What is Acanthamoeba Keratitis?

Acanthamoeba is a type of protozoan found everywhere, including places like water, soil, and dust. First discovered in 1974, Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) is a serious eye infection that can threaten your sight and has a potentially bad outcome, largely due to delays in diagnosis. The causes of AK appear to be linked to many factors, but most cases are linked to the use of contact lenses and their cleaning solutions.

In the past 20 years, more people are using contact lenses, and this increase, along with poor hygienic practices and improper handling, has led to a rise in risk for eye infections, especially bacterial keratitis and AK. AK is a painful condition that can seriously affect your vision and impact your quality of life.

AK can be mistaken for other types of keratitis, often leading to wrong diagnoses and delayed treatment. It can show symptoms that fluctuate over time, and in severe cases that don’t resolve, a therapeutic surgery may be required to save a person’s sight. AK is a rare eye condition, affecting 1 to 9 people per 100,000 individuals. However, it is becoming more common in Western countries due to its link with contact lens use, which is the main risk factor for this condition.

Up to 93% of AK cases are reported in people who wear contact lenses, highlighting the strong connection between this eye infection and contact lens use. Several risk factors contribute to the occurrence of AK, including not cleaning your contact lenses properly, wearing them overnight, prolonged use, using lenses while swimming and showering, exposure to polluted water, eye injuries, and the use of contaminated contact lens solution. Those who use disposable contact lenses are at a higher risk, and orthokeratology has been identified as another contributing factor, with an annual rate of 7.7 cases per 10,000 people.

Acanthamoeba is a free-living protozoan found in freshwater and soil. This organism can exist in two different forms: an inactive cyst form, and a moving trophozoite form. The cyst form, which has lower metabolic activity, can withstand extreme conditions such as temperature changes, dry weather, shifts in pH, and anti-amoeba drugs. Even with advancements in diagnostic and treatment methods, cases of AK are still missed or delayed frequently, leading to detrimental effects on the patient’s outcomes and quality of life. A delayed diagnosis can lead to deeper eye involvement, requiring urgent surgery to restore the normal eye structure and vision.

What Causes Acanthamoeba Keratitis?

Acanthamoeba is a type of organism that falls under the Amoebozoa phylum, Lobosa subphylum, and Centramoebida order in the biological classification system. Acanthamoeba is pretty versatile. It can live in various environments such as soil, water bodies like ponds, swimming pools, hot tubs, and even in contact lens solutions.

There are many different types of Acanthamoeba species, classified from T1 to T12 based on the 18s rDNA sequence analysis. The T4 type is often linked with AK, a type of infection. Among these, Acanthamoeba castellani and Acanthamoeba polyphaga are generally the most common species responsible for causing AK.

Acanthamoeba organisms can exist in two forms: an active one (trophozoite) and a dormant one (cyst). Trophozoites feed on bacteria, algae, and yeast. They can move slowly and can multiply through asexual reproduction. The cystic form is quite tough—it’s not very active metabolically but can withstand severe environments like drastic temperature or pH changes, high UV light exposure, lack of food, and dryness.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Acanthamoeba Keratitis

Acanthamoeba Keratitis (AK), an eye infection, is becoming more common. Although it’s traditionally considered a rare form of keratitis, research shows that it’s responsible for about 5% of eye infections connected to contact lenses. Primarily, contact lens wearers get AK, with the number of cases varying from 1 to 33 per million people who wear lenses each year. This discrepancy is due to regional differences in types of contact lenses, the contamination levels of water at home and public pools, and how often tests for AK are used.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that storing contact lenses in water or refilling lens solution can increase your chances of getting AK by approximately 4.46 and 4.38 times, respectively. Even though poor lens care is commonly linked to AK, it can also happen to people who clean their lenses well. Most lens cleaning solutions don’t effectively kill Acanthamoeba. However, solutions with hydrogen peroxide have proven to be successful against this organism.

AK has also been reported in people who don’t wear contact lenses, especially those frequently exposed to dust, soil, or contaminated water.

Anyone can get AK, but it usually affects those who are aged 40 to 60, or younger. People with weaker immune systems have a higher risk of developing AK. It should be noted that AK affects males and females equally.

Signs and Symptoms of Acanthamoeba Keratitis

It’s crucial for medical professionals to take a detailed history of a person showing signs of an eye infection. They need to take note if the person uses contact lenses, has recently suffered any eye injuries, or has been exposed to dust, soil, or contaminated water. This information can help identify Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK), a specific type of eye infection. AK usually affects just one eye, and a key symptom, even at the start, is intense pain that seems out of proportion to the condition itself. This is thought to be caused by certain enzymes produced by the infection. Sufferers often describe symptoms like blurry vision, a red eye, feeling like there’s something in their eye, sensitivity to light, tearing, and discharge. How severe these symptoms are can change.

