What is Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula)?

Bouveret syndrome is a rare problem that can happen with gallstone disease, affecting only 0.3% to 0.5% of patients. It blocks the exit of the stomach, known as gastric outlet obstruction. This unusual gallstone complication happens when a large gallstone gets stuck at the beginning of the small intestine (proximal duodenum) or at the opening of the stomach (pylorus). This can happen when a spontaneous, abnormal connection (fistula) forms between the gallbladder and the small intestine or the stomach. This syndrome is so rare that only 315 cases have been recorded over 50 years between 1967 and 2016. It was first identified by French surgeon M. Beassier in 1770. Later in 1896, a French doctor named L. Bouveret gave a detailed report on this condition, so it was named after him.

Bouveret syndrome has a high death rate, estimated to be between 12% to 30%. This is because it’s usually found in elderly individuals, its diagnosis can be delayed due to vague symptoms and the complexity of the disease. Also, because this condition is so rare, doctors have not agreed on the best way to diagnose and treat it. Options for treatment could include endoscopy (a procedure that uses a long, thin tube to look inside the body), laparoscopic surgery (“keyhole” surgery), and open surgery.

What Causes Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula)?

Bouveret syndrome is a rare type of gallstone ileus, a condition where a gallstone blocks the intestine. This happens when a gallstone moves through a hole, known as a fistula, and blocks the passage from the stomach to the intestines, and sometimes other parts of the intestines as well. Usually, the hole forms between the gallbladder and a part of the stomach or intestine.

Certain factors increase the risk of developing Bouveret syndrome. These include having a history of gallstones, particularly stones larger than 2 to 8 cm, being female, and being over 60 years old. It’s also been noted that 43% to 68% of patients with Bouveret syndrome have a history of recurring gallbladder pain, yellowing of the skin (jaundice), or inflammation of the gallbladder (acute cholecystitis).

Risk Factors and Frequency for Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula)

Bouveret syndrome is a very rare condition and is responsible for 1 to 3% of all blockages caused by gallstones in the digestive tract. It constitutes 0.3 to 5% of all gallstone complications. Most of these gallstones are quite small and either go unnoticed or cause a blockage in the area of the small intestine known as the terminal ileum.

It mostly affects elderly, frail women, with the average age of patients being 74 and a female-to-male ratio of 1.9. Due to this, Bouveret syndrome has high rates of sickness and death.

Signs and Symptoms of Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula)

Bouveret syndrome is a medical condition that doesn’t always show specific symptoms. Often, people with Bouveret syndrome may have on-and-off episodes of nausea and vomiting, a bloated abdomen, and pain. This pain might change due to the gallstone moving to different locations. Other signs can include pain in the upper middle or right upper part of the abdomen, dehydration, and weight loss. Some may also vomit blood due to damage to the duodenum and celiac artery or some may vomit gallstones. Typically, these symptoms can be present for about 5 to 7 days before a person seeks medical help. It should be noted, though, that the severity of the pain doesn’t always match the amount of physical damage in the body.

A doctor’s examination may not always clearly indicate Bouveret syndrome. But, a doctor might notice signs like dry mucous membranes, a bloated abdomen, abdominal tenderness, unusual bowel sounds, and jaundice, which is a yellowing of the skin and eyes caused by a blockage.

- Nausea and vomiting

- Bloated Abdomen

- Abdominal Pain

- Pain in the upper middle or right upper part of the abdomen

- Dehydration

- Weight loss

- Blood in vomit (rarely)

- Vomiting gallstones (rarely)

- Symptoms usually start 5 to 7 days before seeking help

Potential signs a doctor might notice include:

- Dry Mucous Membranes

- Bloated Abdomen

- Abdominal Tenderness

- Unusual Bowel sounds

- Jaundice

Testing for Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula)

If you have Bouveret syndrome, laboratory tests might not conclusively show it. In some cases, these tests might reveal liver problems or increased bilirubin levels, which can cause jaundice (yellowing of the skin), but this only happens in about a third of patients. You might also have an elevated white blood cell count, electrolyte abnormalities, acid-base imbalances, or even kidney failure, but these factors can be impacted by other health conditions, how severe the inflammation is, and how well your body can compensate.

