What is Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy?

Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FED) is an eye condition that affects both eyes, progressing slowly, often at different rates. The hallmark of this condition is the deterioration of the innermost layer of the cells (endothelial cells) in the cornea and the development of ‘guttata.’ These are tiny bumps or growths on the inner support layer of the cornea, known as Descemet’s membrane.

As FED advances, more and more endothelial cells are lost, leading to a reduction of the cornea’s natural ability to pump water out. This causes swelling or edema in the cornea, which can affect the outermost layer (epithelium) or the thick middle layer (stroma). The result of this is eye pain, glare, halos around lights, and decreased vision clarity. FED is the most common corneal condition that can damage the endothelium and frequently requires surgical treatment around the world.

The major difference between a related condition known as “cornea guttata” and FED is the presence of corneal swelling in the later. It is worth mentioning that there is a variant of Fuchs dystrophy in which the patient gets corneal swelling without the growth of ‘guttata.’ Still, this type of FED is rare, and information about it isn’t as widely available.

The condition now known as Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy was first identified in 1910 by Ernst Fuchs, an eye specialist from Vienna. He noticed the central clouding of the cornea in 13 elderly patients. Over the years, significant studies have been done on the ‘guttata’ and their relation to FED. Further research is still needed to fully understand why and how the disease progresses. Over the past 20 years, much progress has been made in managing FED, which has improved the quality of life for those living with the condition.

What Causes Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy?

FED, or Fuchs’ Endothelial Dystrophy, is a genetic condition that usually occurs in a pattern known as autosomal dominant inheritance. This means that you only need to get the disease gene from one parent to inherit the disease. Still, how this gene expresses and causes symptoms can vary, and not everyone who has the disease gene shows symptoms, a trait known as ‘incomplete penetrance’. Interestingly, in nearly half of the FED cases, there’s no family history of the disease.

There are several factors linked to FED that make its development quite complex. ‘Early-onset FED’ – the form of disease that starts at a young age – is heavily influenced by genetic factors. It often runs in families and is usually caused by a mutation in a gene called COL8A. This mutation affects your eye’s Descemet’s membrane, which is an important part of your cornea (the clear front cover of your eye).

The ‘late-onset FED’, or the form of the disease that develops later in life, is associated with different genetic mutations. This makes it more genetically diverse than the early-onset form. Some of these mutations occur in genes like TCF4, DMPK, and SLC4A11. The mutation in the TCF4 gene is particularly common in Caucasians.

The SLC4A11 gene is important as it helps regulate the movement of water in the cornea, maintaining its clarity. Mutations in this gene can lead to corneal swelling, a common symptom of FED. Similarly, other genes like ZEB1, AGBL1, and LOXHD1 have been linked with FED.

It’s noteworthy that some genetic changes causing FED can also lead to other similar conditions, such as posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPMD) and congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED). This certainly makes understanding and diagnosing these conditions quite challenging.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy

Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (FED) is a condition that presents some diagnostic challenges. Many patients develop corneal guttata, a specific eye symptom, which doesn’t always lead to FED. Often, symptoms of FED only become noticeable after many years. The first signs are typically corneal guttata, usually first seen in a person’s forties. However, it’s often not until their sixties or seventies that they require surgery. Data shows that FED is the primary reason for corneal-endothelial transplants around the world.

While up to 4% of people over the age of 40 in the U.S. may show signs of guttata, it doesn’t always come with another symptom, corneal edema. Therefore, many of these patients with guttata do not get diagnosed with FED. Studies show varying incidences and prevalence. One study in Iceland found 11% of women and 7% of men had primary corneal guttata. Similar studies in Singapore and Japan showed 6.7% and 3.7% of people having the same symptom. The incidence of central corneal guttata was found in 31% of eyes from 20 to 39 years of age, and in 70% of eyes over 40.

Estimates regarding the incidence and prevalence vary greatly, likely due to differing clinical definitions of guttata. There is some evidence to suggest that FED might have a higher prevalence in Europe compared to other regions, and Europe and the U.S. tend to have higher numbers of patients getting transplants due to FED. Meanwhile, lower rates of FED are seen among Asians.

