What is Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease)?

Coats disease is an eye disease that isn’t caused by any known factor (idiopathic). It’s marked by abnormal widening and twisting of blood vessels in the retina (retinal telangiectasia), small balloon-like outpouchings filled with blood (aneurysms), and fluid leakage (exudation). George Coats first mentioned it in 1908 as a disease typically seen in male children’s one eye, associated with retinal fluid leakage and abnormal blood vessels.

Later, Theodor von Leber saw a similar instance with abnormal and aneurysmal blood vessels but without any fluid under the retina. This particular condition was then called Leber multiple miliary aneurysms. It was recognized to be an early form of Coats disease. Following this, Shields and other researchers defined Coats disease as ‘an eye disease with unknown cause, showcasing abnormal blood vessels in the retina, fluid leakage, and often a buildup of liquid in the retina leading to its detachment, without any signs of pull on the retina or vitreous (jelly-like substance filling the eye).’

What Causes Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease)?

Coats disease is a condition that typically happens by chance and usually affects only one eye. This hints at the possibility of it being caused by changes in our body cells.

It shares a trait with other diseases like Norrie disease, familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR), facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD), and osteoporosis pseudoglioma syndrome; all these conditions are associated with problems in the ‘Wnt signaling pathway’ (a complex system of communication within our cells) during ‘retinal angiogenesis’ (formation of new blood vessels in our retina, which is at the back of our eye).

Some researchers found a change in the ‘CRB1 gene’ in 55% of eyes suffering from retinitis pigmentosa (an eye disease that causes loss of vision) and a condition similar to Coats disease. They’ve suggested that the ‘CRB1 gene’ could be involved in Coats disease as well as other eye conditions.

There’ve been several reports suggesting that a small change within the ‘Norrie disease pseudoglioma gene’, NDP, located on the X chromosome (one of the chromosomes that determine our sex) could be linked to the development of Coats disease. Changes in another gene, the ‘PANK2 gene’, have also been suggested as a possible cause of Coats disease.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease)

Morris and his team studied Coats disease in a specific population. They found that the occurrence of this disease was about 0.09 per 100,000 people. In all instances, the disease impacted only one eye, and 85% of the affected individuals were male. Typically, the disease presented itself when a patient was about 146 months old (or about 12 years old), though it could even be present at birth. However, only in 5% of the cases did the disease affect both eyes. As for the other, unaffected eye, it usually displayed no symptoms but had minor changes in the peripheral (outer) areas of the eye. It’s also worth noting that Coats disease can be diagnosed later in life. In a larger study, 7% of the 646 Coats disease patients diagnosed at a specialized eye care center were at least 35 years old at the time of their diagnosis. The average age of diagnosis in these adult-onset cases was 47 years old.

Signs and Symptoms of Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease)

Patients with this condition can experience a range of symptoms, some of which may not be immediately obvious. Common symptoms include reduced vision sharpness, eye misalignment, a white or yellowish glow in the pupil, eye pain, different colored eyes, and uncontrolled eye movements. In some cases, patients don’t show any symptoms and the condition is only discovered during a routine eye exam.

The sharpness of vision in these patients can vary greatly. Some may have near-normal vision, while others may only be able to perceive hand movements or light. Factors that can affect vision include fluid or lipids under the central part of the retina, scar tissue, swelling, a thin layer of fibrous tissue on the surface of the retina, and damage to the optic nerve. In most cases, the front part of the eye appears normal. However, in some patients, certain abnormalities can be observed including cataracts, new blood vessels on the iris, a narrow space in the front part of the eye, swelling of the cornea due to high eye pressure, cholesterol in the front part of the eye, and an unusually large cornea.

- Reduced vision sharpness

- Eye misalignment

- A white or yellowish glow in the pupil

- Eye pain

- Different colored eyes

- Uncontrolled eye movements

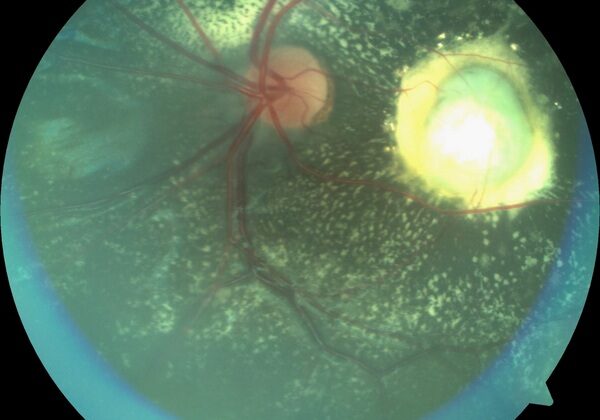

When a doctor examines the retina, they may find dilation and twisting of blood vessels, swellings shaped like a spindle, and fluid build-up within the retina. As the condition progresses, fluid leakage can lead to a detachment of the retina and internal bleeding. Other possible complications include the development of a benign vascular tumor, scar tissue in the central part of the retina, and new blood vessels in the optic nerve. In severe cases, patients may experience inflammation of the iris and ciliary body, develop a cataract, and secondary glaucoma due to new blood vessels, which can eventually lead to a shrunken and disorganized eye.