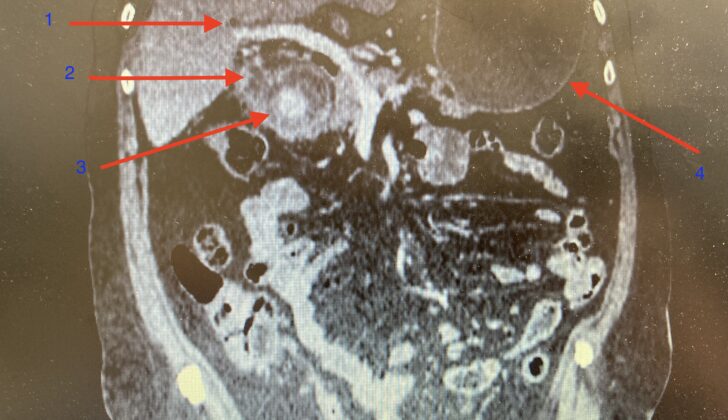

Imaging can provide additional clues to diagnose Bouveret syndrome. Doctors look for a combination of air in the bile ducts, bowel obstruction, and a misplaced gallstone, a set of symptoms known as Rigler’s triad. However, this combination is only present in 40% to 50% of cases. An ultrasound may be helpful in showing inflammation of the gallbladder, distended stomach, air in the bile ducts, and misplaced gallstones. But, it can be challenging to see these signs clearly due to intervening gas in the intestines. Furthermore, if the gallbladder is shrunken, it might be hard to identify the exact location of the gallstone using ultrasound.

Abdominal X-rays might be useful, but they are not specific. They might reveal air in the bile ducts, bowel obstruction, a misplaced gallstone, and distention of the stomach. But only about 21% of Bouveret syndrome cases can be diagnosed with abdominal X-rays alone. CT scans are more reliable, with a 93% chance of detecting Bouveret syndrome accurately. They are also able to provide valuable information about the presence of a hole between organs (fistula), presence of a pocket of infection (abscess), the state of inflammation around organs, and information about the size and number of gallstones.

In some situations, when patients can’t take oral contrast or are constantly vomiting, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can be utilized. This imaging technique can differentiate stones from fluid, visualize the fistula accurately, and doesn’t require the use of oral contrast material. Doctors can also perform an Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), a procedure that allows viewing the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract. This has the added advantage of being able to potentially remove the stone at the same time, although this is often unsuccessful and can lead to further complications. Approximately 20% to 40% of Bouveret syndrome cases are finally diagnosed during surgery for a bowel obstruction of unknown cause. This applies particularly to 15% to 25% of gallstones that blend in with the surrounding tissue and aren’t visible on CT scans.

Treatment Options for Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula)

Bouveret syndrome, a rare condition where a gallstone blocks the opening to the small intestine, typically doesn’t improve on its own. Because stone can cause more blockages further down, the main treatment is usually an endoscopic intervention, which involves inserting a long, thin tube with a tiny camera (an endoscope) into the body to visualize and remove the stone. While fewer people tend to experience complications or die after this type of procedure compared to surgery, it is less likely to work.

Before an endoscope is inserted, it’s important to insert a nasogastric tube to reduce air in the stomach and, therefore, the risk of inhaling stomach content into the lungs. Over the past 20 years, new endoscopy techniques have been developed, improving success rates from 13.6% – 18% to 43%. These less invasive treatments, such as endoscopic retrieval, extracting gallstones using tools such as graspers, nets, snares or baskets, and breaking stones into smaller pieces using various types of lithotripsy, have become more common. Protective measures can be taken to avoid injury to the esophagus during stone extraction.

Mechanical lithotripsy is a common method for breaking stones into smaller pieces, and the procedure is often performed under x-ray to avoid accidentally entering the small pouch that stores bile, known as the gallbladder. Other types of lithotripsy include electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL), which uses high-intensity shock waves, laser lithotripsy, and extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL). However, these techniques can potentially cause bleeding and tearing.

