What is Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip?

Developmental dysplasia of the hip is a condition where the hip joint doesn’t form correctly in infants or young children. This problem can range from minor instability in the hip to a complete dislocation. In this condition, several hip problems can be present including looseness, abnormal growth of the hip socket, partial dislocation, or completely out-of-place joint. Most of the time, kids with this condition don’t have any other health issues. Previously, this condition was referred to as “congenital dislocation of the hip”, but since not every baby has it at birth, it’s now called “developmental.”

The reason why this happens is still not completely understood. It seems to involve a mix of genetics, environmental factors, and issues with how the body forms. Some genetic markers are more common in families with this hip problem.

While some forms of developmental dysplasia of the hip can get better on their own, some children will need early treatment to avoid future problems as adults. Health professionals need to identify what is causing the hip problem to offer the right care and to know what to expect for the child’s future.

To diagnose developmental dysplasia of the hip, doctors observe the baby and use imaging technology. Examining the patient involves tests like the Ortolani test and Barlow maneuver, looking at the range of hip movement, and examining any other concerning physical traits. If any problems are spotted, additional tests like an x-ray or ultrasound may be needed depending on the child’s age. Detecting and treating developmental dysplasia of the hip early can help prevent complications later in life, such as ongoing dislocation and early onset of arthritis in the hip.

Treatment can vary according to the severity and the child’s age. Some patients may only need less intensive methods like changing the types of activities they do, physical therapy, and the use of splints. In more severe cases, surgery may become necessary. There’s no scientific consensus on which surgical approach is best, so the treatment depends on the judgment of the surgeon and the individual patient’s situation.

What Causes Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip?

Certain factors can increase the chance of a child developing hip abnormalities, a condition often referred to as “developmental dysplasia of the hip”. Doctors use these as signs to determine if a child may be at risk and needs screening.

Girls are more likely to develop this condition than boys, about four times more commonly. This is possibly due to the laxity or looseness in the ligaments caused by hormones received from the mother.

If a baby is in the breech position during the last three months of pregnancy (meaning the baby’s buttocks or feet are positioned to come out first), this increases the risk of hip dysplasia significantly. Some procedures that alter the baby’s position or proceed with early delivery may reduce this risk.

Family history also plays a role, especially in Asian populations. Certain genes like COL2A1, DKK1, HOXB9, HOXD9, and WISP3 have been linked to this condition. Also, if a family member has had hip dysplasia, there’s an estimated 6% chances of recurrence in the family.

The way a baby is swaddled can also affect the risk. If the baby’s legs are wrapped straight down and together, it can increase the chance of hip dysplasia. Groups like the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA) recommend swaddling that allows the hip to move, especially in communities where hip dysplasia is more common.

Physical restriction within the womb, such as large-sized babies, low amniotic fluid, or multiple babies, can also increase the risk of hip dysplasia. Babies that are overdue are at a greater risk, but premature babies, interestingly, are not.

All these factors serve as guidelines to decide whether a baby needs to undergo hip screening to prevent potential complications and manage the situation optimally.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Developmental dysplasia of the hip is a condition that occurs in around 10 out of every 1000 babies born in the UK and US. At birth, 1 in 1000 babies have a dislocated hip due to this condition. There’s a significantly higher number of cases reported in Native American populations – more than 10 times higher, in fact. On the other hand, this condition is rarely found in African individuals. That’s why the number of cases tends to vary, depending on when it’s diagnosed, the race of the individual, and how diagnosis was carried out.

This condition can range from mild hip instability, which clears up on its own, to severe dislocation, which needs surgery. An interesting study showed a high number (69.5 out of 1000 live births) of cases diagnosed through ultrasound. But the good news is that most of these cases got better by themselves within about 6 to 8 weeks. After that, only 4.8 out of every 1000 individuals needed treatment for the hip condition. The researchers didn’t find any new cases when the children turned 1.

Contact with the mother’s spine, because of how the baby is positioned in the womb, often affects one hip more than the other. In fact, this is seen in 63% of cases. Due to this, the left hip is affected 64% of the time. This is because the most common position for a baby in the womb presses the left hip against the mother’s lower back and hip joint, leading to more pressure and potential restriction on the left hip joint as the baby develops.

Signs and Symptoms of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Developmental dysplasia of the hip can present in various ways depending on the ages. In infants, it may show up as mild hip instability and limited movement of the leg away from the body. Toddlers with this condition may walk unevenly. Teenagers may experience hip pain, whereas adults might develop osteoarthritis. Leading health organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), POSNA, and the Canadian Task Force recommend screening newborns for this condition.

Newborn Screening

Screening of newborns is important, especially for those with risk factors. Doctors typically use the Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers to check for hip instability or dislocation. Both maneuvers involve the baby lying on their back and the hip being moved in different ways. If a jerk or clunk is felt during these tests, it could indicate a dislocated hip.

- Ortolani maneuver: The baby’s hip is bent at a 90-degree angle and kept in a neutral rotation. Then, while applying some pressure, the hip is gently moved away from the body.

- Barlow maneuver: Starting in the same position as the Ortolani maneuver, pressure is applied towards the backside of the hip, and the hip is brought towards the body gently.

