely spreads outside of the central nervous system.

- About 40% of all systemic lymphomas (cancer that affects the entire body) originate in or near the central nervous system, including the paranasal sinuses and the locations mentioned above.

- Secondary CNS lymphoma mostly affects the dura and leptomeninges (layers that cover the brain).

- Leptomeningeal metastases (spread of cancer to the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord) occur in 4% to 11% of patients with systemic lymphoma.

primary lymphoma, referring to isolated involvement of the craniospinal axis in

the absence of primary tumor elsewhere in the body.

Signs and Symptoms of Central Nervous System Lymphoma

Central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma can have different symptoms depending on whether it’s primary or secondary. It’s crucial to be vigilant because the symptoms can vary greatly. A lot of patients with primary CNS lymphoma experience focal neurologic deficits, meaning that they might have specific neurological problems due to direct nerve invasion or involvement of the meninges (the protective layers covering the brain and spinal cord). However, more general symptoms can occur too, such as cognitive decline or behavioral disruption, especially in older individuals.

If the symptoms are focal, brain scans are usually done quickly, which helps in making a rapid diagnosis. But if the symptoms are general (like cognitive or behavioral disturbances), it can lead to delays in diagnosis that could last weeks to months. Unlike systemic lymphoma, which affects the entire body, primary CNS lymphoma rarely presents with systemic symptoms like fever, night sweats, or weight loss. Peripheral nerve symptoms indicate that the meninges or nerves are directly invaded. Even though it can also be asymptomatic, involvement of the meninges can result in cranial neuropathies or symptoms localized to the lower end of the spinal cord like urinary retention or saddle anesthesia. Direct nerve invasion can result in painful radiculopathy, which is nerve root pain. Depending on where the tumor is located, patients may also experience one-sided weakness (hemiparesis), loss of sense of touch (hemisensory loss), and unsteadiness (ataxia). Up to a third of patients with primary CNS lymphoma may have general signs of increased pressure within the brain, such as nausea, vomiting, and headache. While outright visual problems are rare, up to 25% of patients can have eye involvement.

Here is a summary of the potential symptoms in central nervous system lymphoma:

- Neurologic deficits due to nerve invasion or meningeal involvement,

- Cognitive decline or behavior disruption,

- Delays in diagnosis with general presentations,

- Peripheral nerve symptoms suggesting meningeal or nerve invasion,

- Symptoms localized to the lower end of the spinal cord like urinary retention or saddle anesthesia,

- Painful radiculopathy due to direct nerve invasion,

- Hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, or ataxia depending on the tumor location,

- General signs of increased intracranial pressure such as nausea, vomiting, and headache,

- Rare outright visual problems but potential eye involvement in up to 25% of patients.

with gadolinium contrast is the recommended first test in the diagnostic workup

for patients with suspected primary central nervous lymphoma.

Testing for Central Nervous System Lymphoma

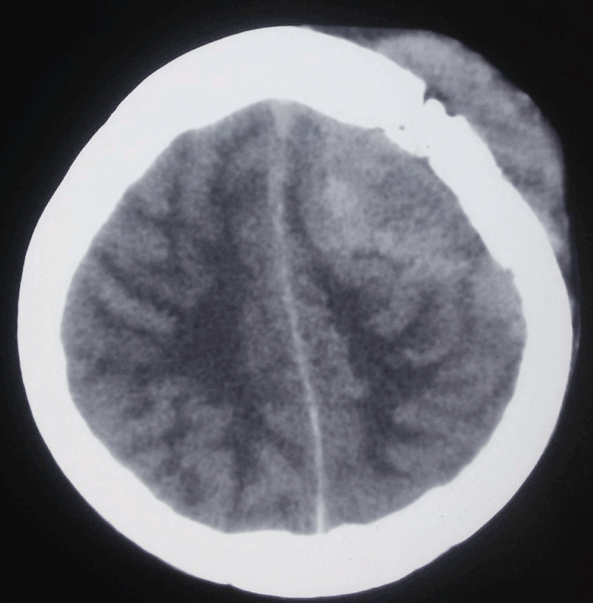

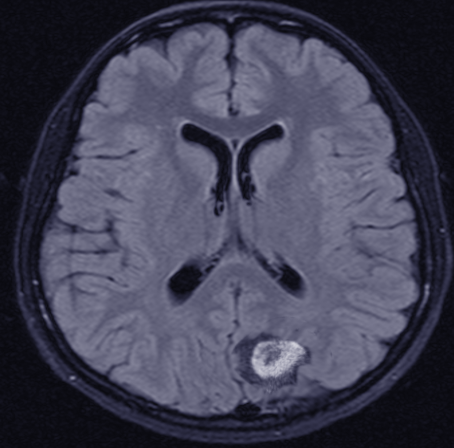

If doctors suspect a patient has Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma (PCNSL), a type of cancer in the brain, the first recommended test is a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan of the brain with a special contrast dye. This helps highlight any unusual areas.

