What is Brain Cavernous Angiomas (cavernous malformations)?

Cavernous angiomas, also known as cavernous malformations, cavernous hemangiomas, or cavernomas, are a type of abnormal blood vessel formation in the brain, which originates from early development issues. Although ‘haemangioma’ and ‘cavernoma’ are sometimes used to describe these, they don’t accurately represent what they are because these issues aren’t tumors.

These abnormal vessel formations can occur in every part of the body and fall into four main categories, based on what they look like and their physical features:

- Capillary malformations, also known as telangiectasias

- Cavernous malformations, also known as cavernous angiomas or hemangiomas

- Venous malformations

- Arteriovenous shunting malformations

All these kinds of malformations can affect the brain with various symptoms.

What Causes Brain Cavernous Angiomas (cavernous malformations)?

Cavernous angiomas, which are abnormal blood vessels in the brain or spinal cord, can occur randomly or they may be inherited in a family. These unusual blood vessels can be discovered through repeated MRI scans, especially in families who are genetically more prone to develop them.

There is strong evidence showing that cavernous angiomas can develop over time, as seen in the number of new cases that appear after brain biopsies and after certain types of surgery that involve directing radiation at the brain.

It’s noteworthy that in cases where cavernous angiomas run in families, the pattern of inheritance is typically “autosomal dominant”. This means that you only need to inherit the gene from one parent in order for you to have the condition, but not everyone who inherits the gene will develop symptoms–a situation known as “incomplete penetrance”.

Scientific studies have identified three genetic locations (CCM1, CCM2 and CCM3) which can hold faulty genes responsible for causing brain cavernous malformations in families.

In a significant number of familial cases among Hispanic Americans and non-Hispanic Families, these faulty genes have been traced back to mutations in the CCM1 gene located on chromosome 7 and CCM2 and CCM3 located at 7p and 3q respectively.

In addition, some scientists believe in the theory of a “second hit mutation”. This theory suggests that initially, inheriting or acquiring one faulty gene doesn’t cause the disease by itself, but if a second mutation strikes the same gene, it will trigger the onset of the disease.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Brain Cavernous Angiomas (cavernous malformations)

Cavernous angiomas of the brain and spinal cord can happen at any age, but they often show symptoms between the ages of 30 and 60. Both men and women can be affected, as there’s no genetic predisposition tied to gender. Cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM), a specific type of cavernous angioma, is found in about 0.5% of people. However, only 40% of these cases show symptoms. If a cavernous angioma occurs on its own, it’s usually just one and it typically doesn’t cause any symptoms. But if it’s part of a family pattern, there can be multiple, and they’re more likely to cause symptoms. This is why it’s recommended for family members to get checked out. Most cases of CCMs are diagnosed in adults, but they’re also found in about 25% of children.

- Cavernous angiomas can happen in the brain and spinal cord at any age but often show symptoms between the ages of 30 and 60.

- Both men and women can have this condition as there is no genetic predisposition based on gender.

- About 0.5% of the population has a specific form of this condition, known as cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM).

- However, only 40% of CCM cases show symptoms.

- When the angioma occurs on its own, it’s usually a single lesion and tends not to cause symptoms.

- If a family pattern of CCMs exists, the presence of multiple malformations is common and these are more likely to cause symptoms.

- Because of this, family members are advised to get checked.

- Most of the cases are diagnosed in adults but 25% of cases show up in children too.

- When an individual has multiple lesions, usually 5 or more, they may experience seizures and/or focal neurological deficits due to recurrent hemorrhages.

Signs and Symptoms of Brain Cavernous Angiomas (cavernous malformations)

Cavernous malformations (CMs) are abnormal collections of blood vessels that can cause various symptoms or remain unnoticed for a lifetime. Symptoms may include headaches, seizures, or neurological deficits due to bleeding. It’s important to note that the risk of bleeding is higher in individuals with a family history of CMs, and those associated with developmental venous anomalies (DVAs) or unusual venous drainage.

The symptoms and impact of CMs largely depend on their location within the brain:

- Supratentorial CMs, which are located on the top part of the brain, often result in bleeding, seizures, and neurological deficits. The cause of these symptoms might be due to the mass effect on surrounding tissues, changes in microcirculation, or small-scale bleeding irritating the brain tissue. Research suggests an annual bleeding rate of 0.25-1.1% for these types of CMs.

- Infratentorial CMs, found at the lower section of the brain, typically lead to recurrent bleeding and continuous neurological deficits. Specific symptoms include cranial neuropathies when the CMs are located in the brain stem. This is due to the presence of cranial nerve nuclei and their fiber tracts in the brain stem. The annual bleeding rate for these types of CMs is 2-3%, with a recurring bleed rate of 17-21%.

Location-wise, 70-90% of lesions are found in the cerebrum, particularly in the rolandic and temporal areas. About 25% of all cranial cavernous malformations include posterior fossa lesions, primarily in the pons and cerebellar hemispheres.

