What is Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis?

Toxoplasma gondii is likely the most common cause of retinochoroiditis, an infection in the eye, around the world. This parasite usually shows itself to eye doctors as quiet, healed scars in the back of the eye during its inactive phase, and as a destructive inflammation of the same area with floating debris inside the eye during its active phase. Though it’s less frequent, the optic nerve, which is responsible for transferring visual information from the eye to the brain, can also be affected. Alarmingly, 25% of patients with a history of retinochoroiditis caused by Toxoplasma have reported having a vision worse than 20/200 (a level considered legally blind) in at least one eye.

What Causes Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis?

Toxoplasmosis is an illness caused by a small parasite (a type of microbe that needs other cells to live and reproduce) called T. gondii. You can catch this by eating food that has been contaminated with the feces of a cat, or by eating raw or undercooked meat.

After you are exposed, the parasite matures in your intestines. It releases smaller parasites called sporozoites that change into another form, tachyzoites. If you eat tissue cysts in the meat (small protective sacs holding dormant parasites, called bradyzoites), these also change into tachyzoites in your intestines.

The tachyzoites then move through deep layers of your intestine walls and get carried to organs like your brain, eyes, liver, spleen (an organ that filters blood), lymph nodes (which are part of your immune system), heart, muscles, and placenta (if you’re pregnant) through your bloodstream and lymphatic stream (a system of vessels that transport fluids around the body). Certain cells in your immune system help the parasite get into your brain and eyes.

If a woman gets infected within 6 months before she gets pregnant, the parasite can pass to her baby and cause congenital toxoplasmosis (a severe disease that can affect the baby’s brain, eyes, and other organs).

Tachyzoites can infect a lot of different kinds of cells in your body. Inside your cells, T. gondii forms a special sac where it hides from the cells that would normally destroy it, while it multiplies quickly. This causes your cells to break and allows infection of new cells.

Eventually, tachyzoites change into a sleeping form, bradyzoite, and form tissue cysts. There are three types of T. gondii. Type I is the most harmful, while types II and III are less harmful.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis

It’s estimated that about one-third of the world’s population is infected by a parasite called T. gondii. This parasite is more common in hot, humid climates like Central America, Asia, and the Caribbean. But it’s also common in more temperate climates – for example, France has some of the highest rates of this infection. The risk factors for becoming infected can vary depending on where you live, your diet, your habits, the prevalence of animals that carry the parasite, and the climate.

- In the United States, between 20% to 70% of people have been infected by this parasite.

- About 0.6% develop a type of eye infection called Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis.

- If a woman gets infected with this parasite within 6 months before getting pregnant, there’s about a one-third chance it will be passed on to the baby.

- This infection in newborns – called congenital toxoplasmosis – occurs in about 1 out of every 1,000 to 10,000 live births in the United States.

- In most cases, babies with this condition will have scarring on both retinas.

Signs and Symptoms of Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis

TRC, also known as Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis, is a condition that may lead to symptoms such as sudden appearance of “floaters” in your vision, loss of sight, blurry vision, eye pain or sensitivity to light. However, in some cases, small active lesions in the peripheral parts of your vision may not cause any symptoms at all. There are usually no signs of this condition showing up in the body, but if present, they can mimic flu-like symptoms such as fever, swollen lymph nodes, and generally feeling unwell. For people with weakened immune systems, they may experience toxoplastic encephalitis, which is a brain infection that comes with new neurological issues or a brain abscess. It’s interesting to note that in autopsies of patients with HIV/AIDS, cerebral toxoplasmosis has been found in 10% to 34% of cases.