Common features of PCNSL on an MRI include:

– Lesions often seen centrally within the white matter and regions around the brain ventricles.

– These lesions appear of normal or lower brightness on certain types of MRI images (T1-weighted), and normal or higher intensity on different kinds of MRI images (T2-weighted).

– There’s often swelling around the lesions but this is less pronounced than in other forms of brain tumors or cancer spread.

Lesions are typically solitary, with even enhancement, but in about 20% to 40% of cases can be multiple, sometimes forming a ring-like pattern.

People whose immune systems are weak may present with multiple necrotic (dead tissue) lesions in an irregular ring-enhancing pattern in about 30% to 80% of cases after contrast is added.

In addition to the standard MRI procedures, other types of sequences and imaging strategies can be helpful. For instance, doctors can use diffusion-weighted sequencing to observe the restricted movement of water molecules due to the dense structure of PCNSL cells. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS), on the other hand, can spot PCNSL based on profiles of different chemicals found in the brain.

One challenge though, MRI has low sensitivity for catching primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (a kind of lymphoma affecting the eye), requiring special techniques to detect any tiny enhancing lesions on the macula or uvea (parts of the eye).

Besides MRI scans, Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan is used to tell the difference between PCNSL and glioma (another type of brain tumor) and infections. PCNSLs are often more active metabolically than gliomas and may show up more notably on a PET scan.

When other tests might not be conclusive, a brain biopsy might be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Here, a small piece of brain tissue is removed for study under the microscope. This method can confirm PCNSL in over 91% of cases.

Lastly, a set of tests have been recommended for a thorough diagnosis of PCNSL, including comprehensive MRI, lumbar puncture, eye examination, ultrasonography in older men, whole body PET scan and bone marrow biopsy, HIV and hepatitis tests, evaluation of the individual’s overall health (performance status), and testing levels of certain substances in the body which might indicate disease presence.

Treatment Options for Central Nervous System Lymphoma

Treatment for PCNSL should start as quickly as possible after diagnosis. This usually involves an initial phase of chemotherapy (called induction) to reduce the tumor size, followed by a consolidation phase to target lingering microscopic cells. Consolidation aims to completely rid the body of the disease, or at least provide a long-term remission.

It’s important to note that corticosteroids, a type of medication, should not be used before a diagnostic biopsy. They can interfere with the biopsy results, making diagnosis more difficult or even leading to “vanishing” tumors in up to half of the cases. Additionally, several other conditions including glioblastoma and multiple sclerosis also respond positively to steroids, so their use doesn’t necessarily mean the patient has PCNSL. Patients prescribed corticosteroids should have frequent medical check-ups and scans to monitor the possible re-growth of the tumor.

Historically, the usual treatment for new cases of PCNSL was full brain radiation therapy (WBRT). However, this often resulted in early relapse and various side effects linked to radiation. Moreover, patients typically survived for only 12 to 18 months with WBRT alone. It’s also important to mention that complete surgical removal is typically not an option for PCNSL due to its diffuse nature.

The first part of the current treatment strategy involves the use of potent chemotherapy drugs, with following consolidation therapy aiming to get rid of any remaining disease to prolong survival. It typically starts with a high dose of methotrexate, mixed with other chemotherapy drugs. However, the best methotrexate-based therapy and the optimal dose of methotrexate haven’t been established yet. Because methotrexate doesn’t penetrate well into the central nervous system, high doses are usually necessary.

As for consolidation therapy, some of the options available include high or low-dose radiation, and intensive chemotherapy with various agents. Research has shown that excluding WBRT from consolidation therapy did not compromise survival and resulted in better neurological outcomes for patients. Other options include stem cell transplant, although it’s not suitable for everyone due to its harshness.

Despite these treatments, over half of the patients with PCNSL experience a relapse, typically within 5 years but it can occur as much as 10 years later. There are several potential treatments upon relapse, including additional methotrexate and other drugs, stem cell transplant or WBRT if it wasn’t used previously. Several new potential treatments are also currently being investigated.

It’s critical to monitor patients closely after treatment to detect any signs of relapse. This should be done every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 3 to 5 years, and finally annually until the patient reaches the 10-year mark. Methods of monitoring can include medical history checks, overall and neurological exams, brain scans, ocular exams, and potentially a lumbar puncture.

What else can Central Nervous System Lymphoma be?

The potential causes of this condition are varied. They are guided by the symptoms the patient presents with.

