What is Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)?

Esophageal injury (EI) is a rare but serious problem that can occur during incidents of trauma. This type of injury, or perforation, refers to a condition where the esophagus, or the tube that connects your throat to your stomach, is damaged. This damage allows the inner contents to leak into the surrounding area within the chest, causing both local and body-wide inflammation, and eventually leading to a severe infection called sepsis, which can lead to serious illness and even death.

Esophageal injuries can come about in a bunch of different ways. Sometimes they are caused by medical procedures, like when a doctor uses an endoscope to look inside your body, during tube placements through the nose and into the stomach, or during surgical operations. They can also occur from trauma, like car accidents or injuries from gunshots or knives. There are other causes as well, like swallowing something that shouldn’t be swallowed, the esophagus bursting on its own (a condition known as Boerhaave syndrome), or swallowing harsh substances like acid.

It’s more common for esophageal injuries to be caused by medical procedures than by trauma. People who have a high risk of experiencing these types of injuries often have other health problems too.

What Causes Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)?

The esophagus is a muscular tube, about 25 cm long, that extends from the lower end of the voice box to the stomach. It begins in the neck at the level of the sixth neck vertebra and passes in front of the bony spine before settling behind the heart and lungs. It then ends in the upper portion of the stomach. The esophagus has four layers: the inner surface, beneath the surface layer, the muscle layer split into two parts, and the outermost layer.

It can be broken down into three main sections: the part in the neck, the part in the chest, and the part in the belly. The blood supply to each part comes from different arteries: the lower neck artery nourishes the neck portion, arteries from the heart and lungs nourish the chest portion, and two arteries related to the stomach provide the abdominal section. The veins responsible for moving blood away from these areas differ as well, with the inferior neck vein, chest and bronchial veins, and veins in the stomach carrying out this task respectively.

The top part of the esophagus can be controlled voluntarily, while the middle and bottom parts function automatically. Each of these three sections has different injury patterns and symptoms because they are located near different structures in the body. Therefore, how we diagnose and treat injuries can change depending on which section is involved. Esophageal injuries are rated using a scale that ranges from contusions or partial tears (Grade I) to disruption of more than 2cm of tissue or blood vessels (Grade V).

Injuries can happen anywhere along the esophagus. A common fix for injuries in the belly part is surgery, but most injuries in the neck and chest sections can be initially managed without surgery. However, the chosen treatment method usually depends on the patient’s symptoms and if there are other injuries nearby. The neck part of the esophagus is surrounded by the windpipe, the spine, and a sheath containing the carotid artery. Injuries in this area are mainly due to damage to these vital neighboring areas. The neck part is the most likely to get injured, but its injuries can be managed effectively which has led to a low chance of death. Injuries in the chest part happen less but are riskier and more fatal because of its proximity to critical body structures. Finally, the belly part gets injured the least, with an average level of risk and fatality. The potential for complications after an injury in this area is higher because it lacks a protective outer layer and gets less blood supply.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)

Traumatic injuries to the esophagus are quite rare, even in large trauma centers where only one to two cases might be seen each month. Among these, injuries from penetrating trauma like a gunshot or stab wounds are more common than those from blunt trauma, with a ratio of about 10-to-1. In the United States, the primary causes of these penetrating injuries include gunshot wounds (making up roughly 75% of cases) and stab wounds (about 15% of cases).

These types of injuries can also be accompanied by damage to nearby areas meaning it can impact the organs located around the esophagus like the trachea, heart, and lungs. In a smaller number of cases, an injury might involve perforations to both the esophagus and trachea which can be life-threatening. The possibility of fatal outcomes dramatically climbs if the injuries also impact any major blood vessels. Also, if the traumatic event is around the area of the esophageal hiatus (an opening in the diaphragm where the esophagus passes through to connect to the stomach), it could mean other key structures like the aorta, heart, liver, spleen, colon, pancreas, and stomach are also injured.

