What is Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma?

The first known record of a condition called nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (NA) goes back to the time of the ancient Greek doctor, Hippocrates, in the fifth century B.C.[1] This condition is often called juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA), juvenile angiofibroma (JAF), or fibromatous or angiofibromatous hamartoma of the nasal cavity.[2] The term “nasopharyngeal” might not be completely accurate as some sources say the issue might stem from the sphenopalatine foramen and the back part of the nasal cavity,[1][3] while others suggest a choanal and nasopharyngeal origin.[4]

All researchers agree that JNA is harmless (benign), but it has a large number of blood vessels. It represents about 0.05 to 0.5% of all masses found in the head and neck.[5] Although benign, this condition can showcase aggressive features, spreading into the nose’s wind tunnels (nasal turbinates), nasal septum, and medial pterygoid lamina. It frequently grows into the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, and pterygopalatine fossa, and in larger lesions can reach into the sphenoid, maxillary, and ethmoid sinuses. The condition can also grow through the inferior orbital fissure, into the masticator space through the infratemporal fossa. In extreme situations, the disease might involve the orbital and brain regions (intracranial involvement), which is seen in about 10 to 37% of cases.[8]

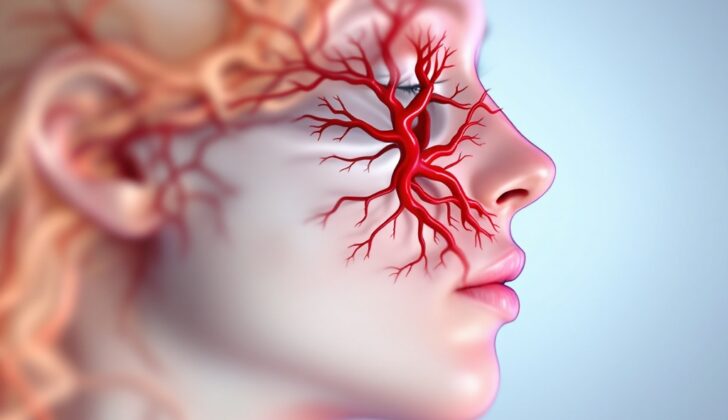

As previously stated, JNA is a highly vascular lesion, meaning it has one or more arterial connections. The most common primary blood supply is the internal maxillary artery, a branch of the external carotid artery.[9] Larger lesions might have multiple feeding arteries, maybe even involving both sides. The ascending pharyngeal artery is the second most common large supplying branch of the external carotid artery. Additional accessory arteries can include the middle meningeal, accessory meningeal, and facial artery branches. Some studies also note the inclusion of internal carotid artery branches, most commonly the vidian artery, and to a slightly lesser extent the eye’s artery (ophthalmic artery).[10]

What Causes Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma?

The exact cause of Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma (JNA), a rare benign tumor that occurs in the nasal cavity of adolescent males, is not fully understood. There are several theories discussed in medical research. One theory suggests a blood vessel source, such as an unusual bundle of blood vessels known as an Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM), or leftovers of an early structure seen in embryo development known as the first branchial arch. These remnants could likely explain the usual place of the angiofibroma near the sphenopalatine foramen, a passage at the back of your nasal cavity.

The tumor is usually high in blood supply; this might be due to the expression of specific growth signals for blood vessels, primarily vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2).

Some believe that JNA may be connected to hormones influencing the growth of blood-carrying tissues after repeated minor bleeding and repair incidents. Some research has found androgen, estrogen, and progesterone receptors in these tumors. Some think this could be why JNA mostly occurs in adolescent boys. During puberty, androgen (a type of male sex hormone) increases and might stimulate the growth and expansion of the tumor’s blood supply.

However, JNA can continue to grow even after treatment when testosterone (a specific androgen) is given, bringing into question the role of hormones. This idea also gets complicated because some older women (with reduced estrogen and progesterone) have developed this tumor. Additionally, some pregnant women, who have high levels of sex hormones, have developed this tumor too. So, the role of hormones in JNA is not yet entirely clear.

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma has also been linked with genetic abnormalities and certain conditions. Cases of deletion of a certain part of chromosome 17 have been reported. This location on the chromosome also contains two important genes related to cancer growth, TP53 and HER2. Other conditions linked with JNA include Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) and Gardner syndrome, which involve changes to the APC gene, known to play a role in tumor growth.

More recent research has linked JNA with Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection. HPV is known for its role in causing head and neck cancers. A small study found a strong link between JNA and HPV. This could raise concerns for an increase in JNA cases considering the global increase in HPV rates. However, due to limited evidence, there’s a need for more research in this area.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, also known as JNA, is a type of head and neck tumor that mostly occurs in adolescent boys. It is a rare condition accounting for about 0.05 to 0.5% of these types of tumors. The number of people who get this kind of tumor varies from 1 in 150,000 to 1 in 1,500,000. People from India and the Middle East have been reported to be more likely to get it than those of European origin.