Adult-onset Coats disease, another form of this condition, often coexists with high blood pressure. It is usually detected incidentally during routine examinations, affects less than half of the retina, typically follows a benign course, and has a better visual outcome compared to the childhood form of the condition. This form of the disease commonly occurs in men and affects one eye in most cases.

Testing for Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease)

Coats disease is typically diagnosed based on clinical signs. However, additional tests are often used when the diagnosis is unclear, especially in cases where there are abnormal retinal changes.

Fundus Fluorescein Angiography (FFA) is one tool that can be used. It provides images of the retina, which is the back of your eye. Typical signs seen on FFA include tiny, widened blood vessels, aneurysms, beaded-looking blood vessel walls, and areas without blood supply in the peripheral (outer) retina. This imaging technique can also help doctors plan treatment by identifying which abnormal blood vessels need laser treatment. New devices, like Retcam and Optos, allow for imaging of the peripheral retina, which is very helpful in diagnosing Coats disease.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) is another imaging tool that can be used. It produces detailed images of the eye’s macula, which is the part of your retina responsible for sharp, central vision. OCT is helpful in detecting if the macula is involved in the disease. It can identify fluid-filled spaces in the macular area, abnormal membranes on the surface of the retina, fluid within or underneath the retina, fats beneath the central part of the retina, and thickness changes in both the central retina and the layer beneath it.

OCT Angiography (OCTA) gives doctors the ability to check how the disease is progressing and how well the treatment is working, without needing any injections. After treatment, OCTA images might show abnormal connections between larger and smaller blood vessels, unusual loops of blood vessels in the central part of the retina or changes in blood flow in the layer beneath the retina. It may also show changes in the part of the retina where there should not be any blood vessels, both in the eye affected by Coats disease and the other eye.

Ocular Ultrasonography (USG) is a test that uses sound waves to produce images of the eye. It shows the extent of retinal detachment, and the characteristics of the space underneath the detached retina. It may also show increased echogenicity (brighter areas on the image) due to cholesterol deposits and can find calcium deposits along the back of the retina, which can occur in advanced Coats disease. Occasionally, analyzing the fluid under the detached retina can also help in diagnosis, by showing cholesterol crystals or certain types of cells.

Two additional imaging tools can be used to differentiate Coats disease from another eye disease called retinoblastoma. The first is a Computed Tomography (CT) scan, which produces detailed images using X-rays. Retinoblastoma would appear as a solid mass with calcium deposits on a CT scan, which would not be seen in Coats disease. The second tool is Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), which uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of the eye. The abnormal retina in Coats disease appears bright on both types of MRI images, whereas in retinoblastoma, it appears bright on one type of image and dark on the other.

Treatment Options for Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease)

The treatment strategy for Coats disease depends on how advanced the disease is. Mild cases, characterized by abnormal blood vessels in the retina but no leakage (exudation), are usually monitored with regular check-ups rather than treated immediately. When leakage does occur, treatment is necessary.

In less severe cases where there’s some leakage, a procedure using a laser, called photocoagulation, can be performed to treat the abnormal blood vessels. The laser treatment can cause some inflammation and a temporary increase in leakage. As a result, multiple laser sessions may be needed, scheduled about 2 to 3 months apart. But for severe cases with a lot of leakage or a detached retina, laser treatment might not work well.

In those situations, cryotherapy (a treatment using very cold temperatures) could be useful. This is done using a method called the double freeze-thaw technique on the affected part of the retina. However, cryotherapy can cause inflammation, discomfort, and sometimes more leakage or even detached retina. Therefore, the treatment has to be split into several sessions to limit these side effects.

For advanced cases where there’s a large amount of leakage near the lens, surgery might be helpful. In these cases, the leaked fluid is drained, and the detached retina is reattached. After that, the retina undergoes a widespread laser treatment or cryotherapy. If the retina is being pulled or torn apart, surgery to remove any scar tissue (pars plana vitrectomy) may be performed, sometimes with additional treatments. The main goal of the surgery is more often to prevent a painful, non-functioning eye and avoid removal of the eye rather than to restore vision.

If the disease reaches an endstage with abnormal blood vessel growth or a specific type of glaucoma, removal of the eye (enucleation) might be necessary. Another option that can be tried in eyes with this specific glaucoma is a treatment called transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation.

In certain cases, it might be helpful to use medications like corticosteroids and anti-VEGF agents injected into the eye. These medications can help reduce the swelling of the macula (the central part of the retina) and leakage. They are often used alongside other treatments, and can also be given before laser or cryotherapy treatments to reduce their associated side effects.

What else can Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease) be?

