What is Tricuspid Atresia?

Tricuspid atresia is a condition present at birth where the heart’s tricuspid valve doesn’t form, leading to a lack of connection between the right upper and lower chambers of the heart. This absence causes a blue or purple tinge to the skin, lips, and nails, also known as cyanosis. There are different types of this condition, and the symptoms can vary depending on how the blood flow to lungs is affected. This condition generally occurs due to issues in the development of the heart while the baby is still in the womb, and we don’t currently know of any specific genetic factors that cause it. Without treatment within the first year of life, this condition has a high risk of being fatal.

Since this condition can vary in structure, with some patients showing blockage to the lungs, doctors will typically do an in-depth examination to understand the severity of the condition and how it’s affecting blood flow in the patient’s body. Depending on the specific characteristics of the condition, the doctor may recommend different courses of action to restore normal blood flow. Taking into account the possibility of severe long-term complications, these patients often receive intensive care, followed by constant check-ups to ensure they maintain a good quality of life.

What Causes Tricuspid Atresia?

Tricuspid atresia, a heart condition, has origins that aren’t completely known. However, it’s been found that it happens when there’s a disruption in the normal development of particular heart valves (the atrioventricular valves), which originate from a certain heart structure (the endocardial cushion). For most patients, the affected area of the heart (the tricuspid inlet) appears as a small indent in the right upper chamber of the heart (the right atrium), kind of like a muscular form.

In rarer cases, the leaflets (the flaps of the heart valve) partially separate, which leads to the creation of thin, veil-like partitions or membranes. This is similar to what’s seen in a variant of the condition known as the Ebstein type.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Tricuspid Atresia

Congenital heart disease is quite common, with 81 cases in every 10,000 births. One type, called tricuspid atresia, is the third most common among these diseases, affecting 1.2 out of 10,000 live births. Tricuspid atresia doesn’t favor one gender over another, affecting both boys and girls in equal measure. It’s important to note that it’s not common to see multiple cases within a family. When it does happen though, it’s thought to be passed down in a way that both parents’ genes contribute to the child having the disease.

Signs and Symptoms of Tricuspid Atresia

In simple terms, how a patient presents with a certain condition depends on a few factors. These include how much the pulmonary artery is blocked, if there’s a hole in the wall separating the two lower heart chambers (known as VSD or Ventricular Septal Defect), and how the main arteries are structured.

Patients with a blockage in the pulmonary artery usually show signs of cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the skin) after birth, which typically becomes noticeable after the ductus arteriosus (a blood vessel present before birth) closes. When doctors examine these patients, they may notice decreased pumping action of the right side of the heart. Sometimes, they may feel a vibration when touching the chest (a thrill), hear heart murmurs or a continuous sound when listening with a stethoscope. Older patients might develop clubbed fingers due to long-term low oxygen levels.

On the other hand, patients without a blockage in the pulmonary artery, but with a VSD, may have significantly more blood flow to their lungs. These patients don’t typically show signs of cyanosis right after birth. Signs of the condition often become noticeable when there’s a drop in the resistance to blood flow in the lungs, leading to more blood flowing into the lungs than usual. This might result in symptoms of heart failure such as fast breathing, trouble feeding, and slow growth. When examined, these patients might show signs of fast heart rate, large liver, and fast breathing, especially when the lungs are flooded with blood.

- Persistent blue or purple coloration of the skin (cyanosis)

- Diminished heart function

- Vibration felt when touching the chest (thrill)

- Abnormal heart sounds or continuous murmur

- Clubbing of the fingers in older patients

- Rapid heart rate (tachycardia)

- Rapid breathing (tachypnea)

- Liver enlargement (hepatomegaly)

- Difficulty feeding and poor growth

Testing for Tricuspid Atresia

Nowadays, thanks to improvements in ultrasound scans during pregnancy and fetal heart check-ups, most cases of tricuspid atresia (a heart defect) are detected before birth in the United States. This defect can be identified as early as 11 weeks into the pregnancy, but it is typically spotted around the 22nd week. According to a recent large study, the number of prenatally diagnosed tricuspid atresia cases ranges between 0.2 and 0.9 per 10,000, and there seems to be an increase in the detection of this condition over time.