- Risk factors for FED that aren’t inheritable include age, gender, smoking, exposure to UV light, and diabetes, with people over the age of 40 and women having higher risks.

- The female to male ratio for FED is roughly around 2.5:1 to 3:1.

- There is also a rare early-onset form of FED that appears in the first decade of life where the female to male ratio is 1:1.

Signs and Symptoms of Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy

Fuchs’ Endothelial Dystrophy (FED) is a condition that usually starts showing symptoms around a person’s forties. The progression of the disease is divided into four stages spanning 20 to 30 years. During the early stages, many people with FED might not experience any symptoms. Routine eye examinations might reveal minor changes in the eye, like the appearance of guttata, small droplets on the cornea, but these don’t cause any noticeable vision changes.

The stages of FED progress as follows:

- Stage 1: Some people might have guttata in the central cornea. These signs are often overlooked as they resemble normal changes in the eye, and they are only identified when the disease progresses into later stages.

- Stage 2: Corneal edema, or swelling of the cornea, develops. Patients might complain of blurred vision and glare that is worse in the mornings. This can be due to increased hydration of the cornea overnight from closed eyelids. Other complaints may include needing to change glasses multiple times a day due to a shift in vision, hazy cornea, poor night vision, and pain when blinking.

- Stage 3: The surface of the cornea might show “bullae,” or small fluid-filled blisters, causing further vision deterioration. These blisters can burst, causing discomfort or pain.

- Stage 4: Significant vision loss occurs due to subepithelial scarring. Severe cases might only be able to distinguish hand motions in front of them. Extreme discomfort or pain may be absent at this stage; this stage is rare in developed countries due to the availability of corneal transplants.

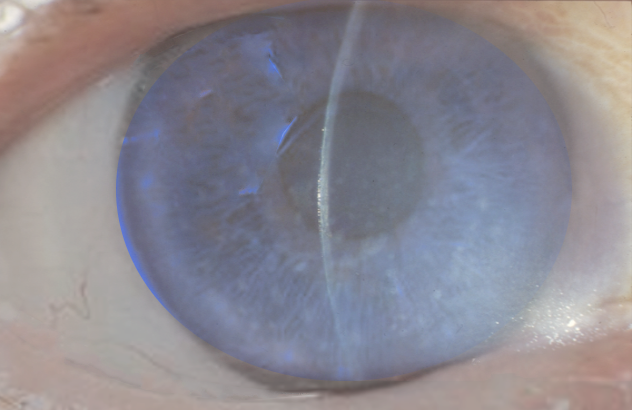

The tool commonly used for diagnosis and monitoring the progression of FED is a slit-lamp examination.

In early stages, guttata appear centrally and over time they spread to peripheral areas of the cornea but more horizontally than vertically. The guttata look like little droplets and distinguish them from normal age-related changes in the peripheral cornea is essential. As the disease progresses, the cornea’s Descemet’s membrane thickens and guttata become confluent (or merge).

As the disease advances, an examination might show that the stroma, a thicker layer of the cornea, has become swollen or has folds. In stage 2, tiny cysts will appear on the corneal surface. Stage 3 may see epithelial defects due to fluid collection beneath the epithelium, and in stage 4, subepithelial scarring occurs, and tissue overgrowth forms. Over time, the peripheral cornea may become vascularized, and stromal and epithelial edema reduce.

The measurement of central corneal thickness (CCT) in FED is useful in monitoring disease progression. Generally, a CCT greater than 640 micrometers signifies corneal edema. However, in patients with naturally thinner corneas, advanced FED may be present even when the CCT is lower than 600 micrometers.

Testing for Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy

The process for evaluating a patient suspected to have Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (FED), a type of corneal disease, involves several steps. Firstly, the doctor will need to understand the patient’s medical history thoroughly. Usually, symptoms of FED become noticeable in middle to old age, with patients complaining about blurry vision, glare, and a cloudy look on the surface of their eyes.

Your doctor might use a slit-lamp, a special microscope for examining eyes, to observe signs of FED such as guttata (small bumps on the back surface of the cornea) and swelling in the cornea. When the disease progresses, it can cause additional changes to the cornea, like blister-like formations, scarring, and formation of small blood vessels.