- If the disease affects the substance of an organ (intraparenchymal disease), it might be confused with other tumors of the brain and nervous system, such as aggressive cancers (high-grade gliomas) and cancers that have spread from another part of the body (metastatic lesions).

- When a particular type of scan (an MRI) shows certain patterns, a stroke (cerebral infarct) must be considered as well as other diseases that cause inflammation and damage to the protective insulation surrounding the nerve fibers in the brain (tumefactive demyelination) or other causes of inflammation.

- If a patient has a weakened immune system and the scan shows areas of enhancement, serious infections, such as toxoplasmosis and fungal abscesses, need to be ruled out.

Tolosa Hunt syndrome, a condition causing intense eye pain due to inflammation in the back of the eye, can look a lot like this condition clinically and on imaging studies. Like in this condition, symptoms in Tolosa Hunt syndrome improve with steroids.

What to expect with Central Nervous System Lymphoma

Aggressive treatment is usually used for CNS lymphoma. Even patients with severe symptoms or health complications due to the disease can benefit from chemotherapy and radiation treatment because these tumors respond very well to them. Studies have shown that around 30% of patients might live more than five years, and around 20% live past ten years.

Treatments that only include radiation extend the patient’s life for about 12-18 months and increase their chances of surviving for five years to around 18-35%. However, this is associated with a high risk of damage to the nervous system.

The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) found that radiation leads to a median survival of around 12 to 18 months and a 5-year survival rate of only 3% to 4%. It also noted no additional survival benefit from standard NHL chemotherapy regimen (consisting of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone) followed by radiation treatment, and it had significant side-effects related to chemotherapy.

When a drug called HD-MTX was used together with other treatments, the median survival increased to 40 months, and the 5-year survival rates rose by almost 22%. Patients who receive brain radiation are susceptible to leukoencephalopathy, a condition that can cause dementia, gait irregularities, and incontinence, particularly in older patients. Brain changes seen in MRI scans typically accompany this condition. It’s thought to be caused by the loss of myelin (a substance that protects nerve fibers) and nerve cells in the hippocampus (a part of the brain important for memory). For these reasons, brain radiation is now only considered in patients who can’t have chemotherapy or as a secondary therapy in resistant or relapsed cases.

The current focus is on the long-term effects of consolidation therapies. In combination with stem cell transplantation, high-dose chemotherapy could highly control the disease. A recent study from the PRECIS trial found that autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), where the patient’s own stem cells are used, gives an average of 67% event-free survival rate over eight years, which was significantly better compared to 39% in those who had brain radiation. Patients who received ASCT also maintained better cognitive abilities and balance.

Despite advances in treatment methods, the survival rates are still challenging, with less than 40% of patients surviving for more than five years. Some of the reasons include limited drug access to the brain due to the blood-brain barrier, the difficulty of intense treatment regimens for older adults, and unknown inherent resistances to chemotherapy in tumor cells.

Two well-known methods, the International Extra-nodal Lymphoma Study Group and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center model, help predict the patient’s survival; they consider factors such as age, health status, lactate dehydrogenase levels, CSF protein concentration, and whether deep brain structures are affected.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Central Nervous System Lymphoma

Whole-Brain Radiation Therapy (WBRT) can have several complications, particularly in patients over 60 years old. These complications commonly include difficulties walking, memory loss, and loss of bladder control. Some people also develop post-traumatic stress disorder after receiving this therapy. Other health risks are associated with WBRT as well. For instance, people who have survived long-term CNS lymphoma can have an increased chance of developing another type of cancer, especially among younger individuals. In addition, if a patient with secondary CNS lymphoma receives radiation therapy to the chest, they could have a higher risk for heart disease.

Furthermore, some medications used in treatment can pose other health risks. For instance, a type of medication called anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin, can potentially harm the heart. Another drug, rituximab, is associated with a higher chance of developing a condition called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Patients with CNS lymphoma who received a transplant face the risk of their new organ failing, especially if their immunosuppressant medication is reduced or stopped in order to boost their immune function.

The common complications include:

- Difficulty walking

- Memory loss

- Loss of bladder control

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

- Increased risk of heart disease (from radiation therapy to the chest)

- Potential heart damage (from anthracyclines)

- Increased risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (from rituximab)

- Possible organ failure (in transplant patients with CNS lymphoma)

Preventing Central Nervous System Lymphoma

It’s important for patients to understand their disease and what to avoid during treatment. When taken in high doses, a drug called MTX can build up in the kidney’s tubes and cause damage. This risk becomes higher when the urine is acidic and when the body is dehydrated, so it’s very important to stay properly hydrated. There are certain drugs, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, penicillin, probenecid, phenytoin, ciprofloxacin, proton pump inhibitors, and levetiracetam, that can affect how the kidneys remove MTX from the body, and these should be avoided if possible.