What is Branchial Cleft Cyst?

Branchial cleft cysts are birth defects that happen from the first to fourth ‘pharyngeal clefts,’ which are essentially grooves in the neck and face area that form during early stages of a baby’s development in the womb. The most common type comes from the second cleft, while cysts from the first, third, and fourth clefts are less common.

Even though these defects are present at birth, they might not show any signs or cause any issues until later in life. Most of the time, these defects show up in childhood as a small hole in the skin. However, they can also appear as cysts or lumps in the neck, which can sometimes be mistaken for neck abscesses (pockets of pus caused by an infection).

Branchial cleft anomalies can come in one of three forms: as cysts, sinuses, or connections called ‘fistulae.’ Cysts have a skin-like lining without any openings to the outside, so they might not show any symptoms and might only be found by chance. Some of these cysts might not show up until adulthood.

Sinus tracts are another form that can connect either with the skin through a visible hole or with the areas of the throat or voice box, where the opening may only be seen with an endoscope (a device used to view the inside of the body). The last type, fistulae, are actual connections linking the throat or voice box with the skin.

What Causes Branchial Cleft Cyst?

Branchial cleft anomalies are issues that occur due to incomplete development of branchial cleft structures. These issues occur early in pregnancy, during the fourth week, when certain cells, known as neural crest cells, move into what will become the head and neck. Here, they create 6 pairs of branchial (or pharyngeal) arches.

These arches, which are separated by parts known as clefts on the outer layer (ectoderm) and pouches on the inner layer (endoderm), are then covered by a different type of cell layer or a mesoderm layer. Normally, there are 5 branchial arches, resulting in four pharyngeal clefts.

During development, the second arch grows towards the tail-end and then covers the third and fourth arches. These buried clefts become cavities lined by the ectoderm layer. Normally, by the seventh week of pregnancy, these cavities completely disappear (involute). But, if they do not disappear completely or disappear partially, they will form pathologies such as cysts (a fluid-filled sac), sinuses (an abnormal cavity or channel in the body), or fistulae (an abnormal connection between two body parts) in predictable locations according to their branchial cleft of origin.

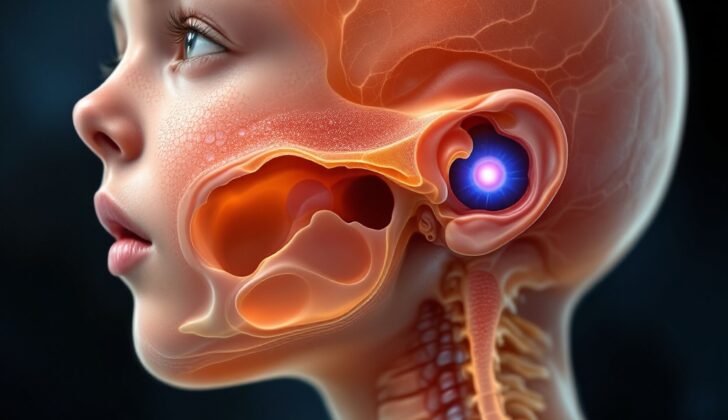

First Branchial Cleft Cyst is one such anomaly that is further split into two types (Work type I and Work type II), which can appear as masses near the ear or the jawline.

Second Branchial Cleft Cyst is the most common branchial cleft cyst, which is usually found near the sternocleidomastoid (a muscle located in the neck) on the neck skin.

Third Branchial Cleft Cyst makes around 2-8% of all branchial cleft anomalies. When present, they can be found over the middle to the lower third of the anterior sternocleidomastoid.

The fourth and last one, Fourth Branchial Cleft Cyst, is extremely rare and is responsible for approximately 1% of all branchial cleft anomalies. Not much is known about them because of their rarity.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Branchial Cleft Cyst

Branchial cleft anomalies are common in the United States, but we don’t know exactly how often they happen. This is because there are many different types of these anomalies, and they can present in different ways, making it hard to record accurately. They happen in people of all ethnic backgrounds, and neither men nor women are more likely to have them. Most branchial cleft anomalies come from the second pouch, while the first, third, and fourth pouches are less common. Also, about 10% of people with these anomalies have them on both sides. They usually show up in the first decade of a person’s life, but if there is no external sign of the anomaly, it might not be noticed until adulthood.

Signs and Symptoms of Branchial Cleft Cyst

Branchial cleft cysts often don’t cause any noticeable symptoms, but sometimes they can be painful or become larger, especially if they get infected. This frequently happens during an upper respiratory tract infection. If infected, pus can drain from the cyst to the skin or throat. In some serious cases, patients can experience difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, or wheezing due to pressure on the upper airway. These fluid-filled sacs usually become noticeable in the teenage years and can be found underneath the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which is the large muscle on the side of your neck. During an upper respiratory infection, the cyst size may change in up to a quarter of cases.

Depending on where the branchial cleft cyst is located, the physical exam might yield different results:

- A first branchial cleft cyst might feel smooth or squishy and is typically located between the outer part of the ear and the side of the neck. It is often associated with the parotid gland (a major salivary gland) and the facial nerve, and it could be connected to the middle or outer ear. Therefore, an examination of the ear is very important for these patients.

- Second branchial cleft cysts are usually found at the lower front border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. They can be tender when infected and in severe cases, might interfere with breathing. They might also be near the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves (which control swallowing and tongue movements) as well as major blood vessels. If the cyst is connected to a sinus tract, there might be a mucousy or pus-like discharge on the skin or into the throat.