To get a close-up look at the cells of the cornea, your doctor might use a special type of microscope, called specular or confocal microscopy. This will help in detecting the loss of endothelial cells, the inner layer of cells of your cornea, which happens in FED. By measuring the thickness of your cornea (CCT), your doctor can determine the extent of swelling in your cornea. As FED progresses, your cornea becomes thicker due to this swelling. Both the cell count from the microscopy and the corneal thickness can be monitored over time to see how the disease is progressing.

Recent advancements have introduced the usage of Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) to visualize guttata in FED. But, this method cannot provide a numerical count of guttata and the image will only show a small region of the central part of the cornea.

To keep track of FED, routine eye exams every six months are essential. Early-stage FED can be managed with medical treatments, but it is crucial to note that vision can vary depending on the time of the day, being worse in the morning. For patients at an advanced stage of FED where it hampers daily life, surgical options might be considered.

Older patients with FED often have other health issues, like cataracts, age-related macular degeneration, and cardiovascular disease, which could add complexities to the surgical management of FED. The decision to have a cataract surgery alone or a combined procedure (DSEK/phacoemulsification), which includes a type of corneal transplant and a cataract surgery, depends on the patient’s corneal thickness and density of the corneal endothelial cells.

Treatment Options for Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy

There are various approaches to treating FED, which is a condition that causes blurry vision and pain in the eyes. Option includes medical treatments and surgeries, over-the-counter hyperosmotic saline drops or ointment, which help to dehydrate the cornea, the clear front surface of the eye. Some people find it helpful to use a hairdryer to gently blow warm, dry air onto the cornea, particularly for blurry vision in the mornings. Other treatment options like phototherapeutic keratectomy, amniotic membrane transplants, anterior stromal puncture, and conjunctival flaps may help to relieve painful symptoms, especially in the later stages of the disease when there is a rupture in the layers of the cornea.

FED is the main reason for people undergoing corneal transplants in the U.S. In fact, in 2016, it accounted for 36% of nearly 47,000 corneal transplants. Several surgical procedures can help with FED. Penetrating keratoplasty (PK), a surgery done to restore the cells of the cornea, was used to treat FED since the 1950s. But there are potential complications like high astigmatism (a defect in the eye or in a lens caused by a deviation from the spherical curvature), lengthier visual recovery time, suture related issues, persistent defects in the outer layers of the cornea, and repeat refractive surgery.

Due to these potential drawbacks of PK, other techniques have gained popularity, like Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK/DSEK), Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), posterior lamellar keratoplasty (PLK), and deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK). DSAEK, at present, is most commonly used for treating dysfunction of the cells in the innermost layer of the cornea. It leads to better visual outcomes than PK and causes fewer changes in vision and eye shape. DMEK transplants only the endothelial layer and Descemet’s membrane of the cornea and allows for the quickest visual recovery among all keratoplasty techniques. PLK and DLEK are used less frequently and are associated with a thicker graft-host stromal interface, meaning a thicker connection point between the transplanted cornea and the host tissue.

There have been recent exploratory treatments for managing the dysfunction of corneal endothelial cells that include the use of Rho kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632, which helps endothelial cells, the cells of the innermost layer of the cornea, to stick together and multiply. Corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL), which strengthens the cornea and decreases swelling, may improve vision and reduce discomfort in the eye. However, it has had mixed results so far. Research has also suggested the potential use of medications like lithium, N-acetylcysteine, and sulforaphane for treating FED. Additionally, innovative techniques such as adenovirus vector therapy and CRISPR gene editing could be helpful in managing FED, but their effectiveness is still limited currently.

What else can Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy be?