These maneuvers are quite accurate, with an 87% to 97% success rate in identifying such developmental hip issues at the hands of experienced practitioners. However, it’s important to note that asymmetry in hip position or differences in the number of wrinkles on the buttocks could suggest hip dysplasia but can also be present in 27% of infants without the condition. The Galeazzi sign, an examination comparing knee height while the hips and knees are flexed with feet on the table, can also be a valuable screening tool.

Postneonatal Screening

For older infants and toddlers, restricted hip movement might indicate developmental hip dysplasia. This is often characterized by less than 75-degree outward movement of the hip or more than 30-degree inward movement past the body’s midline. An uneven gait, a pronounced curve in the lower spine, toe walking, differences between leg lengths, and early hip osteoarthritis can also suggest the presence of hip dysplasia.

- Klisic test: In this test, two fingers are positioned on the prominent parts of the hip. On a healthy hip, an imaginary line between these two fingers will point at or above the belly button. On a dislocated hip, the line will point below the belly button.

Testing for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Several organizations, including POSNA, the Canadian Task Force on DDH, the AAOS, and the AAP, suggest regular check-ups for infant hip development, known as developmental dysplasia of the hip. The aim is to catch any problems before the child is six months old. Guidelines from the AAP suggest that girls with a family history of the condition or who were positioned feet-first in the womb in the third trimester should get a hip ultrasound at six weeks old or a hip x-ray at four months old.

There is some debate about whether all newborns should be screened, as most hip instability tends to correct itself. In general, a CT scan or an MRI is used to check the hip after treatment. Next steps after a positive screening will depend on the child’s age and the expert’s advice.

For newborns, those with risk factors but a normal exam should get a hip ultrasound at 6 weeks. If the exam is unclear or the hips click, the exam should be repeated in 2 to 4 weeks. If positive Ortolani or Barlow tests (tests for hip instability) occur, the baby should be seen by an orthopedic specialist.

For infants aged 4 weeks to 4 months, an unclear exam should lead to a consultation with a specialist or a hip ultrasound at 6 weeks. Positive results for Ortolani or Barlow tests should also lead to a referral to an orthopedic specialist.

For children older than 4 months, clinical examination is harder as hip looseness decreases, so other tests may not show positive results. Limited hip movement becomes the key sign to look for. X-ray is preferred over ultrasound for diagnosis since the femoral head nuclei (parts of the hip joint) begin to appear between 4 and 6 months of age. Normal X-rays at 4 months can rule out hip dysplasia for children with risk factors.

Ultrasound imaging is recommended to diagnose acetabular dysplasia, hip dislocation, anatomy of the femoral (thigh bone) head, ligament teres (in the hip), and the hip capsule. The crucial thing to identify is that the femoral head is covered by the hip socket (acetabulum) by at least 50%, and the alpha angle, which measures the depth of the hip socket. An angle greater than 60 degrees is considered normal. These criteria were established for static imaging diagnosis:

– The alpha angle: An angle of over 60 degrees between the hip socket and the ilium (part of the hip bone) is considered normal.

– The beta angle: The angle between the labrum (a ring of cartilage in the hip socket) and the ileum should be less than 55 degrees.

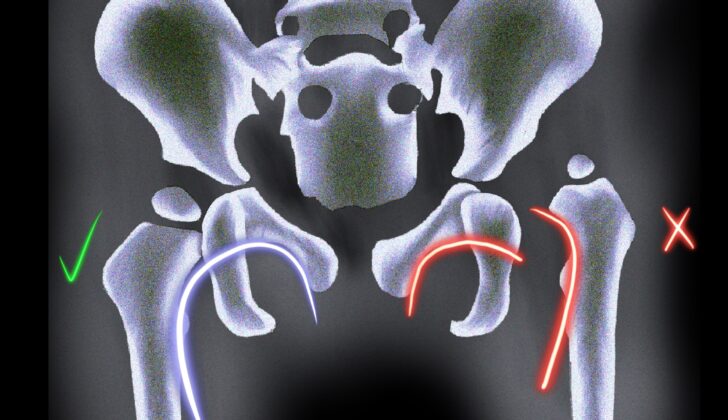

If x-ray is used to evaluate hip dysplasia, some signs can help identify abnormalities:

– Hilgenreiner line: If a horizontal line is drawn through the triradiate cartilage (the part of the hip bone where growth occurs) on both sides, the top of the thigh bone should be below this line.

– Perkin line: If a line is drawn at right angles to the Hilgenreine line starting at the side of the hip socket, the head of the thigh bone should be on the inside of this line.

– Shenton line: If a smooth curve is drawn connecting the neck of the thigh bone to the top edge of the obturator foramen (a hole in the hip bone), any disruption to this curve indicates an abnormality.

The acetabular index is the angle formed by the intersection of the Hilgenreiner line and a line drawn along the lateral (side) edge of the hip socket. It should be less than 35 degrees at birth and less than 25 degrees at the age of 1 year.

The center-edge angle of Wiberg is the angle formed by the Perkin line and a line drawn from the center of the thigh bone’s head to the side edge of the hip socket. This measurement is reliable in patients older than 5 years old and should be over 20 degrees.

