What is Scleritis?

Scleritis is a serious inflammation condition that affects the sclera, which is the outer layer of your eye. It can be divided into two main types: anterior and posterior, both of which can have different forms such as diffuse, nodular, or necrotizing for the anterior, and diffuse or nodular for the posterior. The impact of scleritis on your vision depends on how severe the condition is, how it presents itself, and whether you have any other health issues. This condition can affect one eye (unilateral) or both eyes (bilateral).

What Causes Scleritis?

Scleritis, or inflammation of the white part of the eye, can happen for unknown reasons or due to infections or other conditions. It can also be linked to cancer, immune system disorders, or be a side effect of surgery or medication. Infections that cause scleritis, such as those from viruses, bacteria, fungi, or parasites, happen in about 4% to 10% of all cases.

Eye cancers and tumors can cause eye inflammation that has the same signs and symptoms as scleritis. Half of people with scleritis will have an immune system disorder, which might not be known at the time they first show signs of scleritis. Arthritis and conditions that cause inflammation in the blood vessels are the most common disorders linked to scleritis.

Scleritis can occur after eye surgeries like removal of a pterygium (a non-cancerous growth on the white part of the eye) or a scleral buckle procedure which places a piece of silicon on the eye to repair a retinal detachment. Some medicines used for osteoporosis, a condition that weakens bones, like bisphosphonates, can cause scleritis, but this is rare.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Scleritis

Scleritis, a condition affecting the eye, is reported in about 10,500 people in the United States each year. This translates to an estimated 4 to 6 cases per every 100,000 people. It typically affects those in middle age, specifically between 47 to 60 years old. Women are more likely to get scleritis, making up about 60% to 74% of the cases. Information about this condition in children is limited, only available through individual case reports.

- There are approximately 10,500 cases of scleritis in the United States each year.

- This amounts to 4 to 6 cases per every 100,000 people.

- Scleritis typically affects people aged 47 to 60.

- Women are more prone to the condition, making up 60% to 74% of the cases.

- Less information is available on the incidence of the condition in children.

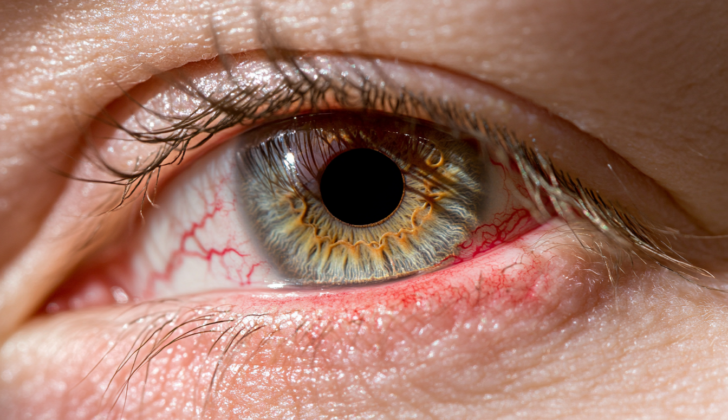

Signs and Symptoms of Scleritis

Scleritis is a condition that can present itself differently based on its location and type., and it can affect one or both eyes.

The symptoms of Anterior Scleritis, which makes up 98% of all cases, are:

- Located in the front of the eye, from the limbus to the rectus muscle insertion

- Mild to moderate pain and tenderness that worsens at night

- Pain when moving the eye

- A blue-violet color of deep eye vessels best seen in daylight

- Sensitivity to light, watery eyes, and probable decreased vision

- Eye vessels do not turn white when applying 2.5% topical phenylephrine

Diffuse Scleritis is the most common type and can present as:

- Widespread swelling of the sclera

- Deep and surface eye vessels appearing congested

- Can be localized or spread over the entire front part of the sclera

Nodular Scleritis presents as:

- Multiple solid, defined and firm lumps

- Swelling of the sclera and congested eye vessels

- Usually localized

Necrotizing scleritis is the most severe form and involves intense inflammation. Symptoms include:

- Intense congestion of eye vessels

- Severe pain

- Most severe form with the worst prognosis

- Possible thinning of the sclera and exposure of the underlying choroid layer

- Inflammation spreading to other parts of the eye such as the cornea, ciliary body, or trabecular meshwork

Necrotizing scleritis without inflammation or Scleromalacia perforans, is characterised by:

- Significant thinning of sclera with visible choroid layer

- Can be symptomless or may present with decreased visual acuity due to corneal astigmatism caused by the scleral thinning

Posterior Scleritis, which occurs in 2% of cases, can be identified by the following:

- Located behind the insertion of the rectus muscles

- May occur alongside anterior scleritis

- May cause decreased vision, with or without eye pain

- Retinal detachments, optic nerve swelling, and cotton wools spots may be seen on a dilated examination

- A B-scan ultrasound may reveal thickening of the posterior sclera, retrobulbar thickening and fluid surrounding the optic nerve, presenting a characteristic “T” sign

- With the diffuse subtype, there’s a general thickening of sclera and choroid

- In the nodular subtype, scleral nodules can be seen on a B-scan

Testing for Scleritis

To diagnose your condition, your doctor will rely on a combination of your symptoms, a detailed examination of your eyes, your overall medical history, lab tests, and imaging studies.

The laboratory tests typically include different types of blood tests that check for markers of specific diseases:

- Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) – these are often present if you have a condition known as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, previously referred to as Wegener’s granulomatosis.

- Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA) – these could suggest that you have systemic lupus erythematosus or another autoimmune condition.

- Complete blood count(CBC) with differential – this could help identify if your body is fighting an infection or inflammation.

- C-reactive protein – a protein that increases in your blood when there’s inflammation in your body.

- ESR – an indicator of inflammation or infection in your body, which can suggest conditions like giant cell arteritis.

- HLA-B27 – a specific protein that’s more common in people with uveitis, a type of eye inflammation, and has a rare association with scleritis, another eye condition.

- Lyme serology – a test that helps rule out Lyme Disease, which can present with recurrent diffuse anterior scleritis, a specific type of eye condition.

- Rheumatoid factor – indicative of rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disorder.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) – levels could suggest a condition called sarcoidosis.

- Serum lysozyme – another indicator of sarcoidosis.

- Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS) – sign for syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection.

Imaging tests might also be used to get a clearer picture of what’s happening inside your body. This could include:

- Chest X-Ray – to check for signs of sarcoidosis.

- B-scan – this is an ultrasound of the eye, which can provide further details about the posterior part of your eye in cases of posterior scleritis, an inflammatory eye condition.

- MRI – if the above imaging tests don’t give clear results, your doctor may recommend an MRI.

- CT – it can be used if you can’t have an MRI.

- Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) – can help differentiate between episcleritis and scleritis, two different types of eye inflammation.

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT) – it can visualize thickened sclera on the front part of your eye and thickened choroidal tissue.

- Anterior segment fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) – it can help visualize if there is any tissue death in your eye.

Treatment Options for Scleritis

When dealing with scleritis, a condition that causes severe eye redness and pain, the treatment plan targets various goals. This includes identifying what’s causing the condition, managing the inflammation and pain in the eye, alleviating symptoms, preventing any harmful consequences, and trying to prevent future episodes.

If the scleritis is anterior (at the front of the eye) and caused by an infection, the treatment will be custom to the specific infecting agent. In non-infectious cases, the treatment plan is tiered, depending on the severity of the condition:

Firstly, mild cases may be treated with eye drops that contain corticosteroids or with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), taken orally. Corticosteroid eye drops help reduce inflammation, but don’t always work effectively for everyone. NSAIDs are common medications that can reduce symptoms like pain and inflammation. Examples of oral NSAIDs include indomethacin, ibuprofen, and naproxen.

If the first-line treatments aren’t effective, the second approach would be oral corticosteroids, like prednisone, or subconjunctival corticosteroid injections. Injected corticosteroids can also be used when oral options aren’t suitable, although their use has been contentious due to concerns about potential harm to the sclera (the white part of the eye).

In more severe cases, where the corticosteroids aren’t working or could have harmful side effects, the third step would involve immunosuppressive agents. These medications inhibit the immune system to reduce inflammation. Methotrexate is often used, but other options like azathioprine, mycophenolate, and cyclophosphamide could also be prescribed.

Lastly, if all the previous treatments aren’t effective enough or suitable, doctors might recommend the use of biologics. These types of medicines are still being studied for their effectiveness in treating scleritis.

For posterior scleritis, which affects the back of the eye, the treatment begins similarly with oral NSAIDs. If these are ineffective, oral corticosteroids may be used. For more severe cases, immunosuppressive or antimetabolite agents may be used, and biologic medicines may be considered as a final approach. The treatment steps are similar to the anterior non-infectious scleritis, but the need for treatment is more urgent because of the area affected.

What else can Scleritis be?

The main condition that can be confused with scleritis (inflammation of the white outer part of the eye) is episcleritis. Episcleritis is when there’s inflammation in the external layers of the eye tissue and blood vessels. When someone has episcleritis, they might experience mild pain, redness in the eye, a feeling like there’s something in their eye, and tearing. If a doctor puts a 2.5% solution of a drug called phenylephrine into the affected eye, the blood vessels will become less red and noticeable with episcleritis, but this won’t happen with scleritis. Most of the time, episcleritis comes on by itself and gets better even without treatment.

What to expect with Scleritis

The outlook for eyesight is generally good for patients with mild or moderate scleritis, which is an inflammation of the sclera or the white part of the eye, if they respond well to the given medical treatment. It’s important as well to manage any underlying health conditions that could be causing this issue.

However, if the patient has necrotizing or posterior scleritis, their risk of losing vision is higher. Necrotizing scleritis is a severe form of the condition involves death of tissues, while posterior scleritis affects the back of the eye. The extent of the inflammation and how it affects other parts of the eye contributes to this risk.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Scleritis

The aftereffects of scleritis, an inflammation of the white part of the eye, can differ based on how severe the condition is and if there are any related autoimmune diseases. These effects can range from reduced vision and cataracts, high pressure within the eye, thinning or dissolving of the sclera (the white part of your eye), and thinning of the cornea (the clear, front surface of the eye).

- Decreased vision

- Cataracts

- Increased pressure inside the eye

- Thinning or melting of the sclera

- Thinning of the cornea

Preventing Scleritis

It’s crucial for people with scleritis, an inflammation of the eye, to understand that they may also be at risk for other health conditions. The key to recovering your vision and improving your overall outcome is to focus on effective pain management and reducing inflammation. This discussion should happen with your healthcare provider, who can guide you through this process.