What is Duodenal Trauma?

Duodenal trauma, or injury to the duodenum, is a rare but extremely dangerous condition. Identifying and managing these injuries can be challenging and often, these injuries aren’t discovered until a late stage. This can result in a higher risk of serious health complications or even death. The difficulty in treating duodenal trauma is due in part to its complex structure and function.

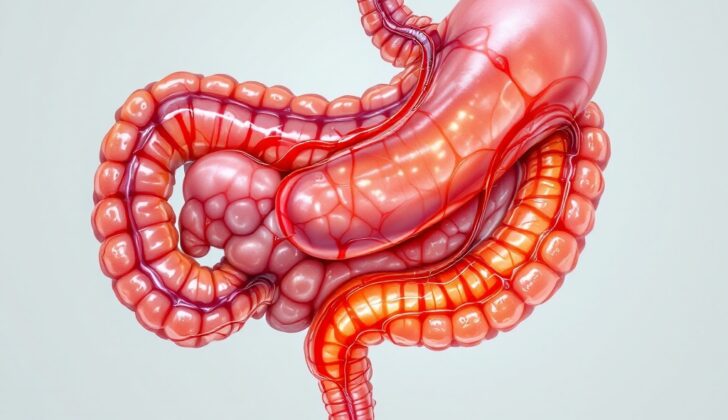

The duodenum is the first and smallest part of the small intestine, measuring only 20 to 30 centimeters long. The name comes from the Latin word ‘duodeni’, which means ‘twelve each’. This is a nod to its length, which is about the same as the width of twelve fingers. The duodenum starts after the stomach and ends at the Ligament of Treitz, where it turns into the next part of the small intestine called the jejunum. It’s wrapped in a ‘C’ shape around the pancreas head. This particular shape is often referred to as the “surgical soul” because of the critical outcomes that can occur if it’s damaged.

The duodenum itself is divided into four different parts. The first part, known as D1, is at the top and is where the stomach empties its contents. The second part, D2, is where digestive juices from bile and pancreas enter the small intestine. Then comes the third part, D3, which is the horizontal part of the duodenum. Finally, part D4 rises upward to meet the jejunum. The ligament of Treitz is a muscle in this area, holding everything in its right place.

Duodenum falls into the unique category of being both within the abdominal cavity (peritoneal) and behind it (retroperitoneal). Part D1 is inside the abdominal cavity, while the latter parts, D2 and D3, are behind it. D4 goes back into the abdominal cavity.

Functionally, the duodenum mixes pancreatic and bile fluids with the gastric juices released from the stomach. Along with around 2,500 to 3,500 mL of saliva and gastric fluids, the duodenum also receives an average of 500 to 1,000 mL of bile and 1,000 to 1,500 mL of pancreatic secretions each day. This totals to about 5 liters of fluid flowing through the duodenum each day, not counting any extra fluids consumed orally. This high flow rate makes managing duodenal injuries particularly hard and increases the risk of fluid leakage and fistula development if the mucous lining of the duodenum is damaged.

What Causes Duodenal Trauma?

Injuries typically fall into two categories: blunt or penetrating. Mostly, injuries to the duodenum, a section of the small intestine, come from penetrating sources. In fact, nearly 78% of these injuries are due to penetrating causes, while only around 22% are from blunt sources.

Penetrating injuries mainly occur from gunshot wounds (81%) and stabbings (19%). As for blunt injuries, most of them happen due to car accidents, which account for 85% of the cases. Fights and falls are also other causes of blunt injuries.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Duodenal Trauma

In the US, trauma is the fourth-leading cause of death, especially poignant in the age range of 1 to 44, where it poses the highest risk. Trauma cases noticeably tower above trauma-related death rates, with 30 times the amounts needing hospital admission and up to 300 times reporting to Emergency Departments. Young adult males frequently experience trauma, though the rates are growing within older populations, with these groups bearing a higher risk of sickness or death.

Some general risk factors heightening the likelihood of sickness or death from trauma are low income, race other than Caucasian, existing health conditions, and residing in an area lacking level I or II trauma centers, also known as ‘trauma deserts’.

Among trauma cases, duodenum (a part of the small intestine) trauma is rare, presenting in only 3.7 to 5% of all abdominal injuries. Like most trauma cases, this too is most common among young males, with a male-to-female ratio of 5:1. 70% of such injuries occur between the ages of 16 to 30.