It’s worrying to know that between 75% to 90% of people with early-stage AK are wrongly diagnosed at first. This highlights how important it is for medical professionals to suspect AK when patients have symptoms for multiple weeks and there’s no improvement, even with a daily regimen of antibiotics or antiviral eye drops. There’s a chance for another bacteria-related superinfection if symptoms get worse, even with the right initial treatment.

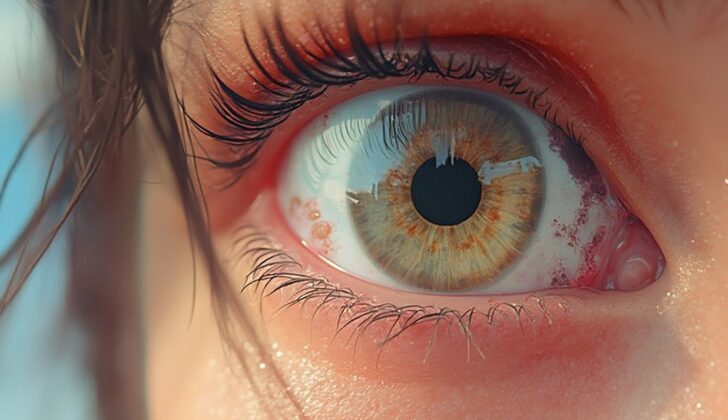

A thorough examination of the eye is vital for people with suspected eye infections. A device called a slit-lamp is used for the early eye examination and can often reveal certain conditions such as punctuate keratopathy, epithelial infiltrates, pseudodendrites, and perineural infiltrates (details seen in the image of Acanthamoeba Keratitis). Perineural infiltrates, which are quite common in AK, can be seen in up to 63% of cases around six weeks in, but they may disappear as the condition worsens. Late-stage AK has specific visual features, including “ring-like” stromal infiltrate and inflamed corneal nerves. Additionally, there can be satellite lesions, ulceration, collection of pus under the cornea, and epithelial defects.

Interestingly, the ring infiltrate is found in about 50% of people with advanced AK. Advanced AK can cause thinning of the cornea and could even lead to corneal perforation. Since many of these findings are not exclusive to AK, clinicians should be suspicious of AK, especially when the patient’s history and other features strongly suggest it.

- Early Symptoms:

- Eye pain disproportionate to the condition

- Reduced vision

- Eye redness

- Foreign body sensation

- Photophobia (light sensitivity)

- Tearing and discharge

- Indicative Examination Findings:

- Punctate keratopathy

- Epithelial infiltrates

- Pseudodendrites

- Perineural infiltrates

- Advanced Symptoms :

- Stromal thinning

- Corneal perforation

- “Ring-like” stromal infiltrate

- Radial keratoneuritis

- Satellite lesions

- Ulceration, abscess formation

- Anterior uveitis with hypopyon

- Epithelial defects

It’s estimated that 75% to 90% of AK cases are initially misdiagnosed. Common misdiagnoses for AK include herpetic keratitis (47.6% of misdiagnosed cases), mycotic keratitis (25.2%), and bacterial keratitis (3.9%).

Testing for Acanthamoeba Keratitis

The gold standard for detecting Acanthamoeba, a kind of amoeba that can cause infections in the eyes, has traditionally been the plate culture technique. But more and more, other methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM), and staining are becoming common.

To be able to test for it, a small sample from your cornea (the clear, front layer of your eye) must be collected. This is usually done through corneal scraping or biopsy. These samples are then tested using different staining methods. Specific stains can help identify the double-walled structures, or ‘cysts’, of Acanthamoeba. Identifying these under the microscope can sometimes be a bit tricky.

One of the main advantages of these staining techniques is that they can deliver results quickly. The effectiveness of these stains varies, but they are generally quite good at spotting the presence of the cysts. However, traditional cultures have a detection rate of only 40% to 70% for Acanthamoeba, and the results can take up to a week.

PCR testing is a newer method that has proven very successful in detecting Acanthamoeba. It is widely available, quick, and less labor-intensive than older methods. Many believe that PCR could become the new gold standard for this diagnosis. PCR is also valuable because it can spot Acanthamoeba whether it’s alive or not, potentially confirming positive results.

