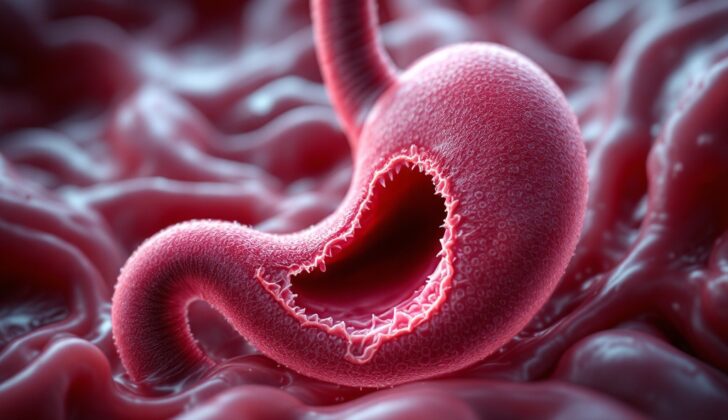

What is Gastric Perforation?

A puncture (or perforation) in the stomach happens when there’s a full-depth damage to the stomach’s wall. Remember, our stomach is entirely covered by a membrane called the peritoneum. So, a hole in the stomach’s wall would create an opening between the inside of the stomach and the abdominal cavity covered by this membrane.

If the hole happens suddenly, the body doesn’t have time to respond with inflammation to seal it off. This lets the stomach’s contents freely flow into the abdominal cavity, resulting in a condition called chemical peritonitis. If the hole developed slowly, the body might have time to respond with inflammation and contain the problem to a local area.

One might suspect a hole in the stomach based on someone’s symptoms, or it might only become clear with diagnostic imaging. These scans might show “free air” outside the stomach, which would signal a hole, and they’re usually done when investigating stomach pain or other symptoms.

Treatment for a stomach hole usually involves surgical repair. Most of the time, these holes are linear and found high in the stomach along the ‘greater curvature’ – this is the longest part or the outer bend of the stomach. The hole is usually closed with a patch made from omentum (a fatty, apron-like tissue in our abdomen) or the damaged area may be removed via a surgical procedure called a wedge resection.

What Causes Gastric Perforation?

Stomach perforation, or a hole in the stomach, can happen due to a variety of reasons. The most common cause is peptic ulcer disease; it’s a condition where sores develop in the lining of your stomach or upper part of your small intestine. Other reasons can include injuries, cancer, medical procedures, or specific stomach conditions, or it can happen on its own in newborn babies.

Peptic ulcer disease is the leading cause of a perforated stomach. But, with improvements in treatment, a perforated stomach only occurs in under 10% of people with peptic ulcers. This complication is more likely in older adults who take NSAIDs (a type of medicine for pain or inflammation) and those who drink excessive alcohol. If a stomach or duodenal ulcer creates a hole into the space inside your abdomen (named as peritoneal cavity), it initially causes a chemical inflammation, unlike inflammations caused by bacteria in the case of a more distal bowel perforation. If the ulcers on the back of your stomach perforate, they can leak stomach contents into a space called the lesser sac, which can limit the inflammation. These patients may have less severe symptoms.

Stomach perforation can also occur spontaneously, mainly in newborns in their first few days of life, leading to a condition called pneumoperitoneum, which is air or gas in the space inside your abdomen. But after the newborn period, such occurrences are rare and typically happen due to injury, surgery, ingestion of caustic substances, or peptic ulcer.

In case of traumas, stomach perforation usually happens due to penetrating injuries like gunshot or stab wounds or instrumentation of the stomach. Although severe blunt abdominal trauma can also lead to perforation and organ rupture. In cases of penetrating trauma, both front and back walls of the stomach may be injured, with the back wall always needing to be checked during surgery. A full and distended stomach can potentially lacerate or rupture if subjected to blunt trauma in the upper abdomen. However, due to its position inside the body, the stomach is relatively protected. It is the third most injured organ in the abdomen after the intestines and colon.

Cancers can lead to stomach perforation by directly penetrating and causing tissue death, or by producing blockages. Perforations associated with tumors can also happen spontaneously, after chemotherapy or radiation treatments, or due to medical procedures like stent placement for blocked exit of the stomach due to cancer.

Medical procedures can also injure the stomach, with upper endoscopy being the main cause of such injuries. The likelihood of stomach perforation increases with the complexity of the procedure and is less common in diagnostic than therapeutic procedures. The top of the stomach is most at risk because its wall is the thinnest. In total, perforation occurs in around 0.11% of rigid endoscopies and 0.03% of flexible endoscopies. Perforations due to medical causes are more frequent in patients who already have stomach conditions. Surprisingly, stomach rupture due to excessive inflating of the stomach can also happen during unrelated procedures like cardiopulmonary resuscitation and is typically located on the lesser curve, which is the least stretchable part of the stomach.

