What is Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack)?

Anteroseptal myocardial infarction (ASMI) is a term that was traditionally used based on certain heart waves or changes spotted on an EKG heart test. Specifically, these EKG findings in leads V1-V2 identify an occurrence of ASMI. Past investigations of patients who had a heart attack with these particular EKG changes mostly found damage in the basal anterior septum part of the heart. This was the common belief until recent research using modern heart imaging techniques revealed that it’s usually not the basal anterior septum involved, but rather the apical and anteroapical parts of the heart muscle.

This term ‘anteroseptal’ originated from post-death examination data. Several efforts have been made to map out the different segments of heart muscle using various imaging tools. For instance, an echocardiogram divides the heart into 16 segments while a specific type of imaging test known as SPECT-MPI uses a 17-segment model. This 17-segment model, which is agreed upon more according to autopsy studies, looks at the length and circumference of the heart and divides it into a total of 17 different segments.

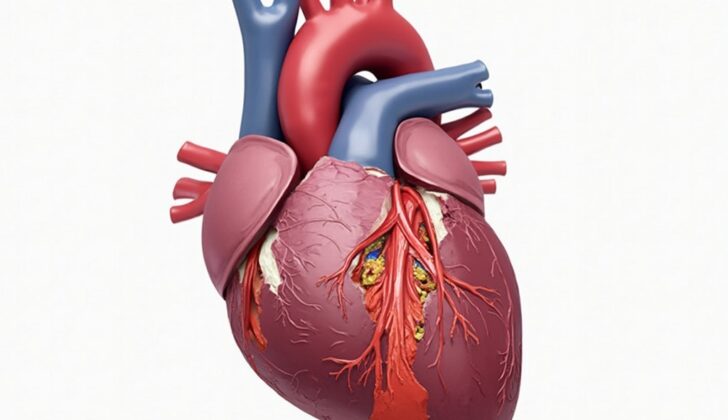

The left ventricle of the heart is divided into 17 segments which includes parts like the Basal anterior, Basal anteroseptal, Mid anterior, Mid anteroseptal, Apical anterior, and Apical septal to name a few. It’s worth noting that heart attacks affecting just the anteroseptal area, which includes basal anteroseptal, mid anteroseptal, and apical septal segments, are fairly rare.

The blood vessels most commonly supplying these segments are the left anterior descending artery and its branches. However, there can sometimes be variations in the heart’s blood vessel anatomy.

What Causes Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack)?

The cause of an anteroseptal myocardial infarction, also known as a heart attack, is similar to other types of heart attacks. However, the problem usually involves the left anterior descending artery or one of its branches.

There are two main ways this can happen:

1. Obstructive: This is when something like a clot or embolus blocks the flow of blood in the coronary arteries.

2. Non-obstructive: This is also referred to as a heart attack with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA). This could be due to things like plaque buildup on the artery walls, a spasm in the coronary artery, an artery buried within the heart muscle (known as myocardial bridging), or a tear in the coronary artery.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack)

The impact of anteroseptal myocardial infarction (heart attacks that affect the front and middle part of the heart muscle) specifically isn’t widely studied. However, heart attacks overall are a major public health concern because risk factors for heart disease are increasingly common. Studies indicate that non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarctions (a type of heart attack) are becoming more frequent. On the other hand, the occurrence and hospital death rates for ST segment elevation myocardial infarctions (a different type of heart attack usually more serious) are decreasing.

Signs and Symptoms of Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack)

An anteroseptal myocardial infarction (MI) is a type of heart attack. The symptoms are similar to other types of heart attacks and can include:

- Chest discomfort, often felt as tightness in the area beneath the breastbone, which may radiate to the jaw, neck, left shoulder, or inner aspect of the left arm

- Shortness of breath

- Feeling sick (nausea)

- Sweating heavily (diaphoresis)

- Less common symptoms: upset stomach, severe tiredness, fainting, or shortness of breath from mild exertion.

Some people, like women, older people, or people with diabetes, may not have typical symptoms. Instead, they may feel tired for no clear reason, or may not feel any symptoms at all.

If an individual has previously had a heart attack or heart disease, any new chest discomfort should be evaluated carefully. Things like the location, timing, severity, and what makes the pain better or worse, can be important information for the doctor.

It’s also important for these people, and for those at risk of heart disease, to be alert to new heart-related symptoms. This requires a careful medical evaluation.

