What is Necrotizing Enterocolitis?

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a very serious disease that primarily affects newborn babies. This condition can be extremely dangerous, with a survival rate of only 50%. NEC develops when the baby’s intestines become inflamed, allowing bacteria to invade and harm cells, causing cell death. This can result in severe damage to the colon and intestines, known as necrosis.

If NEC gets worse, it can cause a hole, or perforation, in the intestine. This can lead to serious complications such as inflammation of the membrane lining the abdomen (peritonitis), widespread bacterial infection in the body (sepsis) and, in the worst-case scenario, death. The symptoms of NEC, like poor feeding, vomiting, tiredness, or tenderness in the abdomen, can be quite common in newborns. Because of this, doctors are extra vigilant when newborns show these symptoms, always keeping in mind that they could indicate the presence of this dangerous disease.

What Causes Necrotizing Enterocolitis?

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a condition that happens when bacteria invade the wall of the intestine. This invasion leads to inflammation and the breakdown of the cells in the intestine wall. If this condition isn’t spotted and treated, a hole could form in the intestine, allowing its contents to spill into the abdomen. This can lead to an infection of the abdomen, also known as peritonitis.

The exact reasons behind why this bacterial invasion occurs are still not fully understood. In premature babies, a possible factor could be immaturity of the digestive system. This might be contributing to the development of necrotizing enterocolitis in these cases.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a serious disease found mainly in newborn babies. It poses a big threat especially to those in the neonatal intensive care unit because it targets their gastrointestinal tract, which is a vital part of the digestive system. The disease usually shows up in the second or third week after birth.

- Several factors may increase the risk of getting this disease, but being born prematurely, having a low birth weight, and being fed with formula, especially high-osmolarity formulas, are the main ones.

- Genetic factors may also contribute to the risk.

- The number of babies affected by this disease differs around the world; it varies between 0.3 to 2.4 infants for every 1000 live births.

Most of the babies affected by this disease, about 70%, are premature babies born before 36 weeks gestation. It’s also responsible for about 8% of all admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit. The disease can be lethal in some instances, with death rates ranging from 10% to 50%. In severe cases where the disease causes perforation, sepsis, and inflammation in the peritoneum (a membrane which lines the inside of the abdomen), it could even lead to a 100% mortality rate.

The disease, while mainly found in premature infants, can also occur in full-term babies. When it occurs in full-term babies, it usually happens within the first few days after birth and often happens in conjunction with a lack of oxygen supply event, like a cyanotic congenital heart defect.

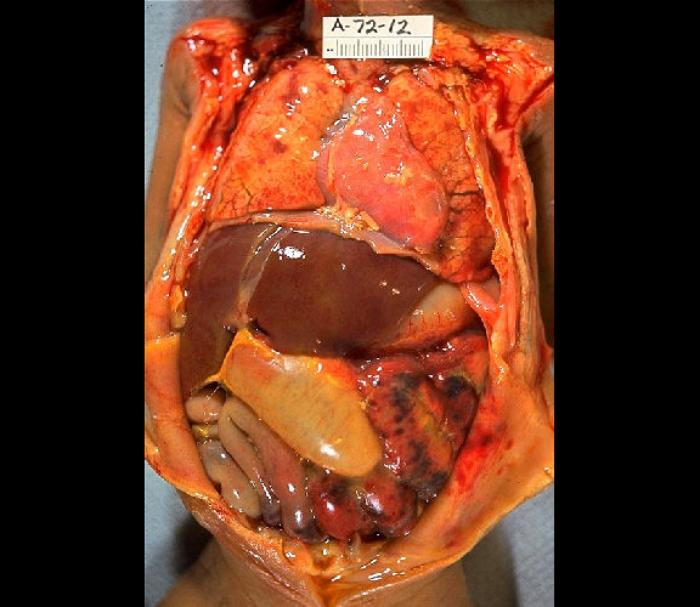

abdominal distention, necrosis, hemorrhage, and peritonitis due to perforation.