If the condition wasn’t diagnosed during pregnancy, it may be identified after birth during a critical congenital heart disease screening if the baby has low oxygen levels or a heart murmur. A chest x-ray could also show signs of this condition, like less blood flow in the lungs or an enlarged right atrium. Furthermore, an electric heart rhythm test, known as an ECG, may show an unusual leftward tilt (-30 to -90 degrees), which is a characteristic sign of this condition. The ECG could also detect decreased right ventricle activity and potential evidence of left ventricle enlargement.

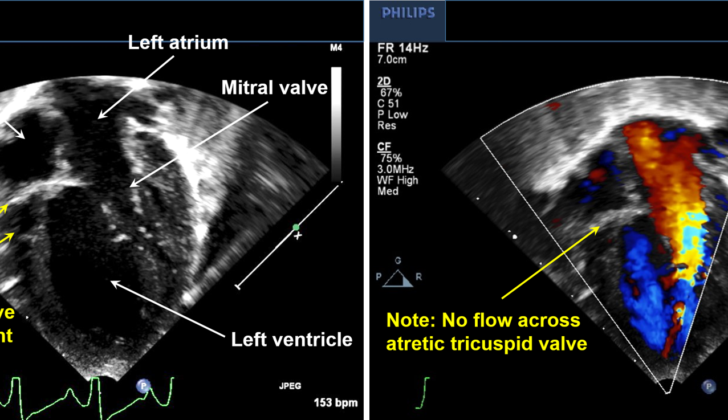

Echocardiography, a type of ultrasound test, is the key diagnostic tool for tricuspid atresia. It may reveal the absence of the tricuspid valve and unequal sizes of the ventricle chambers, with the left one being larger than the right. This test also highlights the absence of blood flow across the tricuspid valve.

Usually, there’s no need for cardiac catheterization, a procedure that uses a long, thin tube to check the heart, for diagnosing this condition. However, in rare cases where the partition (atrial septum) between the two heart chambers restricts blood flow from the right to the left chamber, a specific type of cardiac catheterization known as a balloon atrial septostomy might be necessary. Genetic testing could also be considered due to links between this condition and various genetic abnormalities like trisomies, VACTERL syndrome, and 22q11.

Treatment Options for Tricuspid Atresia

The initial treatment of this condition is centered on stabilizing the patient. The use of a particular drug called prostaglandin is essential right after birth for patients with severe symptoms or a very small ventricular septal defect (VSD), which is a hole in the wall separating the two lower chambers of the heart. It improves blood flow to the lungs. Patients who are a little older and show signs of heart failure might need medications to get rid of extra fluid in the body.

In cases where one of the two ventricles (chambers that pump blood out of the heart) isn’t working (specifically, the tricuspid, or right ventricle), a series of surgeries are performed. The goal of these surgeries is to ensure that there’s enough blood flowing to the lungs and the rest of the body. The exact nature of the first surgery depends on several factors including the structure of the main blood vessels leaving the heart, whether there’s any obstruction to blood flow, and the size of the VSD, if it is present.

Patients With Blockage to Blood Flow in the Lungs

For patients with a blockage in blood flow to the lungs, the first step is to ensure enough blood is reaching the lungs. This is usually achieved by surgically creating a connection (or shunt) between a large artery leaving the heart and one of the pulmonary arteries (which carry blood to the lungs).

Patients Without Blockage to Blood Flow in the Lungs

Patients with no obstruction to blood flow in the lungs might need a surgical procedure to limit excessive blood flowing into the lungs. In some cases, a small VSD might naturally limit the blood flow to the lungs, resulting in a balanced blood flow in the body. For these patients, no initial surgery might be required.

