What is Pulmonic Regurgitation?

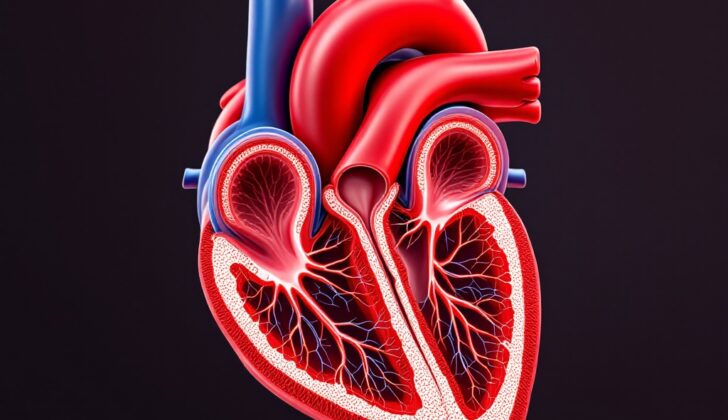

The pulmonary valve is a kind of heart valve that is found where the right ventricle (one of the four chambers of the heart) connects to the pulmonary artery. This valve is made up of three equally-sized leaflets, or flaps, which are connected together by three commissures, meaning the points where the leaflets attach to the wall of the artery.

Unlike some other heart valves, the pulmonary valve doesn’t have attachments to things called papillary muscles. If we took a closer look at the valve flaps, we’d see they are made up of five different layers, each with its own special name ranging from the ventricular end (closest to the heart) to the arterial end (closest to the artery).

During a heartbeat, this valve has a crucial job. It opens up fully when the heart is squeezing (which is known as systole) to let blood flow from the right ventricle to the lungs, where it will pick up fresh oxygen. Then, when the heart is relaxed and refilling with blood (a phase known as diastole), the valve closes completely. This stops any blood from flowing backward, which could cause problems.

But sometimes, this valve can become leaky, leading to a condition known as pulmonary regurgitation. The main reason this happens is usually because the ring around the valve (valve ring) becomes too wide. It’s a bit like how a door might not close properly if its frame becomes warped or stretched out.

What Causes Pulmonic Regurgitation?

Pulmonic regurgitation, a condition where the heart’s pulmonary valve doesn’t close properly, can be caused by several factors.

The condition can be a result of increased blood pressure in the lungs, known as pulmonary hypertension. This can be due to other problems with the lung’s blood vessels, clots in the lungs, or various lung diseases like chronic obstructive lung disease or interstitial lung disease, both of which affect the lungs’ ability to work properly. Sleep apnea, a sleep disorder where breathing repeatedly stops and starts, can also cause this.

Pulmonary hypertension can also occur when there’s left heart failure or problems with the aortic and mitral valves, which are valves in the heart. Other causes include diseases affecting other vital organs such as sarcoidosis (a disease involving abnormal collections of inflammatory cells), sickle cell disease (a group of inherited red blood cell disorders), and schistosomiasis (an infection caused by a type of flatworm).

The condition can also arise from problems with the pulmonary valve itself. It could be present from birth, or it could develop as a result of other medical treatments or conditions like endocarditis (an infection of the heart’s inner lining). Certain drugs and medical procedures can also cause damage to this valve.

Another cause of pulmonic regurgitation is when the ring-like part around the valve, known as the annulus, gets bigger. This can be due to increased blood pressure in the lungs, unknown causes, or conditions that impact the body’s connective tissue like Marfan syndrome. It may also occur after surgeries to treat a congenital heart defect known as tetralogy of Fallot.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Pulmonic Regurgitation

Pulmonic regurgitation is a condition that primarily occurs in two groups: young individuals who have had heart valve surgery for birth defects, and adults who have high blood pressure in the lungs for various reasons. It’s difficult to say exactly how common it is because there are so many different causes of high blood pressure in the lungs, which can then result in pulmonic regurgitation. It’s important to note that this condition can affect anyone, regardless of race or ethnic background. Whether it occurs more often in men or women depends on the specific cause.

Signs and Symptoms of Pulmonic Regurgitation

Pulmonic regurgitation is a condition related to the heart where the pulmonic valve doesn’t work as it should, causing blood to flow back into the heart. The cause of the condition greatly influences the patient’s history. The symptoms feel more severe when caused by lung disease or high blood pressure in the lungs rather than just a large volume of blood. Most patients only realize they have the condition when another illness has severe symptoms that bring them to seek help. If caused by bacterial heart infection, it may cause lung clots and high blood pressure, thus leading to severe heart failure. Symptoms of progression include fatigue, breathlessness during exertion, feeling bloated, and swelling in the lower extremities.

A common cause of the condition is the Ross procedure, which is a surgical operation to replace a diseased aortic valve. It’s the only intervention for a diseased aortic valve that can possibly extend the patient’s life span. A normal aortic valve is replaced with a part from the patient’s own heart. The downside is that it can cause backflow in the aortic and pulmonic valve. Pulmonic regurgitation in this case usually occurs 10 to 15 years after the operation.

