What is Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children?

After the first case of pediatric anti-NMDAR encephalitis was noted in China in 2010, this illness is now commonly identified among children. It currently ranks as the second most common reason for acute demyelinating encephalitis, just behind mixed disturbance encephalitis, and has now exceeded all virus-related causes for encephalitis.

What Causes Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children?

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis is a brain inflammation condition caused by the immune system wrongly attacking specific parts of the brain – the GluN1 subunit 2B (NR2B) and NMDA subunit 2A (NR2A) parts of the NDMA receptor in the hippocampus region. At first, it was thought this condition was mostly linked to a form of ovarian cancer called a teratoma. However, studies showed this only to be the case for 31% of children under 18 years old and 9% of children under 14.

Another clear link has been found with a type of brain inflammation caused by the herpes simplex virus. In a study of 99 patients, 27% (and 64% of these who had NMDA receptor antibodies) developed autoimmune encephalitis 2-16 weeks after having herpes simplex brain inflammation. There’s also some evidence suggesting a link to two specific genes (HLA-I allele B*07:02 and HLA-II allele DRB1*16:02), but more research is needed to confirm this.

In a project in California, it was discovered that the anti-NMDAR antibodies were made in children after an infection with mycoplasma bacteria. This suggests that the brain inflammation might be the body’s unintended response to certain infections, with the immune system wrongly creating antibodies that attack parts of the brain. This discovery highlights the importance of checking for signs of autoimmune encephalitis in cases of unusual brain inflammation caused by a virus.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis, which was only identified 13 years ago, is a rare condition, with only about 1.5 cases per year for every million people. Still, there have already been over 1000 cases reported. People from all different age groups and of all genders can be affected, although it’s more common in females, who make up 75% of cases.

- Anti-NMDAR encephalitis was identified 13 years ago.

- It’s a rare disease with about 1.5 cases per million people each year.

- Over 1000 cases have been documented so far.

- It can affect people of all ages and genders.

- However, it’s more common in females who make up 75% of cases.

Research has found that non-White individuals, particularly those with ovarian teratomas, are at a higher risk of getting anti-NMDAR encephalitis. This has been documented in literature and has been seen in individuals as young as three months old.

Signs and Symptoms of Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis is a complex condition that generally goes through four distinct stages.

- Prodromal phase: This phase is like the onset of a typical infection with symptoms such as fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and symptoms that are similar to a common cold.

- Illness phase: During this stage, there may be changes visible on an MRI scan or in blood tests, but no clear change in symptoms. This is significantly different from other types of encephalitis where there is significant loss of neurons.

- Psychiatric phase: This phase, which can last one to two weeks, is often marked by changes in behavior such as becoming irritable, having tantrums, irregular sleep patterns, hyperactivity, and even falling into a coma.

- Neurological phase: This phase can last weeks to months and is characterized by seizures, speech changes, difficulty with movement coordination, and even difficulty in breathing, requiring intensive care. Instances of motor dysfunction can evolve into uncontrolled movements especially in the face. Young children may also experience balance problems or lose the ability to walk.

- Recovery phase: This stage is typically a reversal of symptoms, and cognitive and psychiatric functions are often the last to improve. With appropriate treatment and medical care, this stage can begin a few months after the start of the illness. Images from MRI and other tests may show minimal inflammation at this stage and antibodies may still be found even after a full recovery.

- Late phase: At this point, most patients are generally fully recovered with their cognitive and behavioral health back to normal by the time they leave the hospital.

Testing for Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children

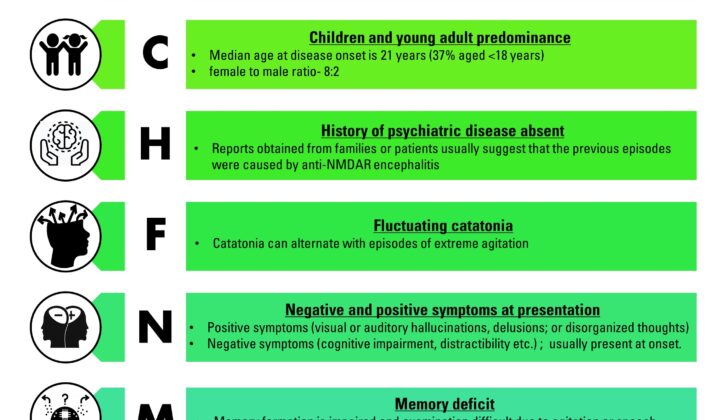

Every child should be tested for the herpes simplex virus (HSV) and other viruses, with the choice of tests varying based on the time of year and location. Certain telltale signs can aid in diagnosing anti-NMDAR encephalitis, as shown in figure 1. To confirm the diagnosis, it’s necessary to prove the presence of IgG antibodies against the GluN1 subunit of NMDAR in a blood or fluid sample from the spine (also known as CSF sample). This CSF sample can also show signs of more white blood cells than usual (lymphocytic pleocytosis), elevated protein levels, and specific oligoclonal bands.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain can show increased signal intensities in certain areas of the brain and spinal cord, including the hippocampus, frontal cortex, medial temporal lobe, cerebellar cortex, spinal cord, and medulla oblongata. However, these signs were only visible in 30% of patients in one particular study. It’s most common to find these lesions in the hippocampus, and their presence here is often a sign of a worse prognosis.

