What is Glaucoma?

Glaucoma is a complicated eye problem involving high eye pressure (IOP) that could lead to vision loss over time. It’s the second leading cause of irreversible blindness in the US and is more common in older adults. Glaucoma comes in different forms which can be categorized as either primary or secondary and further divided into open-angle or closed-angle types. In adults, glaucoma usually occurs as primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) or angle-closure glaucoma, including secondary open and angle-closure glaucoma. The main focus, however, is on the most common type, POAG.

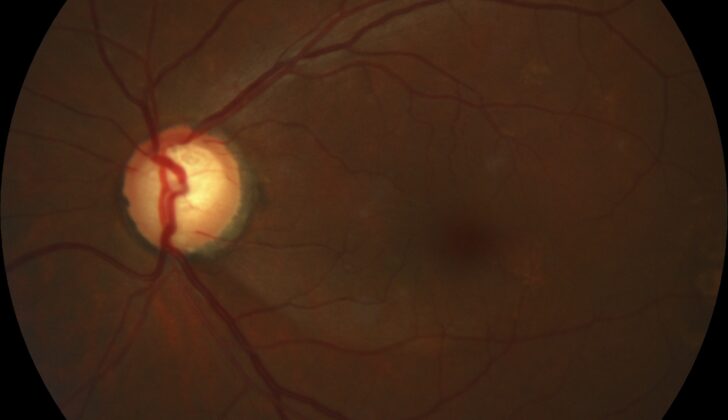

This condition involves the progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells and axons in the optic nerve. This leads to a typical appearance of the optic nerve and a gradual loss of vision. An unusual pattern of peripheral vision loss sets glaucoma apart from other types of eyesight problems.

People with POAG usually don’t show symptoms until there is significant damage to the optic nerve, unless early signs are discovered during routine eye checks. Contrastingly, acute angle-closure glaucoma can occur suddenly and result in quick vision loss, along with symptoms like eye pain, headaches, nausea, and vomiting. Secondary glaucoma often comes from a previous eye injury or other health problems, causing elevated IOP and subsequent optic neuropathy. This group includes several subtypes, such as congenital, pigmentary, neovascular, exfoliative, traumatic, and uveitic glaucoma. In some cases, people can have glaucoma with normal or unremarkable IOP levels, referred to as normal or low-tension glaucoma.

While some types of glaucoma like congenital, infantile, and developmental glaucoma, along with a juvenile variant of POAG, typically affect younger individuals, most types of glaucoma are usually diagnosed in people aged 40 and older. Although high IOP is often linked with glaucoma, a direct relationship has not yet been clearly established. Scientists are exploring genetic and environmental factors that might contribute to the development of glaucoma. Studies involving identical twins, who have similar rates of glaucoma compared to non-identical twins, indicate that environmental factors may also play a key role in the disease’s development.

While current treatments can’t fix optic nerve damage or restore lost vision, they can help manage the disease’s progression through medication, laser treatment, or surgeries to prevent further vision loss. The primary goal of these treatments is to lower IOP and reduce the impact of this vision-threatening condition. They aim to prevent glaucoma in patients at risk and control the condition effectively to limit its progression in affected individuals.

What Causes Glaucoma?

Glaucoma is a condition that is often linked to a high level of pressure in the eye, although the exact cause isn’t known. This high pressure is the main risk factor for developing glaucoma and for the disease to progress. Currently, treatments are able to effectively manage this pressure.

There are several types of glaucoma. One is called Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (POAG), which typically results in slow, painless damage to a part of the eye called the optic nerve. This happens due to problems with draining fluid from the eye. Over time, this results in the pressure in the eye rising, which can cause damage to vision.

Often, those with POAG have high eye pressure readings that line up with damage to the optic nerve and specific patterns of sight loss. As the disease progresses, a slow loss of side vision in one or both eyes can ultimately result in central vision loss.

Although POAG is usually associated with adulthood, it can also affect young people and children. Primary congenital glaucoma is diagnosed in newborns up to 1 month old, infantile glaucoma affects individuals between the ages of 1 and 36 months, and juvenile glaucoma affects those diagnosed between the ages of 3 and 40.

Another type of glaucoma is Low-Tension or Normal-Tension Glaucoma, which is like POAG in terms of optic disc and peripheral vision loss. But the main difference is that this type of glaucoma has normal eye pressure readings, less than 21 mmHg. However, people with this type of glaucoma might have an optic nerve that is unusually sensitive to pressure or experience intermittent pressure changes due to atherosclerosis or vascular insufficiency.

Angle-Closure Glaucoma occurs when the eye’s drainage system is suddenly blocked. This usually happens due to age-related thickening of the lens, which causes a progressive increase in relative pupillary block pushing the iris forward. When sudden pupil dilation occurs, the iris is thick enough or displaced enough to block fluid drainage, resulting in rapid pressure increase within the eye. Though, it’s worth noting that only about 10% of glaucoma cases are acute angle-closure type.

Secondary Open-Angle Glaucoma can come about from different factors such as eye injury, eye disease, and sometimes eye surgery. These conditions can increase eye pressure, which can damage the optic nerve and causes similar functional impairments seen in primary open-angle glaucoma.