Treatment Options for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

The treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), a condition where the “ball and socket” joint of the hip doesn’t properly form in babies and young children, is aimed at ensuring the normal growth of the hip joint. Ongoing monitoring is crucial to detect DDH early and avoid complications.

Treatment can vary based on the child’s age and the severity of the hip dysplasia.

– For newborns up to 4 weeks, if the hip is mildly unstable but not dislocatable, doctors might only observe it. If the hip is dislocatable, it is best to get an early referral to an orthopedic surgeon experienced with DDH. Sometimes, treatments like a splint that keeps the hip in the correct position, called abduction splints (such as a Pavlik harness), must be used.

– For infants between 1 to 6 months, a variety of abduction devices, including the Pavlik harness, can be used. These devices are worn nearly all day (23 hours) for at least 6 weeks or until the hip is stable. In this time, doctors usually check on the hip’s position every 3 to 4 weeks via ultrasound. If the hips aren’t reduced within 3 weeks, other more rigid abduction devices that keep the hip opened wide can be tried.

– For kids between 6 to 18 months, if they’re diagnosed with DDH at this age or if they didn’t respond to the abduction devices, a closed reduction with a hip spica cast is used. Closed reduction is a procedure where the hip is put back in the joint manually under anesthesia.

– For kids aged 18 months to 8 years diagnosed with DDH and those who didn’t respond to closed reduction, open reduction is chosen. Open reduction is a surgery to put the hip back into the joint. There can be some complications, like damage to the blood supply to the head of the femur.

For acetabular dysplasia, a situation where the “socket” part of the hip joint is shallow or tilted, treatments differ based on age. Up to 5 years old, children can be treated with part-time or full-time abduction orthosis. After 5 years, surgical procedures that involve making cuts to the pelvis to increase the socket’s size and ocrrect its position can be performed (if certain conditions are met).

Salvage pelvic osteotomies can be performed for patients older than 8 years with a partially dislocated femur head. Other surgical procedures involve placing extra bone to the side of the “socket” or moving the “socket” via pelvic bone cuts.

For teenagers and adults with hip pain, shallow socket and no evidence of hip degeneration, a surgical procedure that involves making multiple cuts to modify and reorient the “socket” while maintaining an intact back column (the backbone) can be performed.

What else can Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip be?

There are various conditions that could cause difference in leg lengths, including:

- A condition where the thighbone doesn’t develop correctly, known as proximal femoral focal deficiency

- A break or fracture in the neck of the femur (the long bone in your thigh)

- An abnormal inward curve of the femoral neck, known as coxa vara

- Long-term impacts of an infection in your joints, commonly referred to as infective arthritis

What to expect with Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

The long-term results of treating hip dysplasia in children can depend on several factors. These include the severity of the dysplasia, when the child was diagnosed, the type of treatment they have, and whether the hip joint was successfully re-aligned.

Around 90% of newborns with hip instability or mild dysplasia, which might be identified through a positive Barlow test (a physical exam technique), an alpha angle (an angle measured on an ultrasound of the hip) of between 50 and 60 degrees, and a certain amount of hip coverage, will see their condition improve on its own. These children typically have normal hip function and normal appearances on x-rays.

A treatment known as a Pavlik harness is successful in re-aligning the hip in approximately 95% of cases, with about one in five children having some remaining dysplasia. If hip dysplasia is not treated for a long time, it can lead to worsening disability and quicker onset of osteoarthritis, a condition causing joint damage and pain.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

If developmental dysplasia of the hip, a condition where the hip joint has not formed correctly, is not detected and treated, it can cause hip pain and an early onset of osteoarthritis. It can also cause problems with walking or movement. Some individuals might experience problems after being treated with a pelvic harness, which is used to correct the hip position. The most serious complication is avascular necrosis of the femoral head, a condition where the bone tissue in the hip dies from lack of blood, which can occur in anywhere from 0% to 5% of cases. This risk can be reduced with correct fitting of the harness.

Should a baby in a Pavlik harness, a specific type of pelvic harness, cease showing spontaneous straightening of the knee, it might indicate possible femoral nerve palsy, a nerve damage condition. This incidence is around 2.5%. It is usually seen in severe dysplasia cases or when the hip bend exceeds 120°. Femoral nerve palsy is generally resolved by removing the harness. However, hip dysplasia may still persist after harness treatment. To monitor this, X-ray checks should be conducted every six months or annually until the child’s skeleton has fully developed. A normal X-ray by the age of 2 indicates likely positive outcomes. Other complications can include skin irritation, erosion of the pelvis, and partial dislocation of the knee. During an open or closed reduction procedure, other complications such as re-dislocation, osteonecrosis, infection, and stiffness, can occur.

Preventing Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Swaddling a newborn improperly is a main cause for concern when it comes to developmental hip problems in babies. Therefore, before leaving the hospital, parents should be taught the correct way to swaddle their babies to prevent this condition. Parents should also understand the need for regular check-ups with the baby’s pediatrician. These check-ups will ensure that their child’s hips are developing correctly and can help spot any early signs of hip problems.