What is Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation)?

Gastritis is a condition where the lining of the stomach, called the gastric mucosa, becomes inflamed. This inflammation can be revealed through endoscopy or radiology tests revealing abnormal appearances of the stomach lining. Gastritis can be triggered by an infection or a reaction of the body’s immune system, with physical signs of inflammation in the stomach lining helping diagnose the condition.

Gastropathy is a similar condition but involves problems with the stomach lining without inflammation. It is often associated with damage to the stomach lining’s cells, followed by a healing process. Gastritis and gastropathy can sometimes occur together. For example, in a patient with gastritis, there may also be signs of damage to the stomach lining, while in someone with gastropathy, there may be evidence of inflammation.

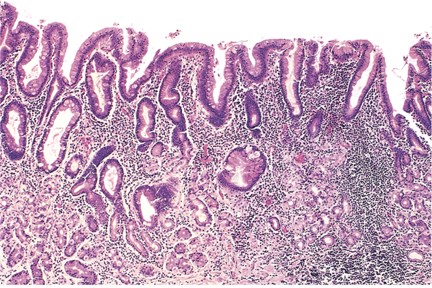

Gastritis can be sorted by several factors, including how long the inflammation has been present (acute or chronic), the specific features of the inflammation seen in tissue samples, or its cause. Despite the lack of a universally accepted way of classifying gastritis, understanding the tissue signs and causes of different forms of gastritis aids in comprehending their patterns and classifications. Proper evaluation of tissue samples is also crucial in shaping treatment plans for this disease.

This summary provides insights into various appearances of gastritis under microscope examination, evaluates their potential impact on health outcomes, and explains recommended management tactics for these conditions by healthcare guidelines. The primary aim of this topic is to enhance healthcare providers’ skills, thereby improving patient results.

What Causes Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation)?

Acute gastritis is a short-term swelling of the stomach lining, often caused by stress or injury to the protective layer of the stomach. Many factors can trigger this, including kidney disease, restricted blood flow, shock, harmful substances, medications, radiation, major injuries, severe burns, infections, bile reflux, or blood poisoning. Certain viruses can also cause a brief bout of gastritis. The inflammation could result from a reduction in protective mucus secretion in the stomach, disruption of the protective barrier, or decreased blood flow to the stomach wall.

Chronic gastritis is a persistent inflammation of the stomach lining and comes in two forms: atrophic (tissue loss) and non-atrophic. This is most commonly caused by a Helicobacter pylori infection, which initially begins in a non-atrophic form. But without adequate treatment, this form of chronic gastritis can transform into atrophic gastritis. Autoimmune gastritis is often thought of as the dominant reason for atrophic gastritis. In this case, the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks healthy cells in the stomach lining, causing ongoing inflammation and tissue loss. Some people have antibodies reacting against normal stomach components. There’s still uncertainty if autoimmune gastritis is an independent condition or if an H Pylori infection triggers an immune reaction in some individuals.

Reactive gastritis shares many triggers with acute gastritis, like particular drugs, alcohol, radiation, and bile reflux. These factors tend to cause minor inflammation and lesions in the stomach lining. You might not have symptoms, and the condition is usually found during an endoscopy often showing several erosions or ulcers. Medications used to treat different cancers have led to increased cases of reactive gastritis, though it remains relatively uncommon.

The Sydney System, introduced in 1990, is a widely used method for classifying the characteristics of gastritis found in endoscopic biopsies. It provides information about the type, severity, and spread of the stomach disease. The label includes the inflammation’s location, whether it’s restricted or involves the entire stomach. If the cause is known, it’s included as a prefix, like ‘autoimmune corpus gastritis’ for autoimmune-related inflammation. There are five additional variables that offer more information: the longstanding nature of inflammation, gastritis activity, abnormal change of cells, the degree of tissue loss, and whether H pylori organisms are present. Unfortunately, this system doesn’t provide a means to predict future changes in the disease.

Another approach to classifying gastritis takes into account the cause and the persistent nature of the inflammation. This classification divides gastritis into three main categories: acute, chronic, and ‘special’. The ‘special’ subtypes include gastritis of unknown causes.

‘Infectious gastritis’ is prevalent due to the widespread H pylori infection. Other bacterias, viruses, parasites, fungi, and severe infections can also cause gastritis. ‘Special’ gastritis includes granulomatous gastritis found in patients with Crohn’s disease and sarcoidosis, lymphocytic gastritis, collagenous gastritis, and eosinophilic gastritis with unclear causes. There is a known connection between lymphocytic and collagenous gastritis with celiac disease, while eosinophilic gastritis has a strong association with allergy conditions and food allergens.