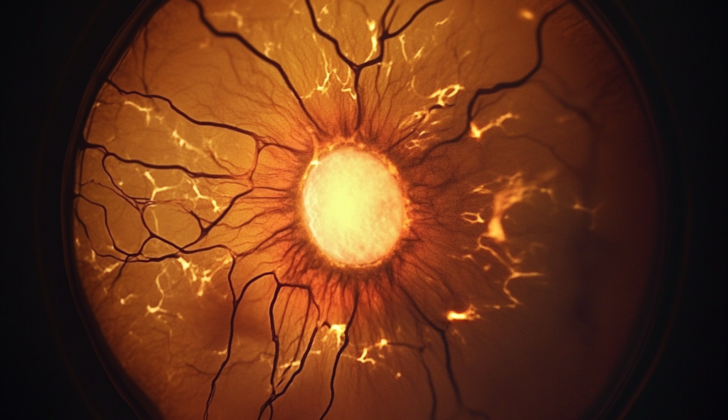

Toxoplasma can cause damage to the back of the eye, appearing as a yellow-white lesion with blurred edges and a clouded vitreous fluid in the eye (described as “a headlight in the fog”). It’s often found next to an old scar at the back of the eye. In some cases, the Toxoplasma can cause a localized inflammation around small arteries in the affected area. Older pigmented lesions may be clustered or appear in strings. In cases where toxoplasmosis was present from birth, it often appears as a large scar at the back of the eye. This can sadly often be in the central part of the retina (the macula) and have been described as a “macular coloboma.” While there is debate regarding how often TRC is acquired versus inherited from birth, it is thought that those cases present from birth usually affect both eyes, while those acquired later usually only affect one eye.

TRC in people with weakened immune systems may be so severe that it mimics a condition called acute retinal necrosis, which has multiple merging lesions on the periphery of the retina. If the lesion is close to the optic nerve, inflammation of the optic nerve head and retinal inflammation can occur. Issues related to inflammation inside the eyeball due to TRC include long-lasting opacity of the vitreous, bands within the vitreous connecting to the optic nerve, cystic swelling of the macula, cataract, and also findings in the front part of the eye that include adhesions between the iris and lens, and an inflammatory form of glaucoma. Patients who were born with TRC can also have microphthalmia (small eyes), nystagmus (rapid involuntary movements of the eyes), and strabismus (misalignment of the eyes), among the ocular findings.

For those born with systemic toxoplasmosis, the mother usually exhibits milder symptoms similar to mononucleosis, or shows no signs of illness, while the newborn baby may show symptoms of being born early, slow growth while in the womb, jaundice, enlarged liver and spleen, heart inflammation, pneumonia, various skin rashes, and nervous system issues that include inflammation at the back of the eye, buildup of fluid in the brain causing increased pressure (hydrocephalus), mineral deposits in the brain, smaller than normal head size, and seizures. Some of these neurological issues may only become noticeable after several months or years. The classic presentation of these neurological findings is inflammation at the back of the eye, hydrocephalus, and mineral deposits in the brain.

In people with normal immune systems, such as pregnant mothers, toxoplasmosis is often mild and may not be recognized. Moreover, in patients with weakened immunity, like those suffering from AIDS or on immunosuppressive therapy, they could experience severe damage to the back of the eye that could resemble acute retinal necrosis, forwhich brain imaging is crucial. Up to a third of AIDS patients with retinal findings have been reported to have toxoplasmosis of the central nervous system. They typically require aggressive and long-lasting suppressive therapy with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine.

Testing for Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) Scanning

The OCT scan is a type of eye examination that helps your doctor identify problems such as a thin layer on the surface of the retina (epiretinal membrane), swelling and fluid in the retina (cystoid macular edema), tension between the retina and the vitreous gel in the eye (vitreoretinal traction), and fluid-filled areas under the retina (serous retinal detachments). In cases of active eye infection (TRC), the OCT displays a bright signal that can hide the underlying blood vessels. One more thing your doctor can notice is that a transparent layer of the eye called the hyaloid is usually thickened and detached from the eye’s innermost layer over the infection area.

Fluorescein and Indocyanine Green Angiography

Fluorescein angiography (FA) and Indocyanine green (ICG) are both methods used to visualize blood vessels in your eyes. In an active TRC infection, your doctor will see early intense brightness with FA, followed by progressive intensity. Similarly, with ICG, the early stages show less brightness. ICG can reveal less bright, satellite lesions that cannot be detected by FA or routine examinations. The less brightness is thought to be due to a noninfectious inflammatory reaction. ICG can also show areas of reduced blood supply in the choroid (the blood vessel layer of the eye) along with retinal detachments filled with fluid.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound of the eye becomes necessary when inflammation in the eye’s gel (vitreous) makes it hard to clearly view the retina. This technique can display certain features associated with TRC, such as tiny echoes within the eye’s gel and thickening of the hyaloid layer. Detachment of the gel from the retina and focal thickening of the retina-choroid layers are also commonly seen.

