What is Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block?

An atrioventricular block is a condition where the heart’s normal electrical pathways, connecting the sinoatrial node (SA node – the heart’s natural pacemaker) and the ventricles (the heart’s lower chambers), are not operating as they should. When there’s a third-degree AV block, it means there’s a total breakdown in communication between the top and bottom chambers of the heart.

Without the AV node (our heart’s electrical relay station) working properly, the SA node can’t control the heart rate effectively. This can lead to a reduction in the heart’s efficiency due to a lack of coordination between the heart’s chambers. This situation can turn critical if not treated immediately.

Most people with this condition will need to get a permanent pacemaker, a device that helps control the heart rate. In some cases, doctors might opt for temporary pacing while waiting to install the permanent pacemaker. Every patient’s situation is different and treatments are chosen on a case-by-case basis.

What Causes Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block?

The reasons behind AV (atrioventricular) blocks, a condition that interrupts the electrical signals between the heart’s chambers, can be quite diverse and apply to all levels of these blocks. Common causes include natural fibrosis (scar tissue), long-term heart diseases such as structural heart disease, acute ischemic heart disease (restricted blood flow to the heart), harmful drug effects, nodal ablation (procedure to treat abnormal heart rhythms), electrolyte imbalances, and post-operative heart block following procedures like a surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

AV blocks could also be related to Lyme disease or other systemic diseases such as collagen vascular disorders, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. These are all conditions that can affect multiple tissues and organs in the body.

Certain drugs, like those used to treat abnormal heart rhythms and digoxin, can contribute to a severe condition known as third-degree heart block.

An anterior wall MI (myocardial infarction) or heart attack, coupled with a complete heart block, can be life-threatening. About 5 to 10% of patients with this type of heart attack can develop complete heart block, but this may resolve within 2 to 48 hours. Generally, a complete heart block after a heart attack is uncommon. AV blocks can sometimes occur along with right coronary artery occlusion (blockage of one of the heart’s main arteries), but most of these cases resolve after revascularization, a procedure to restore blood flow.

AV block can also result after open-heart surgery, septal alcohol infusion (a treatment for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a type of heart disease), and percutaneous coronary interventions (nonsurgical heart procedures). Following aortic valve surgery, a complete heart block is more commonly observed in female patients and those with annular calcification, a type of degenerative process in the heart.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block

AV blocks are quite common, but the third-degree AV block, in particular, is quite rare. In general, very few people in the population have it – about 0.02% to 0.04%. Because this disease often doesn’t show any symptoms, the actual number of healthy people who have it is around 0.001%. However, in people who also have other diseases, the incidence is higher. For instance, about 1.1% of people with diabetes and 0.6% of people with high blood pressure that were cared for by the Veterans Health Administration were found to have a third-degree AV block.

Signs and Symptoms of Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block

Third-degree blocks are a heart condition that can show up in different ways for different patients. Usually, these patients feel tired, have chest pain, difficulty breathing, and may lose consciousness. They may be mentally confused and may have unstable blood pressure and heart rates. The severity of these symptoms can change based on other existing health conditions and the speed of their heart rhythm. If a patient with this block also suffers from a heart attack, they may experience additional symptoms like chest pain or difficulty breathing. Their medical history often includes other heart issues or risk factors like diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, and smoking.

Physical signs of this condition commonly include a slow heartbeat. Another sign might include what’s known as ‘cannon A-waves’, which are large pressure waves felt in the vein due to the simultaneous contraction of two chambers of the heart – the atria and the ventricles. When a patient’s heart rate drops below 40 beats per minute, they may also show signs of heart failure, difficulty breathing, and poor blood circulation – symptoms like sweating, fast breathing, confusion, shallow breath, cool skin, and slower blood return to the heart after being pumped out.

Other signs to look out for include new heart murmurs. These are important because there is a close link between complete heart block and certain heart conditions like cardiomyopathies, or the hardening or infection of certain heart valves. If there is co-existing heart failure shown by added heart sounds, swelling in the legs or abdomen, or an enlarged liver, immediate medical intervention is crucial.

Patients should also be observed for any signs of infection or skin rashes. These could indicate conditions like rheumatic fever, Lyme disease, and endocarditis, all of which can cause a heart block.