The level of disability and risk of death from an esophageal injury depends on a few different things including when the injury was identified, if there were any injuries to surrounding structures, if contamination occurred due to the injury, the severity of the injury, and the general health status of the patient. The best outcomes are seen with early detection and treatment of the injury, minimal damage to surrounding structures with little or no contamination, and when the patient doesn’t have other significant health conditions. However, diagnosing and treating traumatic esophageal injuries can be challenging, as there may also be damage to the surrounding tissues and risks of contamination. This makes it vital for a trauma surgeon to understand the different ways an esophageal injury can occur, maintain a high level of suspicion, and act quickly if an injury is suspected.

Signs and Symptoms of Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)

It’s important to carefully evaluate anyone who might have an esophageal injury. These examinations include a detailed medical history, a thorough physical examination, and the identification of any relevant risk factors in the patient’s health or circumstances. Accurate imaging also plays a crucial role in identifying this condition.

The main symptom of an esophageal injury is usually a severe pain in the chest. This pain may also spread to the back or left shoulder, depending on where the injury has occurred and the extent of the damage. About 25% of people with these injuries may also experience vomiting and/or difficulty breathing. This might become even more common if the diagnosis or treatment are delayed for any reason.

Another symptom that can occur is known as Mackler’s Triad. This syndrome includes subcutaneous emphysema (air trapped under your skin), chest pain, and vomiting. Still, it’s only identified in around one in seven cases of esophageal perforation. Another sign is something called the Hamman sign, which is a ‘crunching’ or ‘rasping’ sound that’s in sync with the person’s heartbeat. This can be detected in up to half of esophageal injury cases.

- Severe chest pain

- Radiating pain to the back or left shoulder

- Vomiting

- Difficulty breathing

- Subcutaneous emphysema, chest pain, and vomiting (Mackler’s Triad)

- ‘Crunching’ or ‘rasping’ sound (Hamman sign)

Careful examinations can give valuable information about the location and severity of an injury, which in turn helps in deciding the best diagnostic imaging to use. For example, an injury to the cervical (neck) part of the esophagus might come with symptoms like changes in voice, difficulty swallowing, and subcutaneous emphysema. Therefore, the imaging would be tailored towards these symptoms. On the other hand, if the injury is to the gastroesophageal junction (where the esophagus meets the stomach), the main symptom would likely be acute abdominal pain. So, the imaging would be focused more on finding the source of contamination in the abdominal cavity. Similarly, with an injury to the chest portion of the esophagus, the patient may have symptoms related to the chest cavity or the surrounding layers.

It’s especially important to be vigilant when dealing with trauma victims who might have an esophageal injury. They should be closely monitored for a high temperature (more than 38.5 C), a rapid heartbeat, or a crackling sound on physical examination. This is because the condition can quickly deteriorate into septic shock if it’s not detected early.

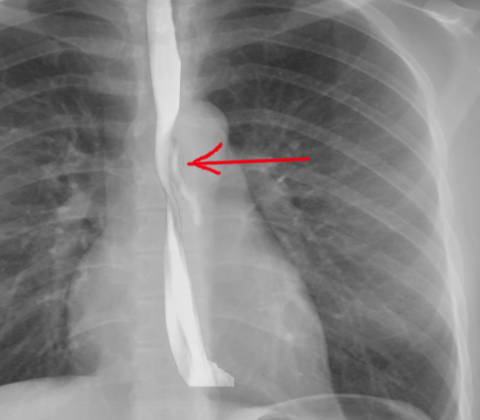

While a detailed discussion about diagnostic and radiographic findings is not covered here, it’s worth noting that a simple chest x-ray can detect signs of perforation in up to 90% of cases. One sign, subcutaneous emphysema takes about one hour to develop, while others, like a widened area in the middle of the chest or fluid accumulation around the lungs, can take several hours. This highlights the importance of reevaluating any patient whose initial tests were negative. The presence of an esophageal injury might only become detectable within the first 12 hours after the injury occurred.