At the Kyoto Consensus Conference, an exhaustive classification of gastritis based on causes was presented. This included autoimmune gastritis, various forms of infectious gastritis, drug-induced gastritis, radiation gastritis, alcohol gastritis, chemical gastritis, gastritis due to duodenal reflux, and gastritis connected with other conditions like sarcoidosis, vasculitis and Crohn’s disease.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation)

Finding out how common acute gastritis is can be difficult because it’s often caused by things like enterovirus infections that are typically mild and go away on their own, so they don’t get reported. Other causes, such as sepsis, ischemia, and caustic injury, don’t happen as often as chronic gastritis related to H pylori or chronic autoimmune gastritis. Recent data shows about 25% of people worldwide have chronic autoimmune gastritis. Also, people with an H pylori infection have about 2.4 times higher risk of developing this condition.

In Western countries, the rate of gastritis caused by H pylori is going down, but the rate of autoimmune gastritis is going up. Autoimmune gastritis is more common in women and older people, affecting about 2% to 5% of these populations. However, the data might not be very reliable.

Gastritis related to chronic H pylori is still common in developing countries. Among children in Western countries, about 10% have an H pylori infection, but in developing countries, the rate can be as high as 50%. The infection rate in developing countries can be quite different depending on the area and the socioeconomic conditions – it’s estimated to be around 69% in Africa, 78% in South America, and 51% in Asia.

How common H pylori infections are worldwide depends on factors such as hygiene practices in the family, overcrowding in households, and dietary habits. The infection is currently considered to usually start in childhood, which then affects the number of cases in the community as a whole.

- The estimated rate of atrophic gastritis in the US can be as much as 15%.

- This rate might be higher among groups that have a higher baseline rate of H pylori infection, such as non-White racial and ethnic minorities and first-generation immigrants from countries where H pylori infections are common.

- Atrophic gastritis not related to H pylori is pretty rare, with an estimated rate of 0.5% to 2%, but this might be an overestimate.

- The rate of this condition is higher among patients with other autoimmune diseases; it’s estimated that up to one-third of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease also have autoimmune gastritis.

- Unlike gastritis associated with H pylori, there aren’t any racial or ethnic patterns in autoimmune gastritis incidences.

Signs and Symptoms of Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation)

Gastritis, which is an inflammation of the stomach lining, can be a bit tricky to diagnose just based on the symptoms. These symptoms may include upper abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, and vomiting. Interestingly, the severity of the disease doesn’t always match the intensity of the symptoms. A more precise diagnosis often requires an endoscopy or a tissue examination.

Gastritis associated with H pylori bacteria often has no symptoms and may slowly progress to serious complications, such as stomach cancer. Not everyone who has stomach pain or discomfort (“dyspepsia”) is infected with this bacteria. On the other hand, some people may suddenly experience dyspepsia due to an initial infection with H pylori, but such cases usually get better on their own. If patients with chronic stomach discomfort get better after successful treatment for the H pylori bacterium, it’s believed that their symptoms were caused by the bacteria. However, it may take up to six months for the symptoms to improve after treatment.

If the dyspeptic symptoms continue even after successful treatment, it could be due to “functional dyspepsia”. This is where there are chronic symptoms, like fullness after eating, early feeling of being full, upper abdominal pain, or a burning sensation, without any detectable abnormalities from an upper endoscopy.

Autoimmune gastritis is another variant that is usually symptom-free. People with this condition usually seek medical help when they are diagnosed with certain types of anemia. Although it’s rare, those suffering from this type of gastritis might experience symptoms such as post-meal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, or brooding stomach pain. Often, autoimmune gastritis is found in people dealing with other autoimmune diseases including thyroid conditions, Addison disease, and type 1 diabetes, among others.

Symptoms like early fullness after eating and discomfort following meals can be indications of autoimmune gastritis, especially in younger patients. The prevalence of such discomfort worldwide makes it crucial to interpret these symptoms correctly.

Testing for Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation)

The primary method for diagnosing gastritis, a condition in which the stomach lining gets inflamed, is by examining tissue samples from the stomach. Even though understanding your medical history and performing laboratory tests can be helpful, the most reliable methods for diagnosing gastritis are endoscopy and biopsy. These allow doctors to assess the extent of the inflammation, how severe it is, and what might be causing it.