- Third and fourth branchial cleft cysts are very uncommon. They are normally found on the left side of the neck or near the collarbone. They usually feel firm or seem like an inflamed cyst draining to the piriformis sinus (a depression in the throat) or the neck skin. They are more likely to be discovered when infected and might have been repeatedly drained due to incorrect diagnosis and ongoing recurrence.

Testing for Branchial Cleft Cyst

For evaluation, there’s no particular lab test required.

Regarding imaging studies, there are several methods your doctor may use if they suspect this condition. If there’s a small tunnel connecting tissue in your body (known as a sinus tract), a special X-ray using dye, called a sinogram, might be pursued. This test allows your doctor to see the structure and size of the cyst more clearly.

Ultrasound could also be used. This test uses sound waves to create images of the cyst and gives your doctor more information about its nature.

In some cases, your doctor might opt to use a contrast-enhanced CT scan, which provides a clear image of a fluid-filled pouch (cyst) and surrounding tissues in the neck. This test involves the use of a special dye to make the cyst stand out in the images.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide even more detailed images and can be used if your doctor needs a more precise view of the cyst and its environment.

Finally, a method called fine-needle aspiration can be helpful in distinguishing between a branchial cleft cyst – a cyst that develops on the side of the neck or just below the jawbone – and a cancerous growth. This process involves using a thin needle to take a sample of the cyst contents for further analysis.

Treatment Options for Branchial Cleft Cyst

When it comes to treating a branchial cleft cyst, a growth typically present at birth, doctors usually opt for removal via surgery. This is done to prevent potential complications such as infection, further growth, or a very small chance of turning into cancer. However, unless the cyst is causing breathing problems or has turned into a large abscess, there’s no rush to remove it. The surgery can usually be postponed until the child is 3 to 6 months old or after an ongoing infection has been treated.

In cases where the cyst is causing significant issues such as trouble breathing or a large abscess, immediate surgery may be necessary. Even then, most doctors prefer a combination of antibiotics and draining the fluid from the cyst as opposed to making a cut and draining it (incision and drainage). The reason for this is that incision and drainage might change the normal layers of tissues and make the surgical removal of the cyst more complicated.

The surgical procedure for removing the cyst is planned in a way that results in the smallest possible scar, ideally placed within a natural skin crease. If there’s a channel or hole (fistula or sinus) connected to the cyst, doctors use a special technique to ensure its complete removal and reduce the chance of the cyst coming back. They use a device to probe the hole and might use a dye for easy identification. Precision is crucial as the channel can be thin-walled. If the channel is long, a second small incision is made in a nearby skin crease to facilitate the procedure. In certain types of branchial cleft cysts, which have close association with facial nerves, a special approach is adopted to avoid any nerve damage. In some cases, they also use imaging techniques (fistulograms) to guide the surgery.

If, for any reason, the person can’t undergo surgery, another method that involves injecting a type of alcohol (ethanol) into the cyst to shrink it has been used. This, however, is usually not the first choice of treatment.

In case of third and fourth branchial cleft cysts, that develop lower down in the neck and near the windpipe, the treatment generally involves a specific surgical approach that protects the nerves controlling voice box (recurrent laryngeal nerves). Sometimes, part of the thyroid gland may also have to be removed to ensure complete removal of the cyst. Prior to performing this part of the surgery, a visual examination of the voice box and windpipe is performed to confirm the diagnosis and guide the surgical procedure.

What else can Branchial Cleft Cyst be?

Other conditions that physicians might consider when evaluating a patient could include:

- Swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy)

- Blood vessel tumors (hemangiomas)

- A kind of tumor found near the carotid artery (carotid body tumor)

- A fluid-filled sac in the neck (cystic hygroma)

- Thyroid or salivary tissue in an unusual location (ectopic thyroid/salivary tissue)

- Tumors/malformations in the blood vessels (vascular neoplasm/malformation)

- Cysts that are a leftover from the thyroid’s development (thyroglossal duct cysts)

- An infection caused by a cat scratch (cat scratch disease)

- Infections caused by a type of bacteria called mycobacteria, but which don’t behave like typical mycobacterial infections (atypical mycobacterial infections)

- A kind of squamous cell carcinoma that appears as a cyst (cystic squamous cell carcinoma)

What to expect with Branchial Cleft Cyst

It’s important for patients and their families to understand that branchial cleft cysts, which are generally non-cancerous, can be effectively treated. After treatment, patients usually recover without experiencing any complications or the cyst returning.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Branchial Cleft Cyst

Branchial cleft cysts are growths present from birth which can be removed surgically. After removal, it isn’t very common for them to return, with an average comeback risk of about 3%. But in cases where there has previously been surgery or recurrent infection, the risk of the cysts returning could rise to as much as 20%.

General facts about branchial cleft cysts after surgery:

- Average risk of recurrence: 3%

- Risk of recurrence after previous surgery or recurrent infection: Up to 20%

Preventing Branchial Cleft Cyst

Branchial cleft anomalies are birth defects, and at present, there are no known ways to prevent them. Both patients and doctors should be aware of the possible signs and symptoms that might lead to an early diagnosis of these conditions. Understanding these signs could potentially lower the cost of the patient’s care. This is because it would prevent future doctor appointments, repeated use of antibiotics, and the need for further diagnostic tests.