What is Laryngomalacia?

Laryngomalacia, characterized as the most common source of a baby’s high-pitched breathing noise, often requires early diagnosis as it can potentially impact a child’s growth and development. Key signs to look out for include this unique noisy breathing and other difficulty in breathing, which can reveal various levels of respiratory trouble and indicate abnormalities in the airways.

Detailed examination of the upper airways is essential for kids suspected of having laryngomalacia. This helps in accurately diagnosing the condition, figuring out the most suitable treatment strategy, and identifying any other existing or underlying health issues. It is important to remember that laryngomalacia can vary in its intensity.

For mild cases, it might be enough to simply monitor the baby closely without immediate medical intervention. However, severe laryngomalacia could increase the baby’s effort to breathe to the point that most of their energy from food goes into breathing, leading to them not gaining weight or growing properly. In such scenarios, surgery may be required.

This information presents a general outlook on today’s methods for diagnosing and managing laryngomalacia in babies.

What Causes Laryngomalacia?

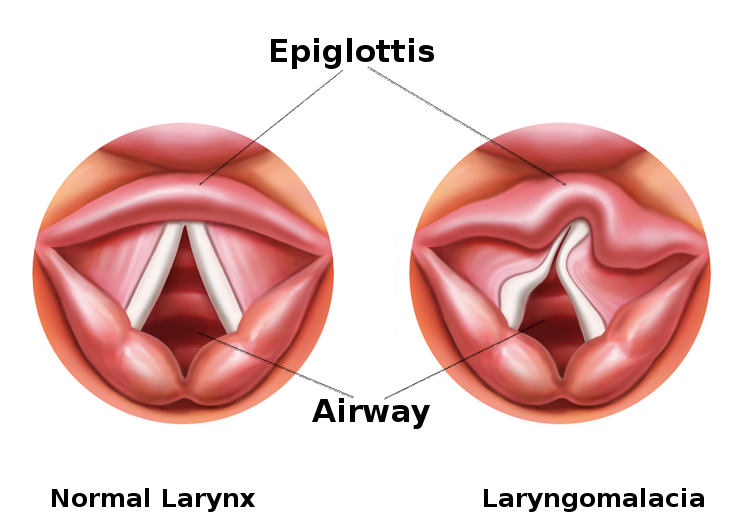

Laryngomalacia is a condition where the soft, immature cartilages of a baby’s voice box, or larynx, can’t hold their shape and collapse when the baby breathes in. This leads to noisy breathing, often referred to as inspiratory stridor.

Several theories try to explain why this happens. One main theory suggests that this condition could be due to a neurologic dysfunction. In other words, there might be some abnormal coordination between the nerves controlling the larynx, leading to the collapsing of the cartilages. This theory is supported by a study that found an increased nerve diameter in the upper part of the windpipe in patients with severe laryngomalacia.

Another theory, which needs further research, suggests that the problem could be due to a mismatch between the demand and supply when the baby inhales.

It’s important to note that while gastroesophageal reflux (when stomach acid moves up into the esophagus causing heartburn) has not been found to directly cause laryngomalacia, about 60% of infants with this condition also have acid reflux disease. This reflux might irritate and swell the upper airway, potentially worsening the obstruction caused by laryngomalacia.

Laryngomalacia is more likely to cause symptoms in infants with neuromuscular disease. This is because these infants have a global lack of muscle tone, including in the airway muscles, decreasing the overall strength of breathing in.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Laryngomalacia

It’s hard to exactly know how common laryngomalacia is in the average population. Some estimates suggest it affects anywhere between 1 in 2000 to 1 in 3000 people. This may be underestimated though, as mild cases of laryngomalacia often go undiagnosed. Despite earlier assumptions of it being more common in males, recent studies suggest it affects males and females equally. Black and Hispanic babies might have a higher risk than white babies. Some factors that may be linked to laryngomalacia include low birth weight, prematurity, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit shortly after birth.

- Laryngomalacia happens in about 1 in 2000 to 1 in 3000 people, but this might be underestimated.

- Contrary to earlier thoughts, laryngomalacia is equally common in males and females.

- Black and Hispanic babies might be more at risk than white babies.

- Factors like low birth weight, early birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission after birth could be related to laryngomalacia.

Signs and Symptoms of Laryngomalacia

To diagnose and manage a baby who is suspected of having laryngomalacia, doctors need to know the full birth history of the infant. This would include any operations or uses of a breathing tube, as well as any time spent in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Parents should inform doctors about any breathing issues they’ve noticed, such as loud breathing or pauses in breathing. These symptoms, especially if they get worse during feeding or when the baby is lying on their back, could hint at laryngomalacia. The healthcare provider should also ask about the baby’s feeding and sleeping patterns, and check for any weight loss, acid reflux, repeated bouts of pneumonia, or failure to thrive (not growing or developing normally).