Testing for Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)

Contrast-enhanced imaging of the throat area provides a detailed view of the structure and can effectively detect any perforations, or tears, in the esophagus, which is the tube responsible for moving food from the mouth to the stomach. Different types of contrast materials can be used for this, including water-soluble iodinated agents and water-soluble non-ionic agents. If the initial results don’t show a perforation but the suspicion remains high, barium sulfate will be used. However, because an injury could cause significant inflammation and fluid buildup in the esophagus, there is about a 10% chance that these images may not show a perforation when there is one.

A CT scan can be helpful in looking for esophageal perforations that weren’t seen in initial images. This technique can also tell the full extent of an injury, which is great for planning any necessary treatment steps. CT scans can be particularly useful in instances where there is still a high suspicion of injury despite a negative initial examination, or when patients are too sick, uncooperative or suffering neurological impairment to tolerate other tests. It can also be used in cases involving multiple injuries to vessels and the airway. In a CT image, signs of perforations may include fluid or gas buildup around the esophagus, thickening of the esophageal wall, and inflammation. CT scans can also identify collections of air or fluid in the space around the lungs or heart, which could suggest an esophageal perforation.

A test called a flexible esophagoscopy, which offers a direct view of the esophageal injury, can be particularly useful when trauma has caused a penetration, since it nearly always detects the injury and most of the time identifies it accurately. Its role in non-penetrating injuries isn’t as certain. This test is not recommended for smaller tears because the air used during the procedure could worsen the injury. Despite these limitations, performing an esophagoscopy can be justified in certain situations, including when there remains a suspicion of injury despite negative CT scans and initial imaging, or in patients with a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or ulcers.

Catching esophageal perforations early can improve the outcome and reduce complications. Because these injuries are rare and initial symptoms can be unclear, a high degree of suspicion, thorough physical examination, and detailed understanding of the mechanism of injury and relevant anatomy can optimize the management of these injuries.

Treatment Options for Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)

Esophageal injuries (EIs) are relatively rare, and treatment strategies often have to draw from individual case studies and experience, including situations where the injury wasn’t caused by trauma. The location of the injury greatly influences the treatment approach, with this review focusing mainly on injuries to the thoracic part of the esophagus.

Diagnosing and treating EIs sooner tends to lead to better patient outcomes. The esophagus doesn’t have a protective outer layer, making any repair work tricky. Ideally, the injury should be closed and drained as soon as possible, though the order of treatment may change if the patient has other severe injuries or medical conditions.

For those who aren’t showing many signs or symptoms and have the injury contained, non-operative management could be an option. This method could be suitable for patients who’ve experienced a delay in diagnosis due to mild symptoms or for those with significant injuries who’ve survived the initial shock and inflammation. For non-operative management to be considered, three criteria need to be met: the leak needs to be contained, the patient has minimal symptoms, and there’s little evidence of infection.

However, more often than not, EIs are considered surgical emergencies that require quick action. The extent of inflammation in the tissues around the injury will dictate whether primary repair or drainage is the best option. The level of contamination also significantly influences patient outcome, with surgical repairs still possible in delayed cases if there’s limited contamination.

The location of the injury will determine the surgical approach used. Injuries to the cervical esophagus are usually approach from the left neck to avoid damaging important structures. Injuries to the thoracic esophagus part are approached through a right posterolateral thoracotomy. Aside from the location of the injury, several surgical principles need to be followed, such as fully debriding the injury area, ensuring the repair is tension-free, reinforcing the repair with local tissue and muscle flaps, and ensuring proper drainage after the procedure.

For patients who can’t undergo primary repair or surgical diversion, wide chest drainage could control contamination. For certain cases, esophageal diversion and exclusion might be used to decrease the local flow of oral secretions and stomach contents at the injury site. In very severe cases where the patient has delayed diagnosis of the injury or other medical conditions, an esophagectomy (removal of the esophagus) may be considered, though this is quite rare.