Steroid-Induced Glaucoma can happen in individuals vulnerable to the effects of corticosteroids. These steroids can have effects on cells within the trabecular meshwork that increase the resistance to outflow, leading to an increase in eye pressure.

There are many other types of glaucoma caused by various factors, diseases, or conditions, and each of them has distinct characteristics and damages related to eye pressure.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a health issue that gradually causes loss of side vision and irreversible damage to the nerve connecting the eye to the brain. It’s a major health problem because it’s the second leading cause of permanent blindness, following cataracts. Currently, it affects more than 60 million people globally, and this number is expected to exceed 110 million by 2040. The most common type of glaucoma affects 2 to 4% of individuals over 40 years old, and around 10% of those over 75 years old.

People of African descent are most likely to have the most common type of glaucoma, while the Inuit population is most likely to have a type of glaucoma that affects the angle of the eye. Women and people of Asian descent are more likely to be affected in this group. Japanese populations most commonly have a type of glaucoma that involves normal eye pressure.

As you get older, your risk of losing nerve cells in the retina, which is common in all types of glaucoma, increases. Several other factors can increase your risk of developing glaucoma, such as:

- Having a close relative (like a parent, sibling, or child) with glaucoma

- Having other health conditions, like diabetes, high blood pressure, or heart disease

- Experiencing eye trauma

- Having a thinner cornea, which is the clear, front surface of your eye

- Having a history of a detached retina, eye tumors, or eye inflammation

- Using corticosteroids for long periods of time

Signs and Symptoms of Glaucoma

Glaucoma, a disease that affects the eyes, often goes unnoticed in its early stages until picked up during a routine eye exam. Research shows that globally more than half of adults with glaucoma are not aware they have the disease. This is especially the case in Asia and Africa. People with glaucoma usually experience a slow loss of side vision (peripheral) but maintain central vision until the disease has advanced significantly. During a thorough eye exam, certain changes may be detected, such as an enlarged optic nerve, a reduction in peripheral vision, and sometimes, increased eye pressure.

A specific type of glaucoma, normal-tension glaucoma, typically shows no symptoms and the eye pressure reading is normal, thus making it difficult to detect. During an eye check-up, changes in the optic nerve can be seen, such as an enlarged optic disc. A few may also have conditions incompatible with blood clotting (coagulopathies), as well as conditions such as thyroid dysfunction, sleep apnea, or autoimmune or vascular diseases.

Another form of glaucoma, acute angle-closure glaucoma, causes sudden severe eye pain, redness, blurry vision, headache, nausea, and vomiting. Patients often state that they see bright circles around light sources (halos). On checking the eye, the pupil does not respond to light and the eye feels stiff to touch. Eye pressure is normally extremely elevated. Predisposing factors include a shallow anterior chamber depth and a narrow angle between the iris and the cornea. Patients may be advised to avoid medications known to dilate the pupils to lower the risk of a sudden attack.

- Sudden severe eye pain

- Redness

- Blurry vision

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Seeing halos around light sources

- Pupil not responding to light

- Elevated eye pressure

Patients with secondary glaucoma usually have a history of recent eye procedures, trauma, or other health conditions causing abnormal blood vessel formation (neovascularization), such as diabetic eye disease or retinal vascular occlusions. Subtle signs during an eye exam can indicate the cause of increased eye pressure. These signs may include certain material on the front of the lens, pigment deposition on the cells of the cornea, inflammation of the iris or certain signs of trauma.

Testing for Glaucoma

When checking for glaucoma, several different tests and examinations are carried out. These include looking at the back of your eye, checking your field of vision, measuring the pressure in your eye (tonometry), scanning your eye structures (optical coherence tomography or OCT), and examining the front part of your eye (gonioscopy). Of these, checking eye pressure is one of the most critical because high pressure is the biggest risk factor for glaucoma.

The Goldmann applanation tonometry is a commonly used method to check the eye pressure. However, there are other types available when the Goldmann method is not suitable, such as for individuals who are bedridden, uncooperative, children, or those allergic to anesthetic drops.

Other useful tests include checking your ability to see clearly at different distances (visual acuity), measuring the thickness of your cornea (pachymetry), and scanning the back of your eye to monitor for any changes in the nerves in your eye. Regular checks of your whole visual field are also essential, especially for those with risk factors, high eye pressure, or those already being treated for glaucoma. OCT is great for watching for changes in the optic nerve and eye nerve fibers, especially in those with high eye pressure and early to moderate glaucoma.

Glaucoma is typically diagnosed by identifying a gradual loss of optic nerve fibers and/or defects in your field of vision, often along with high eye pressure. People with high pressure in their eyes but without damage to optic nerves or defects in vision are diagnosed with ocular hypertension. About 20% of these individuals may develop glaucoma, which emphasizes why regular testing of eyes, checking the eye pressures and comprehensive exams are key to early detection and treatment to prevent damage to eyes.