Vitreous or Aqueous Sample

In unusual cases, a sample from the eye’s fluids (either the vitreous or aqueous) may be required. Tests on these samples can detect antibodies against Toxoplasma, the causative agent of TRC. The presence of a certain ratio (8:1) between antibodies in the eye and the blood can indicate active ocular toxoplasmosis, an infection of the eye caused by Toxoplasma.

Treatment Options for Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis

Eye lesions that are not close to the optic nerve or the macula, and hence less likely to impact vision, generally do not require treatment. Treatment is usually recommended when a lesion is located close to the center of the fovea or the margins of the optic disc, the areas critical for vision.

A recent study comparing different treatments found no significant difference in visual outcomes for patients with healthy immune systems who have acute Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis, a specific condition affecting the retina and choroid in the eye. However, in patients with chronic, relapsing TRC, treatment may help prevent further episodes. Nevertheless, treatment is usually initiated in patients who have lesions close to the optic nerve or macula and whose vision is significantly restricted. This decision is taken after careful consideration as studies have shown that over a quarter of patients experience side effects from the medication used in treatment. Additional caution is needed when treating pregnant patients due to potential impact on the fetus.

While no universally accepted treatment for TRC exists, the “classic therapy” which has been used for over 50 years includes a combination of oral medications. These include pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid, along with a high-dose of prednisone. However, these medicines have specific risks and cannot be prescribed to all patients. For example, sulfadiazine cannot be used in those with sulfa allergies.

Several other medications including clindamycin, spiramycin, azithromycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and atovaquone have been tried in various combinations. Some of these may be beneficial for patients and carry a significantly reduced risk of side effects.

Set alongside these medicines, the use of adjuvant steroids, while traditionally part of the TRC treatment, has not been conclusively proven to be beneficial and it depends on the patient’s specific condition.

Some patients have been treated with medications injected directly into the eye. However, it’s essential to note that treatment with steroid injections alone usually leads to extensive retinitis, a condition where the retina becomes inflamed.

Also, while certain treatments like barrier laser and other medications have not been successful in reducing the recurrence rate of TRC, long-term use of a medication called trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has shown to significantly reduce the likelihood of recurrence of TRC.

Less than 2% of patients with HIV are diagnosed with TRC. Elderly patients and individuals with weakened immune systems have a higher risk of developing a severe form of retinochoroiditis. In such cases, treatment includes long-term suppressive therapy.

What else can Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis be?

When a patient shows signs of TRC (The Retinal Connection), a condition affecting the back of the eye, doctors must consider a range of possible causes. These include various infectious and inflammatory diseases such as:

- Tuberculosis

- HIV retinitis (an HIV-associated eye condition)

- Toxocariasis (an infection caused by roundworms)

- Sarcoidosis (a disease that leads to inflammation in various body parts)

- Syphilis

- Cytomegalovirus retinitis (another eye condition often seen in people with weakened immune systems)

- Candida endophthalmitis (a fungal infection in the eye)

- Multifocal choroiditis (an inflammatory condition affecting parts of the eye)

- Serpiginous choroiditis (a rare eye condition causing loss of vision)

- Presumed ocular histoplasmosis (a condition where fungus can lead to vision loss)

- Acute retinal necrosis (a serious viral infection of the retina, the inner back layer of the eye)

What to expect with Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis

If someone has had a Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis (TRC) infection, it’s more common for it to reappear particularly in children and teenagers, most often within a few years from the first infection. After the first few years, the chance of it reappearing gradually goes down. One study found that out of those with a past TRC infection, about half had it come back within 3 years and 80% within 5 years. On average, a person may experience this reoccurrence about 2.7 times in their lifetime.

Preventing Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis

Places where cats frequently visit, like sand or dirt in gardens or playgrounds, as well as their litter boxes, can pose a high risk to health. It’s advisable to stay away from these areas if possible. We recommend that you regularly clean your fruits and vegetables. Washing your hands after touching soil or cat litter boxes is also a good practice.

Toxoplasma cysts, which are tiny forms of parasites that can cause infection, can be killed by subjecting them to a temperature of 60 degrees Celsius for 15 minutes or freezing them at -20 degrees Celsius for at least 24 hours. So, it’s important to ensure your food is properly cooked or frozen to eliminate this health risk.

Drinking water that has been contaminated with oocysts, another form of these parasites, is a common way for people to acquire toxoplasmosis – a disease caused by parasites. This is particularly true in areas where water treatment is not sufficiently managed.