Testing for Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block

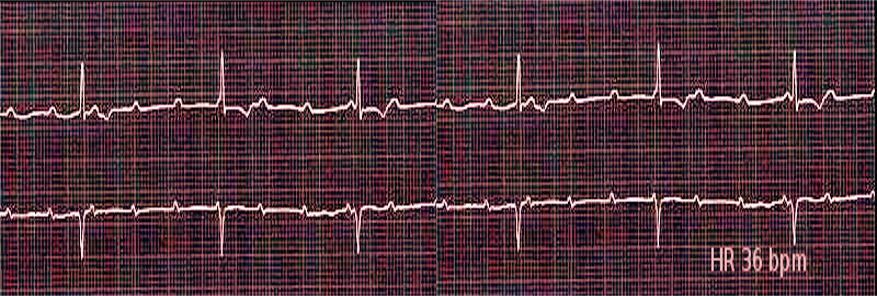

Patients suffering from a condition known as ‘complete heart block’ may sometimes show noticeable signs of discomfort or distress. After the doctor ensures the patient is in a stable condition, they proceed with a critical assessment called an electrocardiogram. This test, often called an ECG or EKG, allows them to examine the electrical activities of the heart.

The ECG scan will show how the upper chambers of the heart (atria) and lower chambers (ventricles) are functioning independently from each other. This is recognized through the unrelated patterns of the P wave (representing atrial activity) and the QRS complex (indicating ventricular activity). Typically, the P wave – or the atrial rate – should be faster than the QRS complex – the ventricular rate.

The QRS complex, depending on where the block’s location is, might have a narrow pattern (referred to as a ‘junctional escape QRS complex’) or a broad pattern (known as a ‘ventricular escape QRS complex’). The ECG test also evaluates if there are any signs of ‘ischemia’ – a term used to describe a reduced blood flow to the heart.

Your doctor might also check your basic metabolic panel, a set of blood tests, to correct any electrolyte imbalances and to check and manage glucose levels – which could be low due to beta-blocker toxicity. Beta-blockers are medications commonly used to manage heart issues.

Another crucial assessment for patients with complete heart block is testing for Troponin, a protein found in the muscles of your heart. Higher levels of Troponin in the blood signify some level of heart damage, for example, a heart attack. For patients who are on the medication Digoxin, a test will be carried out to rule out potential toxicity from the medication.

Moreover, a chest X-ray will be done to check for any other diseases related to the heart or lungs. A complete blood count, a test that provides information about the cells in a person’s blood, is also usually ordered to evaluate overall health and detect a wide range of disorders.

Treatment Options for Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block

When a patient has a heart rate that’s too slow (a condition known as bradycardia) and causing noticeable symptoms, doctors typically start treatment with a medicine called atropine. However, this may not always be effective, especially in cases where there is a complete block in the heart’s electrical signals. Other medications like dopamine and epinephrine can be used, but these are only temporary measures and might also not work in severe cases.

If medications aren’t working, the next step is usually to use a pacing device, which sends small electrical pulses to the heart to help it beat at the right pace. There are a few different types of pacing devices. One type, called a transcutaneous pacemaker, can quickly be applied to the skin. But if this doesn’t work, the doctor might need to install a more permanent pacemaker.

Pacemakers are often recommended for patients with certain types of heart block. However, they should not just be used automatically without considering other factors. These include the patient’s blood pressure, their symptoms, and the specific nature of their heart block. If the underlying cause of the heart block is not treated, a pacemaker may not solve the problem. So, treating the root cause should always be a priority.

Installing a pacemaker is not without risks. Complications can arise related to the implant itself – such as the device moving, running out of battery, or not working as intended – as well as the care after the surgery. For example, certain activities could accidentally dislodge the device, and there are risks of infection, blood clots, or heart damage. So, the use of temporary pacemakers should be kept to a minimum to avoid these problems.

Guidelines suggest that temporary pacemakers should not be used as a reflex response to heart block and should only be the last resort when other treatments are not enough. They should mainly be used in severe cases of heart block without a stable back-up heart rhythm, life-threatening low heart rate, or during certain procedures if the heart rate drops.

For patients with a stable blood pressure or ones that have a slower but normal heart rhythm, simply closely monitoring the patient’s heart might be enough.

When a permanent pacemaker is definitely needed, experts recommend installing it as soon as possible. This is because using a temporary pacemaker before a permanent one can increase the risk of infection and other complications. For patients with heart block due to a heart attack, a temporary pacemaker might be used during a procedure to restore blood flow (a process called reperfusion). The installation of a permanent pacemaker is typically more common in those with a front (anterior) heart attack, rather than a lower (inferior) heart attack.