During a physical exam, the doctor will note the heartbeat and rhythm, and compare the blood pressure in both arms. Listening to the heart can further tell if there are additional abnormalities to be concerned about. The doctor will also inspect and touch certain areas of the body to gather additional clues about the person’s health.

- Observation: The doctor will look for signs of a visible heartbeat on the chest, swollen veins on the neck, and swelling in the lower parts of the body.

- Touch: The doctor will feel for an irregular heartbeat, and will compare the strength and rhythm of the pulse in each arm.

- Listening: The doctor will listen to the heart sounds, which can help identify if there’s any abnormal sounds, murmurs, or rhythms. A new murmur or a change in the heart’s rhythm might suggest an issue with the heart’s valves. A sound called a rub might mean there’s inflammation around the heart or lungs.

However, these signs are not exclusive to heart attacks and can also be seen in other conditions. Therefore, any of these signs should prompt further evaluation by a doctor.

Testing for Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack)

If a doctor thinks a patient might be having a heart attack, they should perform an electrocardiogram (EKG) within the first 10 minutes. An EKG monitors the heart’s electrical activity. Changes on the EKG, including ST depression, transient ST-elevation, new T-wave inversions, or even Q-waves, could indicate a type of heart attack known as the acute coronary syndrome.

An anteroseptal heart attack is usually spotted on the EKG due to specific changes in the V1-V3 leads. Over time, Q waves may also develop in these leads, indicating significant damage to the heart muscle. A significant Q-wave is one with a duration of more than 0.03 sec or the height of the Q wave is more than 25% of the height of the following R wave. Also, new ST-segment elevations at the J-point in two adjacent leads are valuable indicators.

If your doctor suspects a heart attack, they might also do a blood test to check for cardiac troponins. If there are higher than normal levels of these proteins in your blood, it could suggest heart muscle damage. High sensitivity cardiac troponin tests can usually spot a heart attack within a few hours of your first symptoms. Once elevated, they may remain high for quite a few days or even longer, up to 2 weeks if the heart attack was severe. A negative troponin value at first hospital visit, means there is a less than 5% chance of a heart attack, making it very helpful for quickly ruling out a heart attack.

Other tests that might be done alongside these include a chest X-ray, to rule out other potential causes of chest pain. A CT scan of the chest with contrast can check for other conditions, like a blood clot in the lungs or a tear in the aorta wall. Finally, point of care ultrasound (POCUS) of the heart can be used to check for any new abnormalities in the left ventricle muscles’ movements. The benefit of using POCUS is that it may show problems earlier in the disease process compared to EKG changes or raised troponin levels.

Treatment Options for Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack)

Treating Acute ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (ASMI), a type of heart attack, is the same as handling any other heart attack. The aim is to relieve pain, prevent the disease from progressing and avoid death. This is achieved through early diagnosis, pain relief, using anti-blood clotting drugs and restoring blood flow. In ASMI, quick restoration of blood flow is crucial to prevent tissue death and life-threatening heart rhythms, and to improve long-term health outcomes.

For ASMI patients who have a shortage of oxygen (oxygen saturation below 90%), difficulty breathing, or signs of respiratory distress, supplemental oxygen is given. For ongoing chest pain, treatment can include nitroglycerin tablets under the tongue every five minutes for up to 15 minutes total. If the pain persists, intravenous nitroglycerin or morphine may be needed.

Oral beta-blocker therapy will be given as soon as possible to most patients, provided they do not have conditions that would make these drugs harmful. For patients who can’t take beta-blockers, a type of medicine called a non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, such as diltiazem, may be an option. High-intensity cholesterol-lowering drugs called statins are given to all patients.

For severe, ongoing chest pain, intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation therapy may be used while waiting for invasive procedures to be carried out. Patients with certain conditions like poor heart function, diabetes, hypertension, or stable kidney disease should start on ACE inhibitors, which lower blood pressure. For patients who can’t tolerate these, blockers of hormones related to blood pressure and fluid balance (aldosterone receptor blockers) can be given instead.

For ASMI patients who have a decreased heart function, adding aldosterone blockers to ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers may improve long-term survival.

Patients suffering from an acute ASMI should quickly get treatment to prevent blood clotting. Aspirin is given as soon as possible to all patients suffering from a heart attack, then continued indefinitely. A P2Y inhibitor, a type of antiplatelet drug, is then given in addition to aspirin for up to a year to all patients after the heart attack.