Endoscopy-related stomach perforations can be caused by various factors:

* Polypectomy (removal of polyps)

* EMR-ESD (types of endoscopic surgeries)

* Stretching of a narrowed connection between two organs

* Scope or pressure injuries

* Medications, other ingestions, foreign body: drugs or other substances causing injury to the lining of your stomach or foreign objects such as sharp items (e.g., toothpicks), food with sharp edges (e.g., chicken bones or fish), or a mass formed by the accumulation of indigestible material in your stomach (gastric bezoar).

Risk Factors and Frequency for Gastric Perforation

In kids, most cases of holes (perforations) in the stomach (gastric perforations) are due to injuries or trauma. The number of these cases is rising and includes both incidents caused by blunt force and objects piercing the body. In adults, ulcers used to be the usual cause. But, with the advent of new medicines like proton pump inhibitors, such perforations are now quite rare. It’s more common to see perforations in the first part of the small intestine (duodenum) than in the stomach. Also, about 30% of stomach perforations happen in conjunction with cancer.

Nowadays, a frequent cause of gastric perforations in hospitals is related to a procedure called an endoscopy. We don’t have the exact numbers because often the diagnosis is changed and reported as ulcer disease.

Signs and Symptoms of Gastric Perforation

Perforating injuries of the stomach can present in various ways depending on factors such as the size of the wound, blood loss, and the presence of other injuries. Symptoms can range from mild localized pain to signs of peritonitis and shock.

It is crucial to take a detailed history from patients experiencing neck, chest, and abdominal pain. This history should cover previous episodes of similar pain, any medical procedures they’ve had (such as the insertion of a nasogastric tube or endoscopy), past trauma or surgeries, any known malignancies, possible swallowing of foreign bodies, underlying medical conditions like peptic ulcer disease, and medications they may be taking including NSAIDs and glucocorticoids.

- Refusal to eat

- Vomiting

- Decreased activity

- Sudden onset of abdominal distention and pain

- Ileus

- Respiratory distress

- Fever

- Vomiting of blood (hematemesis)

- Passing of bloody stools (hematochezia)

Most individuals with a perforation report a sudden severe abdominal or chest pain and can often pinpoint the exact moment the pain started. Severe chest or abdominal pain following medical procedures should be suspected as a possible gastric perforation. Those taking immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory medications may experience less pain and tenderness due to a dampened inflammatory response. Some may present later with complications like sepsis. Irritation of the diaphragm may lead to pain radiating to the shoulder and sepsis may be the first sign of a perforation. Certain groups of patients including the elderly, frail, and immunosuppressed may struggle to wall off a stomach perforation, leading to sepsis.

Physical examination should include vital signs and a thorough examination of the abdomen. Most patients will have a rapid heart rate (tachycardia), rapid breathing (tachypnea), fever, and generalized abdominal tenderness. It’s likely they will have absent bowel sounds and signs of peritoneal irritation like rebound tenderness and guarding.

Testing for Gastric Perforation

If a doctor suspects that your abdomen may have trapped air or gas, tools for getting a closer look, like X-rays, and other images can help with the diagnosis. A sign suggestive of this condition could be that there is no air-liquid level in your stomach when viewed in a horizontal X-ray and there is less gas in your lower gut.

The process begins with plain X-rays (also known as films), which can detect trapped gas outside the gut between 50% to 70% of the time. Ultrasound imaging has also been examined and appears to be excellent at finding air in the abdominal cavity. However, the best imaging tool to use is the CT scan, as it is very accurate at detecting gas.

A CT scan can show a number of signs that may suggest a rupture in the organ wall, including:

- Gas in the abdominal cavity

- Gas in the tissue that connects and supports your abdomen

- A break in the wall of an organ

- A contrast dye used in the imaging procedure leaking outside the gut

- Free fluid in the abdominal cavity

- Contrast dye leaking out of blood vessels

- Swelling or fluid in the organ wall

- Blood clot in the abdominal cavity.

In complex cases, the doctor might need to perform a surgical procedure called a diagnostic laparoscopy to figure out what’s causing the problem and collect fluid for further testing.

Treatment Options for Gastric Perforation

If you have a stomach perforation, the first steps in treating it are usually providing extra hydration and oxygen, giving IV fluids, and starting a course of antibiotics that can fight a wide variety of infections. A tube will be inserted through your nose and into your stomach to help vent it. You may also be given pain relief and medications to lower stomach acid as needed. A catheter will be inserted to monitor how often and how much you urinate as a clue to your body’s hydration status.

In almost all cases, surgery is necessary to repair a perforation in the stomach. Whether this is performed as an open surgery (a traditional larger incision) or laparoscopically (small incisions using a camera) will depend on your specific case. It’s important to start this treatment as soon as possible to prevent complications.

