What is Central Retinal Vein Occlusion?

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) stands as the second most frequent type of vein disease in the retina and often leads to vision loss in older individuals. There are two kinds of RVO: Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) and Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). Central retinal vein occlusion refers to a blockage in the main vein of the retina often due to a blood clot, and it’s subdivided into two categories: non-ischemic (with blood flow) and ischemic (without blood flow). On the other hand, Branch retinal vein occlusion represents a blockage in one of the smaller branches of the central retinal vein.

Most commonly encountered is the non-ischemic CRVO, making up about 70% of the cases. Patients with this condition usually maintain a decent level of vision, can have minor or no issues with pupil response, and experience mild visual changes.

The ischemic CRVO, accounting for about 30% of cases, might occur primarily or develop from a non-ischemic CRVO, although this progression isn’t common. Nearly half of ischemic CRVO cases get better without treatment. However, it is associated with a poorer vision outcome, and around 90% of patients with vision worse than 20/200 have this condition. Ischemic central retinal vein occlusion is characterized by at least 10 areas in the retina with no blood flow. It’s also referred to as complete, non-perfused, or hemorrhagic retinopathy.

What Causes Central Retinal Vein Occlusion?

The main risk factor for the development of a condition called central retinal vein occlusion, where there is a blockage in a vein in your eye, is age. Most patients with this condition are over 50 years old. Other risk factors include high blood pressure, open-angle glaucoma (an eye condition that can lead to vision loss), diabetes, and high levels of fat in the blood.

Smoking, certain conditions that affect the optic disc (a part of your eye), and diseases that cause your blood to clot too much can also lead to this condition. Several other risk factors include certain diseases and conditions, taking oral contraceptives or diuretics, abnormal platelet function (which helps your blood clot), diseases affecting the eye socket, and rarely migraines.

Anything that reduces blood flow out of the veins, damages the veins, or makes your blood more likely to clot increases your risk of developing central retinal vein occlusion. Certain risk factors can lead to the central retinal vein (a vein in the eye) being squeezed by the central retinal artery (an artery in the eye). In glaucoma, high pressure inside the eye can block blood flow out of the retina, causing stasis (stoppage or slowdown of blood flow). However, sometimes the exact cause of this condition can be hard to identify.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

Central retinal vein occlusion, a main cause of sudden, non-painful vision loss in adults, is fairly prevalent. In developed countries, for every 1000 people, around 5.2 experience retinal vein blockages and 0.8 experience the specific condition of central retinal vein occlusion.

Signs and Symptoms of Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO) is a condition that affects the eye. People with CRVO usually notice that their vision becomes blurry or distorted in one eye, and this change happens all of a sudden. The good news is that this vision loss doesn’t come with pain. However, if they experience symptoms like tingling sensations, eye movement challenges, muscle weakness, blurry speech, drooping eyelids, and abnormal reflexes, this may suggest a different health issue other than CRVO.

Depending on the specific kind of CRVO, patients’ experiences may differ. Some might have mild visual disturbance, while others suffer from significantly reduced vision. The same goes for physical examinations – some may show normal results, while others may reveal specific changes in the affected eye, including a condition called afferent pupillary defect, weakened color vision or reduced clarity of vision.

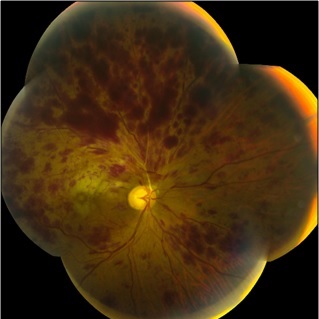

The appearance of the interior surface of the eye (seen through a special instrument called an ophthalmoscope), in cases of CRVO, is usually likened to a stormy weather (“blood and thunder”) due to the widespread bleeding spots throughout the retina. Other possible observations in the eye could include white fluffy patches on the retina (“cotton wool spots”), damage to the layer of nerve fibers in the retina, and a swollen optic disc (the area where the optic nerve enters the eye).

In cases of non-ischemic CRVO (a less severe type of CRVO), there is usually abnormal twisting and slight widening of the retinal veins, as well as bleeding in all sections of the retina. In ischemic CRVO (a more serious type of CRVO), there is usually notable swelling in the retina, widened veins and extensive bleeding in the retina.

Testing for Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

When a person is diagnosed with a central retinal vein occlusion, which is a blockage in one of the veins returning blood from the retina, a variety of laboratory tests are necessary to determine the cause. Everyone diagnosed with this condition should have the following tests:

* Blood pressure test: to measure the force of blood against artery walls

* Erythrocyte sedimentation rate: a test that checks for inflammation in the body

* Complete blood count: measures the number of each type of blood cells

* Random blood glucose: to check the sugar level in the blood

* Random total and HDL cholesterol tests: to check the types and amount of fats in your blood

* Plasma protein electrophoresis: a test that looks for abnormal proteins that can be linked to multiple myeloma (a type of blood cancer)

* Tests for urea, electrolytes, and creatinine: to evaluate kidney function, which can be linked to high blood pressure

* Thyroid function tests: to check if the thyroid gland is working properly; this might be linked with abnormal blood lipid levels

* EKG: a test that records heart’s electrical activity, used to detect heart problems like enlargement of the left part of the heart, which might happen due to high blood pressure

Additional tests are required for patients who are under 50 or have a history of clots forming in veins (thrombosis) or a family history of thrombosis:

* Chest x-ray: to look for lung diseases like sarcoidosis or tuberculosis

* C-reactive protein test: measures a protein that indicates inflammation in the body

* Thrombophilia screen: checks for issues with blood clotting

* Autoantibodies: these tests look for markers of autoimmune diseases

* Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme test: to check for certain conditions like sarcoidosis

* Fasting plasma homocysteine test: to measure a certain type of amino acid in the blood linked to heart disease

* Treponemal serology: checks for syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease

* Carotid duplex imaging: uses ultrasound to see if there are blockages in the carotid arteries, which might contribute to ocular ischemic syndrome (a condition causing sight loss due to reduced blood flow to the eye)

These tests are necessary to better understand and manage the condition.