Patients with a Specific Type of Heart Defect and Obstruction to Blood Flow from the Heart

Certain patients have a VSD that obstructs blood flowing out of the heart through the aorta (the body’s largest blood vessel). For these patients, the first surgery might involve either enlarging the VSD or creating a connection between the pulmonary artery and aorta.

Second and Third Stages

The second stage involves creating a connection between a large vein carrying oxygen-poor blood from the body and the pulmonary artery. This surgery is typically performed when the patient is around 6 months old.

The third stage is known as the Fontan procedure, which connects a large vein bringing oxygen-poor blood from the lower part of the body to the pulmonary arteries. This procedure is typically performed when the patient is between ages 2 and 3. In some cases, where the remaining ventricle is failing, the patient might eventually need a heart transplant.

What else can Tricuspid Atresia be?

When trying to diagnose a specific medical condition, there are other possible conditions that professionals need to consider. These are conditions that might present with similar symptoms, such as turning blue (cyanosis) and decreased blood flow to the lungs. The different diseases that doctors would consider are:

- Isolated pulmonary atresia

- Tetralogy of Fallot (a serious heart condition)

- Atrial septal defect (a hole in the wall that separates the top two chambers of the heart)

- Pulmonic stenosis (narrowing of the pulmonary valve)

- Pulmonary atresia (a defect of the pulmonary valve)

- Tricuspid stenosis (narrowing of the tricuspid valve)

These conditions could produce similar symptoms, making them important to consider in the diagnosis process.

What to expect with Tricuspid Atresia

Without surgery, most patients face a high risk of dying within the first year of life. However, thanks to early diagnosis and effective surgical procedures, people with tricuspid atresia (a heart defect) often survive into adulthood and maintain a good quality of life. The risk of death associated with the Fontan procedure, a specific type of heart surgery, is consistently below 2%.

In a detailed study in 2004, which looked specifically at people with tricuspid atresia from 1971 to 1999, it was found that survival rates were 82%, 72%, and 61% at 1, 5, and 20 years, respectively.

Thanks to improvements in surgical techniques and medical innovations, surgical outcomes have significantly improved. A recent study examining outcomes for a range of heart conditions, including tricuspid atresia, showed a 92% survival rate after 15 years without needing a transplant, and an 87% success rate with the Fontan procedure.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Tricuspid Atresia

The process of treating tricuspid atresia involves multiple stages and each has short and long-term complications. Between the first and second stages is where the highest mortality rate is seen. For patients who get a BT shunt, which is a type of heart bypass, there’s a risk of blockage in the shunt. Research has shown that even with modern techniques, around 12% of patients who get a modified BT shunt don’t survive their hospital stay. After leaving the hospital, there’s a further 6% mortality rate. Non-heart complications, such as gut tissue death and strokes, were also found to frequently occur after a BT shunt.

- Interstage mortality is highest between the first and second treatment stages

- 12% mortality for patients getting a BT shunt

- Additional 6% mortality rate after hospital stay

- Non-heart complications like gut tissue death and strokes

Common complications after constraining the pulmonary artery, which controls blood flow to the lungs, include the band moving and becoming too loose, requiring further medical intervention. Additionally, patients may face narrowing or distortion of the pulmonary artery. A recent study showed that using double bands or using smaller bands for a longer period may result in needing several pulmonary artery treatments.

Glenn surgery, named after the surgeon who developed it, has generally excellent outcomes with a less than 1% mortality rate and a five-year survival rate of 87%. But, despite having a low rate, the deadliest complications from this procedure are blood clots and clot-related events.

Single ventricle treatment could lead to both systolic and diastolic dysfunction i.e., difficulty in the heart pumping out or filling up with blood respectively. Newborns often suffer heart overload after a BT shunt, possibly causing leaky heart valves and too much stress on the heart muscle. Long term, abnormalities in heart function may alter the heart’s workload and heart mass, affecting heart performance over time. Advanced dysfunction of the heart’s pumping action is a key factor to chronic failure of the Fontan procedure. If this happens, the patient might need a heart transplant.