Signs and Symptoms of Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a condition with symptoms that can vary greatly and are often not specific or easy to identify right away. Parents of children with this condition may notice a decrease in their child’s overall activity and an increase in fatigue. They may also find that their child is not eating as much, is vomiting, has diarrhea, or their belly is noticeably larger. Another sign is blood in the stool. If the disease worsens, the child may display signs of respiratory failure or circulatory collapse, such as looking bluish or not responding.

Upon a doctor’s physical examination, they may observe a larger belly, sensitivity in the abdominal area, visible intestinal loops, a decrease in bowel sounds, a possible abdominal mass, and redness of the abdominal wall. There might also be signs of systemic issues such as respiratory failure, a breakdown of the circulatory system, and decreased blood flow to the child’s limbs.

- Decreased activity and fatigue

- Decreased appetite

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Increasing abdominal size

- Blood in the stool

- Respiratory failure symptoms (like bluish skin)

- Signs of circulatory collapse (like not responding)

Testing for Necrotizing Enterocolitis

The primary test used for diagnosing necrotizing enterocolitis, a severe intestinal disease, is an abdominal X-ray series. This usually includes two specific types of X-rays – one taken from the front to the back (anterior-posterior view) and one taken from the side while you’re lying on your left side (left lateral decubitus view). These X-rays help doctors observe the state of your intestines. If they see swollen loops of intestine, air within the bowel wall (known as pneumatosis intestinalis), and air in the portal vein (a major vein that brings blood to the liver), then the diagnosis is typically necrotizing enterocolitis.

Pneumatosis intestinalis, the condition where there are small amounts of air within the bowel wall, is a certain sign of necrotizing enterocolitis. Also, while not always present, air in the portal vein is viewed as a bad sign when found. Lastly, if there’s free air in the abdomen, this usually indicates the intestine has ruptured or perforated.

An abdominal X-ray doesn’t only help in diagnosing the disease, it’s also useful for tracking how the disease is developing over time. Typically, these X-rays are repeated every six hours until the disease has been adequately treated.

Blood tests can also provide some insight, but these are usually limited and not as specific. For instance, if your white blood cell count is less than 1500 per microliter, this could indicate an infection is present. Meanwhile, a full metabolic panel might reveal low levels of sodium (hyponatremia) and bicarbonate (useful in buffering acids in the body). In many cases, blood cultures do not typically show anything. A breath hydrogen test could be positive, but this test is rarely done.

Treatment Options for Necrotizing Enterocolitis

If a patient, especially a child, is critically ill, the primary focus should be on stabilizing their basic life functions: their airway, breathing, and blood circulation. This may require the patient to receive fluids intravenously to correct low blood pressure or even be put on a mechanical ventilator if they’re not able to breathe on their own. If the patient’s situation worsens drastically, the healthcare provider would follow the guidelines of Pediatric Advanced Life Support to help restore their vital functions.

A specific disease that can arise, especially in infants, is necrotizing enterocolitis, a severe condition where portions of the bowel undergo tissue death. If this disease is suspected, the initial treatment approach includes stopping all food directly into the stomach or intestine and inserting a nasogastric tube. A nasogastric tube is a thin, flexible tube inserted through the nose, down the esophagus, and into the stomach to relieve pressure in the dilated bowels.

While the patient can’t consume food by mouth, they should be given antibiotics via an intravenous line to fight against a broad spectrum of bacteria. A recommended antibiotic regime might consist of ampicillin, gentamicin, and either clindamycin or metronidazole. Additionally, the patient would receive all necessary nutrition through their vein via a process known as total parenteral nutrition. If this non-surgical treatment works, the infant can resume eating once the infection signs disappear. This process can take several days or up to a week in some cases. The return of normal bowel movements is an excellent sign of recovery.

However, if an infant’s condition worsens or if the bowel ruptures, or if the non-surgical treatment doesn’t result in any improvement, surgery may be required. The primary surgical procedure usually involves making a small cut in the abdomen (laparotomy) and removing only those parts of the intestines that are critically damaged or ruptured. The goal here is to keep as much of the healthy intestines intact as possible.

For extremely ill or small patients who might not tolerate surgery, an alternate approach may involve the insertion of a peritoneal drain to remove free air and fluids from a ruptured bowel. This procedure can be performed under local anesthesia without leaving the nursery.