Regardless of the treatment approach, anticoagulation or the prevention of blood clotting is endorsed for all patients. For this purpose, patients can be given different varieties of medications-like enoxaparin, heparin, fondaparinux, or bivalirudin. For those who have a history of heparin-induced low platelet count, argatroban, a drug that targets clotting proteins, can be used, including those requiring a procedure to unblock blood vessels (PCI).

In the end, restoring blood flow to the heart (revascularization) is the primary goal.

Some patients might need an immediate invasive strategy (a coronary angiography with the intent of performing a procedure to restore blocked vessels within 24 hours). Particularly, patients with constant chest pain, or electrical or hemodynamic instability, or at increased risk for hard clinical events

A delayed invasive approach (within 24 to 72 hours) may be reasonable for patients with low to intermediate clinical risk. The ischemia-guided approach is used to avoid the routine use of early invasive procedures. It is reasonable for low-risk patients.

After surviving a heart attack, the goal is to return the patient to routine activities by focusing on a healthy lifestyle and managing risk factors. Long-term medical treatment is crucial, especially for patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) under 40%. This treatment is based on the benefits of antiplatelets, beta-blockers, statins, and ACE inhibitors from previous studies. Major risk factors like smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol levels, obesity, and lack of physical activity should be treated. Post-discharge, patients should also participate in a cardiac rehabilitation program.

To sum it up, the following steps are crucial in ASMI management: early diagnosis, relieving pain with nitroglycerin, ensuring stable oxygen circulation, restoring blood flow, prevention of re-thrombosis with aspirin and P2Y12-inhibitors, preventing dangerous heart arrhythmias with beta-blockers, and improving long-term survival with statins, aspirin, clopidogrel, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, revascularization, cardiac rehabilitation, and lifestyle changes.

What else can Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack) be?

When trying to diagnose anteroseptal myocardial infarction (a specific type of heart attack), doctors need to consider several other conditions that can cause similar symptoms. These are all part of what is known as the “acute coronary syndrome,” and might include:

- Pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lungs)

- Pericarditis (inflammation of the sac around the heart)

- Aortic dissection (a tear in the large blood vessel branching off the heart)

- Acid peptic disease (ulcers or inflammation in the digestive system)

- Pleuritic chest pain, which can result from lung infection or infarction (death of tissue)

- Musculoskeletal pain, such as in the ribs or due to costochondritis (inflammation of rib cartilage)

What to expect with Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack)

The long-term outlook for individuals who have suffered an anteroseptal myocardial infection (a particular type of heart attack) hasn’t been separately researched yet. In general, people who survive a heart attack face an increased risk of future heart problems, including a higher risk of mortality.

However, the specific outlook for each person can vary greatly and depends on whether or not they have other risk factors. The use of prevention measures can also have a significant effect. Both short-term and long-term death rates after a heart attack have decreased considerably over the past few decades. This is largely due to improvements in medical care, such as more widespread use of techniques to restore blood flow to the heart, and the use of various medications for both primary and secondary prevention.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack)

Complications from an anteroseptal myocardial infarction, or a heart attack in the front part of the heart’s wall, are similar to the ones that can happen after any heart attack. These include:

- Myocardial Dysfunction – poor functioning of the heart muscle.

- Heart Failure – when the heart can’t pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs.

- Mechanical Complications which can be:

- Septal Rupture: this refers to a tear in the wall between the left and right side of the heart. It’s a rare complication. However, when it involves anteroseptal MI involving LAD lesion, immediate recognition and surgical repair become necessary.

- Papillary Muscle Rupture and Free Wall Rupture: these are also rare and generally seen in patients with disease in multiple blood vessels.

- Conduction Abnormalities – these are problems related to the electrical impulses that direct the heart to pump. One study found that a particular type of these abnormalities, called right bundle branch block, was the most common in anteroseptal MI. It even progressed to a complete AV block, a severe heart rhythm problem, in a third of the patients.

- Post-infarction Pericarditis, which is an inflammation of the sac-like covering of the heart that follows a heart attack.

Preventing Anteroseptal Myocardial Infarction (Heart Attack)

Improving health habits like changing your diet, getting more exercise, and stopping smoking can lead to better results after a heart attack. It’s very important for patients to learn about these changes when they leave the hospital. A referral to a heart rehab program can also be helpful.

It’s really important for patients to learn about eating healthier, losing weight, exercising regularly, and giving up smoking.

A heart rehab program offers many services over the long term. These might include health check-ups, supervised exercise sessions, help changing health risks, education, and counselling.