What is Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis?

Constrictive pericarditis is a condition where the pericardium, which is the outer lining of the heart, becomes scarred and loses its flexibility. This loss leads to difficulties in the heart filling with blood properly. A less common version of this disease, known as effusive-constrictive pericarditis (ECP), involves both this hardening and a fluid buildup that puts pressure on the heart, similar to a condition known as cardiac tamponade.

The causes of this disease are often the same as for constrictive pericarditis, and they include heart surgery and, in places where healthcare resources are scarce, diseases like tuberculosis. The symptoms of ECP are similar to those of heart failure, especially a type of heart failure that affects the heart’s right side, and also resemble the symptoms of having too much blood in the body.

Effusive-constrictive pericarditis is usually a long-term (chronic) condition. Treatment typically involves surgery, though in some patients, addressing the root cause of the issue can alleviate both the fluid buildup and the hardening of the pericardium. Even so, most of the time, the exact cause of the disease is unknown. Thus, recognizing, diagnosing, and managing ECP is becoming more crucial as awareness of this condition grows.

What Causes Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis?

The pericardium, which is the protective layer around your heart, is made up of two layers. A small amount of fluid is naturally found between these two layers and this fluid helps reduce friction on the heart’s surface while also balancing the forces acting on the heart. It also helps transmit pressure changes within the chest to the heart. However, if too much fluid builds up between these layers, it’s known as an effusion. The excess fluid can come in various forms such as clear, bloody, or milky.

Diseases can cause inflammation of the pericardium, leading to scarring and fibrosis. Fibrosis means that the pericardium becomes less flexible. When this happens, it can’t expand as it should, which can push on the heart, and make it difficult to pump blood.

In developed parts of the world, effusions and constrictions can have many causes; including unknown origins, viruses, reaction to medical procedures, radiation, medications, autoimmune diseases, heart attack aftermath, cancer, physical trauma and kidney disease. In developing parts of the world, the most common reason is tuberculosis pericarditis, which is an inflammation caused by the tuberculosis bacteria. This is especially true in places where tuberculosis is widespread.

There are some specific factors seen in patients who ended up with constrictive pericarditis, an irreversible form of heart disease, after an acute pericarditis episode. These factors include having a fever, non-viral origin of pericarditis, large effusion, use of steroids, or not responding to certain medications.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis

Effusive-constrictive pericarditis, a heart condition involving fluid build-up and inflammation, impacts 2.4% to 14.8% of people, according to medical studies. However, these numbers might be low due to the lack of thorough tests done to confirm both fluid build-up and inflammation. One research found that out of 1,184 patients with inflammation of the heart’s lining and 218 patients with a critical condition called tamponade, 15 had effusive-constrictive pericarditis together. In patients with a specific type of inflammation caused by tuberculosis, 3% to 14% have this combined condition.

When looking at large groups of patients with constrictive pericarditis (i.e., rigid heart lining), the causes varied:

- For 42% to 49% of cases, the cause was unknown or viral

- Cardiac surgery caused 11% to 37% of cases

- Radiation therapy accounted for 9% to 31% of cases

- Connective tissue disorders caused 3% to 7% of cases

- Tuberculosis or other infections triggered 3% to 6% of cases

In a study of 500 cases experiencing a first episode of acute pericarditis (sudden inflammation of the heart’s lining), the incidence rate of constrictive pericarditis varied based on its underlying cause:

- For viral or unknown causes, the incidence rate was 0.76 cases per 1000 person-years

- For connective tissue disease or heart injury, the incidence rate was 4.40 cases per 1000 person-years

- For malignant pericarditis, the incidence rate was 6.33 cases per 1000 person-years

- For tuberculosis pericarditis, the incidence rate was 31.65 cases per 1000 person-years

- For purulent or infection-induced pericarditis, the incidence rate was 52.74 cases per 1000 person-years

Signs and Symptoms of Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis

Effusive-constrictive pericarditis is a heart condition that generally shows signs similar to increased body fluid levels. Common symptoms include veins in the neck swelling, accumulation of fluid in the abdomen, enlarged liver, swelling in the legs, and excess fluid in the lining of lungs. The affected individuals may also experience an increased heart rate due to decreased blood supply from the heart. This condition may cause various other symptoms like fatigue, low blood pressure, confusion, trouble breathing, and rapid breathing.