Scientists are also studying potential future treatments, including beneficial bacteria known as probiotics, certain agents that could block the production of nitrous oxide, and even low doses of carbon monoxide.

What else can Necrotizing Enterocolitis be?

The symptoms of necrotizing enterocolitis, a serious intestinal disease, can be rather vague and are shared with a wide range of other conditions. This makes the process of correctly diagnosing it quite challenging. These symptoms, which include feeling sick and vomiting, could be due to a number of conditions:

- Born with certain abnormalities, like pyloric stenosis (a narrowing of the opening from the stomach to the intestine), duodenal atresia (a blockage in part of the intestine), tracheoesophageal fistula (an abnormal connection between the esophagus and the trachea), gastroschisis (where the baby’s intestines develop outside the belly), or malrotation with or without midgut volvulus (a twisted intestine).

- An infection causing illness like gastroenteritis (a stomach bug), urinary tract infection, sepsis (a severe infection), meningitis (an infection of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord), and pneumonia (a lung infection).

- Other issues like intussusception (when one part of the intestine slides into another) or testicular torsion (twisting of the spermatic cord).

Additionally, always important to remember that in some unfortunate cases, child abuse, including injuries to the brain caused on purpose, could cause these symptoms too.

What to expect with Necrotizing Enterocolitis

The outlook for a condition called necrotizing enterocolitis, which is when the tissue in a baby’s intestines gets damaged or dies, depends on how severe the condition is when it’s diagnosed and treated. There’s a pretty large range when it comes to survival rates, at 10% to 50%. However, in severe cases of necrotizing enterocolitis where the disease has caused complete damage to the intestinal wall, leading to holes and serious inflammation, the survival rate is unfortunately nearly 0%.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Staying in the hospital for extended periods and receiving long-term treatment can result in various complications. One such complication is the need for long-term parenteral nutrition, a method of feeding patients via a vein, and this could potentially cause liver failure. Following an operation, the formation of scar tissue may result in the narrowing or blocking of organs or tubes in the body.

Other possible complications are short bowel syndrome, a condition where the body is unable to absorb enough nutrients from the food that you eat because a large part of your small intestine is missing or has been surgically removed. Intestinal failure, where your intestines cannot absorb enough water, vitamins, and other nutrients, may also occur. Nutritional deficiencies and defects in growth and development can also potentially occur as a result of these complications.

Common Complications:

- Extended parenteral nutrition leading to potential liver failure

- Scar tissue formation leading to strictures and blockages

- Short bowel syndrome

- Intestinal failure

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Delayed growth and development

Recovery from Necrotizing Enterocolitis

After a surgical procedure for a severe intestine disease known as necrotizing enterocolitis, babies need to get antibiotics through an IV line and receive special nourishment called total parenteral nutrition, which is an IV based feeding system. This should continue for at least 2 weeks. During this period, regular medical attention should be given to check and manage any imbalances of minerals in their body fluids (electrolyte abnormalities) or conditions of low red blood cells count (anemia). If the baby has difficulty in breathing, they would be given assistance through a machine (ventilatory support).

Preventing Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Infants born with extremely low birth weights that are breastfed typically have a reduced risk of developing a serious intestinal condition known as necrotizing enterocolitis. This condition involves damage and infection to the intestines and is very serious. Therefore, mothers of these small babies should be advised about the many benefits of breastfeeding, particularly how it can help prevent necrotizing enterocolitis.

There are certain conditions before and after birth that can disrupt blood flow to the baby’s intestines, and this has been tied to higher chances of developing necrotizing enterocolitis. For instance, if the mother has conditions that disrupt blood flow to the placenta (the organ supplying oxygen and nutrients to the baby) during pregnancy, like high blood pressure, preeclampsia (a complication characterized by high blood pressure and signs of damage to another organ system), or cocaine use, this may reduce blood flow to the baby’s intestines. In such cases, feeding the baby with caution is sensible to lower the risk. After birth, conditions that decrease the same blood flow and hence increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis include a condition in which a temporary blood vessel called the ductus arteriosus remains open, other heart diseases, or overall low blood pressure and heart-related issues.