What is Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy?

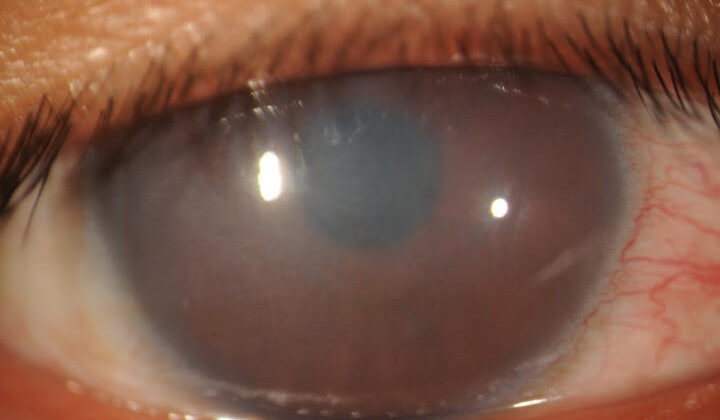

Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED) is a condition that causes cloudiness in both eyes. This usually appears at birth or shortly afterward due to a genetic mutation affecting the rear part of the cornea.

This cloudiness is due to an increase in corneal thickness and fluid accumulation in corneal tissue resulting from this genetic mutation. Current treatments for CHED involve surgical procedures to graft a new corneal tissue either via penetrating keratoplasty (PK) or endothelial keratoplasty (EK).

Recent research has revealed that treatment with specific anti-inflammatory drugs might be beneficial for certain variations of this disease. It’s important not to delay treatment for CHED as it can lead to poor vision development and even vision loss in one eye known as amblyopia.

What Causes Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy?

In the past, a condition known as congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy used to be divided into two types. However, these two types are no longer seen as separate. Now, the condition is simply referred to as CHED and is a hereditary non-progressive disease that causes cloudiness in the cornea during birth.

The cause of CHED is due to a mutation in a specific gene called SLC4A11, which is located on chromosome 20p13. This gene’s role is to code for a certain protein that keeps the balance of fluid in the cornea. When this gene gets mutated in CHED, the protein can’t work properly, leading to swelling, disruption of collagen fibers, and corneal thickening, leading to corneal cloudiness.

It’s interesting to note that the SLC4A11 gene is also involved in other parts of the body like the inner ear and kidneys, implying that other conditions might coexist with CHED. Moreover, this gene can also cause Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) and Harboyan Syndrome. Harboyan Syndrome has the same symptoms as CHED but also includes gradual hearing loss from ages 10 to 25.

Sometimes, CHED is connected to other gene mutations as well, suggesting that the disease might be caused by a range of genetic changes. That being said, not all CHED patients have this gene mutation, indicating that it could be due to different genetic causes in some cases. For instance, some mutations have been found in patients with similar conditions but no mutation in the SLC4A11 gene.

In 2016, a unique case of CHED was reported in a 45-year-old woman, characterized by a later onset of the disease. Genetic testing confirmed that the disease resulted from new mutations affecting the SLC4A11 gene. While this delayed onset might have been due to her socioeconomic situation and lack of access to healthcare, it is also possible that these specific mutations only mildly affect BTR function, causing a delayed onset of CHED symptoms.

People with a family history of CHED or who are closely related to each other have a higher risk of their babies being born with the disease. Therefore, it is advised that families with a child diagnosed with CHED consider genetic counseling due to a 25% chance of recurrence in future children.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy

A study noted in 1998 looked at over a million births in Spain, finding the occurrence of a condition called congenital corneal opacities in newborns to be not very common (3.11 for every 100,000 newborns, to be exact). As of now, we don’t know exactly how common CHED, which is a different issue affecting the eye, is. However, we have mostly found it in children who have parents related by blood from Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, India, and Ireland, and have a family history of a disease that harms the cornea, a part of the eye.

Signs and Symptoms of Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy

For a child with blurry or hazy vision (corneal opacification), it’s crucial to discuss when the symptoms began with the child’s family. This is especially important for older children who have not yet received treatment. Symptoms might include reduced vision, amblyopia (lazy eye), nystagmus (uncontrolled eye movement), and potential hearing loss.

In early infancy, pendular nystagmus, which is a specific type of uncontrolled eye movement, might be present. However, it’s often not easily noticeable due to its small size, making it tricky to identify. It’s important to note that nystagmus seems to be more common in patients with severe vision cloudiness.

Upon detailed eye examination (slit-lamp examination), a congenital condition that affects the cornea known as hereditary endothelial dystrophy usually appears as swelling in both corneas. This typically begins when the child is a newborn. The cornea might appear blue-gray and hazy but, in severe cases, can completely obscure the vision.

Testing for Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy

Doctors can further evaluate the functioning of the blood vessels and their ability to allow fluids through by using a method known as fluoro-photometry. It’s also important to measure eye pressure as there are chances of glaucoma, an eye condition causing damage to the optic nerve. However, increased pressure due to thicker corneas may lead to a false high result.

If this issue arises, doctors will look for additional signs of congenital glaucoma such as enlarged corneas, particular types of streaks on the cornea, known as Haab striae, and an abnormal increase in the eye’s size, a condition named buphthalmos.

A hearing test might also be necessary because of a condition called Harboyan syndrome, which combines congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (a condition that affects the eyes) with hearing loss. This hearing loss usually does not appear until age 10 to 25 and there have been no reported cases of it being present before learning to speak. Some research suggests that over time, all individuals with this eye condition will also develop hearing loss, as shown in studies on mice with a disrupted SLC4A11 gene.