The doctor should conduct a thorough physical examination of the baby, paying special attention to the mouth, nose, and neck. They need to ensure the baby’s nostrils are not blocked (choanal patency) and rule out a condition where the opening between the nostrils is too narrow (piriform aperture stenosis). It’s crucial to examine the inside of the baby’s mouth to check for conditions like a split in the lip or roof of the mouth (cleft lip or palate), an abnormally positioned tongue (glossoptosis), a small lower jaw (Pierre-Robin sequence or micrognathia) as these can cause issues with breathing and feeding. Ideally, the doctor should observe the baby both sitting and lying down during a feed.

The neck should be checked carefully for any abnormal swelling when the baby is breathing, or for any lumps or vascular abnormalities. The chest should also be examined, using a stethoscope to listen to the baby’s breathing and looking for signs that the baby is having to work hard to breathe (such as the skin pulling in below the ribcage). Special attention should be paid to reddish birthmarks in a beard-like distribution over the skin, as these are sometimes associated with a rare condition called “occult airway hemangioma” where similar birthmarks can be found in the airway.

If a baby is suspected of having severe laryngomalacia, they should have a procedure called a flexible laryngoscopy, where doctors use a thin, flexible tube with a camera on the end to look at the area above the voice box (supraglottic airway). If there are severe symptoms, this procedure would ideally be done while the baby is awake. If problems are identified, doctors may need to carry out more detailed examination which may involve a rigid laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy, and possibly treatment with instruments passed down the scope, which would require the baby to be asleep in an operating room.

Testing for Laryngomalacia

Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy is a common tool used for diagnosing noisy breathing, or ‘stridor’, in babies. This procedure uses a thin, flexible, fiber optic viewing instrument to visualize the upper part of the digestive and respiratory tract (aerodigestive tract) while the baby is breathing. This helps doctors to see the back of the throat, the area above the vocal cords (supraglottis), the vocal cords themselves (glottis), the area below the vocal cords (subglottis), and the entrance to the voice box (hypopharynx).

Typically, babies with a condition called laryngomalacia have certain characteristics such as shortened folds near the voice box, or an unusual shaped part of the voice box which can be seen through this instrument. The laryngoscopy is considered best for diagnosing laryngomalacia since it allows doctors to directly see the upper part of the airway during regular breathing in an awake baby. However, it’s vital to remember that around 5% of babies with laryngomalacia might also have other structural issues in their lower airway that cannot be detected by laryngoscopy alone.

In cases where the symptoms are severe, or if there’s a concern for additional airway issues, direct laryngoscopy and diagnostic bronchoscopy are performed in the operating room. These procedures allow for a more comprehensive view of the upper digestive/respiratory tract down to the level of the bronchi, which are the main airways leading into the lungs. If necessary, these methods also allow for surgical procedures.

If there’s any concern about a swallowing issue or aspiration (when food, stomach acid or saliva is inhaled into the lungs) then a radiologic study may be advised. This study involves a modified barium swallow test. It’s particularity useful in babies with laryngomalacia, as aspiration in such cases often goes unnoticed.

A sleep study, or polysomnogram, can assess if the baby has obstructive sleep apnea, a condition where breathing stops involuntarily for brief periods during sleep. This sleep disorder is quite rare but if diagnosed, surgical intervention may be beneficial. A special type of procedure to improve their sleep apnea symptoms can be planned.

Lastly, airway fluoroscopy, which is an imaging technique that uses X-rays to obtain real-time moving images of the airways, isn’t usually recommended for diagnosing stridor in infants. This is because it is not particularly sensitive and it also exposes the baby to ionizing radiation.

Treatment Options for Laryngomalacia

Laryngomalacia is a condition that occurs in babies and results in a soft, floppy larynx (voice box). The majority of infants with laryngomalacia, particularly those with mild or moderate symptoms such as stridor (a high-pitched, wheezing sound caused by disrupted airflow), can be treated conservatively. This usually means keeping a close eye on the child’s weight gain and checking for any severe symptoms. In some cases, adjusting the baby’s feeding position and thickening their food can help manage any feeding difficulties. Most children overcome these symptoms by the time they’re 12 to 18 months old without needing any surgery.

However, between 10% to 20% of infants with laryngomalacia will have more severe symptoms. These infants often need surgery to help them breathe and eat properly. A supraglottoplasty is the most common surgical procedure for severe cases where other treatments have not worked. The surgery involves modifying the overhead part of the voice box to ease airflow. The procedure varies depending on the child’s specific anatomy but could include shortening some tissues, removing excess tissue, modifying the shape of the epiglottis (a flap of cartilage at the base of the tongue), or a combination of these techniques. It’s essential to avoid certain areas during this procedure since scarring could lead to further complications.