Despite these advancements, less than two-thirds of gallstones are successfully visualized and removed using an endoscope. In some cases, multiple procedures may be needed, or surgery may be considered if endoscopy fails or is not available. In the past, surgery was considered the first line of treatment because it’s more successful than endoscopy-based treatments but it does have a higher risk, especially for older patients with other health problems.

During surgery, methods such as open gastrotomy, pylorotomy, or duodenotomy can be used to remove the stone. For hard-to-reach stones, endoscopy can also be used during surgery to help position the stone before extraction.

Laparoscopic surgery, which involves small incisions and the use of a camera to guide the surgeon, can be less risky than open surgery and might be the preferred approach when endoscopic therapies are not available or unsuccessful. However, conversion to open surgery may be necessary in complex cases.

The decision to remove the gallbladder and repair the small pouch that stores bile can be debated, especially considering the patient’s overall health. Although the repair of the small pouch that stores bile can prevent the recurrence of gallstone-related complications, it can come with higher risks which won’t be appreciated in patients with poor surgical candidacy. A decision to remove the gallbladder may be made based on factors like the patient’s age, risk of gallbladder cancer, or the presence of other gallbladder conditions.

What else can Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula) be?

There are various reasons why an individual might experience a medical issue. These can often be grouped into categories, such as:

- Congenital causes (conditions you’re born with): An example is a ‘Duodenal web,’ which is a thin membrane in the first part of the small intestine.

- Inflammatory Causes (conditions causing tissue inflammation): These can include conditions like erosive gastritis (stomach lining inflammation), peptic ulcer disease (sores on the lining of your stomach or the upper part of your small intestine), and Crohn’s disease (an inflammatory bowel disease that affects the lining of your digestive tract).

- Malignant Causes (cancer): This group might include gastric antral carcinoma (a type of stomach cancer), duodenal carcinoma (cancer in the beginning section of the small intestine), pancreatic carcinoma (pancreatic cancer), ampullary carcinoma (cancer in the part of the bile duct that passes through the pancreas), and cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer).

What to expect with Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula)

Bouveret syndrome usually has a favorable outcome if it’s diagnosed and treated promptly.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula)

If Bouveret syndrome is not treated, it can lead to ongoing issues like loss of appetite, dehydration, nutrient deficiencies, and imbalance in body salts. The biggest concern is intestinal perforation, which can cause serious health problems.

The complications you experience can also depend on the type of treatment. For example, if the procedure to break down the gallstone is not completely successful, the gallstone may cause a bowel obstruction again. The shock waves used in this procedure can also unintentionally damage nearby organs. If the abnormal connection, or fistula, is not removed, there’s a chance that Bouveret syndrome could happen again. This could also lead to an infection in the bile ducts, inflammation of the pancreas due to a gallstone, and potentially even an increased cancer risk.

Any surgical procedure carries with it risks of bleeding and infection. Specifically, the surgical removal of the gallbladder could accidentally injure the bile ducts, especially if the area is inflamed.

- Ongoing problems with eating, dehydration, nutrient deficiencies, and electrolyte imbalance

- Intestinal perforation causing serious health issues

- Recurrent bowel obstruction if gallstone isn’t completely broken down

- Damage to nearby organs from shock wave treatment

- Recurrent Bouveret syndrome, bile duct infection, gallstone pancreatitis and potential increased cancer risk if fistula isn’t removed

- General surgical risks of bleeding and infection

- Potential injury to bile ducts during gallbladder removal, especially if area is inflamed

Preventing Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula)

Patients who have had an endoscopic procedure or surgery to remove stones causing blockage, but the tunnel-like opening called cholecystoduodenal fistula was not closed during the process, should be aware of the potential risks. These risks include the possibility of recurrence of bowel obstruction due to migration of other stones, biliary sepsis – a severe infection in the bile, and acute pancreatitis – a sudden inflammation of the pancreas. As a result, it’s important these patients head to the emergency department immediately if they experience severe stomach pain and vomiting.