Lastly, it’s crucial to restore blood flow as soon as possible in heart attack patients with heart block, as this increases the chances of the heart’s natural rhythm returning.

What else can Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block be?

To diagnose a third-degree heart block, you would typically use a specific type of heart test called a 12-lead ECG. This condition is usually identified by the total disconnection between the heart’s chambers, with the top chambers (atria) beating faster than the bottom chambers (ventricles). However, it’s important to make sure that this condition isn’t actually another problem in disguise.

For instance, some heart rhythm disorders can mimic third-degree heart block. These include idioventricular rhythms, where the ventricles beat faster than the atria, as well as certain second-degree heart blocks and high-degree AV blocks.

To be sure that we’re dealing with a real third-degree heart block and not an imposter, doctors will often use additional ECGs or longer rhythm strips. These tools can help clarify the diagnosis and confirm the presence or absence of third-degree heart block.

What to expect with Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block

The outlook for long-term recovery from third-degree AV block, a type of heart block, isn’t clearly understood because it often requires immediate treatment. The recovery likely depends on the severity of the person’s other health conditions and how serious their symptoms are when they arrive for medical attention. Some heart blocks can be reversed, such as those from a heart attack, by restoring blood flow to the heart, or those caused by Lyme disease with antibiotic treatment.

Interestingly, it’s believed that very serious types of AV block could indicate a poor recovery outlook for patients suffering from a heart attack. This belief is also backed by recent studies.

An important point to consider is that the presence of a complete heart block, especially during a heart attack, can increase the risk of death. At the same time, this issue is more common in people with inferior heart attacks than anterior heart attacks. This means that temporary pacing is often used more in inferior heart attack patients, but patients with anterior MI needed permanent pacemaker treatment more often. Also, the death risk with complete heart block is higher in anterior MI patients than in inferior MI ones.

Medical experts recommend placing a pacemaker in patients with persistent third-degree AV block. However, what counts as “persistent” is often up to the doctor to determine. Survey data from Italy shows just over 21% of about 24,000 patients received pacemaker treatment for third-degree AV blocks. Although a pacemaker is an ultimate treatment for patients with this type of heart block, it does come with its own health challenges. A 2017 study found that patients with AV block are more likely to develop heart failure than those without it. This risk is present both in the short term (over six months) and long term (6 months to 4 years), and it might be due to the heart’s reliance on frequent RV pacing.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block

People with a condition called third-degree heart blocks are at risk of having decreased blood flow due to an abnormally slow heart rate and lower heart function. This can lead to fainting, falls and potentially even injuries to the head. If they are critically ill, they might not be able to prevent food or liquid from going into their lungs, feel like vomiting, possibly breathe in foreign substances, and can become disoriented or confused.

There are also potential complications relating to the treatment. In the short term, these may include the incorrect placement or dislocation of a device called a pacemaker lead, and potentially damage to the heart. Over the long term, the pacemaker itself can contribute to heart failure. As with the outcome of third-degree heart block, these complications often depend on a person’s overall health and their body’s ability to counterbalance their heart’s reduced capability.

Common Side Effects:

- Decreased blood flow

- Fainting

- Falls

- Potential head injuries

- Difficulty preventing food or liquid from going into lungs

- Feeling of nausea

- Chance of breathing in foreign substances

- Possibility of disorientation or confusion

- Incorrect placement or dislocation of a pacemaker lead

- Potential damage to the heart

- Pacemaker contributing to heart failure

Preventing Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block

Teaching patients about their condition is key to reducing the overall impact of the disease. Conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure, while not directly causing the problem, have been linked to an increased occurrence of the third-degree heart block, as previously discussed. So, by focusing on improving overall heart health, there could be an improvement in the patient’s condition.

After the installation of a permanent pacemaker, it’s important that patients are advised about caring for their wound and given instructions for after surgery. They’re usually advised to avoid driving for about two to three weeks and to use a sling for their arm during the night and at intervals during the day. This helps prevent any movements that could affect the shoulder. They should also be taught about devices that can cause significant interruptions to the pacemaker, although this is less of a concern with the newer versions of pacemakers available today. It’s important that patients are also informed about the need for regular check-ups for their pacemaker, which will include tests for things like the function of the lead wire, the lead thresholds (which is the minimum amount of electrical energy required to stimulate the heart), and the life remaining in the battery.