The supraglottoplasty procedure has been proven to significantly reduce the duration of laryngomalacia symptoms. Patients usually handle the procedure well and are monitored in the hospital afterward. Steroids are typically administered during surgery and in the recovery period to help reduce inflammation in the airway.

What else can Laryngomalacia be?

When considering if a child has laryngomalacia, doctors will take into account other possible causes of infant stridor (noisy breathing). These include:

- Unilateral or bilateral vocal fold paralysis: This typically occurs after a neck or thoracic cavity surgery or can be present from birth. Symptoms include a hoarse cry and potential feeding difficulties. If there is significant respiratory distress, a tracheostomy may be required. Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy is used for diagnosis.

- Laryngeal papillomatosis: This can cause a hoarse cry and upper airway obstruction, often presenting early in infancy. Diagnosis is made using flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy or direct laryngoscopy and biopsy of the lesions.

- Subglottic hemangioma: This is a rare cause of stridor, usually expiratory. Confirmation of this condition is achievable with direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy.

- Subglottic stenosis: This is usually present from birth, though it may also occur due to prolonged intubation. Stridor may be present but does not change with the infant’s position.

- Tracheomalacia or bronchomalacia: These could be present along with laryngomalacia. Expiratory airway sounds are generally present and a bronchoscopy is used for diagnosis.

- Vascular ring: This is a rare cause of airway obstruction with symptoms including feeding difficulties and stridor. A contrasted CT scan of the chest is used to confirm this diagnosis.

- Foreign body aspiration: This can occur if an infant has been left unattended or has had a coughing or choking event after eating. Diagnosis is suggested with chest x-ray findings and decreased unilateral breath sounds. Bronchoscopy should be performed to diagnose and retrieve the foreign body.

By considering all these possibilities, doctors can arrive at the most accurate diagnosis.

What to expect with Laryngomalacia

Traditionally, it is believed that most patients tend to get better by the time they reach 12 to 18 months of age. However, a recent study suggested that there isn’t much proof to support this, and the resolution age could actually vary greatly. Most infants usually improve simply with treatments like being fed upright, using therapies to control the reflux, and carefully monitoring any respiratory symptoms.

A small group of patients might need surgical treatment known as a supraglottoplasty. The operation has a high success rate, with some studies indicating that it works for as many as 95% of cases. Nonetheless, patients who undergo a supraglottoplasty might need more surgery if the symptoms persist. This is most likely to occur in patients who were younger than two months when they had their first surgery, and those with conditions affecting the nerves like hypotonia (reduced muscle strength), seizures, cerebral palsy, or heart conditions like septal defects and high blood pressure in the lungs.

Among these, nerve conditions are the most associated with requiring more surgery, with almost 70% of patients requiring another operation. Around 60% of these patients end up needing a tracheostomy, a procedure that creates an opening in the neck for breathing, due to a persistent blockage in the airway.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Laryngomalacia

Inhaling food or liquid into the lungs, a condition known as aspiration, is not commonly associated with a surgical procedure known as supraglottoplasty, regardless of the surgical method used. The risks of aspiration after surgery usually relate to certain factors, such as neurological conditions, having had more than one surgery, and being less than 18 months old at the time of surgery.

For a condition called laryngomalacia, nonsurgical treatments generally focus on addressing accompanying instances of acid reflux. The common strategy is to employ a type of medication known as a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). It has been observed that severe laryngomalacia can often go hand-in-hand with acid reflux. However, using PPI therapy hasn’t always been proven to alleviate symptoms of laryngomalacia consistently.

Key Points:

- Aspiration is rare after a supraglottoplasty.

- Neurological issues, repeat surgeries, and being under 18 months old at the time of surgery are factors linked with increased aspiration risks post-surgery.

- Nonsurgical treatments for laryngomalacia primarily focus on managing accompanying reflux disease.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are often recommended, but their effectiveness isn’t consistently proven to improve laryngomalacia symptoms.

Preventing Laryngomalacia

It’s crucial for parents to understand the symptoms of laryngomalacia, a condition where the voice box isn’t fully developed, particularly that noisy breathing doesn’t always mean the child isn’t developing properly. Indeed, some children who breathe loudly can still grow and develop normally and this noisy breathing can often continue even after surgery.

Parents should be informed that treatments primarily involve non-invasive approaches, but it’s necessary for the child to have regular check-ups to keep track of any worsening symptoms. It’s also important that any prescribed medications are taken as instructed.

Another crucial point for parents to understand is the need for feeding adjustments. Compliance with feeding strategies such as giving the child thickened feeds and adjusting their position during feeding, is essential in managing the condition.