What is Acute Retinal Necrosis (Kirisawa’s Uveitis)?

Acute retinal necrosis (ARN) is often caused by an infection of a certain virus like varicella-zoster or herpes simplex. This condition usually impacts the outer parts of the retina. Normally, ARN is seen in individuals with a healthy immune system, though it can also affect people with weaker immune systems. The condition can affect one or both eyes; when both eyes are involved, it’s called bilateral ARN (BARN).

ARN was first identified in Japan in 1971 when six cases were explained that featured inflammation of the eye, an inflamed retinal artery, areas with dead retina cells, and a detached retina. In Japan, the condition is sometimes referred to as Kirisawa’s uveitis.

What Causes Acute Retinal Necrosis (Kirisawa’s Uveitis)?

Acute retinal necrosis is a condition that’s generally caused by members of the herpes virus family. These can include the varicella zoster virus (VZV), the herpes simplex virus (HSV), and less commonly, the cytomegalovirus (CMV) or Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). The most frequent cause though is the VZV.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Acute Retinal Necrosis (Kirisawa’s Uveitis)

Acute retinal necrosis, an eye condition, affects people regardless of their immune system’s strength. It is common in both men and women. Generally, it tends to show up in older groups as their immunity to the Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) decreases over time. Younger individuals who have had herpetic encephalitis, a type of brain inflammation, can develop retinitis caused by the Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV).

This condition can also occur in people whose immune systems have been suppressed through the use of medications like corticosteroids, other types of immunosuppressant drugs, and chemotherapy. It’s also seen in people with HIV/AIDS and others with weakened immune systems.

There are certain genetic patterns, known as HLA-Aw33, HLA-B44, and HLA-DRw6, which have been associated with acute retinal necrosis in the Japanese population. Similarly, American Caucasians with HLA-DQw7, HLA-Bw62, and HLA-DR4 have also been known to experience this condition.

Signs and Symptoms of Acute Retinal Necrosis (Kirisawa’s Uveitis)

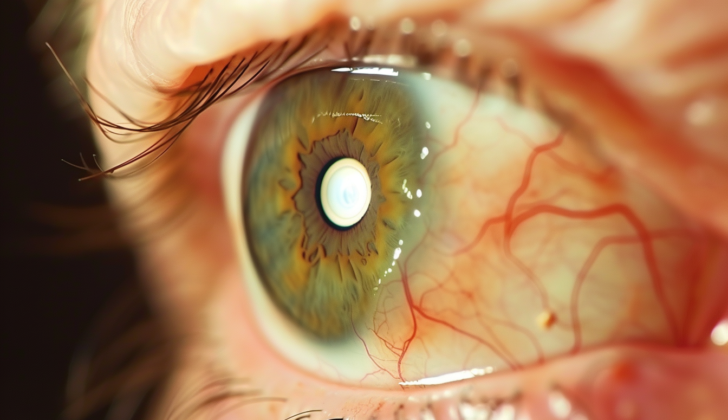

People who have problems with their eyes may quickly experience eye or area around the eye pain, pain when moving the eye, redness, sensitivity to light, floating spots in the field of vision, reduced or blurred vision, or a narrowing field of vision. Doctors will need to know about any risk factors for AIDS, the patient’s immune system health, any previous eye or body treatments/ surgeries, diseases, and any history of herpes virus infection, including brain infections. It’s also important to review any old medical records in detail.

Doctors will then perform an eye exam that checks the front part of the eye and the jelly-like substance in the eye, eye pressure, as well as an expanded check of the back of the eye with a special tool and by gently pressing on the eyeball. The physical check may show a specific, easy-to-spot areas of eye whitening suggesting eye inflammation or destruction on the back surface of the eye. The check also often shows blockage in the small arteries and a strong immune response in the jelly-like substance of the eye and the front part of the eye. The back center of the eye is usually not affected in the early stages of the disease. Other possible signs include redness of the thin membrane that covers the white part of the eye, inflammation of the white part of the eye, increased eye pressure, small arteries in the retina with a sheath around them, bleeding in the retina, swelling of the optic disc, and detachment of the retina.