- Trauma ranks fourth in causes of death in the US and first among ages 1 to 44.

- For each trauma-related death, 30 times more people need hospitalization, and up to 300 times more need treatment in an Emergency Department.

- Trauma is more common in young adult males but is increasing among the elderly, who may experience more severe health issues or death.

- The risk of severe health issues or death from trauma is higher in people with low income, non-Caucasians, those with existing health issues, and living in ‘trauma deserts’, areas lacking well-equipped trauma centers.

- Duodenal trauma is rare, affecting 3.7 to 5% of abdominal injuries.

- Most duodenal trauma patients are young males, with a male-to-female ratio of 5:1.

- 70% of such injuries occur in people between 16 and 30 years old.

Signs and Symptoms of Duodenal Trauma

When dealing with a potential duodenal injury (an injury to the first part of the small intestine), the patient’s history and physical check-up can often seem quite usual. The process of evaluating the trauma starts with a basic check for key body functions. This includes checking if the airway is open, if they are breathing normally, if the blood circulation is normal, if there are any disabilities, and if the patient was exposed to anything harmful.

After this, a more detailed check-up is performed which looks at the entire body for any injuries. At the same time, the doctor will also get a broader sense of the patient’s medical background and recent health activity. This involves knowing about any allergies, medications they’re currently on, past medical issues, the last time they ate anything, and what took place leading up to their arrival at the hospital.

The physical examination specifically concerning the possible duodenal injury will focus mainly on the stomach area. The check-up kicks off with a visual examination for any swelling, bruising, cuts, penetrating wounds, and possible protrusion of organs through wounds. In cases where there’s been a penetrating wound, the number of wounds and their locations are noted down. Although typically a physical examination would then involve listening to sounds within the body, this step is of limited use when dealing with severe abdominal injuries and is often skipped.

Next, the doctor will do a tap test and a touch test on the stomach area to check for any abnormalities and signs related to the lining of the abdomen. Such signs can be severe tenderness, pain when pressure is released quickly, protective muscle contractions, and rigidity.

The background information on a patient largely involves the circumstances around the injury, such as how it happened. Symptoms which could signal a duodenal injury could include stomach pain, pain spreading to the back, chest pain, feeling nauseous, throwing up, or vomiting blood. There have been rare instances where an injury to the duodenum has caused severe pain in the testicles and prolonged erection, which is due to nerve activation along the vessels to the testicles.

Testing for Duodenal Trauma

For any injury, the first step of the evaluation should focus on the essentials: checking the airway, breathing, and circulation. Spotting a duodenal injury (an injury to a part of the small intestine) can be challenging due to its tucked-away location in the body, so doctors need to be especially alert. Physical examination might not be enough to detect such injuries.

If a patient has symptoms like severe abdominal pain or even an exposed organ following an abdominal injury, they should immediately be taken for a surgical procedure called exploratory laparotomy. This is also the case for patients who are unstable after a penetrating abdominal trauma – but only once it’s confirmed that the abdomen is the cause of instability.

Advanced techniques are used to pinpoint the cause and extent of the injury. One such method is the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST), which uses ultrasound technology to detect any fluid build-up in the abdomen. While Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL), a procedure to check for blood in the abdomen, can be considered, it has been largely replaced by the more efficient FAST technique.

If the patient is stable, a CT scan, which provides detailed images of the body, can be used for evaluation. In some cases, particularly stable patients with penetrating abdominal trauma may undergo diagnostic laparoscopy, a minimally invasive surgical procedure, depending on the circumstances.

Lastly, the severity of a duodenal injury is graded using a scale developed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST).

Treatment Options for Duodenal Trauma

The duodenum, which is located deep in the body, can be hard to reach and properly visualise for surgeons. To get a clearer view, surgical techniques such as the Kocher maneuver and Cattel-Braasch maneuver are used.

The Kocher maneuver involves making a cut along the back side of the duodenum and then gently pushing it and the head of the pancreas towards the middle of the body. This allows surgeons to see most of the duodenum, including its first and second parts.

