What is Cavernous Venous Malformation?

Cerebral cavernous malformations, also known as cavernomas or cavernous hemangiomas, are groups of unusual blood vessels in the brain that lack any brain tissue around them. They usually have minor bleeding and clot formation around them, which leads to a build-up of a certain type of iron deposit (hemosiderin) and scar tissue (gliosis). These abnormal blood vessels don’t have high pressure or fast flow; thus, their chance of bursting is lower than other types of abnormal blood vessels, like arteriovenous malformations. Often, these malformations are found by accident during medical tests, but sometimes they can be discovered when doctors are investigating symptoms like headaches, seizures, specific neurological issues, or symptomatic bleeding.

Mostly, these malformations are located in the upper part of the brain. However, they can also be found in parts like the basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum, and spine. Sometimes, they can be associated with unusual blood vessels present since birth, known as developmental venous anomalies (DVAs).

On average, the yearly rate at which these malformations bleed is reported to be quite low – 0.7%-1.1% for each malformation in patients who have not had a prior bleeding incident. However, this risk almost quadruples to around 4.5% in patients who have previously had a bleeding incident in the brain. The chance of bleeding is believed to decrease about two to three years after such a bleeding event. Factors that determine the risk of bursting include the malformation’s position, the presence of associated DVAs, and the patient’s gender. Lower parts of the brain, deeper locations, younger age, and being female are associated with a greater risk. Unnoticeable familial cases are also believed to have a higher yearly bleeding rate than asymptomatic random cases.

Cavernous malformations can also come up on their own. Over time, they may grow, shrink, or remain the same size.

What Causes Cavernous Venous Malformation?

Cavernomas, or blood vessel abnormalities in the brain, can either be acquired sporadically or inherited through families. Approximately half of the cases are inherited. When a person acquires this condition sporadically, they usually have one cavernoma, whereas people with inherited cavernomas often have multiple.

In families with this condition, it’s usually caused by a dominant gene mutation located either on the 7q, 7p, or 3p chromosomes. These genes interact with specific proteins involved in the development of new blood vessels in brain tissue.

Research found a common gene deletion among Ashkenazi Jews that can result in them having a higher risk of developing this condition.

Furthermore, recent research into cases where there was no inherited genetic mutation found that these cases shared mutations in the same three genes as inherited cases. This suggests that the causes of both inherited and spontaneous cavernomas may be the same at a molecular level.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Cavernous Venous Malformation

Cavernomas are not very common, affecting only about 0.4% to 0.8% of people in general. Despite their rarity, they are the most frequent abnormality found in blood vessels in the brain, making up 10% to 25% of all such conditions. Cavernomas can affect anyone, regardless of gender. They can be found in both adults and kids, but they usually appear when a person is in their 40s. Interestingly, if a person has a family history of cavernomas, it’s more common in people of Hispanic-American descent, with rates as high as 50%.

- Cavernomas affect about 0.4% to 0.8% of people.

- Despite being rare, they make up 10% to 25% of all abnormal blood vessel conditions in the brain.

- They can affect anyone, men and women alike.

- Both adults and kids can get them, with the average age being in the 40s.

- If there’s a family history of cavernomas, it’s most common in Hispanic-Americans, up to a 50% rate.

Signs and Symptoms of Cavernous Venous Malformation

Cavernomas are benign brain tumors that might lead to symptoms such as headaches, seizures, and neurological problems, or they might cause no symptoms at all, in which case they’re usually found during scans for other conditions. In a study, it was found that the most common symptom of cavernomas was seizures, accounting for about 40.6% of cases. Hemorrhage, or bleeding, from the cavernoma happened in around 0.7% to 6.5% of cases, though reports vary. The most common symptoms depended on the tumor’s location: seizures were common if the cavernoma was in the upper part of the brain, while neurological deficits or difficulty in coordination were typical when the cavernoma was in the lower part of the brain. The number of cavernomas discovered incidentally has probably increased over time owing to widespread use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). If a cavernoma is found, a thorough inspection of the patient’s neurological history, medication, any incident of seizures, and family history of vascular malformations is helpful.