Coats disease can be mistaken for several other illnesses that exhibit similar symptoms, such as those causing a white or off-white color in the pupil or misalignment of the eyes. These include, but are not limited to:

- Retinoblastoma

- FEVR (Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy)

- Retinal detachment

- Noorie disease

- PHPV (Persistent Hyperplastic Primary Vitreous)

- ROP (Retinopathy of Prematurity)

- Congenital cataract

- Retinal hemorrhage

- Hemangioblastoma

- Toxocariasis

- Choroidal hemangioma

- Coloboma

- Endophthalmitis

- Cytomegalovirus retinitis

- Toxoplasmosis

It’s crucial to differ Coats disease from retinoblastoma, as retinoblastoma is an eye cancer in children which can be fatal if not treated. Some differences should be noted, such as age of onset, family history, colouration in the pupil, and certain ultrasound features.

Furthermore, illnesses like FEVR, Noorie disease, and ROP have specific factors that can help set them apart, such as bilateral presence, family history, and being seen in preterm low birth-weight babies.

Typical features of Coats disease include widened irregular blood vessels, aneurysms, hard exudates, peripheral nonvascular area and fluid-filled retina.

However, it may sometimes be mistaken for other conditions presenting a mass, such as:

- Melanoma

- Papillary or retinal capillary hemangioblastoma

- Choroidal granuloma (caused by sarcoidosis, tuberculosis)

- Vasoproliferative tumor

Similar symptoms can also occur in more conditions, such as:

- Branch retinal venous occlusion

- Vasoproliferative tumor

- Capillary hemangioma

- Chronic retinal detachment

- Trauma

- Inflammation

Coats-like responses might be seen in several other conditions as well, such as Retinitis pigmentosa, Tubercular subretinal abscess, Retinal vasculitis, and many more. Other conditions like Tuberous sclerosis, Alport’s syndrome or Epidermal nevus syndrome, can also exhibit similar responses.

Type I macular telangiectasia also shows some similar symptoms. The Coats-like disease in FSHD (Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy and deafness) appears in a significant percentage of patients, with the retinal involvement being usually bilateral and with mild severity.

What to expect with Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease)

A study conducted by Shields and colleagues observed the impact of Coats’ disease on the vision of 160 patients. It was found that advanced stages of this disease often resulted in poor vision even after undergoing treatment. Advanced cases were less likely to be completely cured, exhibiting continuous signs of the disease such as subretinal fluid and exudation – a leakage of fluid from blood vessels into surrounding tissues.

Furthermore, the need for enucleation, or eye removal surgery, was more common in stage 4 and stage 5 patients. Poor vision in these advanced stages was primarily due to ongoing retinal detachment (when the retina pulls away from its normal position) and macular fibrosis, a type of eye scar tissue.

In the early stages of the disease (stages 1 and 2), the abnormally widened blood vessels (telangiectatic vessels) were seen to entirely or partially resolve within an average of 15 months post-treatment.

Overall, treatment resulted in stable or improved eye structure in around 76% of the cases. However, a small percentage (8%) progressively worsened. About one in five patients needed enucleation due to neovascular glaucoma (a type of eye pressure caused by new blood vessels) or painful phthisis bulbi (a shrunken, non-functional eye).

The risk of Coats’ disease returning remains, even after it appears to have been resolved. Therefore, it is recommended for patients to have lifelong monitoring for any recurrence. Poor vision outcomes are typically indicated by a lack of visual rehabilitation – the process of trying to restore vision to normal – and the presence of fibrotic nodules or scar tissue under the retina.

In a separate group of 67 patients, poor prognostic factors for eye preservation were discovered. These included the presence of a cataract, widespread disease, advanced stage (stage 3B or worse), growth of new tissue along the anterior hyaloid (front part of the vitreous body of the eye), bleeding into the vitreous (clear gel filling the eye), fibrosis either in front of the retina or under the retina, and either combined or tension-caused retinal detachment.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease)

Coats disease, a medical condition affecting the eye, typically progresses over time. When it is active, it can lead to flare-ups, though these are quite uncommon. After these flare-ups, the disease might enter a dormant phase. However, it’s essential to keep in mind that spontaneous recoveries or self-healing is scarce. If left untreated, the disease can cause a series of secondary complications.

Complications may include:

- Orbital cellulitis – a severe eye infection that shares similar signs with retinoblastoma, a type of eye cancer

- Neovascularization – the growth of new blood vessels in the eyes

- Vitreous hemorrhage – bleeding into the clear gel that fills the space between the lens and the retina

- Cataract – cloudiness in the eye lens, leading to blurry vision

- Rubeosis iridis – the abnormal growth of blood vessels on the surface of the iris

- Neovascular glaucoma – a severe form of glaucoma resulting from neovascularization

- Phthisis bulbi – the shrinking or atrophy of the eyeball

Preventing Exudative Retinitis (Coats Disease)

Coats disease is a condition that occurs without a known cause and is not inherited, so there aren’t any steps that family members can take to prevent it. It’s crucial for the patient’s family to understand the future possibilities of the disease, and to know that it’s necessary to keep up with long term checks. The doctor will be sure to explain all of this to the family and patient, so they can plan future care together.