The typical age that people get this disease is between 9 and 25 years old. There have been some cases of older males being diagnosed, but this is considered rare. Although extremely uncommon, there have been reports of females getting this disease too. In these cases, further genetic tests are usually conducted. This is due to the rare nature of the disease in females, which could suggest that certain genetic factors might be causing the disease.

Signs and Symptoms of Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

A common issue often experienced by teenage boys is long-term blockage in one nostril. There may also be pain-free nosebleeds that happen without any clear reason. Other complaints may include headaches, runny nose, and if the issue is severe, it could lead to bulging eyes, problems with vision, facial nerve paralysis, problems with the tube that connects the throat and the middle ear, and even changes to the shape of the face. During a physical check-up, doctors typically spot a lump within the nose.

Testing for Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is a condition where a specific type of tumor appears in the nasal cavity. It’s diagnosed through a combination of physical examination procedures and medical imaging technology. There isn’t any laboratory test that can confirm this condition.

Your doctor might examine your nose with a tool called a nasal endoscope. It’s a thin, flexible camera that helps to see what’s going on inside the nose. During this examination, they might find a firm, delicate, reddish, or purplish lump inside the nasal cavity if this condition is present.

Medical imaging is used to get a more detailed look at the situation. This could involve computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These scans use different techniques but can both produce clear, detailed images of the body’s soft tissues and bones, revealing issues that may not be apparent with a physical exam. In some cases, X-rays might also be used to see if the back wall of your cheek’s sinus has been moved forward because of a growing mass.

A CT scan with a special, contrasting dye might show a brightly highlighted soft tissue mass located at the back of the nasal cavity near an opening called the sphenopalatine foramen. The tumors can grow large enough to block or invade the hollow cavities in your skull that contain air or sinuses. CT scans are used in such cases because they can help determine the extent of the tumor and if the tumor has caused changes in the bone shape or caused the bone to be destructed.

CT scans are great for seeing the details of bone involvement but MRI scans complement them by providing superior clarity in soft tissue contrasts. In other words, MRIs provide a clearer image of the soft tissues involved. The tumor will appear in particular color intensities in non-contrast MRI scans. Previous cases of bleeding can be seen, highlighted on a specialized kind of MRI scan known as susceptibility-weighted imaging. Some characteristics of the tumors can also be seen on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) scans. The MRI images can show the tumor lighting up brightly after a gadolinium contrast liquid is given. Also, MRI scans are good at showing whether the tumor has grown into a network of veins in the brain, the sphenoid sinus, or the nerves in the base of the skull or around the eyes. Similar to the CT scan, the MRI can show if the illness has caused the arteries in question to enlarge.

The tumor associated with nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is very vascular, which means it has many blood vessels. Due to this, a biopsy (a procedure where a small piece of tissue is taken to examine) is usually not considered for diagnosing this condition – there’s a high risk of serious blood loss if a biopsy is conducted, and it could even lead to life-threatening situations.

Treatment Options for Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

The recommended treatment for such tumors is usually by removing them through surgery. This concept dates back to the times of Hippocrates, which involved a procedure akin to splitting the ridge of the nose.

Because the tumor has many blood vessels, preoperative embolization is often done to reduce the risk of bleeding during surgery and possible complications. This also helps to map out the vascular supply, especially the arteries feeding the tumor. The procedure is often carried out through the femoral artery, using substances such as gelatin sponge, particles, or micro coils to block the blood vessels supplying the tumor. This allows doctors to better isolate and remove the tumor during surgery, especially when dealing with larger, more advanced tumors.

Over the years, various surgical methods have been developed to remove nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, including techniques that involve different surgical ‘corridors’, like through the palate, face, nose, upper lip, or the side of the jaw. Nowadays, many cases are now treated endoscopically (using a flexible tube with a light and camera attached to it), which often involves making a small incision in the nose. During the surgery, the surgeon will aim to cause minimal disturbance to the tumor itself, instead focusing on surrounding areas to determine the size and location of the tumor. They will also aim to minimize blood loss and reduce damage to surrounding tissues. In some cases, depending on the size and location of the tumor, some parts of the bone may need to be drilled or resected to allow complete removal of the tumor.

If the tumor is large, doctors might opt for a segmented approach, removing parts of it in stages, based on each section’s blood supply. This can help manage excessive blood loss and limit the risk of complications, especially when an artery from the brain supplies blood to the tumor, which cannot be blocked using embolization. In rare cases, there might be a need to expand bone openings, or even repair tears in the protective outer layer of the brain to prevent blood and cerebro-spinal fluid from mixing, which could lead to severe complications like infection of the brain’s lining.