There isn’t a single best test for diagnosing glaucoma. More often, glaucoma is detected during routine eye checks as the condition often doesn’t show symptoms or cause vision loss in its early stages. At these checks, doctors look at the optic nerve, check if there are any risk factors and interpret the results of other tests to accurately diagnose and determine the stage of glaucoma. Based on factors like age, family history, and specific risk factors, the American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends specific scheduling for comprehensive eye exams for those with risk factors for glaucoma.

Treatment Options for Glaucoma

Glaucoma treatment is personalized and varies according to the type and severity of the condition. No current treatments can restore lost vision; instead, the goal is to lower eye pressure, a major risk factor, to prevent additional damage and vision loss. Various treatments, including eye drops, laser procedures, and surgeries, aim to reduce this eye pressure. Monitoring of the disease’s progression is done using tools like tonometry, visual field tests, Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), and vision loss mapping.

In the most common form of glaucoma, known as open-angle glaucoma, medications are typically used first to reduce eye pressure. These medications include prostaglandin analogs, beta-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, alpha-2 agonists, miotic agents, Rho-kinase inhibitors, and nitric oxide-donating drugs. Laser-based treatments may also be used sparingly, but these usually have benefits lasting only a few months and retreatments are often needed.

If medications and/or laser treatments don’t work effectively, alternative procedures may be used, such as trabeculectomy, deep sclerectomy, canaloplasty, drainage valve/tube shunt insertion, and laser treatment. A newer type of procedure known as Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) is being increasingly used, particularly in mild-to-moderate glaucoma. Compared to traditional surgery, MIGS believe to be safer, have faster recovery times, and efficiently reduce eye pressure. It can also decrease the need for pressure-lowering medications.

For another specific type of the condition, normal-tension glaucoma, medications including prostaglandin analogs, alpha-2 agonists, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and miotics are typically used, along with treatment for any underlying conditions. Beta-blockers are sometimes used but this is debated due to worries about potentially reduced optic nerve head blood flow. If medication doesn’t work, laser or filtration surgery may be necessary. Studies demonstrated that decreasing eye pressure can slow or halt the progression of vision loss in these patients.

In angle-closure glaucoma, which is considered to be a medical emergency, patients usually need a laser procedure called laser peripheral iridotomy. This procedure relieves the pressure causing the condition by making a small hole in the iris. Medications can be taken to reduce eye pressure quickly. After successfully treating the emergency, it’s important to check the other eye, as there is a high chance that it might also develop the condition in the future. Treatment for secondary glaucoma should focus on dealing with the underlying cause along with taking eye pressure-lowering medications.

What else can Glaucoma be?

If a doctor thinks you may have Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG), they need to make sure that other conditions aren’t responsible for vision problems. These conditions include eye damage from low blood flow (ischemic optic neuropathy), deterioration of the optic nerve (optic atrophy), and pressure on the optic nerve not caused by glaucoma– all these can cause similar visual loss and sometimes result in a condition which looks like a glaucoma-damaged optic nerve.

The doctor may examine your eye pressure or optic nerve and perform a gonioscopy, a test to check the front part of your eye. They also need to watch out for signs of other types of glaucoma, check for any reactions to medication, and review any eye injuries or surgeries you’ve had before.

If your symptoms come on suddenly and look like another form of glaucoma called acute angle-closure glaucoma, the doctor should also consider other possibilities. These could include many conditions such as inflammation of the iris, blood in the front part of the eye after an injury, conjunctivitis, inflammation of the outer layer of the eye, migraines, cluster headaches, spots of bleeding on the eye’s surface, scratch on the surface of the eye, inflammation inside the eye, too much pressure in the eye socket, corneal ulcer, infections around the eye or infectious corneal inflammation. To identify the precise cause, the doctor needs to take a detailed personal history and do a thorough eye examination with a special microscope called a slit-lamp. Based on these findings, the doctor will then arrange for further tests or referrals if necessary.

What to expect with Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a serious condition that, without treatment, can cause permanent loss of vision. The higher the pressure in the eye and the longer the duration of this high pressure, the higher the risk of damage to the optic nerve. Early detection of glaucoma is crucial to minimize this damage. Prompt intervention can also help prevent or slow down the loss of vision. Successful treatment of the disease, especially keeping eye pressure at low levels, can often lead to good results. This includes preserving the range of sight and preventing the disease from getting worse.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Glaucoma

Glaucoma can lead to complications such as loss of vision and could even result in complete blindness. In worst cases, the affected eye may no longer be able to perceive light.

Preventing Glaucoma

A standard eye checkup usually involves measuring the pressure in both eyes. Along with this, there should be regular in-depth checks of the front section of your eyes and an examination of your retina, with special focus on the optic nerve. These early checks are key for identifying people who may be at risk of developing glaucoma.

Those at high-risk might need additional tests, like a visual field examination, OCT (Ocular Coherence Tomography), pachymetry (a method to measure the thickness of your cornea), and gonioscopy (an examination method to study the front part of your eye) to confirm if they have glaucoma.

Patients should be informed about what causes glaucoma, what puts them at risk, and how it can be treated. They need to understand that most times, glaucoma causes a slow and gradual loss of vision that often isn’t noticed until a large part of their field of vision is affected. Therefore, regular eye checkups are strongly encouraged to quickly identify high-risk individuals and to prevent permanent loss of vision.