Patients suspected of having functional dyspepsia, a type of uncomfortable digestion, usually do not need an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for diagnosis. However, it’s important to check for an H pylori infection, a common cause of gastritis.

Let’s say someone has new symptoms of dyspepsia. If they’re also experiencing other concerning signs like unexplained weight loss, abnormal bleeding, problems swallowing, presence of an abdominal mass, fever, persistent vomiting, or they have a family history of esophageal or stomach cancer, doctors usually suggest further testing. This could include an upper gastrointestinal endoscopic evaluation and a detailed examination of tissue samples collected during this procedure. However, if a patient is under the age of 60 and has dyspepsia but no family history of stomach cancer, it’s generally not recommended to perform an endoscopic evaluation just to rule out stomach cancer.

Testing for H pylori is usually recommended and involves thorough examination. This often involves using the urea breath test or the H pylori stool antigen test. In the absence of certain complicating factors, such as recent stomach surgery or use of antibiotics or proton pump inhibitors (PPI), the urea breath test is generally considered more accurate than other noninvasive tests. Importantly, one positive result from these noninvasive tests can be enough to start treatment for eradication of H pylori in patients with dyspepsia, even if they don’t have any alarming symptoms.

Noninvasive testing can also confirm whether treatment has successfully eliminated H pylori. This should be done 4 to 6 weeks after completing antibiotic or PPI therapy. For patients aged 60 or older with dyspepsia, an endoscopy and histological evaluation is usually suggested for assessing gastritis.

The diagnosis of a type of gastritis known as autoimmune gastritis involves a few different tests. These include checking for atrophic gastritis in the body of the stomach and fundus, the presence of specific autoantibodies, and levels of substances known as serum pepsinogen I and the ratio of pepsinogen I to pepsinogen II.

Recognizing a condition called pernicious anemia, which often occurs along with atrophic gastritis, is important. This is characterized by the presentation of antibodies against intrinsic factor or parietal cells. Even though a new diagnosis of pernicious anemia should prompt a stomach endoscopy to check for atrophic gastritis, it’s important to remember that these antibodies can also show up in individuals with an H pylori infection and other autoimmune conditions.

From an endoscopic perspective, atrophic gastritis can usually be identified by certain visual changes in the stomach lining. This includes paleness, noticeable thinness, disappearance of gastric folds, and more. Special imaging techniques can provide a detailed view of these changes, which can then be confirmed through biopsy and histopathological analysis.

In diagnosing atrophic gastritis, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) adherence to The Sydney protocol is advisable. This protocol involves taking tissue samples from five specified locations inside the stomach. Once atrophic gastritis is diagnosed, testing for H pylori is usually recommended if it hasn’t been done yet. If this test comes out positive, treatment for eradication should initiated and followed by subsequent testing to confirm the success of treatment.

Additional tests may be required in some cases. This can include checking antibody levels, evaluating dietary vitamin levels, especially vitamin B-12 and iron, which can be deficient in those with advanced atrophic gastritis. It’s usually helpful to schedule repeated endoscopic procedures every few years in these individuals to keep track of any possible development of stomach cancers.

Where accessible, testing for pepsinogens I and II can give valuable insight when assessing atrophic gastritis patients. In areas with high rates of stomach cancer, certain levels of these substances in the blood can indicate severe atrophy with high sensitivity and specificity.

Treatment Options for Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation)

If someone has certain signs of gastritis (an inflammation, irritation, or erosion of the lining of the stomach), they are generally recommended to receive treatment to get rid of a type of bacteria called H pylori. This treatment is also the initial option for people with discomfort or pain in their stomach (known as dyspepsia) who are found to have an H pylori infection. Furthermore, this treatment is suggested for patients showing signs of peptic ulcer disease, functional dyspepsia, a particular blood disorder (Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura or ITP), unexplained iron-deficiency anemia, or if they are about to start long-term treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), especially if they’ve had peptic ulcer disease in the past. Even though this treatment might not relieve symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia, it can greatly lower the risk of them developing peptic ulcer disease.