If your stomach perforation was due to a traumatic injury like a gunshot or stab wound, your care team will closely check your stomach, as both the part that faces the front of your body and the part that faces the back of your body could be injured. In some cases, only the back side of your stomach could be injured if your stomach was very full at the time of the incident, tilting it to face the front.

Your surgical team has several strategies available to repair the injury:

Primary repair: This is typically the first option for most traumatic perforations. The injury is stitched up.

Graham patch repair: In this technique, a piece of healthy omental tissue rich in blood supply is used to plug the injury.

Modified Graham patch repair: The team will stitch up the injury first, then apply a tissue patch.

Wedge resection: If the perforation is located on an area of the stomach that is distant from essential points and is easily accessible, the entire perforated region may be removed and the stomach is then stitched back together.

Depending on the location and the extent of the injury, your surgeons might need to rebuild part of your stomach or small intestine using one of the following techniques:

Billroth I: The remaining part of the stomach is connected directly to the first part of the small intestine (duodenum).

Billroth II: The stomach is connected to the middle part of the small intestine (jejunum) after excluding the first part.

Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy: A new connection is made between two parts of your small intestine, forming a Y shape, and then attaching the upper part to your stomach.

What else can Gastric Perforation be?

The list of conditions that could potentially cause sudden abdominal pain, similar to a stomach perforation, includes but is not limited to:

- Peptic ulcer

- Duodenal ulcer

- Biliary disease (problems with the gallbladder or bile ducts)

- Splenic infarction (a condition where the spleen doesn’t get enough blood)

- Embolic mesenteric insufficiency (a condition where the intestines don’t get enough blood)

- Gastritis (inflammation of the stomach lining)

- Esophageal perforation (a hole in the esophagus)

- Rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (a serious condition where the large blood vessel that supplies blood to the abdomen, pelvis, and legs bursts)

What to expect with Gastric Perforation

In the last thirty years, there has been a significant improvement in the health outcomes of patients with gastric perforations. However, late diagnosis and treatment can still be fatal. There are several factors that increase the risk of death in these individuals:

- Having other serious health conditions

- Being of advanced age

- Being malnourished

- Experiencing complications

- The type and location of the perforation in the stomach

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Gastric Perforation

After experiencing a gastric perforation, a patient may face several complications. These could include:

- Infection of the wound,

- Severe body-wide infection known as sepsis,

- Malnutrition,

- Failure of multiple organs,

- Adhesions (bands of scar tissue) that cause the intestine to stick together leading to blockages,

- Confusion or disordered thinking (known as delirium).

The likelihood of these complications happening can become higher if the patient is:

- Older in age,

- Experiencing dementia,

- Suffering from sepsis,

- Having issues with their body’s electrolyte and metabolic balance,

- Lacking enough oxygen, known as hypoxia,

- Facing complications during their operation.

Recovery from Gastric Perforation

Patients who visit the hospital shortly after their body undergoes a “perforation” or a hole made by injury or disease, usually have a good recovery. They can start eating one or two days after surgery and can leave the hospital once they can handle sufficient food intake. However, patients who visit the hospital later while experiencing sepsis, a very serious infection, or those with multiple other health conditions, may take longer to fully recover. They could also have to spend some time in the Intensive Care Unit to manage and treat their severe infection effectively.

Preventing Gastric Perforation

The most common cause of holes or tears (perforations) in the stomach lining is an illness called peptic ulcer disease. To reduce the risk of these perforations, patients with this condition should regularly take a type of medication called a proton pump inhibitor, which helps reduce stomach acid. It’s important for patients to take this medicine routinely, not just when they have symptoms. If a patient tests positive for an infection called H pylori, it’s also crucial to get rid of this infection, as it also plays a role in causing stomach ulcers.

During routine procedures that look inside the stomach (endoscopies), doctors have to be mindful of a few things to lessen the chance of perforations:

– Avoid looping the endoscope (the thin tube used for the procedure) excessively in the stomach. Pressure in the left upper belly or the use of an overtube (a larger tube to guide the endoscope) can help with this.

– If the doctor needs to remove a large growth that sits flat on the lining of your stomach (sessile lesion), injecting fluid underneath this area first can help make the procedure safer.

– If the lesion is below the lining of the stomach (subepithelial lesion), an ultrasound of the stomach wall (EUS) should be done first before attempting to remove it.

– Proper instruction and application of a cap-assisted EMR kit can help. This kit provides a cap that can be attached to the endoscope and is used for the safe removal of growths in the stomach.

– When widening a tight or narrow opening (stricture) from the stomach to the small intestine, the use of X-rays (fluoroscopy) may be considered to help guide the procedure.

– In some cases, pumpment of carbon dioxide (instead of air) into the stomach (insufflation) may be preferred to reduce discomfort and other complications.