Some patients also have additional symptoms like fever, chest pain that increases with deep breaths, and a distinct sound known as a pericardial friction rub due to inflammation of the heart’s outer layer. Swelling of neck veins can also occur because of decreased pumping from the heart, leading to a backflow in the blood vessels.

Some signs can help differentiate effusive-constrictive pericarditis from chronic pericarditis. Pulsus paradoxus is a condition in which blood pressure drops by more than 10 mmHg while taking a deep breath. This can happen due to pressure on the left side of the heart resulting from the enlargement of the right side within the restricted space of the outer layer of the heart. In effusive-constrictive pericarditis, a usually undetectable fluid accumulation mimics signs of severe pressure on the heart.

Other signs include a third heart sound called a pericardial knock, which might be noticeable due to the sudden slowdown of blood filling the heart when the outer layer of the heart has stretched to its limits. There’s also a symptom called Kussmaul sign, which is seen as a rise in the pressure within the right heart chamber during inspiration due to the separation of chest and heart pressures leading to constant or increased pressure in the right atrium throughout the relaxation phase of the heart cycle. In severe heart compression, this doesn’t occur frequently as the chest pressures are still transmitted to the heart, ensuring an increase in blood return to the heart during inspiration and a reduction of right-sided backflow.

Testing for Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis

Echocardiography is a highly recommended tool for examining constrictive pericarditis, as it is very good at detecting fluid buildup. It allows doctors to see clear, unobstructed space between the inner and outer layers of the heart’s protective sac, and also to estimate the amount of this excess fluid. Furthermore, echocardiography can show an increased thickness of the heart’s sac, which is typical in cases of constrictive pericarditis. In this condition, doctors may spot specific motion patterns like the quick deceleration of filling up the heart’s chambers or the movement of the membrane dividing the heart towards the left ventricle.

Doppler recordings, a type of ultrasound, will show abnormal heart filling at the beginning of the relaxation phase, or diastole. There will also be changes in speed of the flow in the tricuspid valve (which separates the right atrium and right ventricle of the heart), depending on the breathing cycle. Another indicator that can help rule out this condition is something called M mode, where certain characterizing features of constrictive pericarditis would be missing.

Surgical removal of the pericardial fluid is one of the indicators of effusive-constrictive pericarditis – a more complicated form of this condition where the excess fluid coexists with constriction. After the fluid is removed, pressure in the right atrium of the heart continues to be high. Before fluid removal, tests will show that pressure is high and equal in all four chambers of the heart. This is evidenced by certain graphical indicators in ventricular pressure trends like the “square root sign” or “dip and plateau pattern.” When a patient has effusive-constrictive pericarditis, right atrial pressure features are intermediate – specific symptoms persist even after fluid removal that indicate constriction.

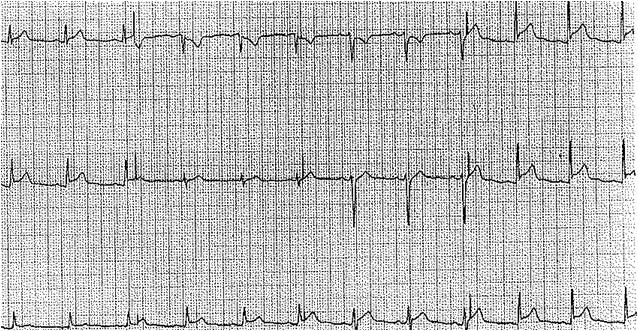

Chest X-rays are not very reliable for diagnosing effusive constrictive pericarditis, although an enlarged or flask-shaped heart may be evident if there is a large amount of fluid. An electrocardiogram, a test that measures the heart’s electrical activity, may show low signal strength in all leads due to fluid buildup interfering the electrical signals reaching the chest wall. In such cases, electric alternans occurs, which is a phenomenon of alternating amplitude of electric waves due to the heart’s rocking motion inside the fluid-filled sac during the respiratory cycle.

