What is Acute Mesenteric Ischemia?

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is a condition that occurs when blood flow to the intestines reduces suddenly. This can lead to a state where the tissues of the small and large intestines start to die off, possibly leading to severe infection, or sepsis, and in worst cases, death. Recognizing and treating AMI early is critical because its signs are often tricky to diagnose, and the condition can worsen rapidly.

The tricky part is that the symptoms of AMI are not distinct, meaning doctors must be very watchful to detect it. If AMI is not detected and treated early, between 60% and 80% of patients may sadly die as a result of it. AMI comes in two types, either as ‘occlusive,’ with blood flow blocked, or ‘nonocclusive,’ where some flow remains.

Occlusive variants can be further split into two: acute thromboembolism, a sudden blockage caused by a blood clot and acute thrombosis, a more gradual clot development. There is another form called mesenteric venous thrombosis, which is a type of AMI discussed more in other contexts.

What Causes Acute Mesenteric Ischemia?

Patients with embolism, or blood clots that obstruct blood vessels, often have a past medical history of heart conditions, including recent heart attacks, heart failure, and irregular heartbeats known as atrial fibrillation. These embolisms can be caused by chunks of a blood clot traveling through the bloodstream, heart-related blood clots, or a chunk of a fatty deposit called an atheromatous plaque that broke off after surgery.

Individuals with a type of blood clot called a thrombus often experience abdominal pain after eating, which may lead them to avoid food and lose weight. This type of clot can be caused by the buildup of fats, cholesterol, and other substances called plaques in and on the artery walls, a disease known as atherosclerosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm or dissection, or conditions that reduce the amount of blood the heart pumps, due to secondary reasons such as dehydration, heart attacks, or heart failure.

Patients with non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI), a problem with blood supply to the intestines that’s not caused by a blockage, are usually critically ill, have multiple significant health problems, and are not stable in terms of the dynamics of their blood flow. Causes can range from drugs that reduce blood flow, such as vasopressors and ergotamines, to low blood pressure due to serious medical conditions, like heart attacks, infections of the bloodstream (sepsis), heart failure, and kidney disease, and patients who have recently undergone major surgeries, such as heart and abdominal surgeries.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

AMI, or acute mesenteric ischemia, is an uncommon condition, observed in just one out of every 1000 hospital admissions. It predominantly affects women, older patients, and those battling multiple serious health issues.

- 40% to 50% of all AMI cases are due to arterial embolism.

- Arterial thrombosis is responsible for 25% to 30% of AMI cases.

- Lastly, NOMI, or non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia, accounts for 20% of all AMI instances.

Signs and Symptoms of Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

Patients with Acute Mesenteric Ischemia (AMI) commonly experience abdominal pain, but this isn’t always reflected in physical examinations. This discomfort tends to become noticable only when the whole bowel wall becomes affected, often when tissue death (necrosis) begins. In the case of an embolic disease, usually the bowel suddenly empties, leading to intense pain. This condition rapidly progresses to a state of reduced blood supply (ischemia) and necrosis, due to the limited backup blood flow. Thrombosis, the formation of a blood clot within a blood vessel, might take days or weeks to advance, with abdominal pain gradually getting worse.

Additionally, patients might exhibit symptoms like diarrhea, bloating, bloody stool, and crucially, a history of pain after eating – hinting at ongoing mesenteric ischemia. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) progresses slowly, and the associated abdominal pain is not localized, varying in intensity and consistency. Patients with NOMI are usually critically ill, might have septic shock, heart disease, and respiratory failure. They are likely to have low blood pressure and hence, are often given vasopressor agents to increase the pressure.

Testing for Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

Lab tests and biological markers for Acute Mesenteric Ischemia (AMI), a severe condition affecting the intestines, aren’t very specific and can’t diagnose the condition alone. The levels of D(-)-lactate and lactate dehydrogenase (enzymes found in the body) may be higher in AMI’s later stages.

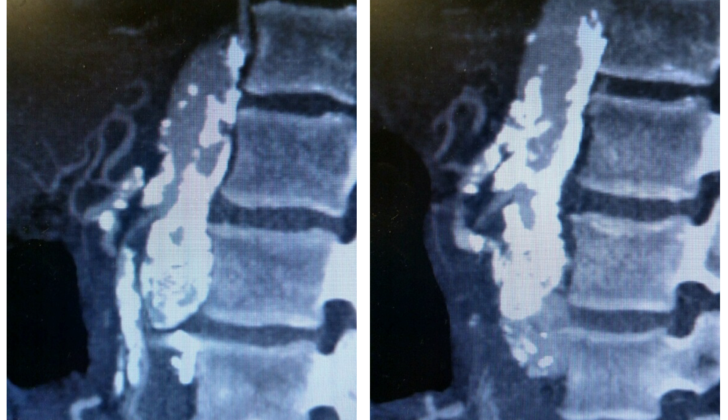

CT angiography, a scan that allows us to see the body’s blood vessels, is the preferred way to picture all kinds of AMI. This technique is pretty accurate, with a success rate ranging from 96% to 100% for detecting AMI and 89% to 94% for being sure it’s there when other conditions aren’t confusing the diagnosis.