- Seizures

- Headaches

- Neurological deficits

- Hemorrhage (in some cases)

- Discovered incidentally (in some cases)

- Thorough review of prior neurological events

- Review of any antithrombotic medications

- Seizure history

- Detailed neurologic exam

- 3-generation family history, especially of vascular malformations

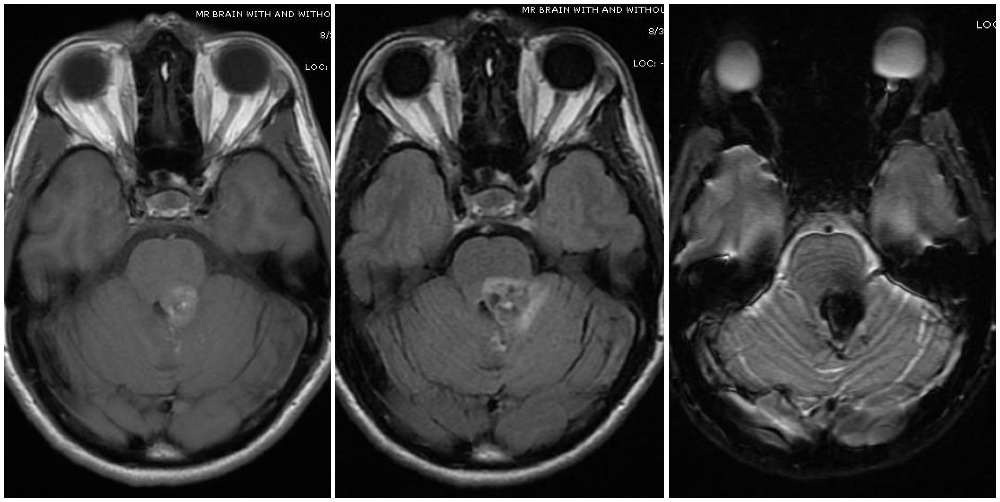

cerebellar peduncle of a patient who presented with right sided facial numbness

and ataxia. Varying signal intensities on T1- and T2-weighted sequences and

detection of blood on susceptibility weighted sequences (left, middle, and right

images, respectively) that are characteristic for a cavernoma are seen. Imaging

findings consistent with a Zabramski type 2 cavernoma with mixed signal

intensities on both type 1 and type 2, giving it the “popcorn appearance”.

Testing for Cavernous Venous Malformation

Cavernomas, or vascular malformations, can be challenging to diagnose due to their slow blood flow and tiny blood vessels. They can be especially hard to detect with cerebral angiography, a technique for examining blood vessels in the brain.

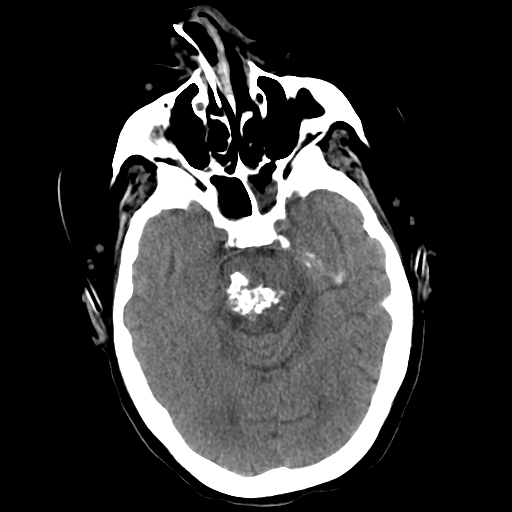

When viewed with a type of scan called computed tomography (CT), cavernomas may appear well-defined and dense. This density is associated with things like clotting, increased blood volume, and the build-up of hemosiderin, a substance produced when blood breaks down. However, CT scans are not very accurate for diagnosing cavernomas and can miss or wrongly diagnose them. Therefore, they’re not the best first choice for diagnosing these disorders.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), on the other hand, is the better option. Special techniques called gradient-echo sequences (T2*/GRE) and susceptibility-weighted imaging sequences (SWI/VenBold) can clearly show hemosiderin and areas of prior bleeding when done at higher intensities. The MRI scans display mixed signals of blood at various stages, along with calcifications (hardened areas) and a surrounding ring of hemosiderin.

Cavernomas can appear differently on MRI and are grouped into four categories. Type I and II lesions show up as bright areas with a core of hemosiderin. Type II lesions, in particular, have a characteristic “popcorn” look with various stages of bleeding enclosed by inflammatory margins. Type III lesions show chronic resolved bleeding within an isointense core. Lastly, Type IV lesions are considered small capillary telangiectasias that are only visible with specific MRI sequences. Types I and II are considered to have a higher risk of bleeding, which may require more aggressive surgical management.

Other techniques like diffusion tensor sequences and functional MRI (fMRI) can be useful for planning surgery by showing white matter tracts and important areas. Recognizing associated developmental venous anomalies is also important; if several cavernomas surround the periphery of a single anomaly, this suggests a single vascular complex consistent with a non-familial occurrence.

