What is Carotid Cavernous Fistula?

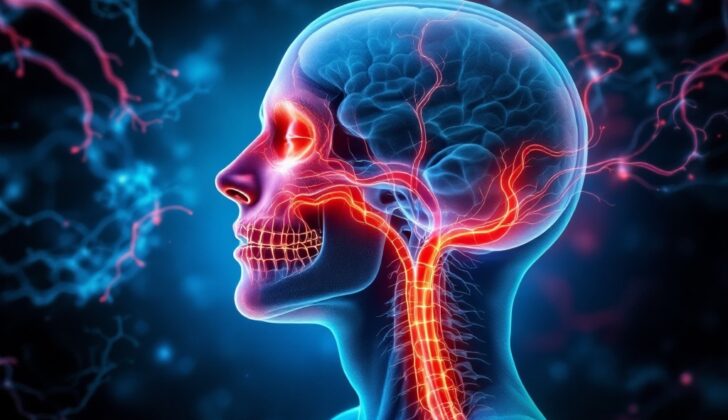

Carotid cavernous fistula (CCFs) is an unusual connection between the carotid artery, a main blood vessel in the neck, and the cavernous sinus, a blood-filled space at the base of the brain.[1] Symptoms of CCFs can vary depending on which nerves and blood vessels around the cavernous sinus are affected. These nerves can be responsible for movements and sensations in your eyes, face, and jaw.

CCFs can be grouped in different ways based on their features, origin, or the specific makeup of the unusual connection or ‘shunt’.

From a blood flow perspective, fistulas are classified as:

* Low flow fistulas, where blood moves through slowly, and

* High flow fistulas, where blood moves through quickly.

In terms of their causes, they’re classified into:

* Those that occur due to some form of injury, and

* Those that emerge spontaneously without a clear cause.

The most common way to classify CCFs is based on their physical structure, following the Barrow classification[2]:

* Type A fistulas are direct connections between the internal carotid artery and the cavernous sinus.

* Type B fistulas result from branches of the internal carotid artery that line the brain (dural branches).

* Type C results from dural branches from the external carotid artery, which supplies blood to the face, scalp, and neck.

* Type D result from dural branches from both the internal and external carotid arteries.

The treatment approach taken for CCFs often depends on the speed of blood flow through the fistula, the layout of the veins affected, and how quickly or slowly a patient’s symptoms are progressing.

What Causes Carotid Cavernous Fistula?

There are a few theories about how a carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF), which is an abnormal connection between the large artery in the neck (carotid artery) and a cavity filled with blood in the brain (cavernous sinus), forms.

One type, called direct CCF, is thought to happen as a result of a traumatic injury. This could be a tear in the artery due to a skull base fracture (see illustration), the force of a traumatic injury, or an accidental injury during a medical procedure like an endovascular intervention or a trans-sphenoidal procedure, which involves operating through the nose to reach the skull base. Surprisingly, they can also occur spontaneously. This can happen after the bursting of an aneurysm in the inner carotid artery, which is a balloon-like bulge filled with blood, or weakening of the arteries due to a genetic condition.

Another type, indirect CCF, is believed to be caused by a rupture in the small arteries that supply the dura, the outermost layer covering the brain and spinal cord, weakened by a defect like a genetic condition or other related diseases including high blood pressure. A different theory proposes that an increase in pressure in the cavernous sinus, such as what happens after blood clot formation, raises the risk of these small arteries tearing.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Carotid Cavernous Fistula

Carotid-cavernous fistulas (CCFs) are often caused by injuries, like fractures to the base of the skull, wounds from projectiles or slashes, or unintentional harm during medical procedures. These types of CCFs are typically seen in young men and are typically direct, high-flow fistulas, accounting for 70% to 75% of all CCFs.

- Injuries cause about 70% to 75% of all CCFs.

- These are most common in young men.

- These are usually direct, high-flow fistulas.

There are also CCFs that occur spontaneously, making up about 30% of all CCFs. These are usually due to a ruptured aneurysm or genetic conditions that make individuals more likely to have vascular injuries such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or fibromuscular dysplasia. They tend to be seen in older women and usually cause low-flow, type D indirect fistulas.