Treatment Options for Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis

The treatment for effusive-constrictive pericarditis, a condition affecting the tissue around the heart, is two-fold. Firstly, the symptoms can be managed using anti-inflammatory drugs like NSAIDs, colchicine, or steroids. However, caution should be exercised when using steroids, as they may worsen the condition in some patients. Additionally, diuretics can be given to alleviate symptoms related to fluid retention, but their use should be carefully managed due to the already decreased heart performance seen in these patients.

The second part of the treatment approach involves resolving the underlying cause, such as an infection or kidney dysfunction. Sometimes, a procedure called pericardiocentesis might be needed to relieve pressure on the heart. However, these measures are temporary fixes and the symptoms will persist until the affected tissue around the heart is surgically removed.

Therefore, the only definitive treatment is a surgery called pericardiectomy that involves removing the affected tissue. This procedure, however, comes with a high risk of complications and death. As such, it’s generally recommended only for patients who aren’t responsive to the medical treatments.

It’s worth noting that in some cases, effusive-constrictive pericarditis may resolve spontaneously after treating the underlying condition, or the symptoms may improve significantly with anti-inflammatory medications. For these patients, surgery can be deferred.

What else can Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis be?

When diagnosing effusive-constrictive pericarditis, doctors could consider a long list of conditions that may have similar symptoms. These may not necessarily associate with constriction, and can include:

- Aortic rupture or dissection (a tear in the aorta, the main blood vessel in your body)

- Heart attacks

- Cancer spreading to the heart

- Radiation damage to the heart

- Conditions affecting the immune system

- Diseases that affect the body’s connective tissue

- High levels of urea in the blood (uremia)

- Diseases causing abnormal deposits in organs (infiltrative disorders)

- Tuberculosis affecting the heart

- Simple fluid buildup around the heart (effusion)

- Acute inflammation of the tissue around the heart (acute pericarditis)

Constrictive pericarditis alone, which is a form of heart disease that restricts the heart’s ability to relax and fill, may present symptoms similar to effusive-constrictive pericarditis. Other conditions, too, can exhibit similar symptoms, like:

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy (a disease that makes the heart less elastic)

- Amyloidosis (abnormal proteins in the organs)

- Hemochromatosis (excess iron in the body)

- Other infiltrative disorders

Moreover, symptoms of effusive-constrictive pericarditis can also be seen in conditions like tricuspid regurgitation (leakage of the heart valve) and other causes of right heart failure, impacting how the body handles blood flow. In order to make the correct diagnosis, the doctor would carefully evaluate all these possible conditions.

What to expect with Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis

Without treatment, the results of effusive-constrictive pericarditis can be quite severe. Research has shown that the rate of needing surgical intervention, known as pericardiectomy, ranges from 40% to 100% for all causes of this condition. Alarmingly, the overall death rate was found to be as high as 50%. Additionally, patients might not only face complications from the syndrome itself and post-operative issues but can also die from the underlying disorder, such as metastases or tuberculosis.

The mortality rate associated with pericardiectomy is high, reaching up to 50% in cases where a bypass is required based on the experience of one institution. But for those who do not require a bypass, the mortality rate has been reported to be 0%. Factors like the severity of heart failure, exposure to radiation, post-heart surgery conditions, and the need for cardiopulmonary bypass further increase the overall risk of death.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis

If effusive pericarditis, a heart condition, is not treated, it can lead to severe health conditions, including symptoms of heart failure. However, with the right treatment and management, many people with effusive pericarditis can lead healthy lives.

Preventing Constrictive-Effusive Pericarditis

Effusive pericarditis usually shows up with symptoms that are hard to distinguish from those of other conditions. Nonetheless, patients must be aware of the crucial need to report any worsening shortness of breath, swelling in their arms or legs, weight loss or gain, as well as any pressure or pain they feel in their chest.