While surgery remains the first choice, radiation therapy can be used as a secondary treatment for remaining or recurring disease, particularly for advanced tumors that have invaded critical areas and cannot be completely removed by surgery. However, there is some debate over this due to concerns about the long-term side effects, including the possibility of inducing another cancer due to the high doses of radiation. There are different types of radiation therapies available, each with its own success rates and potential complications. However, pre-operative radiation therapy can also make subsequent surgeries more difficult and increase the risk of complications due to changes in the tissues caused by the radiation.

Another possible treatment is hormone therapy using androgen receptor blockers, which can help reduce the size of the tumor ahead of surgery or in case of a recurrence. These medications are not a cure in themselves but can aid in the overall treatment strategy.

There is limited evidence supporting the use of chemotherapy or other cytotoxic drugs in the treatment of this condition. The few cases that have been treated with these drugs have shown varying responses, indicating the need for further research to establish their effectiveness.

What else can Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma be?

There are several other medical conditions with symptoms that look like Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA), making it a challenge to diagnose sometimes. Here are some of these conditions:

- Olfactory neuroblastoma: This is a type of tumor that starts from the nasal cavity. It tends to light up during imaging tests and can grow into the brain. It often affects women more than it does men.

- Rhabdomyosarcoma: This is a cancer that starts from the striated muscle, which is a muscle that can be seen in areas like the eyes and the nose. When this cancer affects the head or neck, it mostly happens inside the eye but can also happen in the nose and neck areas. It usually affects children under 12 years of age.

- Sinonasal polyp: This is a growth that occurs due to repeated inflammation in the nose or sinus. It is less vascular compared to JNA and rarely causes nose bleeding. It typically doesn’t grow into the sphenopalatine foramen or pterygopalatine fossa, which are areas inside the skull related to the nose and mouth.

- Encephalocele: This is a condition where some parts of the brain protrude out of the skull due to a skull defect. The type that happens in the nose or nasopharynx can look like a nasal cavity mass. However, they are usually located more to the front of the face compared to JNA and they don’t light up during imaging tests.

- Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: This is a cancer that starts on the walls of the nasopharynx, which is the upper part of the throat behind the nose. It is common in adults between the ages of 40 to 60 years and rare in children or teenagers. It usually shows a light, even enhancement during imaging tests, as opposed to the heavy enhancement seen in JNA. It also tends to eat away at bone structures including the clivus, a part of the skull base.

What to expect with Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is a non-cancerous condition, which means it typically has a good outcome. The main issue with this condition, also known as JNA, is when it’s so advanced that doctors can’t completely remove it, or if it comes back after treatment.

According to studies, as many as 33% of advanced cases cannot be fully removed. Additionally, in those cases that have been operated on, the condition can return in 30 to 38% of patients. This can lead to more health problems due to the growth and invasion of the leftover or returning tumor.

Some patients with leftover or returning disease might need additional radiation therapy. Although rare, there have been cases where secondary cancers, such as basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma, have developed within the area treated by the radiation.

Very rarely, JNA can turn into cancer, primarily into well-differentiated tumors after radiation therapy. There are also reports of it transforming into a type of cancer called undifferentiated sarcomatous, causing a worse outcome.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

The biggest risk for people with Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma (JNA) is losing a lot of blood, mainly during surgery. This can be life-threatening if doctors don’t take the right precautions. The tumor can also invade the orbit of the eye, which may push the eye forward (exophthalmos), change the face or eye shape, cause vision loss or impact the movement of the eye. Vision can also be lost if non-targeted embolization is used and it accidentally includes the branches of the internal carotid artery.

Before surgery, embolization can sometimes have severe complications like artery spasms, facial paralysis, stroke, or injury to the cranial nerves. Mild complications can include swelling in the face, discomfort or strange sensations, headaches, or nausea and vomiting. Surgery itself can lead to similar complications, but also scar the patient and alter facial appearance. If hormonal therapy is used, this could unintentionally lead to feminization in teenage boys, which can be seen as undesirable, or even as a complication.

Common Complications:

- Significant blood loss

- Exophthalmos (eye bulging out)

- Changes to face or eye shape

- Vision loss

- Loss of eye movement

- Artery spasms

- Facial paralysis

- Stroke

- Injury to cranial nerves

- Facial swelling

- Physical discomfort or strange sensations

- Headaches

- Nausea and vomiting

- Scarring

- Facial deformity

- Feminization in adolescent boys (with hormone therapy)

Recovery from Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

To check for any leftover or returning disease, regular check-ups and medical imaging are necessary. Spotting leftover disease can be challenging as the key sign to look for in imaging, known as tumor/tissue enhancement, can also show up in healthy tissue that’s healing, especially in images taken not long after surgery. During this stage of recovery, a physical exam and your symptoms become important, often in addition to imaging. Most cases of the disease coming back are seen in the first 6 to 36 months after surgery. Therefore, follow-up appointments should be scheduled as often as twice a year for at least four years after surgery.