Treatment Options for Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy

The primary treatment for congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy, a rare eye condition, is currently through surgery. Two types of surgeries used to treat it are Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK) and Endothelial Keratoplasty (EK). PK involves replacing the whole thickness of the cornea, while EK includes replacing the back layer of corneal cells in two ways: through Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK) and Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK).

PK was traditionally the main treatment. However, it’s a complex process for children due to their bodies’ characteristics. Risks associated with PK surgery include frequent loosening of stitches and increased risk of infection, unpredictable changes in eye shape after surgery, and the likelihood of kids not following post-surgery instructions.

DSAEK is gaining popularity since it offers a quicker recovery of vision, stable refractive error, and lower chances of lazy eye and traumatic eye injury due to its small incision. It showed better outcomes for children and infants, with less complications and quicker recovery. Although beneficial, DSAEK also has potential complications. It can be challenging because children’s eye structures are different – their clear inner lens and small eye chamber can complicate surgery, especially for infants.

On the other hand, DMEK is a newer procedure that can provide better results than both DSAEK and PK but is often more challenging to perform, especially in infants.

Additionally, some researchers found that providing children with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) could be a non-surgical method of treatment. However, more research and clinical trials are needed to figure out the best way to use these drugs for treatment. Overall, while surgery remains the leading treatment method for this eye condition, new advancements present a promising future for the management of congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy.

What else can Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy be?

For a child with a foggy or unclear cornea, diagnosing the cause can be challenging, as it could stem from many different conditions. To assist, we can use the acronym “STUMPED” which stands for:

- Sclerocornea

- Tears in Descemet’s Membrane

- Ulcers

- Metabolic Disorders

- Peters Anomaly

- Endothelial Dystrophy

- Dermoid

“Sclerocornea” is a birth defect that can cause blurry vision and a whitish appearance in the outer part of the eye.

“Tears in Descemet’s Membrane” usually happens due to a rough birth process where forceps were used. The vision problem arises from a tear in one of the eye’s inner layers, causing swelling and cloudiness.

Ulcers in the cornea of the eye can raise the possibility of an infection. These can be caused by viruses like herpes simplex or bacteria. If not treated, they could scar the cornea and may need surgical intervention.

Then we have a group of “Metabolic disorders” including Mucopolysaccharidoses, Cystinosis, and Mucolipidosis IV. They are caused by various genetic factors and may cause a cloudy cornea during the first year of life.

“Peters Anomaly” is a condition where the cornea fails to separate from other parts of the eye properly, causing blurry vision and often other eye problems.

In “Endothelial Dystrophy,” the patient has a clouded cornea because of long-term swelling that doesn’t change over time.

Lastly, there’s “Dermoid,” which presents as patches that could obstruct vision. The size varies, but if they are big enough to interfere with vision, they might need to be surgically removed.

It’s crucial to accurately diagnose these conditions as each requires different care. For instance, thickened corneas can give a false increase of pressure inside the eyes, leading to a misdiagnosis of glaucoma. As well, a child with congenital glaucoma may show a cloudy cornea, so it’s essential to identify any other symptoms of glaucoma before giving it as a diagnosis.

Different forms of corneal dystrophy can present as clouded corneas with varying degrees of severity and progression. Careful observation and examination are necessary to distinguish these conditions accurately.

What to expect with Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy

The outcome of a patient’s treatment depends on several factors including how severe the disease is, the patient’s age when they begin treatment, and any other medical conditions they may have. Starting treatment at a younger age can prevent vision problems and helps with better eyesight development, but it also comes with a higher risk of complications from surgery.

Generally, young patients with a genetic eye condition known as congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED) who receive corneal transplant treatment (PK) often have better survival rates for the transplant and can significantly improve their vision. However, two studies in 2017 suggested that the results of this treatment may not be as effective in CHED patients due to the body rejecting the transplant and poor vision outcomes after surgery.

Despite PK being a common treatment, more and more doctors are preferring to perform a type of corneal transplant known as DSAEK. This is because it is associated with better outcomes for the patient, less complications, faster healing of the cornea, and improved vision. Reports suggest that the chance of a corneal transplant being rejected after one and two years are lower with DSAEK and another type of corneal transplant known as DMEK, compared to PK.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy

If congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy isn’t managed, it can lead to poor vision development and a form of lazy eye due to blockage (amblyopia). Although treating this at a younger age reduces the risk of developing lazy eye, beginning treatment early could increase the chances of complications such as graft breakdown, suture-induced lazy eye, and more exposure to anesthesia.

Getting a corneal graft can often lead to an eye condition called astigmatism. This risk is highest with a type of corneal graft procedure called PK, and could be severe enough to cause lazy eye. However, DSAEK, another type of corneal graft procedure, is linked with a lower risk of getting astigmatism. On the other hand, some patients with this dystrophy have reported high eye pressure that needed medication and a shift in eye focus after getting DSAEK.

During EK grafting, an eye procedure, there’s a chance of damaging the lens. This can cause a condition known as ‘iatrogenic cataract’ which essentially means a cataract caused by medical treatment. To safeguard the lens during EK, pilocarpine (a type of medication that stimulates certain nerves) is used, which makes the pupil smaller.

Preventing Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy

CHED, or Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy, is a condition that can be passed down through families. If someone has a family history of CHED, it’s suggested that they consider genetic counseling. This can provide them with information and guidance about the potential risk they may have of inheriting the condition.