Narrow tube-like devices (catheters) used to create angiograms (images of blood vessels) are not typically used in the early diagnosis stages of AMI. Although these devices can be used in conjunction with endovascular treatments (procedures involving the blood vessels), they are usually avoided initially because the extra stress of the operation can be hard on patients who are already seriously sick.

Easier X-rays of the stomach, duplex ultrasonography (a two-part ultrasound technique), and magnetic resonance angiography (another imaging technique) have limited use in diagnosing AMI and aren’t commonly used.

Treatment Options for Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

The first step in medical treatment is to regulate the body’s fluid levels and correct any imbalance in electrolytes. Doctors avoid using medications that may cause the blood vessels to spasm, such as vasopressors and alpha-adrenergic agents. Before surgery, patients should receive antibiotics that cover a wide range of bacteria to prevent a potentially serious infection, called abdominal sepsis, from developing if dead bowel tissue needs to be removed.

An early surgical operation is required to determine the extent of restricted blood flow and the spread of tissue death. The primary goal of surgery is to restore blood supply to the bowel, and removal of dead bowel tissue is necessary. After enhancement of blood supply, doctors check the bowel for signs of health, like checking for pulses using a device called a continuous wave Doppler, observing the movement of the bowels, and looking for normal color. Depending on where and how the blood vessel is blocked, either open or less invasive surgical interventions can be used to treat blockage in the mesenteric artery, which is the main artery supplying the bowel. In the follow-up surgeries, bowel removal happens in 53% of cases and 31% in the first surgery that aims to restore blood supply. Because it’s difficult to determine the extent of bowel tissue death, another surgery is usually needed 12 to 48 hours after blood supply is restored.

When the problem is not a blockage, but spasms in the blood vessels, a condition known as NOMI, the treatment is medically focused and aims at dealing with the underlying cause of the reduced blood flow. An intravascular procedure using drugs like papaverine can be an option to relax the spasms.

What else can Acute Mesenteric Ischemia be?

Spotting the signs of Acute Mesenteric Ischemia (AMI) quickly is crucial to prevent severe health problems and increase the chances of survival. Diagnosing AMI can be tricky as the symptoms are quite general, which means doctors need to be extra cautious when examining patients with potential symptoms of this serious condition.

Patients with AMI might have severe stomach pain that seems more intense than would be expected from a physical exam. Also, if a patient has risk factors that make them more likely to have a heart condition or blood clots in their legs or arms, doctors should also consider the possibility of AMI.

There are other conditions that can cause severe stomach pain and can be mistaken for AMI. These include inflammation of the colon (acute colitis), a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (a serious condition where a large blood vessel at the center of your body rips open), a bowel obstruction, diabetic ketoacidosis (a serious complication of diabetes), a tear in the wall of the stomach or intestines, and cancer.

What to expect with Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

The outlook for people with Acute Mesenteric Ischemia (AMI), a type of serious stomach problem, is not good. Patients often suffer greatly from the disease and many don’t survive. Although the survival rate has been improving since the 1960s, still between 60% to 80% of people unfortunately die with this condition. The specific type of AMI a patient has can influence their survival. For example, patients with acute embolism (a type of blood clot) generally live longer than those with other forms of AMI such as nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) or acute thrombosis (a different, sudden blood clot problem).

Some factors increase the risk of death, including being older, needing a part of the bowel removed during a follow-up operation, having too much acid in the blood (metabolic acidosis), having poorly functioning kidneys (renal insufficiency), and how long the symptoms have been present.

According to a study by Gupta and others, more than half of patients (56%) suffered from further complications within 30 days of their operation. Common complications can include needing to use a ventilator (a breathing machine) for more than 48 hours, getting a serious infection that affects the whole body (septic shock), getting pneumonia (an infection in the lungs), and sepsis (another type of severe infection).

Many patients needed further surgical interventions, with 30% needing to be readmitted to the surgical department within a month. In addition, 14% of patients had to stay in the hospital for more than 30 days.