Similarly, surgical repair for a birth defect called tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) can cause complications, including pulmonic regurgitation. This happens due to residual shunts or abnormalities after the operation.

Some physical indications include swelling of the neck veins with large V-waves, a sign called Lancisi, in patients with pulmonic regurgitation due to lung hypertension.

Auscultation, or listening to the sounds of the heart, can reveal the condition. Some of the findings can include a normal first heart sound, accentuated or inaudible pulmonic valve closure sound, and a systolic ejection click. Noteworthy is the audible third and fourth heart sound which increases with inspiration. Early detection can prevent heart murmurs, including the Graham Steell murmur, characterized by a high-pitched, blowing, and decreasing sound.

- Normal first heart sound (S1)

- Accentuated or inaudible pulmonic valve closure (P2)

- A sometimes audible systolic ejection click

- Audible third and fourth heart sounds (S3 & S4) that increase with inspiration

The progression of the condition can be divided into 4 stages according to the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guidelines:

- Stage A: Patients at risk for pulmonic regurgitation who have not developed it yet

- Stage B: Patients with no symptoms but with mild or moderate pulmonic regurgitation

- Stage C: Patients with no symptoms but with severe pulmonic regurgitation

- Stage D: Patients with pulmonic regurgitation that are starting to show symptoms

Testing for Pulmonic Regurgitation

An electrocardiogram (EKG), which is a test that records the electrical activity of your heart, can showcase certain signs of pulmonic regurgitation, a condition where the pulmonary valve in your heart doesn’t close properly and allows some blood flow back into the heart. If there’s no associated condition called pulmonary artery hypertension (high blood pressure in the lungs), the EKG might show a pattern called rSR in specific leads attached to the right side of your chest. This indicates extra load on the right side of your heart.

If the condition is due to pulmonary artery hypertension, you might see different EKG patterns. Tall P-waves suggest an enlarged right atrium (one of the heart’s chambers), an increased r to s ratio in the right chest leads and right axis deviation (all indicating thickening of the heart muscle and increased load).

A chest X-ray can also reveal if the pulmonary artery and the right chamber of your heart have gotten larger, but these signs don’t confirm the specific cause. Fluoroscopy, a type of imaging that shows real-time moving images of the body, might show strong pulsations of the main pulmonary artery.

Doctors often use echocardiography (an ultrasound of the heart) to detect conditions like pulmonic regurgitation. It can show if the right side of your heart is enlarged or thickened which can be a sign of pulmonary hypertension. It can also detect abnormal movement of the wall dividing the left and right chambers of the heart (the septum), which can mean your heart is struggling with higher volumes of blood. The movement of the pulmonic valve itself might point to the cause of the regurgitation. The lack of an expected wave pattern and an odd shape of the posterior leaflet (one of the three parts of the pulmonic valve) might suggest pulmonary hypertension too, while large A-waves might suggest narrowing of the pulmonary valve.

Doppler echocardiography, which uses sound waves to assess blood flow and pressure, is very accurate at detecting pulmonic regurgitation and helps doctors estimate its severity.

In instances of mild pulmonic regurgitation, doctors notice normal dimensions of the right heart chamber, with a small-sized regurgitant jet (a visual representation of the backward flow of blood). In moderate cases, the right heart chamber might seem normal or enlarged, with a regurgitant jet of medium size. With severe pulmonic regurgitation, the right heart chamber is enlarged (except in cases of acute or sudden onset pulmonic regurgitation) with a large-sized regurgitant jet.

In angiography, a diagnostic procedure where radiologists use special dye and imaging techniques to view your blood vessels, a condition like pulmonic regurgitation will show up as filling of the right heart chamber after injecting dye into the pulmonary artery – due to the backward flow of blood. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) test helps doctors assess the size of the pulmonary artery and the severity of pulmonic regurgitation.

Treatment Options for Pulmonic Regurgitation

The most important part of managing pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) – high blood pressure in the arteries supplying the lungs – is treating the condition causing it. For instance, treating a condition like mitral valve regurgitation/stenosis (a heart condition related to the malfunction of a heart valve) can help improve PAH. If someone is showing symptoms but is not suitable for surgery, we can manage their condition with heart failure medications such as diuretics (to reduce excess fluids in the body), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (to help relax blood vessels), and digoxin (to strengthen the heart muscle contractions and slow the heart rate).

Patients who develop pulmonic regurgitation (a condition where the pulmonary valve doesn’t close fully, causing blood to flow back into the heart) as a result of surgery to correct a heart defect known as Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), might benefit from a different treatment focused on the pulmonary valve. In such scenarios, replacing the faulty valve might be necessary. The replacement is often done with a porcine bioprosthesis (a pig heart valve) or a pulmonary allograft (a human donor valve). Thanks to recent advances, this valve replacement can now be done through a minimally invasive procedure called transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement. It’s proven highly effective in treating pulmonic regurgitation connected to congenital heart defects and those present from birth.