New MRI techniques like quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) and dynamic contrast-enhanced quantitative perfusion (DCEQP) can measure the level of iron deposition and blood vessel permeability in cavernomas. These techniques have potential as biomarkers or indicators of disease activity.

Treatment Options for Cavernous Venous Malformation

The three main therapies for managing cerebral cavernomas (blood vessel abnormalities in the brain) are monitoring with periodic imaging, surgically removing the cavernoma, and a technique called stereotactic radiosurgery. When considering the suitable treatment, doctors need to balance the risks of the treatment against the dangers of leaving the cavernoma untreated. Various aspects guide this decision, like the natural tendencies of the cavernoma, its clinical manifestation, location, repeat bleeding events, and other health conditions the patient has. If the cavernoma is small and was discovered incidentally, simply watching over time may be the best course.

Guidelines from the Angioma Alliance in 2017 state that surgery is usually not recommended for cavernomas that don’t cause symptoms. This is particularly true when there are multiple cavernomas or they are located in important or deep areas of the brain. However, if there’s only one non-symptomatic cavernoma located in a non-crucial and reachable area of the brain, surgery could be considered. Advantages of surgery can include preventing bleeding, reducing follow-up times, lessening anxiety, and facilitating treatments that might be needed later.

The same guidelines suggest considering early surgery if a patient’s epilepsy is caused by the cavernoma, as this could prevent a worsening of seizure activity and increase the chances of seizure-free life. The risks related to the surgery should be weighed against the length of time the patient would be living with the cavernoma, which might be around 2 years for symptomatic and surgically accessible cavernomas, and 5 to 10 years for symptomatic and deeply located cavernomas. Surgery on cavernomas located in the brainstem is typically not recommended due to high risk of complications, but may be considered if the patient has suffered from a second bleeding episode.

Before surgery, doctors may prescribe steroids to reduce brain swelling and facilitate the surgery. The doctor will aim to remove the entire cavernoma to prevent future bleeding. If the surgery is for seizures, it is also best to remove the surrounding brain tissue stained with blood and scar tissue, when possible. A follow-up MRI within 72 hours after the operation is recommended to confirm that the whole cavernoma has been removed.

Stereotactic radiosurgery is another treatment option that can be considered as an alternative to traditional surgery, although its effectiveness in reducing re-bleeding is still debated. Even though traditional surgery remains the standard treatment, radiosurgery can be an option for symptomatic cavernomas that pose a high surgical risk. It’s generally not suggested for symptom-free cavernomas, or those that can be easily reached by surgery, due to risk of new cavernoma formation.

Genetic testing is advised for patients newly diagnosed with a cerebral cavernoma, especially if there’s no history of brain radiations, no family history, or multiple cavernomas. If a gene mutation linked to cavernomas is found, genetic counselling should be offered to the patient and their family. Family members of patients with a family record of cavernoma should also be offered a screening MRI and genetic counselling.

Medical treatments, currently being tested, including the ROCK inhibitor, statins, vitamin D, and B-cell depletion, have shown promise in reducing bleeding in cavernomas.

What else can Cavernous Venous Malformation be?

When a doctor tries to determine if you have a certain kind of brain blood vessel disorder known as cerebral cavernous malformations, they may also consider similar conditions such as:

- Arteriovenous malformations

- Vein abnormalities known as venous angiomas

- Abnormal clusters of blood vessels called capillary telangiectasias

- Irregular connections between blood vessels known as dural arteriovenous fistulas

- An inflated, weak area in a blood vessel wall, or aneurysm

- Vein of Galen malformations, a rare blood vessel disorder in the brain

An MRI is usually the best way to detect cerebral cavernous malformations because it can clearly show the abnormalities in the brain. However, in some situations, such as when sudden bleeding has happened in the brain, other tests like angiography (x-ray of blood vessels) may be useful to rule out other possible brain blood vessel disorders.

What to expect with Cavernous Venous Malformation

The outlook of a condition largely depends on where the bleeding is located and the severity of neurological issues someone has.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Cavernous Venous Malformation

The main problems that can occur with cavernomas are internal brain bleeding, neurological damage, seizures, and in rare cases, they can also pose a risk to life.

Common Issues:

- Internal brain bleeding

- Neurological damage

- Seizures

- Rare risk to life

Preventing Cavernous Venous Malformation

For people with cavernomas, it might be necessary (though not scientifically proven) to limit certain activities. This may include mountain climbing above 10,000 feet, smoking, water activities, and contact sports. The majority of research indicates that if these people also have other conditions that require them, it’s generally safe to take medications that stop blood clots, which are called antiplatelet drugs.