- Spontaneous CCFs make up about 30% of all CCFs.

- They are typically due to a ruptured aneurysm or genetic conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or fibromuscular dysplasia.

- These are most common in older women.

- Typically, these cause low-flow, type D indirect fistulas.

Signs and Symptoms of Carotid Cavernous Fistula

Understanding the patient’s history and the time when the symptoms began is crucial while investigating the cause of carotid-cavernous fistulas (CCFs). Fistulas that originate from traumatic high flows occur more acutely or suddenly.

The classic symptoms of CCFs often include bulging eyes (proptosis), a whooshing sound in one or both ears (ocular bruit), and swelling around the eye (chemosis). However, patients may also experience vision problems, pain in the orbit area, and issues related to the cranial nerves. Some low-flow indirect fistulas may be harder to distinguish based on the patient’s history. These might develop slowly and can sometimes start and stop depending on the flow rate.

- Bulging eyes (proptosis)

- A whooshing sound in one or both ears (ocular bruit)

- Swelling around the eye (chemosis)

- Vision problems

- Pain around the eye area

- Cranial nerve problems

Testing for Carotid Cavernous Fistula

The tests and scans a doctor uses to diagnose a Carotid-Cavernous Fistula (CCF) will depend on the symptoms you’re experiencing and if you’ve gone to a hospital emergency room or a clinic.

There are a couple of tests that a doctor might use. One is tonometry, and the other is pneumotonometry. Both of these can measure the pressure inside your eye. With CCF, you might have higher ocular pressure in the affected eye compared to your unaffected one.

Another method a doctor might use is a B-scan ultrasound or color Doppler. These can show whether a vein close to your eye, called the superior ophthalmic vein, is enlarged (dilated) or if there’s too much blood (congestion) in your orbit, the space in your skull where your eye is.

If a doctor thinks you might have a CCF, they might ask for a CT (Computed Tomography) or MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scan. These use powerful machines to make images of the inside of your body, and they can show the dilated superior ophthalmic vein, congestion in your orbit, or extraocular muscles becoming larger.

Doctors can also use other types of scans like CTA (Computed Tomography Angiography) or MRA (Magnetic Resonance Angiography). These are both good at detecting CCFs that cause problems with your vision.

The most reliable test to diagnose a CCF is called a cerebral angiogram. This scan can show the cavernous sinus (a hollow space at the base of your brain) filling up with blood through the fistula (the abnormal connection between an artery and a vein), where the blood from the fistula drains, and if there’s reflux (reverse flow) of blood into the veins on the surface of your brain. This is done after an injection into either your common carotid artery, external carotid artery, or internal carotid artery, which are major blood vessels in your neck.

Treatment Options for Carotid Cavernous Fistula

When it comes to managing carotid-cavernous fistulas (CCFs), a condition where there’s an abnormal connection between certain blood vessels in the neck and brain, various options are available. These methods depend on the speed of blood flow through the fistula. The aim is to completely block (or occlude) the fistula, and allow normal blood flow through the internal carotid artery (ICA), a major artery in the neck that supplies blood to the brain.

Spontaneous closure: In some cases of low blood flow CCFs, the problem may resolve on its own, with the fistula closing naturally. This outcome is expected to happen in about 20% to 60% of such cases.

Compression treatment: This is a non-invasive treatment option for CCFs with low blood flow. It involves pressing on the carotid artery in the neck several times a day for 4 to 6 weeks to promote clotting (or thrombosis) of the fistula. This is done by applying pressure with the opposite hand. However, this method works in only about 30% of cases.

Surgical intervention: Surgery is the most invasive option, but also the most definitive. Surgical techniques can involve stitching or clipping the fistula, packing the cavernous sinus (a blood-filled space on either side of the skull), or tying off the ICA. These methods have a success rate of between 31% and 79%. Radiosurgery, which uses focused radiation to treat the fistula, can also be an option. This technique can successfully treat the fistula in 75% to 100% of cases, but it’s not used for urgent cases as it can take months or even years to completely block the fistula.

