What is Viral Hepatitis?

Hepatitis is a condition characterized by the inflammation of the liver. Several factors can cause this, like heavy drinking, certain diseases, drugs, or toxins. However, the most common cause is usually a viral infection, widely known as “viral hepatitis”. In the United States, hepatitis A, B, and C are the most common types, while hepatitis D and E are less common.

The seriousness of hepatitis can vary based on what causes it. In some cases, it can be mild and goes away on its own, while in severe cases, it could require a liver transplant. Hepatitis can also be categorized as “acute” or “chronic” based on how long the liver remains inflamed. If the inflammation lasts less than 6 months, it’s considered “acute”. If it lasts more than 6 months, it’s classified as “chronic”.

While acute hepatitis usually resolves on its own, it can sometimes lead to severe liver damage based on what caused it. On the other hand, chronic hepatitis can eventually lead to serious conditions like liver scarring, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and conditions related to high blood pressure in the liver. These outcomes can significantly impact a person’s health and can be life-threatening.

What Causes Viral Hepatitis?

Viral hepatitis is usually caused by five different viruses, hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. Other types, like hepatitis G virus, and those caused by viruses such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus are rare and less clearly linked with causing hepatitis.

In the United States, the majority of hepatitis cases are due to hepatitis A, B, and C, with hepatitis C being the most common reason for long-lasting, or chronic, hepatitis.

The type A hepatitis virus, known scientifically as an RNA virus, is most often found in fecal matter and can be easily spread in places with poor sanitation or through contaminated food and water. Travel to countries with these conditions is the most common risk for contracting hepatitis A in the United States.

Hepatitis B is another type of virus. It can be found in several different bodily fluids like blood, semen, vaginal mucus, saliva, and tears, but not in stool, urine, or sweat. It can spread through sharing needles, sexual contact, or contact with infected bodily fluids, meaning people like drug users, people with multiple sexual partners, healthcare workers, or people born in areas where the disease is common, are at higher risk.

The type B virus can also pass from mother to child during childbirth, especially if the mother has a lot of the virus in her blood. Infected infants are at a high risk of developing a lasting infection.

Hepatitis C is much the same, commonly spreading through shared needles among drug users, and less commonly through sex or from mother to child during childbirth. It’s difficult to create a vaccine due to the many different strains of the hepatitis C virus.

Hepatitis D also spreads like B and C but is unique in using the presence of the hepatitis B virus to replicate in the body. It doesn’t often pass from mother to child.

Hepatitis E generally spreads like type A – through contaminated water or food in areas with poor sanitation.

Finally, there’s the hepatitis G which can be found in people with chronic hepatitis B or C infections. However, it’s not definitively linked to causing hepatitis on its own. Its primary mode of transmission is through infected blood and blood products, while it can also spread via sexual contact and from mother to child.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is a significant health concern across the world, infecting millions of people each year and often leading to severe health complications and even death. Issues can include liver damage such as fibrosis and cirrhosis, liver cancer, and signs of portal hypertension. The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 1.3 million people died from hepatitis in 2015 and that a third of all people worldwide have been infected with either the B or C form of the virus. The B and C forms, in particular, are responsible for most of the 1.4 million deaths each year from viral hepatitis. Current global infection rates suggest that 2 billion people carry the B virus, 185 million carry the C virus, and 20 million carry the E virus.

- Hepatitis A: In the US, around 24,900 new infections with this virus occur each year. It is less common in areas with safe drinking water and sanitation. Areas with less socioeconomic advantage have higher infection rates. It affects most children in highly affected regions, with the vast majority of the population having been infected. In these areas, early infection often leads to lifelong immunity.

- Hepatitis B: Around a third of all people globally have been infected with this type, and about 5% remain carriers. Of these, about 25% develop serious liver complications, leading to around 780,000 deaths every year. In the US in 2018, there were approximately 22,600 new cases, and it’s estimated that 862,000 people currently have a chronic infection.