A common patient has severe inflammation of the front part of the eye with fibrous material with or without adhesions in the back. The substances that fill the eye are usually misted due to mist in the front part of the eye, inflammation of the jelly-like substance in the eye with or without clouding of the lens making it difficult for light to pass through to the retina. The check of the interior surface of the back of the eye may show swelling of the optic disc and peripheral yellowish areas of inflammation of the back surface of the eye which then join together. Bleeding in the retina, if present, usually isn’t very noticeable.

In cases of acute retinal necrosis, there might be evidence of a certain type of inflammation of the small arteries around the artery.

Testing for Acute Retinal Necrosis (Kirisawa’s Uveitis)

Acute retinal necrosis (ARN) is a condition that is mainly diagnosed based on symptoms, and treatment often can’t wait for final test results. The classic symptoms of ARN include: 1) inflammation of the blood vessels in the retina and choroid (the layer of blood vessels and connective tissue between the white of the eye and the retina), 2) widespread retinal necrosis (death of tissue), which is more common in the peripheral retina, and 3) significant inflammation in the jelly-like material in the eye, also known as vitritis.

The American Uveitis Society has set certain criteria for diagnosing ARN. This includes specific areas of retinal necrosis in the peripheral retina, rapid increase of necrosis without antiviral therapy, evidence of blood vessel abnormalities, and a significant inflammatory reaction in the vitreous and the front part of the eye. Other supporting symptoms are damage to the optic nerve, inflammation of the white part of the eye, and eye pain.

The retinal necrosis can be categorized into three zones. Zone 1 is around the center of the fovea and the margin of the optic disc, and any retinitis here can immediately threaten sight. Zone 2 is the area between Zone 1 and the clinical equator, marked by the anterior margin of the vortex ampulla. Zone 3 lies anterior to Zone 2, up to the ora serrata (the serrated boundary between the retina and the ciliary body).

A patient who shows symptoms of ARN must undergo several tests. These include a complete blood count, liver and kidney function tests, HIV testing, syphilis tests (FTA-ABS and RPR), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, analysis for toxoplasmosis titers (a measure of antibodies), purified protein derivative skin test, and a chest x-ray. These tests are done to rule out other causes of their symptoms.

In less clear-cut cases, a sample from the anterior chamber of the eye or vitreous can be taken to test for herpesviruses and toxoplasmosis. While these tests can help confirm an ARN diagnosis, treatment should not wait for these results.

Intravenous fluorescein angiography, a technique for examining blood circulation in the back of the eye, can also be used. Optical coherence tomography, a non-invasive imaging test, of the macula (the part of the retina responsible for sharp, central vision) and optic nerve may reveal cystoid macular edema or disc swelling. Ultrawide field fundus photography may help track the progress of the disease. An ultrasound of the eye may prove helpful to rule out a detached retina. If a doctor suspects intraocular lymphoma, tertiary syphilis, or encephalitis, a CT scan or MRI of the brain, as well as a lumbar puncture, should be performed.

Treatment Options for Acute Retinal Necrosis (Kirisawa’s Uveitis)

Immediate treatment is needed for this condition, and it can be given whether the patient is hospitalized or not. The aim is to decrease the likelihood of the other eye getting affected. One particular study demonstrated that treatment with antiviral medication kept a significant number of patients free from the disease in their second eye two years later. However, it’s important to understand that this treatment does not prevent the risk of retinal detachment in the first eye.

There are several antiviral medications that can be used for treatment, such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. These medications can be given orally or intravenously, depending on the severity of the condition. In some cases, injections into the eye may be necessary.

In addition to antiviral medication, corticosteroids may be prescribed to reduce inflammation and protect the optic nerve. Pain relievers and steroids may also be considered if there is an anterior chamber reaction.

Prophylactic barrier laser photocoagulation may be an option to consider, as it may be able to prevent eventual retinal detachment. However, this approach is controversial and not always used in standard practice.

In cases of retinal detachment, early surgical intervention should be planned. However, it’s important to note that even with successful reattachment of the retina, vision improvement may be limited due to optic atrophy and other factors.

The visual outcomes after retinal detachment are associated with how much the optic nerve was involved. Better visual outcomes are typically seen in cases where the optic nerve was not severely affected.

What else can Acute Retinal Necrosis (Kirisawa’s Uveitis) be?