Eliminating H pylori from patients with chronic gastritis that hasn’t resulted in atrophy (a reduction in the stomach’s ability to function), is strongly encouraged. This is because it can help the stomach to heal and lower the risk of stomach cancer. For patients where atrophy has occurred, targeting H pylori might slightly improve the condition and possibly reduce the risk of stomach cancer. For patients where the stomach lining has started to be replaced by abnormal cells (intestinal metaplasia), getting rid of H pylori might stop this from getting worse but it doesn’t necessarily lower the risk of stomach cancer.

In cases where patients show signs of chronic gastritis but test negative for H pylori, there aren’t standard guidelines for managing their condition. Something that has proved successful in relieving symptoms is the use of Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs). These drugs are recommended for people under 60 with dyspepsia who either test negative for H pylori or still have symptoms despite treatment to eradicate H pylori. If these patients don’t find relief from these treatments, they could be considered for treatments that either help the stomach empty more quickly (prokinetic therapy) or a certain type of antidepressant (tricyclic antidepressants). However, the quality of evidence to support this approach varies from low to moderate.

Currently, there’s no definitive treatment for atrophic gastritis. The main focus in treating this condition is to assess the severity of the disease and the risk of stomach cancers. There are systems, such as the Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment (OLGA) and Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM), that are recommended for this. Patients at a high risk of stomach cancer are advised to have regular checks for early signs of cancer, as the chances of successful treatment are much higher if detected early.

The level of inflammation or gastritis is measured by assessing numbers of certain cells in the stomach lining using samples taken from a biopsy. A grading system is then used based on these counts to determine the severity of the gastritis. The OLGA and OLGIM systems also take into account any changes from normal to abnormal cells in the stomach lining, which are scored based on how much of the stomach lining is affected. Although the OLGIM method is easier for different observers to agree on, it can miss people at high risk. Having an endoscopy every three years is recommended for those identified as high risk, along with consideration of other factors such as a family history of gastric cancer, history of H pylori infection, smoking, and diet.

What else can Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation) be?

When a doctor is trying to diagnose gastritis – a condition that inflames your stomach lining – they have to consider several other health issues that can cause similar symptoms. Here are some potential conditions a doctor might consider:

- Dyspepsia (indigestion)

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Stomach cancer

- Cholecystitis (inflammation of the gallbladder)

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (a rare condition involving the pancreas and stomach)

- Pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas)

- Myocardial ischemia (reduced blood flow to the heart)

- Stomach lymphoma (a type of cancer in the stomach’s lymphatic tissue)

- Celiac disease (an autoimmune disease triggered by gluten)

- Multiple endocrine neoplasias (a group of disorders affecting the body’s endocrine system)

To reach an accurate diagnosis, the doctor needs to carefully consider these alternatives and perform the necessary tests.

What to expect with Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation)

The outlook for people with gastritis varies and depends on the type, the underlying cause, and the patient’s individual characteristics. If correctly managed, most cases of gastritis can be effectively handled, and the risk of complications can be lowered. If acute gastritis, due to lack of blood supply or because gas has formed inside the stomach wall, isn’t treated quickly, it can have poorer outcomes.

However, the outlook for atrophic gastritis, a type where the stomach lining gets thinner, depends on how bad the condition is. Research shows that people with atrophic gastritis are more likely to develop stomach cancers. Doctors aim to catch these complications early, which is why they focus on understanding the severity of the condition. One study shows that each year, 0.25% of people with atrophic gastritis develop stomach cancer, and 0.68% develop a certain type of cancerous tumor in their stomach. Another study shows that the occurrence of a specific type of stomach cancer is 14.2 out of 1000 people with a type of atrophic gastritis caused by the immune system, compared to only 0.073 in a general population. The pattern, extent, and the severity of this thinning in the stomach are the key factors in predicting an increased risk of cancer. The value of predicting the disease’s prognosis from different types of changes to the stomach lining seems to be limited.

Meanwhile, research from different parts of the world has variance in the effectiveness of a treatment for H pylori, a bacteria linked to gastritis and stomach ulcers, in reducing the risk of cancer due to variations in risk from one place to another. However, it is generally accepted that successful treatment improves the outlook. A comprehensive review indicates a one-third decrease in the risk of cancer after successful treatment. The research shows a scenario called a “point of no return,” with lower cases of stomach cancer in patients who were carriers of H. pylori but did not have pre-cancerous conditions, such as atrophic gastritis or changes to the stomach lining.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation)

The bacterial infection, H pylori, in the stomach (referred to as H pylori-induced gastritis) can result in several health issues. These can include peptic ulcer disease, immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), low iron levels (iron-deficiency anemia), and deficiency of vitamin B12. Recent studies have also suggested that it might be associated with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. This is believed to be due to molecular mimicry and a constant state of low-level inflammation. However, there is not enough scientific evidence yet to say for sure that gastritis can cause these metabolic conditions.