For those patients whose cultures don’t show Acanthamoeba but still have severe symptoms, a corneal biopsy may be recommended. Periodic acid Schiff staining on this biopsy sample can reveal the presence of Acanthamoeba cysts.

Also, doctors sometimes find it helpful to test a patient’s recent set of contact lenses and lens case using culture and PCR techniques. It’s important to remember that these items can test positive for Acanthamoeba even in people without symptoms.

IVCM, another detection method, allows doctors to look at individual corneal cells in real-time. While this technique can be costly and not always available, it is useful for tracking the disease progression and treatment response. Likewise, confocal microscopy is a rapid, noninvasive test capable of identifying only the double-walled cysts. Cytology smears, which use stains to detect the Acanthamoeba in tissue samples, are fast, straightforward, and widely available.

A group of stains, including lactophenol-cotton blue, Giemsa, CFW, and acridine orange, are regularly used for their speed and accuracy. Still, some of them could lead to false positives due to debris. The silver stain becomes necessary when scientists need specific cyst shapes. According to some studies, hematoxylin and eosin staining might be the most accurate.

Scientists have been exploring several innovative diagnostic techniques for diagnosing AK. One of them, LAMP, has also demonstrated a high accuracy, similar to PCR. Furthermore, two noninvasive imaging techniques, HRT II, and NMR spectroscopy, are being studied, but further exploration is needed to determine their effectiveness.

Treatment Options for Acanthamoeba Keratitis

Acanthamoeba, a type of amoeba, has different forms — the active, disease-causing form, called trophozoites, and a dormant form, called cysts. The active form can be killed with a variety of medications like antibiotics, antifungals, and more. The dormant cysts, however, are a lot tougher and can resist most treatments, leading to long-lasting infections.

Two types of medicines, diamidines and biguanides, are typically used first when treating Acanthamoeba Keratitis, a serious eye infection caused by the amoeba. Alone or combined, they can treat the infection successfully in between 35% to 86% of cases. If these therapies don’t work, other medical and surgical treatments may be used.

There are many available drug therapies for Acanthamoeba Keratitis, each working in different ways to stop the growth of the infection. Biguanides and diamidines, for example, work by interfering with the amoeba’s cell functions and DNA production. Other drugs, like aminoglycosides, stop the amoeba from making proteins, while imidazoles destabilize the cell wall.

These drugs are typically used in stages, with certain concentrations and dosages being used at different points in the treatment plan. For example, the initial treatment might involve hourly doses of certain drugs for two to three days. As the patient recovers and the infection subsides, the dose frequency may decrease.

Diamidines and biguanides work by changing the cell membranes in the amoeba, causing the cell to break down. There are several types of diamidines that can be used, all at a 0.1% concentration. They are usually well-tolerated but might cause eye surface damage if used for prolonged periods.

One study found that chlorhexidine, a type of biguanide, was slightly more effective than another biguanide, PHMB, with higher rates of infection clearing and vision improvement. That said, recent research suggests that using PHMB alone at a higher concentration could be just as effective as combining it with other treatments.

Early, intense treatment is key because this can destroy the cysts before they fully mature. This means delivering the medicine every hour, day, and night, for the first two days. After that, the frequency can be reduced and slowly tapered off over six months to a year to ensure no cysts survive.

In cases where the initial treatments don’t work, other drugs and even surgical procedures may be considered, including corneal cryoplasty, amniotic membrane transplantation, and a procedure using riboflavin and UV-A light. These are typically reserved for more serious cases.

Inflammation outside the cornea signals a more severe form of the disease and requires treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs. The use of topical steroids is controversial due to concerns they might actually promote cyst growth and increase the number of trophozoites. Using these steroids needs careful consideration and should always be done alongside anti-amoebic treatments. And, if steroids are used, the anti-amoebic treatments should go on a few weeks after the steroids are stopped.

Research into new treatments, including silver nanoparticles, titanium dioxide and UV-A combinations is ongoing, but these are not yet ready for use in humans. If inflammation persists despite these treatments, surgeries such as penetrating keratoplasty (PK) or deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) may be required.

What else can Acanthamoeba Keratitis be?

A study found that almost half of all patients with a condition known as Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) were initially misdiagnosed as having simple herpes eye infection. The two can look a lot alike, but there are differences – for example, the erosions seen in AK don’t get wider at the ends, which is a characteristic feature of herpes eye infections. There are other signs, too, such as ring-like infiltrations and nerve involvement, that suggest AK rather than herpes. In some cases (10-23%), AK can actually co-occur with a herpes infection.