- Hepatitis C: This type is the most common cause of hepatitis spread through blood around the world. It affects between 0.5% and 2% of the global population, particularly affecting people who use drugs intravenously and hemophiliacs. About 71 million people worldwide have a chronic infection, leading to nearly 400,000 deaths every year. In the US in 2018, there were about 50,300 new cases and it’s estimated that 2.4 million people have a chronic infection.

- Hepatitis D: This type only infects people who already have Hepatitis B. Accurate data is not available in the US, but it’s estimated it affects up to 8% of acute B cases and 5% of chronic B cases, affecting about 18 million people globally.

- Hepatitis E: This type affects about 20 million people worldwide, often in developing countries with limited access to clean water and sanitation; it caused about 44,000 deaths.

- Human Pegivirus: Its global infection rate is about 3%, and up to 4% of blood donors carry the virus. About 25% of people globally carry an antibody to the virus. It’s not usually screened for in blood donations due to lack of evidence for causing disease. Coinfection is common, but doesn’t seem to worsen the severity of B or C. Rarely, it can be passed from mother to newborn.

Signs and Symptoms of Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis can cause different symptoms depending on which hepatitis virus a person has. Some people don’t experience any symptoms, while others may have mild ones. A small number of individuals may develop sudden and severe liver failure. Most people with viral hepatitis experience four stages, with the symptoms and physical signs varying at each stage. These stages are:

- Phase 1 (Incubation/Viral Replication Phase): People typically don’t have symptoms at this stage, although tests can show signs of hepatitis.

- Phase 2 (Prodromal Phase): People might have symptoms like loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, general discomfort, itching, hives, joint pain, and fatigue. These symptoms are often mistaken for a stomach virus or other viral infections.

- Phase 3 (Icteric Phase): People often produce dark urine and light stools, and may develop yellowing of the skin and eyes known as jaundice. Some have pain in the upper right part of the abdomen due to liver enlargement. Tests will show elevated liver enzymes.

- Phase 4 (Convalescent Phase): Symptoms start to lessen at this stage, and liver enzymes return to normal levels.

Different types of hepatitis may present differently:

- Hepatitis A: Symptoms are similar to a stomach virus or a respiratory virus, and include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, fever, jaundice, loss of appetite, and dark urine. Symptoms usually start after an incubation period of about 4 weeks.

- Hepatitis B: Symptoms include loss of appetite, general discomfort, and fatigue. Some people may have pain in the upper right part of the abdomen, fever, joint pain, or a rash. Later, people may develop jaundice, liver pain, dark urine, and light stools. Some see their symptoms improve quickly, while other people may experience a prolonged illness.

- Hepatitis C: Symptoms are similar to Hepatitis B and include loss of appetite, general discomfort, and fatigue. However, 80% of patients don’t have symptoms and don’t develop jaundice.

- Hepatitis D: Most people with both Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D infections have an infection that clears up on its own. However, those who have chronic Hepatitis B and become infected with Hepatitis D often have more severe hepatitis. Most of these people will develop a chronic Hepatitis D infection.

- Hepatitis E: Patients with this type of hepatitis tend to have a self-limiting infection that’s similar to Hepatitis A. However, pregnant women with Hepatitis E have a higher risk of death.

- Human Pegivirus: People with this type of hepatitis can have a mild infection without jaundice, but most do not have symptoms.

Physical signs can vary depending on when the person comes in for examination. They may have a mild fever, signs of dehydration such as dry mouth, increased heartbeat, and slow blood refill in the nails. During the icteric phase, people can have jaundiced skin or eyes and sometimes hives. The liver may be tender to the touch. In advanced liver failure, there may be signs of fluid buildup in the abdomen (ascites), foot swelling (edema), and malnutrition.

Testing for Viral Hepatitis

If your doctor suspects you might have viral hepatitis, they may first order a liver function test. In severe cases, this test may reveal higher total bilirubin levels. Usually, another substance in your liver called alkaline phosphatase (ALP) stays within the normal range. But if it’s significantly high, that could be a sign of a blocked bile duct.