- Long-term complication after Fontan surgery – heart’s inability to pump blood effectively,

- Risk of Fontan procedure failure

- Potential heart transplants in case of advanced failures

Irregular heartbeats are common after the Fontan procedure, especially fast heart rhythms often caused by stitches in the right upper chamber of the heart that may disturb the normal rhythm. Critical heart rhythms are less often seen in these patients. Blood clot blocks, however, are a potential concern with about 11% of patients having this complication.

The condition of high protein levels in a patient’s feces is a well-documented complication and occurs in 5% to 12% of patients after the Fontan procedure. This can affect the patient’s nutritional status over the long term. Treatment approaches include limiting fluid build-up, replacing proteins and practicing a high-protein, low-fat diet.

Another possible long-term side effect for patients who have undergone the Fontan procedure is plastic bronchitis, which is characterized by thick secretions in the breathing tubes. This occurs in around 4% of patients and is thought to occur due to protein leakage through connections between lymph vessels and bronchial tubes.

Certain patients might experience cyanosis, or blue skin, due to different factors. They might find relief through medical interventions.

Tricuspid atresia can lead to various long-term complications, including Fontan-associated liver disease (characterized by liver scarring and cirrhosis), kidney problems, growth issues, mental and developmental issues, and reduced physical endurance.

- Irregular heartbeats, especially rapid rhythms

- Blood clot blocks in around 11% of patients

- 5% to 12% of patients after Fontan procedure may face protein leakage

- Plastic bronchitis seen in around 4% of patients with Fontan procedure

- Manifestation of blue skin due to certain factors

- Long-term effects might include liver disease, kidney problems, growth issues, mental and developmental problems, less physical endurance

with tricuspid atresia with left axis deviation.

Preventing Tricuspid Atresia

People who have tricuspid atresia need to have regular check-ups with a heart doctor who specializes in congenital heart disease, which is a heart condition that you’re born with. These check-ups might be with a pediatric cardiologist (a heart doctor for children) or with a specialist in adult congenital heart disease (heart conditions you’re born with but continue into adulthood). How often you need to go for these check-ups depends on the stage of your single ventricle treatment, but if you’ve had a Fontan procedure (a kind of surgery that helps your heart work better), you’ll probably need to have a check-up at least once a year.

During these check-ups, the doctor will ask you about your medical history and will do a physical examination. This helps them check for any complications you might be having. For example, if you have jugular venous distension (when your jugular vein in your neck becomes swollen) and hepatomegaly (when your liver gets bigger than normal), it could mean that there’s a blockage in your heart or your heart’s not pumping as well as it should be. If you have swelling in your body or diarrhea, it might mean you have Protein-Losing Enteropathy (PLE), a condition where the body loses too much protein. If you’ve been having difficulty breathing, it could suggest heart failure. The doctor will also ask about if you’ve been having palpitations (a feeling that your heart is beating too hard or too fast), which could suggest you have an abnormal heart rhythm.

Besides talking to the doctor and having a physical examination, you’ll likely need to have some tests done every-yearly. These tests include an ECG (a test that checks how your heart is working by measuring its electrical activity) and a transthoracic echocardiogram (a test that uses sound waves to make pictures of your heart). Every 3 to 4 years, you’ll have a deeper dive into how your heart (and the rest of your body) is doing. This could include a 24-hour Holter monitor (a machine that you carry with you that records your heart’s rhythm), an exercise stress test (a test that measures how your heart responds to being pushed), a test to check the level of a certain protein in your blood, and scans of your heart. You might also need blood tests and imaging tests to see how other organs in your body are doing.

For people with tricuspid atresia who’ve had surgery, they can reach the age where they might want to consider getting pregnant. However, for women who’ve had the Fontan procedure, getting pregnant comes with more risks. It can make heart problems, like an abnormal heart rhythm or heart failure, more likely, as well as increase the risk of blood clots. It’s important to discuss these risks with your heart doctor and your obstetrician, who is a doctor that specializes in pregnancy and childbirth. You’ll want to make sure both your heart and the rest of your body are in the best possible shape before getting pregnant.