It’s also possible for AK to be confused with bacterial or fungal eye infections. Those can cause the same type of ring-like infiltration often seen in AK. However, unless there’s a secondary infection, AK is more likely to present with multiple points of transparent infiltration, while bacterial and fungal infections usually show thicker infiltrates. Moreover, bacterial infections are more likely to spread beyond the corner of the eye.

In some cases, the signs of AK can resemble those of fungal infections. But the translucent defects, nerve involvement, and ring infiltrations, seen through a special device called a slit-lamp, may indicate AK. Again, fungal infections are more likely to spread further. Plus, a fungal culture can confirm the presence of a fungus.

Patients with AK are often younger than those with bacterial or fungal infections, and they might have symptoms for a longer period before they see a doctor. However, since AK can exist alongside bacterial and fungal infections, it’s not entirely clear how much age and other patient factors should play a part in diagnosing.

To identify AK, doctors need to consider and rule out several other conditions, including:

- Contact lens-associated keratitis

- Eye inflammation (conjunctivitis)

- Dry eye

- Herpes eye infection: which presents with specific types of ulcers

- Recurrent corneal erosion

- Staphylococcal marginal keratitis

- Fungal keratitis: which shows thicker infiltrated and is typically focused in one spot

- Bacterial keratitis

In AK, the lack of end bulb and the presence of transparent, dot-like infiltrates can help doctors make an accurate diagnosis and distinguish AK from other eye conditions. Detecting AK early is important, as proper treatment needs to be started promptly.

What to expect with Acanthamoeba Keratitis

The outcome for patients with AK, or Acanthamoeba keratitis, largely depends on how severe the disease is when it’s diagnosed and how quickly treatment can begin. If diagnosis is delayed, the patient may be left with corneal scars, which can lead to a poor outcome. On the other hand, patients who start treatment within three weeks of the first symptoms generally have good vision results.

The prognosis can worsen if the patient also has cataracts, or if the disease has spread beyond the cornea. An elective procedure called PK may be an option to improve vision, but usually, experts suggest waiting until the infection has cleared and treatment has been paused for at least three months. The specific type of Acanthamoeba causing the disease does not appear to affect the prognosis of AK.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Acanthamoeba Keratitis

Several complications can arise from Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK), an infection in the eye. These complications include things like glaucoma, iris damage, eye adhesions, cataracts, and persistent defects in the innermost layer of the cornea. In rare cases, people may experience issues like scleritis (a serious eye inflammation), sterile anterior uveitis (an inflammation inside the eye), inflammation of the retina and blood vessels, and inflammation of the vascular layer of the eye.

Scleritis, which is seen in about 10% of AK cases, is thought to be the result of an inflammatory response of unknown cause rather than a direct invasion of the Acanthamoeba, a type of amoeba. To manage inflammation outside the cornea, suitable anti-inflammatory treatments are used.

Recovery from Acanthamoeba Keratitis

After a treatment for Acanthamoeba Keratitis (AK) like TPK, the patient typically gets treated with anti-Acanthamoeba drugs such as PHMB and chlorhexidine. These are given 6 to 8 times daily and can be adjusted depending on how the patient responds. If the condition comes back, their treatment could be increased to every 1 to 2 hours for a minimum of 2 to 3 weeks.

Steroids are added to the treatment 3 weeks later while continuing the use of anti-Acanthamoeba drugs. Initially, they are given 3 times a day. If there are no signs of the condition returning, the steroid usage can be adjusted as follows: increased to 4 times a day for 3 months, then cut down to 3 times a day for the next 3 months, then 2 times a day for a further 3 months, and then once a day until the graft survives.

In addition to all these, certain medicines, cycloplegics like Atropine and Homatropine, and anti-glaucoma drugs like Timolol, should also be used to help protect the eye.

Regular check-ups are extremely important for the patient’s recovery. Through this, we can quickly identify and handle any potential complications or if the condition comes back, which in turn helps improve the patient’s vision and overall eye health.

Preventing Acanthamoeba Keratitis

It’s important to educate everyone, especially those who wear contact lenses, on how to prevent a condition known as Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK). Part of this education includes important tips, such as not wearing contact lenses overnight, avoiding homemade saline solutions, and keeping lenses off while swimming or showering. Using throwaway daily lenses instead of reusable ones might help decrease the potential for AK, but more research is needed to confirm this.

People who often come into contact with dirt, soil, or possibly contaminated water should remember to wear appropriate protective glasses. In addition, when doctors are more knowledgeable about how Acanthamoeba keratitis develops, they’re better equipped to handle their patient’s needs.