If someone is suspected to have Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (FED), doctors need to check for other conditions that could have similar symptoms. Such conditions might include:

- Guttata, a condition relating to changes in the cornea

- Aphakic bullous keratopathy or pseudophakic bullous keratopathy, particularly if there’s been a history of cataract surgery

- Recurrent corneal erosions, where the cornea’s outer layer repeatedly comes off

- Various forms of other corneal disorders such as Chandler’s syndrome, posterior polymorphous dystrophy (PPMD), congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED), and congenital hereditary stromal dystrophy

- Toxic anterior segment syndrome, a complication after certain eye surgeries

- Iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome, a rare eye disorder

- Hassall-Henle bodies, small bumps that form on the back layer of the cornea

- Herpetic disciform keratitis, a type of inflammation of the cornea

- Pigment dispersion syndrome, a condition where pigment cells of the iris shed and block the eye’s drainage channels

- Anterior uveitis, inflammation of the middle layer of the eye

- Interstitial keratitis, a condition causing cornea inflammation

- Herpetic stromal keratitis, a herpes virus infection affecting the cornea

Doctors would need to check for these conditions to make sure they don’t mistake one for another.

What to expect with Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy

FED is a condition that gradually worsens over time, and many individuals with it report a noticeable decline in their vision around their 60s to 70s. This often necessitates surgical treatment. Indeed, FED is the most common reason for corneal transplants in the United States.

However, there is good news. The majority of those who get a corneal transplant (known medically as keratoplasty) due to FED experience a significant improvement in their vision. A comprehensive review by Nanavaty and colleagues in 2014 found that there wasn’t a discernable difference in final vision quality between FED patients who had undergone different types of endothelial keratoplasty (like DSEK, DSAEK, DMEK, and femtosecond laser-assisted endothelial keratoplasty) and those who had a different type of transplant called PK.

Interestingly, patients who had the endothelial keratoplasty were seen to experience quicker and more reliable improvements in vision compared to those who had PK. This is thought to be because these surgeries help keep the structure of the eye intact. Those who undergo PK can face several complications.

Since 2013, one type of endothelial keratoplasty known as DMEK has overtaken PK as the most preferred treatment for disorders affecting the endothelium (the back layer of the cornea), and these endothelial keratoplasty techniques (including DSAEK and DMEK) are now regarded as the go-to treatment for FED. The results for patients are generally positive, with good vision outcomes reported.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy

There are several difficulties that can occur as a result of FED, including scarring on the surface of the eye and reduced ability to see well. Additionally, there are a number of potential problems that can happen after surgery. These include: the graft coming loose, being rejected, or failing; leakage of a clear fluid called aqueous; infection after the operation; increased eye pressure due to steroid use; formation of a cataract; issues with the wound healing; and complications involving the vitreous and retina in the eye. PK is a procedure that carries significant risks and complications. This can result in the shape of the eye changing after the operation and the wound tearing.

Surgery Implications:

- Graft coming loose, being rejected or failing

- Aqueous leakage

- Infection after the operation

- Increase in eye pressure due to steroid use

- Cataract formation

- Problems with the wound healing

- Complications involving the retina in the eye

- Change in eye shape after the operation

- Tearing of the wound

It’s been reported that detachment of the graft can occur in 0.9% to 36.4% of cases after DSAEK surgery. A significant study found a graft detachment rate of 36.4% after DMEK surgery. However, these graft detachments are usually able to be treated with an additional procedure that entails reattaching the graft with air or a heavy gas called sulfur hexafluoride. One particular study showed that DMEK patients had better vision over a distance and a 60% lower rate of graft rejection compared to DSAEK patients. But, DMEK had more instances of needing to reintroduce air to the eye because of graft detachment. The development of a cataract may also progress after keratoplasties surgeries.

Preventing Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy

Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (FED) is a disease that affects the eyes and is not preventable. The cause is often unknown. After diagnosis, it’s important for patients to regularly see their doctor for check-ups. These appointments allow the doctor to keep track of the disease progression through routine eye exams.

Doctors will collaborate with their patients to decide the right moment for medical treatment and potential surgery, depending on the disease’s progression. If the disease is at an early stage and is causing the cornea (the eye’s front layer) to deteriorate, medication alone may be enough. A type of eye drop called hypertonic saline can be used in the mornings to help dry out the cornea.

Some patients find it helpful to gently blow warm air over their eyes using a hairdryer in the mornings. This can help reduce any blurry vision caused by the disease. However, it’s crucial for patients to understand that FED is a progressive disease, which means it worsens over time. Therefore, FED will eventually demand surgery as the disease progresses.