However, the smaller parts of the duodenum i.e., D3 and D4, are tougher to reach and require a Cattel-Braasch maneuver. This moves the ascending colon by extending the incision along the right edge of the abdominal cavity. Then the incision is extended and cut around the cecum and the rear attachments of the mesentery towards the ligament of Treitz. This gives surgeons a panoramic view of the hidden parts of the retroperitoneum, including the D3 and D4.

The management of injuries to the duodenum depends on the extent of the injury and how it impacts nearby structures. Most simple duodenal hematomas, which can be seen on a CT scan, can be treated without surgery and typically involve resting the digestive system and constant monitoring through abdominal exams. Sometimes, these hematomas can worsen and block the duodenum. If this happens, a nasogastric tube can be used to relieve the blockage until the swelling goes away.

A contrast study of the upper gastrointestinal tract can be done every 5 to 7 days to check on the progress. If the blockage doesn’t clear up after 2 or 3 weeks, surgical removal may be needed.

When a duodenal hematoma is found during an operation, the Kocher maneuver should be performed and the duodenum should be thoroughly inspected for any signs of rips or tears. If none are found, these hematomas are usually treated with non-surgical methods.

Tears or rips in the duodenum caused by trauma typically require surgery. The best treatment for most duodenal lacerations is through stitching it up directly. Tears involving the serosa and partial-thickness lacerations can be stitched up using the Lembert method. It’s estimated that this option is safe for about 70-85% of duodenal injuries.

Sometimes, when a serious injury occurs, or when the injury involves the ampulla, a surgical connection between the duodenum and the jejunum, known as a roux-en-Y duodenal-jejunostomy, should be considered. In cases of severe injuries involving the pancreas, the patient might require a pancreaticoduodenectomy, also known as the Whipple procedure. This should never be done in an emergency and should only be done after the patient has been stabilised.

Certain procedures, such as duodenal diverticularization and triple-ostomy repair, have largely lost their popularity. These involved several different routes for draining fluids and have been linked with unnecessary complications. A modified triple-tube repair is another alternative method that has been used in the past.

What else can Duodenal Trauma be?

When someone experiences an injury to their duodenum, which is the first part of the small intestine, the symptoms might not be very clear. Such symptoms could also indicate a variety of other injuries:

- Injury to the esophagus (the tube that connects your throat to your stomach)

- Stomach injury

- Injury to other parts of the small bowel (the jejunum or ileum)

- Injury to the colon and rectum

- Injury to the mesentery (the tissue that holds your intestines in place)

- Mesenteric hematoma (a blood clot in the mesentery)

- Trauma to blood vessels inside the abdomen

- Injury to the pancreas

- Liver injury

- Spleen injury

- Kidney injury

- Bladder injury

So it’s very important for doctors to consider all these possibilities when diagnosing a duodenal injury.

What to expect with Duodenal Trauma

Injuries to the small intestine, specifically the duodenum, are associated with increased risk of complications and death. Generally, complications are seen in 22 to 27% of cases. The fatality rate is reported to be between 5 and 30%, depending on the severity and timing of the injury.

The fatality rate also changes based on the severity of the injury: it’s 8.3% for a mild injury (grade I), 18.7% for a moderate injury (grade II), 27.6% for a severe injury (grade III), 30.8% for a very severe injury (grade IV), and 58.8% for a critical injury (grade V). Deaths soon after the injury are typically due to severe blood loss, while fatalities occurring later on can be due to complications such as infection, sepsis, and organ failure.

One of the major factors in predicting the chance of survival is the timing of the diagnosis. If the diagnosis is delayed by more than 24 hours, the risk of death nearly quadruples.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Duodenal Trauma

Common complications after a medical procedure can include:

- Injury that wasn’t identified during the procedure

- Formation of a pocket filled with pus inside the abdomen

- An abnormal connection formed between the duodenum (part of the small intestine) and the skin or another organ

- Blockage of the duodenum

- Recurrent inflammation of the pancreas

- Bleeding

Preventing Duodenal Trauma

Injury to the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine, can happen due to various causes. Most of these injuries are caused by things like gunshot wounds and stabbings, so one way to prevent them is by reducing violence in general. This could involve working together with local community groups to encourage safe handling and storage of weapons.

Moreover, educating the community on safe driving can also help prevent these types of injuries. This can include promoting the use of seatbelts, advising against distractions while driving, and advocating for generally careful and safe driving habits.