Testing for Brain Cavernous Angiomas (cavernous malformations)

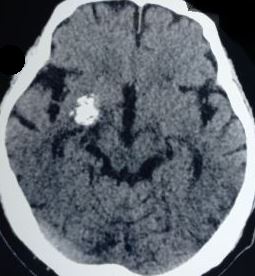

Imaging tests like MRI and CT scans play a key role in diagnosing brain conditions like cerebral cavernous angiomas. An angioma is a cluster of abnormal blood vessels.

For this condition, MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) is typically the first option. In an MRI, images of the brain are created using a large magnet and radio waves. The images reveal smoothly outlined lesions (problems in the brain tissues) with patterned signals of different strengths, consistent with bleeding in different stages.

The MRI can also make it easy to notice even minor or recent bleeds in the brain. MRI images can also show how the lesions react after being applied with contrast agents, a special dye that helps doctors see the structures better. This information is important for doctors to plan surgical procedures effectively.

On the other hand, CT (Computed Tomography) scans are not used as frequently for diagnosis due to their slightly lower specificity, or their ability to accurately identify the condition. In a CT scan, a series of X-rays are taken from different angles and assembled into a detailed image by the computer. If cavernomas are spotted in a CT scan, they typically appear as small, oval or rounded problem areas with increased density.

However, the scan may not always show clear changes to the surrounding brain tissues unless recent bleeding occurred. The CT scan can show if the cavernomas have calcified, turned into harden masses due to calcium buildup, in about a third of cases. If there is bleeding, surrounding edema, or swelling, can be noted. Older lesions can include areas or cavities that are less dense and do not increase in density after contrast agent use due to reabsorbed old blood clots.

Patients, particularly young ones, who have recently experienced bleeding in the brain might have cavernous angiomas as a potential cause. It’s also worth considering in patients with seizure disorders, especially those between 20 and 40 years old. These details are very important as cavernomas can cause seizures and need to be identified and managed accordingly.

Treatment Options for Brain Cavernous Angiomas (cavernous malformations)

If a person has asymptomatic cavernomas (blood vessels malformations in the brain), doctors usually observe a conservative approach. This approach means doctors carefully monitor the condition without taking immediate action unless necessary. Doctors use routine MRI scans to watch for changes in the lesion – the abnormal blood vessels. They’ll continue this approach as long as the cavernoma remains stable – no changes in size, no new symptoms, and no signs of bleeding.

Most cavernomas are found above the tentorium (a membrane in the brain) and are called “supratentorial.” Doctors might consider removing these cavernomas through surgery if the patient is continuously getting worse, experiences hard-to-control seizures, or if there is a single case of bleeding. Especially if the cavernoma is in an area of the brain that doesn’t control vital functions, it can often be removed without causing significant problems. Surgeons might also consider removing the cavernoma if there are repeated bleeds in important areas of the brain that result in worsening symptoms. Other reasons for surgery could be serious symptoms like heart or breathing instability or if the cavernoma is too close to the surface of the brain.

Several studies have reported that surgical outcomes for removing cavernomas in the brain and cerebellum can be very good. Using advanced techniques like precision imaging can significantly reduce the risk of surgery-related complications.

It can be more difficult to manage cavernomas that are located in the brain stem because this area houses many important nerves. Any additional mass or fluid can press on these nerves and disrupt essential involuntary functions like breathing or heartbeat. Surgeons might consider removing these types of cavernomas in certain situations – such as if the cavernoma is on the surface of the brain stem, repeated bleeding is causing worsening symptoms, blood from the cavernoma is affecting the surrounding brain tissue, or the growth of the cavernoma is pressing on the surrounding tissue.

To manage this, patients are often treated with steroids before surgery to reduce swelling. Also, if there’s an abnormal vein associated with the cavernoma, surgeons try to avoid removing it because of the risk of causing a harmful clot.

During surgery, the aim is to remove all of the cavernoma, including a substance called hemosiderin – a byproduct of blood breakdown which may be found around the cavernoma – to prevent further bleeding and achieve complete control of seizures. Doctors usually do a follow-up MRI within 72 hours after surgery to check for any bleeding, which may require another operation.

If there’s a long history of seizures before the surgery and if the seizures are not easily controlled, these can be signs that the outcome might not be as good. Stereotactic radiosurgery, a form of radiation therapy, might be an alternative for patients with cavernomas that are hard to reach with surgery. However, some studies have reported potential risks with this approach, such as the chance of repeated bleeding, permanent neurological deficits, and side effects from radiation.

What else can Brain Cavernous Angiomas (cavernous malformations) be?

There are several conditions which can be confused with or have similar symptoms. These include:

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Chronic hypertensive encephalopathy

- Diffuse axonal injury (DAI)

- Cerebral vasculitis

- Radiation-induced vasculopathy

- Hemorrhagic metastases

- Hemorrhagic primary brain tumours

- Parry-Romberg syndrome

These conditions will require appropriate medical examination to differentiate and make an accurate diagnosis.