When doctors consider the causes of certain eye conditions, there are many possibilities they often have to check for:

- CMV Retinitis: Typically seen in patients with weak immune systems. Clear vision (no or only slight inflammation) and noticeable blood flow are two main identifying factors. Usually starts affecting the back of the eye.

- Progressive Outer Retinal Necrosis: This is seen in patients with a weak immune system. Key characteristics include no eye inflammation, effects on the outer retina, early impact on the back of the eye, and minimal blood flow. Clear areas around blood vessels may be noticed.

- Syphilis: This causes inflammation of the eyes, impacts the back part of the eye, blockages in the retinal artery, and round cloudiness in the eye. Other signs of syphilis may include changes in skin especially around hand and feet.

- Toxoplasmosis: High eye inflammation, an area of the eye affected by inflammation can be seen through the cloudiness of the eye. An old scar near the inflamed eye area is often visible. In extreme cases other symptoms such as brain involvement is seen.

- Behcet Disease: People with this disease will usually have mouth ulcers, skin and genital lesions. In their eyes, there will be inflammation, cloudy spots, limited blood flow in retina, and patches of inflammation of the retina. A specific gene (HLA-B51) might be identified. Sometimes, a skin inflammation test might appear positive.

- Fungal or Bacterial Endophthalmitis: Individuals might experience significant pain, redness, swelling of the eyelids, sensitivity to light, cloudy cornea, and, occasionally, corneal infection. In some cases, eye discharge or thickening of the choroid (part of the eye) might be visible upon ultrasound. A sample obtained from an eye may test positive for bacteria or fungi.

- Panuveitis due to other causes.

- Large Cell Lymphoma: This typically appears in older individuals. There might be eye opacity, eye inflammation, and orange-colored lesions under the retina. Behavioral change might accompany these symptoms. A biopsy from the vitreous part of the eye might show lymphoma cells. It also might be shown through brain imaging.

What to expect with Acute Retinal Necrosis (Kirisawa’s Uveitis)

The future outlook for eye health in cases of ARN (Acute Retinal Necrosis) is generally poor, with 64% of affected eyes ending up with a vision of less than 20/200. This is due to several complications such as detached retina, abnormality in the macular region of the eye, issues with the optic nerve (optic neuropathy) and lack of adequate blood supply to the retina (retinal ischemia).

However, with early diagnosis and treatment, visual outcomes may improve. In fact, up to 92% of eyes may reach at least 20/400 vision and almost half of the affected eyes might reach a final vision of at least 20/40. Early treatment can also reduce the chances of both eyes getting affected.

From a large series of cases, the observation was made that the disease affecting the area closest to the center of the retina (zone 1) and involvement of the optic disc (the spot where the optic nerve enters the eye) were associated with a final vision of 20/200 or worse.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Acute Retinal Necrosis (Kirisawa’s Uveitis)

ARN, also known as Acute Retinal Necrosis, may lead to several complications. These complications can affect various parts of the eye, including the retina, the optic nerve, and the vitreous (the clear jelly-like substance inside your eye).

Here are the potential complications you may experience:

- Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, retinal necrotic breaks, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, vitreous traction: These terms all refer to damage or changes to the retina, the light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye, and the vitreous.

- Exudative retinal detachment: This is a condition where fluid accumulates under the retina, causing it to separate from the underlying layer.

- Optic neuropathy: This involves damage to the optic nerve, which transfers visual information from your eye to your brain.

- Retinal ischemia: This occurs when there is insufficient blood flow to the retina.

- Epiretinal membrane: A thin layer of scar tissue that forms on the surface of the retina.

- Cystoid macular edema: This is when fluid collects in the macula, the part of the eye responsible for sharp, clear vision.

- Pigmentary retinopathy after healing of ARN: This refers to the changes in the retina’s pigmented cells after the resolution of ARN.

- Cataract with posterior synechia: This is when a clouding of the lens is accompanied by a bridge of tissue in the eye.

- Glaucoma: This condition involves increased pressure in the eye, which can damage the optic nerve and result in vision loss.

- Vitreous haze: This complication results in a clouding or blurring of vision due to inflammation in the vitreous.

- Vitreous hemorrhage secondary to retinal and optic disc neovascularization: This is bleeding into the vitreous, typically triggered by the formation of new, fragile blood vessels on the retina or optic disc.