An Electroencephalography (EEG), a test that measures brain activity, usually shows a slow and irregular pattern in both the delta and theta range as well as overlaid seizures. This is seen in about 90% of patients at some point during the disease.

Treatment Options for Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children

Children who experience symptoms like irregular heartbeat, over-breathing, or severe stress due to a nervous system disorder can have complications. These kids should be cared for in an intensive care unit (ICU). The first line of treatment often includes surgery to remove tumors (if any), immune therapy (via steroids, plasma exchanges or intravenous immunoglobulins) and supportive care. If the child doesn’t have a tumor, they might need further treatment, including drugs like rituximab or cyclophosphamide. Folks without a tumor generally have a higher relapse rate, so it’s normally suggested that they continue immune system treatment for about a year with medicines such as mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine.

Sleep issues can be treated with specific medicines like clonidine, trazodone, and benzodiazepines. Other medications can help with severe agitation. Methotrimeprazine or dexmedetomidine can be especially helpful for children who are overly agitated. If a patient has catatonic symptoms, they’re often given a daily dose of lorazepam (up to 20-30 milligrams). Electroconvulsive therapy can be a treatment option when other treatments have failed.

Psychosis and behavioral issues are usually handled with typical or atypical antipsychotics. Quetiapine is often used for treating psychosis. Valproate is great at stabilizing moods and also helps prevent seizures. Gabapentin and lithium can also be used for mood regulation.

If none of these treatments work, doctors can consider mechanical ventilation and drug infusions with medication such as ketamine or propofol. Children under 5 have a higher risk with propofol, so they need careful monitoring if receiving this treatment for longer than 24 hours. Reducing noise can keep children from becoming agitated. If steroids are used as part of the treatment, muscle relaxants should be avoided to prevent muscle weakness.

Rapid heartbeat is a common symptom for kids with this condition. Slowed heart rate can be linked to seizures, so constant monitoring is important. Drugs such as glycopyrrolate or theophylline have been shown to prevent severe slowing of the heart rate. Issues with automatic body functions can look like fluctuating temperature and blood pressure. Movement disorders can get worse when a child has a fever, so maintaining a steady body temperature is important.

During the third week of treatment, adding breathing and feeding tubes can improve patient safety, and allows less sedation to be used. Once possible, starting a full rehabilitation program is crucial. This would include physical therapy, speech therapy, and occupational therapy.

What else can Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children be?

If a doctor suspects a specific disorder that affects brain function, they might turn to either a neurologist (brain specialist) or a psychiatrist (mental health specialist). Many different conditions could potentially be at play:

- Substance misuse

- Conditions that happen after an infection, such as a virus or bacteria

- An autism-like condition that temporarily appears in kids during serious all-over brain sickness

- Sudden widespread inflammation in the brain and spinal cord

- A kind of temporary brain inflammation that affects the emotions and memory

- Brief all-over brain inflammation that shows up without a herpes virus infection

- A kind of all-over brain and spinal cord inflammation (ADEM) that comes on suddenly

- Genetic conditions that disrupt the body’s normal chemical reactions

- Damage due to harmful substances in the environment or an overdose of medication

- Conditions affecting the joints, muscles, and connective tissues such as lupus that also has mental health symptoms

- Mental health disorders such as schizophrenia

In each case, the doctor needs to tailor the investigation based on the individual’s unique situation and symptoms.

What to expect with Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children

Research shows that 75% of patients with a condition called NMDAR encephalitis recover completely or with only mild remaining symptoms. However, the remaining 25% may face serious health problems related to the central nervous system or can even die. Studies have found that there’s a 12% to 24% chance of the illness returning at some point in a person’s life.

In a study done on 382 patients, ranging in age from 1 to 85, a scoring system was created to predict the impact of Anti-NMDAR encephalitis on a patient’s life one year after diagnosis. This scoring system, known as the NEOS score, allocates a point to five different factors. These factors include needing intensive care, delay in treatment for more than four weeks, lack of improvement within four weeks, having abnormal MRI results, and having more than 20 white blood cells in a specific amount of cerebrospinal fluid (the fluid around your brain and spinal cord).

Patients with a score of zero or one have a low chance (3%) of their health being significantly impacted after a year. On the other hand, those with a high score of four or five have a 69% chance of experiencing serious health problems one year after diagnosis. Doctors and healthcare providers find this one-year outlook vital when discussing the likely outcome with the patient’s family.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children

Experts suggest that recognizing and treating the disease early on can cause less harm to the hippocampus, an important part of the brain. However, we still don’t know the best timeframe between when symptoms start and the beginning of treatment. Research by Dalmau indicates that recovery is a multi-stage process that reverses the order in which symptoms appeared.

Preventing Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis in Children

In order to avoid misdiagnosing people with an illness called anti-NMDAR encephalitis, doctors need to carefully examine the symptoms and identify specific antibodies in a fluid called CSF. There’s no specific sign doctors can use to forecast how this illness will progress. So, it’s crucial to share knowledge about this condition to improve patient care and recovery.