Other symptoms of advanced liver disease may also show up in your bloodwork. These include increased prothrombin time (PT) and international normalized ratio (INR), which indicate your blood isn’t clotting as quickly as it should. White blood cells and platelets might be low, and you may have anemia. Higher creatinine could mean the liver injury is impacting kidney function. If you’re experiencing confusion or other changes in mental status, your doctor might order an ammonia level test, as high ammonia can signal hepatic encephalopathy, a condition involving brain damage due to liver disease.

Furthermore, there are specific tests to identify various types of viral hepatitis.

For Hepatitis A, a presence of immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies signals an acute infection. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies suggest a past infection, which can be recent or decades old, providing lifelong immunity against the virus.

In diagnosing acute Hepatitis B, the first marker to appear in the blood is HBsAg. It shows the individual has a Hepatitis B infection but does not differentiate between acute or chronic. If HBsAg remains in the blood for more than six months, this suggests a chronic infection.

For Hepatitis B, the first antibody to appear is the IgM antibody. The hernia B e antigen (HBeAg) appears early in the infection, indicating viral replication.

In diagnosing chronic Hepatitis B, a positive HBsAg indicates a chronic infection. These individuals can be inactive carriers or have active chronic hepatitis.

Diagnosis of Hepatitis C usually involves a test for antibodies to the virus (anti-HCV). The presence of anti-HCV generally signifies a past or present infection. The Hepatitis C RNA test confirms the infection and can also provide information on viral load and genotype, which can guide treatment.

In cases of Hepatitis D, HDV infection is diagnosed by checking for IgM and IgG antibodies. A HDV RNA test can also be done, but is not routine.

For Hepatitis E, the infection is diagnosed by checking for IgM and IgG antibodies, and by checking the presence of HEV RNA in the serum and stool of infected patients.

Finally, Human Pegivirus is usually identified by checking the hepatitis G RNA PCR. Following the clearance of the virus, the antibody appears, and patients fully recover. Some patients, however, may go on to develop liver fibrosis.

In general, these specific tests help doctors identify the cause of the liver condition, enabling appropriate treatments to be administered.

Treatment Options for Viral Hepatitis

When managing acute viral hepatitis, the care is mainly supportive and patients can usually be monitored at home. The infection generally clears up on its own over time. It’s crucial though to prevent the disease from spreading to those close to the patient.

In some cases where the person is very nauseous or vomiting a lot, or where there’s an increased risk of dehydration, hospital admission for intravenous hydration may be needed. Substances harmful to the liver, like alcohol, and certain medications processed by the liver, such as acetaminophen, must be used cautiously. Serious complications such as liver abscess or acute liver failure need hospital care and timely management. If the case is unusually severe or long-lasting, a specialist in diseases of the stomach and liver (gastroenterologist or hepatologist) should be involved.

Specific types of Hepatitis (A, B, C, D, E) have different treatments:

Hepatitis A: Supportive care is the mainstay of treatment. Antiviral therapies aren’t available for HAV infection. Severely ill patients needing close attention should be hospitalized.

Hepatitis B: Acute HBV infection treatment is similar to HAV, but medications can be considered for severe infections or in special cases where there is a co-infection with other viruses. Traditional antiviral medications can effectively manage chronic HBV infection which mainly aims to stop the virus from multiplying. Yet, these therapies should be chosen considering patient preferences, cost, risk of drug resistance and others.

Hepatitis C: The key goal of treating chronic HCV infection is to completely eliminate the virus from the body. The choice of treatment depends on whether the patient has had treatments before, their liver health, and if there are any complications. The latest generation of antiviral drugs have made treatment more accessible and effective.

Hepatitis D: Patients with HDV and HBV co-infection are treated with certain antivirals, which are so far the only effective treatment. However, more research is needed in this area.

Hepatitis E: Just like HAV, the treatment for acute HEV infection is mainly supportive. However, immunocompromised patients and organ transplant recipients can take an antiviral therapy.