Treatment Options for Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

As of now, no complete cure exists for either the prevention or treatment of central retinal vein occlusion, a condition that affects the eye. When this condition occurs, a molecule called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) increases, leading to swelling and the growth of new blood vessels in the eye, which can easily bleed.

Treatment often involves injections directly into the eye of a medicine that blocks VEGF, which helps reduce the growth of new blood vessels and the swelling. Several different medical treatments have been tried with varying degrees of success, including aspirin, anti-inflammatory drugs, blood thinning agents, and different types of injections directly into the eye. Some of these injections include a clot-busting drug called alteplase, a drug called ranibizumab, a steroid called triamcinolone, a drug called bevacizumab, a drug called aflibercept, and a slow-release implant of the steroid dexamethasone.

Surgery can be another method of treatment, which might involve using a laser to make scars in the retina, creating a new pathway for blood to drain from the eye, or removing part of nerve at the back of the eye. Another option is a vitrectomy, a surgery to remove the jelly-like substance in the middle of your eye.

There are some specific surgical and laser techniques that might help improve vision in people with central retinal vein occlusion. If the condition is accompanied by blood leakage in the eye, a type of surgery called pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) can be carried out to clear the blood leakage and improve the view of the retina. Furthermore, PPV can be used to get rid of the new blood vessels that can lead to increased eye pressure or glaucoma. A type of laser treatment called pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) can be done to treat the new blood vessels. The aim here is to stop some of the retina’s function to prevent further new blood vessels from growing and treat iris neovascularization. However, there is no proof at this time that shows preventive PRP without neovascularization is beneficial.

What else can Central Retinal Vein Occlusion be?

When diagnosing central retinal vein occlusion, a condition relating to the eyes, doctors usually rule out the following similar conditions:

- Ocular ischemic syndrome

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy, a diabetic eye disease

- Hyperviscosity retinopathy, a blood disorder that affects the eyes

- Branch retinal vein occlusion, a blockage of the smaller veins that carry blood away from the retina

These conditions can show similar symptoms and it’s crucial to differentiate them through proper testing and examination for accurate diagnosis.

What to expect with Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

Younger patients tend to recover better from central retinal vein occlusion. Of every three seniors with this condition, one gets better without treatment, one remains the same, and one worsens. If the occlusion doesn’t become ischemic, around 50% of patients may get their vision back to normal or near-normal levels. Persistent swelling of the macula, known as chronic macular edema, is the main reason for poor vision.

Prognosis often depends on the initial clarity of vision:

- If initial vision clarity is 20/60 or better, it’s likely to stay the same.

- If vision clarity is 20/80-20/200 initially, the outcome can vary, possibly improving, remaining the same, or worsening.

- If the initial vision clarity is worse than 20/200, it’s unlikely to improve.

When central retinal vein occlusion is ischemic, the prognosis becomes more uncertain due to the potential for macular ischemia – insufficient blood supply to the macula. These patients have a high risk of developing a type of severe eye condition called neovascular glaucoma. This usually happens within 2 to 4 months and is due to the formation of new blood vessels in the iris (rubeosis iris) in 50% of cases. Retinal neovascularization, which is new blood vessels forming on the retina, occurs in 5% of the eyes.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

When the central retinal vein gets blocked, it causes a lack of oxygen or hypoxia in the retinal tissues. This triggers the release of a growth factor called VEGF and inflammatory substances. The problems that can occur as a result of this include swelling of the macula (the part of the retina that provides the most precise vision), bleeding within the eye, and a specific type of glaucoma called neovascular glaucoma.

This macular swelling, or edema, can cause significant vision loss in people who have a blockage in the central retinal vein. Injections into the eye of substances that block VEGF have been found to reduce this swelling and improve vision.

New blood vessels growing on the iris, or iris neovascularization, is a development in two out of three cases of central retinal vein blockage where blood supply to the retina is severely affected (ischemic). Once iris neovascularization occurs, a third of these cases go on to develop neovascular glaucoma. About 10% of all these cases also experience a blockage in the branches of the retinal artery. The main risk factors for iris neovascularization include poor vision, large parts of the retina not receiving enough blood (capillary nonperfusion), and blood trapped inside the retina.

Recovery from Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

If a patient has a non-ischemic central retinal vein occlusion, meaning their retinal vein isn’t blocked by a clot, their first follow-up visit should be 3 months later. However, they should come in earlier if their vision gets worse. Patients who do have an ischemic central retinal vein occlusion (where their retinal vein is blocked), need to be checked monthly for 6 months. This is to look out for new blood vessels growing in the front part of their eye or a case of neovascular glaucoma, a specific type of eye pressure problem. Here, a detailed eye check called a gonioscopy is conducted before pupils are dilated at each visit.

For those treated with medicine to stop blood vessel growth, known as anti-VEGF agents, they need to continue observation for the same period after they stop taking the medicine. Furthermore, patients should be monitored for up to 2 years to check for any significant lack of blood flow (ischemia) and fluid buildup in the macula (macular edema), which is the center of the retina that helps with detailed vision.

Preventing Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

If someone experiences a sudden loss in their vision, it’s crucial that they see an eye doctor immediately or visit the emergency room. Everyone should know that losing your vision suddenly is not normal. If you experience this, contact a healthcare expert right away.