Surgical intervention is recommended in cases of:

- Severe symptomatic pulmonic regurgitation

- Asymptomatic (not exhibiting symptoms) severe pulmonic regurgitation along with at least 2 out of these 4 conditions:

- Enlarged right ventricle (a specific part of the heart)

- Raised pressure in the right ventricle

- Reduced ability to exercise

- Mild to moderate dysfunction in either the right or left ventricle

- Preference to use a bioprosthetic (artificial) valve instead of a mechanical one as it does not require long-term blood-thinning medications and can last longer (up to 15 years).

Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation, a minimally invasive procedure that places an artificial valve through a central vein, is recommended for patients with dysfunctional conduits in the right ventricular outflow tract (the path where blood exits the right ventricle) with a faulty prosthetic valve. This procedure has a success rate of about 94% to 98%, and the rates of complications during the procedure are between 3% to 6%. One of the main benefits of this procedure is that it requires a very short hospital stay (around 4-5 days), and patients can usually get back to their normal activities immediately after being discharged. The most important delayed complication that can occur is infective endocarditis, an infection of the inner layer of the heart.

What else can Pulmonic Regurgitation be?

Pulmonic regurgitation, a condition where the heart’s pulmonary valve doesn’t function properly, can occur due to various heart and lung diseases. Figuring out the underlying cause can be tricky and is crucial for treating pulmonic regurgitation. It’s especially important for doctors to differentiate between the specific sound (a ‘blowing decrescendo’ murmur) that pulmonic regurgitation makes, and a similar sound that another heart valve disorder, aortic regurgitation, makes.

In some cases, pulmonic regurgitation might not be the only heart valve problem. It can occur alongside issues with the mitral and aortic valves. In such situations, further tests like an echocardiogram (an ultrasound of the heart) are needed. This helps doctors see how severe each problem is.

What to expect with Pulmonic Regurgitation

The outcome or prognosis of a condition called pulmonic regurgitation, which is a leaky pulmonary valve in the heart, depends on how severe it is. Many patients who have this condition due to a repair for a heart condition called tetralogy of Fallot fare quite well. However, some may face delayed risk of death linked to dysfunction of the right side of the heart.

Patients with mild to moderate pulmonic regurgitation generally don’t experience a significant decrease in their lifespan. But if the condition is severe and results in a consistently high volume of blood in the right side of the heart, it might lead to the right side of the heart failing, irregular heart rhythms, and an increased risk of heart-related death.

In cases where pulmonic regurgitation is due to high blood pressure in the arteries supplying the lungs, known as pulmonary hypertension, the time of diagnosis and how long the person has had pulmonary hypertension greatly affects the outcome. Being diagnosed early with pulmonary hypertension, and having a cause for it that can be treated or reversed, usually results in a good prognosis.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Pulmonic Regurgitation

Severe pulmonic regurgitation, a heart condition where the pulmonary valve does not close properly, can lead to serious complications. These can include an enlarged right side of the heart, which can eventually result in heart failure and even sudden death. Other potential issues include a buildup of fluid in the liver due to heart failure, and blood clots that can block blood flow in the body. Abnormal heart rhythms are also not uncommon in cases of severe pulmonic regurgitation.

Following a procedure to replace the pulmonary valve, complications may include the new valve failing or becoming infected.

Typically, Here’s a list of complications can occur:

- Enlargement of the right side of the heart

- Right-sided heart failure

- Sudden cardiac death

- Fluid buildup in the liver due to heart failure

- Blood clots that can block blood flow

- Abnormal heart rhythms

- New valve failure following pulmonary valve replacement

- Infection of the new valve following pulmonary valve replacement

Recovery from Pulmonic Regurgitation

After surgery for pulmonic regurgitation (a condition where the blood flows backwards into the heart), the following steps are taken to help you recover and get back to normal:

* Anticoagulation: This is a kind of medicine that prevents your blood from clotting too much. If you have a bioprosthetic valve (a heart valve made from human or animal tissue), you’ll need to take this medicine for 3 to 6 months. If you have a mechanical valve (a heart valve made from man-made materials), you’ll need to take this medication for the rest of your life.

* Follow-up: After surgery, you’ll have an echo test (an ultrasound of your heart) to check how the new valve is working. You’ll then have another 2D echocardiogram (a special kind of echo that provides a detailed picture of your heart) between 1 year to 18 months later. After that, you’ll have more of these tests only if you start to experience symptoms.

Preventing Pulmonic Regurgitation

People who have mild to moderate pulmonic regurgitation, a condition where the heart’s pulmonic valve doesn’t close completely causing some blood to flow back into the heart, don’t need to limit their sports or physical activities. Currently, medical research does not provide any special suggestions to prevent this condition. Also, there’s no need for any specific changes to your diet unless you are experiencing symptoms of heart failure. If this is the case, cutting down on your salt intake can be beneficial.