Human Pegivirus: As of now, there’s no specific treatment for this type of Hepatitis. When liver cirrhosis develops, treatment methods used for cirrhosis caused by other conditions are applied.

What else can Viral Hepatitis be?

Viral hepatitis can present with various symptoms that are not very unique, so it can be confused with other liver conditions and ailments that cause similar symptoms. Patients with acute and chronic viral hepatitis infections can experience general discomfort, tiredness, a mild fever, a loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. A physical exam may not show anything remarkable, or it may reveal tenderness in the upper right section of the abdomen along with an enlarged liver, a specific type of rash, and possible signs of dehydration. In more advanced stages of liver disease from chronic viral hepatitis, patients may display symptoms such as vomiting blood, fluid accumulation in the abdomen, swelling of the feet or legs, or confusion and disorientation related to liver disease.

There are many conditions related to the liver and otherwise, which can show similar symptoms to viral hepatitis. These include drug-induced hepatitis, gastrointestinal infections caused by viruses or bacteria, acute gallbladder inflammation, issues with gallstones, a genetic condition that causes excessive iron build-up in the body called hereditary hemochromatosis, and cancers like pancreatic cancer, lymphoma, liver cancer, and stomach ulcers. Severe heart failure can also result in swelling of the feet, fluid build-up in the abdomen, and an enlarged liver due to liver congestion.

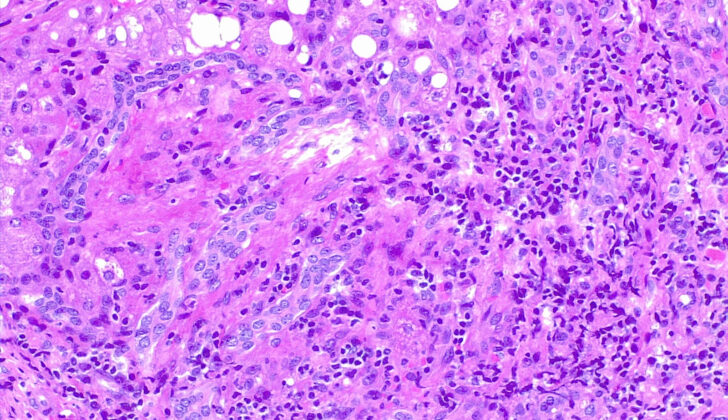

Hereditary hemochromatosis is a genetic condition that distorts the body’s ability to regulate iron, leading to excessive iron deposits in different body organs, including the liver. This is typically diagnosed by checking serum iron, serum ferritin, and serum transferrin levels. Sometimes, a biopsy of the liver may be necessary to check for the extent of fibrosis and distinguish it from other liver conditions, such as viral or autoimmune hepatitis. Patients may experience joint pain, and some may report pain in the knuckles of their first two fingers, a symptom particularly associated with hereditary hemochromatosis.

Patients suffering from drug-induced hepatitis and inherited liver diseases can show similar symptoms to viral hepatitis. Thus, a thorough medical history is crucial in these cases. Drug-induced liver injuries are increasingly common, with over a thousand identified drugs linked to such injuries and ongoing research to discover more. These patients may display no symptoms, with only unusual lab test results indicating liver inflammation, or they may have acute or chronic hepatitis or even acute liver failure.

To differentiate between these conditions, it’s important to take a detailed medical history and conduct laboratory tests and, if necessary, a liver biopsy. The conditions that could potentially cause confusion in the diagnosis of viral hepatitis include:

- Liver abscess

- Liver cancer

- Pancreatic cancer

- Drug-induced hepatitis

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Acute inflammation of the bile duct

- Acute inflammation of the gallbladder and gallstone pain

- Pancreatitis

- Gastrointestinal infection

- Gallstones

- Stomach ulcers

- Small bowel obstruction

What to expect with Viral Hepatitis

The outlook of viral hepatitis varies depending on the specific virus causing the infection.

Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) infection is typically mild and clears up on its own. People who get infected with HAV become immune to future infections from the same virus. Death from HAV is unlikely and complications like relapse, jaundice, and serious liver failure are uncommon. However, those with weakened immune systems, elderly individuals, and young children are at a higher risk than healthy adults.

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) infection can lead to long-term liver inflammation, liver scarring (cirrhosis), and liver cancer. Severe liver failure occurs in about 0.5% to 1% of people infected with HBV. If this happens, there is about an 80% chance of death. Chronic HBV causes around 650,000 global deaths every year.

Half to over half of those infected with Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) will develop a long-term infection. This puts them at risk of developing cirrhosis and liver cancer. Chronic HCV used to be a major reason for liver transplants. Deaths from HCV in the US increased each year until 2013. After highly effective anti-HCV medication became available in 2013 and 2014, both death rates and the need for liver transplants dramatically decreased. However, death rates remain high in developing countries.

Those with chronic HBV who later get infected with Hepatitis Delta Virus (HDV) tend to also develop chronic HDV infection, which generally leads to more serious liver disease than having chronic HBV alone. Many of these patients will progress to end-stage liver disease and cirrhosis.

Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) is similar to HAV in that it is typically a mild illness that clears up on its own. However, pregnant patients may have a mortality rate up to 15% to 25%. The exact reason why it causes such a severe infection in pregnant women, resulting in high mortality rates, is not clear.

Most people with the human pegivirus-1 have no symptoms in the early stages of infection and have normal liver enzyme levels. Severe liver failure and long-lasting infections are rare. Although this virus commonly coexists with HBV and HCV, it does not make the disease worse.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis can result in numerous complications such as chronic active hepatitis, acute or subacute liver cell death, liver failure, cirrhosis, hepatic encephalopathy (brain dysfunction caused by liver disease), and liver cancer particularly in patients with Hepatitis B or C. Antiviral therapy can be used to treat these complications in some cases.

Patients with chronic Hepatitis B are at risk for liver cancer, even without cirrhosis. Hepatitis B-related liver cancer accounts for 45% of primary liver cancer cases worldwide. Roughly 1% of patients can also develop severe liver failure, with a mortality rate of about 80%.

Over half of Hepatitis C patients develop chronic infections, with about one-fifth of these patients developing cirrhosis, and some eventually getting liver cancer. Complications of cirrhosis can include brain dysfunction due to liver disease, portal hypertension (high blood pressure in the vein to the liver), fluid in the abdomen, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (infection in the abdomen), bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome (kidney failure due to advanced liver disease), and may lead to liver cancer.

Treating liver-related complications is largely linked to managing cirrhosis and is best done by liver disease specialists. Liver transplant can be a cure for cirrhosis complications in suitable patients.

Patients who develop brain dysfunction from liver disease are primarily treated with oral lactulose. When lactulose isn’t enough, rifaximin, an antibiotic, is FDA-approved to be added to the therapy. Giving somatostatin or octreotide and preventive antibiotics is the standard treatment for active gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients with bleeding varices (swollen blood vessels) require immediate restoration of circulatory function, securing airway, endoscopy for examining the digestive tract, sclerotherapy or banding for restraining the varices. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement is a rescue therapy for variceal bleeding that is not controlled with endoscopy.

Ascites (fluid in the abdomen) is initially managed by limiting dietary sodium intake to 2000 mg per day and treatment with oral diuretic drugs. Paracentesis, a procedure to remove fluid from the abdomen, is reserved for those uncontrolled by initial measures or who are severely symptomatic and need immediate relief. TIPS can also be considered for ascites otherwise challenging to control. If ascites are complicated by a spontaneous bacterial infection, known as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, treatment generally involves intravenous antibiotics and subsequent antibiotic maintenance is required to prevent further infection.

All patients who develop liver cancer as a result of viral hepatitis may be eligible for therapies directed at the liver tumor, such as radiofrequency ablation, chemoembolization, systemic chemotherapy, or surgical resection in carefully selected patients.