Endovascular intervention: This is a first-line treatment option for CCFs and it involves inserting a device into the blood vessels to treat the fistula. It’s very effective, with a cure rate of over 80%. For high-flow CCFs, a route via the artery is preferred. After reaching the ICA, the fistula is blocked (or embolized) using a coil or liquid material. Alternatively, a stent (a small mesh tube) can be placed in the ICA or the artery can be completely blocked. For low-flow fistulas, a route via the vein is used to avoid the risk of stroke. A doctor can reach the cavernous sinus via the petrosal sinus or the facial vein. In complex cases, with possible blood clots or twisting of the blood vessels, doctors can access the cavernous sinus by inserting a needle directly into the superior ophthalmic vein after surgical exposure.

What else can Carotid Cavernous Fistula be?

For those experiencing symptoms of CCF or Carotid-Cavernous Fistula, it’s important to know that these symptoms may also be linked to other health conditions, including:

- Non-specific inflammation in the eye socket (orbital inflammation)

- Bleeding in the eye socket (orbital hemorrhage)

- Infection in the eye socket (orbital infection)

- Tumors in the eye socket (orbital tumor)

- Inflammation of blood vessels in the eye socket (orbital vasculitis)

- A blood clot in the cavernous sinus (cavernous sinus thrombosis)

- Thyroid disease

- Tumor affecting the cavernous sinus

Getting the right diagnosis for your symptoms is crucial. Doctors will do physical examinations, ask about your medical history, and conduct necessary tests to accurately determine which of these conditions may be causing your symptoms.

What to expect with Carotid Cavernous Fistula

Successful treatment of a fistula, or an abnormal connection between blood vessels, usually leads to the blood clotting in the surrounding area over time. This clotting, however, can take several weeks to months to fully happen after treatment. Symptoms like swelling and redness in the eye, bulging eyes, and problems with the cranial nerves usually improve within a few hours to days. Vision recovery may be influenced by various factors such as how much the fistula is flowing, when the treatment was given, and any signs of damage to the optic nerve or retina due to inadequate blood supply.

The likelihood of the fistula coming back is low, but patients can be monitored with a post-treatment imaging test of blood vessels to confirm the complete disappearance of the fistula.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Carotid Cavernous Fistula

Although Carotid-Cavernous Fistulas (CCFs) are typically not life threatening, they require timely treatment to prevent lasting damage to the affected eye. Despite the fact that a fistula could close on its own, patient symptoms can worsen due to a blood clot in the cavernous sinus – a major vein at the base of the brain. Complications resulting from endovascular embolization – a procedure to block off the CCF using materials such as a coil or balloon – are rare. However, they can include issues like eye muscle paralysis (ophthalmoplegia), blockage in the main vein of the retina (central retinal vein occlusion), blockage in the eye’s main artery (ophthalmic artery occlusion), and a stroke (cerebral infarction). The embolization process – inserting a substance to block the CCF – might not succeed if performed through the Superior Ophthalmic Vein (SOV) route. This can be due to delicate or blocked veins which might lead to complications such as vision loss.

Possible complications include:

- Worsening of symptoms due to blood clot in the cavernous sinus

- Eye muscle paralysis (ophthalmoplegia)

- Blockage in the main vein of the retina (central retinal vein occlusion)

- Blockage in the main artery of the eye (ophthalmic artery occlusion)

- Brain stroke (cerebral infarction)

- Failure of embolization through the SOV route

- Potential vision loss

Preventing Carotid Cavernous Fistula

As a patient, here’s what you should remember for your well-being:

Firstly, steer clear of contact sports. These games involve direct physical contact between players and can potentially lead to injuries.

Next, it’s crucial to manage high blood pressure. High blood pressure if left unchecked, can cause several health problems like heart disease.

Also, keep up with your periodic eye doctor visits. Having regular check-ups with an eye specialist (ophthalmologist) helps in early detection and treatment of any eye-related problems.

If your symptoms get worse, don’t delay a visit to the emergency room. They are equipped to look at your situation quickly and determine the right course of action.

Lastly, once you’ve received treatment, your doctor might ask for an imaging test (like an X-ray or MRI). This helps them see if the treatment was successful in fixing the anatomical issue (the fistula or abnormal connection between parts of your body) they were targeting.