After the operation, close monitoring and nutritional support are key to recovery. After 5 to 7 days post-operation, patients could undergo contrast swallow evaluations to check if healing is taking place.

As with any operation, the procedure carries potential risks such as the formation of fistulas (abnormal connections between different body parts), stricture formation, and the development of diverticulum (bulges) around the repair site.

In certain patients, esophageal stenting could be used to prevent leakage of food and liquid from the esophagus during recovery. While newer approaches are being studied, esophageal stents could offer several advantages, but it’s important to also ensure any contamination is controlled and adequately drained. Despite its promise, stenting does come with its own potential downsides such as discomfort and risk of stent movement.

What else can Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe) be?

A tear in the esophagus, also known as an esophageal perforation, is usually easy to diagnose if the patient has experienced a traumatic event or their symptoms start happening after an esophageal procedure.

However, if such a tear isn’t quickly recognized, the patient may experience chest pain, fever, or general signs of infection. These symptoms can overlap with several other health conditions, which makes the diagnosis more complex.

The conditions to be considered include, but are not limited to:

- Heart Attack

- Inflammation in the chest cavity between the lungs (mediastinitis)

- Heart inflammation caused by a virus (viral myocarditis)

- Inflammation or irritation of the esophagus (esophagitis)

- Blood clots in the lungs (pulmonary embolism)

- Ripping or tearing pain in the aorta, the main artery in the body (aortic dissection)

- Acid Reflux or heartburn (GERD)

- Inflammation of the stomach lining (gastritis)

What to expect with Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)

Esophageal injuries, which are damages to the food pipe, can happen from both blunt and sharp force impacts. Detecting these injuries would rely heavily on a strong suspicion by the doctor because many patients may not show any signs at first. Scanning technologies like CT scans are useful for identifying potential injuries, especially those due to puncture.

It’s crucial to identify these injuries as soon as possible to prevent further health complications that can lead to sickness and death. Two procedures, flexible endoscopy and contrast esophagography, can work together to give the most accurate diagnosis. The best treatment involves directly repairing the injury with sutures, strengthening the area with muscle flaps and ensuring proper discharge of fluids. In some cases, placing a stent can serve as a temporary solution until surgery or permanent management is possible. For nutrition, it’s best to use jejunostomy, a method where food is delivered directly to the intestines.

Generally, the impacts of esophageal trauma can be severe and could even cause death. Therefore, it’s important to have a strong suspicion, as well as a proactive treatment plan in place, to ensure the best possible outcome for the patient.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)

The biggest concern with esophageal perforation, a tear in the esophagus, is the development of mediastinitis and sepsis. These are serious conditions that can cause a lot of health problems and sometimes even death. If the tear isn’t found and treated, patients may also have issues like fluid buildup in the lungs (pleural effusions), abscesses, bleeding, lung collapse (pneumothorax), or other complications due to air and food leaking from the esophagus into the chest area.

Here are some possible complications:

- Development of Mediastinitis and Sepsis

- Fluid build-up in the lungs (Pleural Effusions)

- Abscess Formation

- Bleeding

- Lung collapse (Pneumothorax)

- Other complications due to leakage into the chest.

- Other health problems

- Potential death

Recovery from Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)

After surgery, the care needed for recovery can differ greatly from patient to patient. For example, people with a small, managed tear in their esophagus can often go home the same day they were admitted. However, those with larger areas of revived esophagus tissue might need to spend a longer time recovering in intensive care. These patients may also need help with feeding through a tube or directly into their bloodstream to get the nutrients they need.

Preventing Esophageal Trauma (Injury to the Food Pipe)

Most esophageal perforations, or tears in the food pipe, happen as a result of medical procedures or trauma, which makes prevention difficult. When people have a medical test known as an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), they should be made aware that there’s a chance the procedure could cause a tear in their food pipe. They should also be informed about what treatment methods would be used if this were to happen.