Patients with chronic Hepatitis C infection may also develop complications outside of the liver, including clotting disorders and cryoglobulinemia, which can lead to rashes, inflammation of the blood vessels, and kidney inflammation secondary to the deposition of immune complexes in the small vessels. Other associated disorders include non-Hodgkin lymphoma, focal lymphocytic sialadenitis, autoimmune thyroiditis, porphyria cutanea tarda, and lichen planus. Correction of severe clotting disorders may be necessary in the setting of active bleeding or the need for invasive procedures such as placement of a TIPS or other surgeries.

Preventing Viral Hepatitis

Educating patients is key in preventing and controlling viral hepatitis. People with long-term viral hepatitis need to understand how this disease can spread, plus they’ll need regular check-ups to determine if they need treatment. If the disease gets worse, particularly if there’s evidence of an issue called cirrhosis with or without complications, a specialist, such as a gastroenterologist or a hepatologist, should be consulted quickly.

It’s also important to advise patients not to share personal items like toothbrushes, razors, or needles, which can lead to blood exposure and disease transmission. They should consume fruits and vegetables only after they’re cooked, washed and peeled. If travelling to areas where the disease is commonly found, they should avoid drinking untreated water and eating raw shellfish or seafood. Another recommendation is to avoid things that can be harmful to the liver, like alcohol. The common pain reliever, acetaminophen, which is processed in the liver, should be used carefully and avoided if there is severe liver damage.

For those with Hepatitis A, they should not prepare food for others until they’re no longer spreading the virus. All pregnant women should be checked for HBV infection and HIV infection. If a woman with chronic HBV infection is pregnant, the way the infection is treated will depend on the amount of the virus in her body and her HIV status. Newborns born to mothers with chronic HBV infection should receive treatment and vaccination according to standard protocol to prevent the spread of the virus.

Healthcare workers should have strict infection control practices. Workers at risk of viral hepatitis infection should be vaccinated against HAV and HBV. If there’s a risk of HCV infection, suitable health education, testing and treatment, if needed, should be provided. Health professionals should be trained on how to identify people at risk for viral hepatitis and offer testing and treatment if an infection is detected. Also, all adults aged 18 and older in the US should be screened for HBV and HCV.

Vaccinations are available for some types of hepatitis and are much easier way to prevent the disease than to treat it.

For Hepatitis A, people working with adults at high risk for the infection and those travelling to affected areas should receive a vaccine before the risk of exposure increases. Other people who should be offered the vaccine include those with a condition known as hemophilia, drug users, men who have sex with men, patients with chronic liver disease, those awaiting or who have received a liver transplant, and those who work with primates in laboratories. Inactivated HAV vaccine can be injected in the muscle and a booster vaccine is recommended after six months.

For Hepatitis B, vaccinations should be included in routine immunizations for infants, and adults at high risk of infection. This includes patients on dialysis, healthcare workers who may be exposed to blood and body fluids, people with sexual partners with HBV infection, people having casual sex, those being checked or treated for sexually transmitted diseases, men who have sex with men, shared needle users, those living in the same household as someone with HBV infection, residents and staff of facilities for the developmentally disabled, and correctional facilities. Patients with chronic liver disease should also be offered the HBV vaccine. Infants born to mothers who have HBV infection should be vaccinated within 12 hours of birth.

Currently, there are no vaccines against Hepatitis C and the use of immunity-providing blood proteins, known as immunoglobulins, hasn’t been effective in preventing transmission. Thus, it’s important to use infection control practices to prevent contamination and transmission of this virus.

For Hepatitis D, which only occurs alongside HBV infection, transmission can be prevented by vaccinating patients against HBV. However, there is currently no way of preventing HDV disease in patients with chronic HBV infection.

There is currently no vaccine available for Hepatitis E or Hepatitis G. Therefore, certain groups who are at high risk, like those undergoing transplant, people frequently receiving transfusions, injection drug users, patients on dialysis, and men who have sex with men, have to take extra precautions.