The highest risk from gastritis is stomach cancer, which is linked with severe chronic inflammation of the stomach lining called atrophic gastritis. If you have atrophic gastritis and changes in the lining of your digestive system (gastrointestinal metaplasia), your risk for stomach cancer is much higher compared to people with gastritis but without these conditions. The more severe your gastritis, the higher your risk for stomach cancer – people with moderate atrophic gastritis have about a 1.7% risk while people with severe atrophic gastritis have a 4.9% risk.

The inflammation caused by an H pylori infection can also lead to a type of blood cancer known as extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Research shows that the cancer cells actually grow from B-cell clones at the site of chronic inflammation. Other studies have found a correlation between the bacterial infection and a condition called gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. The bacteria might even be culpable for early-stage gastric B-cell lymphoma – studies cited instances where this type of lymphoma disappeared after H pylori was eliminated from the body.

In addition to all this, atrophic gastritis can cause tumors in your stomach’s nerve cells which are known as gastric neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). The seriousness of these tumors depends on their size, how fast they are growing, and how far they have spread. Small NETs can usually be removed with endoscopy and tend not to spread. However, larger tumors that are more than 2 cm have been linked with a nearly 20% rate of spreading to other parts of the body.

Both H pylori and autoimmune-caused gastritis can lead to anemia due to iron deficiency. This is especially pronounced in individuals whose iron deficiency is idiopathic, or without a known cause. Certain medical guidelines even recommend screening and treating H pylori in patients with recurring or treatment-resistant iron-deficiency anemia who have undergone normal upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies.

Lastly, ITP, or a decrease in blood platelets, is another possible complication of gastritis. If you have ITP, medical guidelines suggest testing for H pylori.

Preventing Gastritis (Stomach Inflammation)

Teaching patients about their health is key in dealing with gastritis, as it allows people to take steps in preventing or handling this condition effectively. In cases where gastritis is caused by the H pylori bacteria, it becomes especially important to educate patients on several points

Firstly, patients should be informed how the H pylori bacteria is transmitted, which is usually through close contact with another person. It’s also vital patients understand the importance of maintaining good hygiene to lower the chances of getting infected.

Secondly, patients need to know how to protect themselves. This involves avoiding food and water that might be contaminated since this can greatly decrease the chances of getting an H pylori infection.

Lastly, when a patient is diagnosed with H pylori infection, they should complete the entire course of antibiotics prescribed by their doctor. Following this step is essential to fully get rid of the bacteria and lower the chances of the infection coming back.

For those with gastritis due to an autoimmune condition and lack of vitamin B12, it’s vital to teach the importance of regularly taking vitamin B12 supplements. This helps prevent anemia and other related problems. Patients should also be informed about potential gastritis complications, such as bleeding or peptic ulcers, and why it’s crucial to seek medical help immediately if these issues come up.

Moreover, patients should understand the possible risks related to the long-term or excessive use of certain medications like NSAIDs and aspirin, which can cause or worsen gastritis. This understanding can help patients make educated choices about their medication and take steps to lessen the chances of their gastritis getting worse.

Recently, there’s been a push for mass testing for H pylori, followed by treatment to eliminate the bacteria. National guidelines for these screenings vary from one country to the next. In areas where this infection is not common, most guidelines do not advise mass testing. In contrast, a ‘test-and-treat’ approach is recommended for communities at a high risk of stomach cancer and is generally cost-effective in these areas. An extensive test-and-treat trial conducted in a high-risk region of rural China yielded promising results, but its long-term efficacy in preventing stomach cancer is still under review.

A key concern related to these screening programs involves the risk of resistance to antibiotics. For example, a study found that using the antibiotic clarithromycin, for just a week to treat H pylori, increased the resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae, a type of bacteria that causes not only pneumonia but also more serious infections. The use of antibiotics commonly used for treating life-threatening infections to treat H pylori in gastritis cases is strongly advised against. When strategizing public health campaigns to eliminate H pylori, it’s recommended to use other medicines like bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole. The antibiotic rifabutin may also be considered, as its short-term use is unlikely to contribute significantly to resistance to treatment for bacterial infections.