What is Breast Lymphatics?

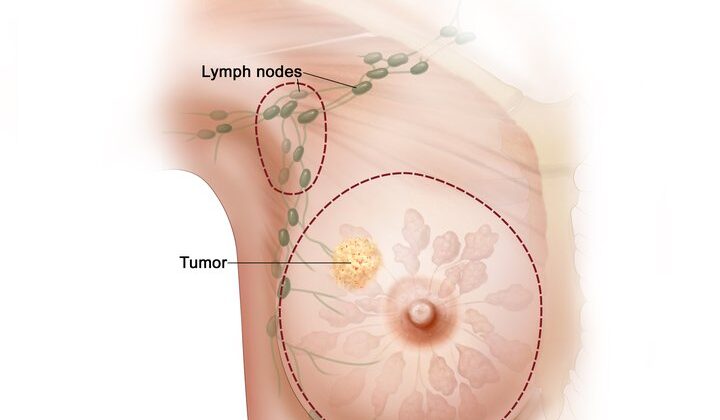

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer diagnosed in women all over the world. Whether lymph nodes are involved or not plays a significant role in predicting the outcome and planning the treatment for breast cancer. Lymphatic channels, small tubes that carry lymph fluid, converge under the nipple, forming a network known as Sappey’s plexus. The axillary lymph nodes, which drain the breast tissue about 75% of the time, are categorized into three groups based on their position relative to the large chest muscle, the pectoralis major. The first group, or level one, are located to the side of this muscle, the second group, or level two, are situated behind the muscle, and the third group, or level three, are by the inner side of the muscle. Interestingly, the lymph node between the pectoralis major and another muscle, the pectoralis minor, has its own name – it’s known as the Rotter’s node. About 5% of the time, the internal mammary lymph node, situated under the breastbone, is the main node that drains the breast. The rest of the time, any excess fluid is drained into a combination of the axillary and internal mammary lymph nodes.

What Causes Breast Lymphatics?

When breast cancer cells start to invade and break through a barrier called the basement membrane in the lymphatic channels, there’s a chance they could spread elsewhere in the body. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a type of breast cancer where the cells have not yet punctured this barrier. However, studies show that in 10% to 20% of DCIS patients, invasive cancer cells are still found in the breast tissue removed during their surgery.

If the cancer cells block the skin’s lymphatic channels, it can cause skin swelling, which is commonly known as ‘peau d’orange’. This puffy, orange-peel-like skin is a classic sign of a type of breast cancer called inflammatory breast carcinoma.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Breast Lymphatics

Each year in the United States, over 180,000 women are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, and over 40,000 sadly lose their lives to this disease. Men make up less than 1% of all breast cancer diagnoses. The likelihood of a woman developing breast cancer increases as she gets older. For example, a woman who is 30 has a 1 in 257 chance of developing this disease, while a 60-year-old woman’s chances increase to 1 in 24. The chances that the cancer will spread to the lymph nodes also go up, depending on the size of the tumor, if the cancer has invaded the lymph vessels, and the aggressiveness of the cancer. Axillary (armpit) lymph node metastasis happens in less than 1% of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS), a type of non-invasive breast cancer.

- More than 180,000 women are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer each year in the United States.

- More than 40,000 women die from breast cancer each year.

- Less than 1% of all breast cancer diagnoses are in men.

- The risk of developing breast cancer increases with age—for instance, a 30-year-old woman has a 1 in 257 chance, but a 60-year-old woman has a 1 in 24 chance.

- The chance of cancer spreading to the lymph nodes increases with the size of the tumor, if the cancer has invaded the lymph or blood vessels, and the aggressiveness of the cancer.

- Axillary lymph node metastasis,a type of breast cancer spread, is present in less than 1% of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS) cases.

Signs and Symptoms of Breast Lymphatics

When checking the lymph nodes in the breast during a physical examination, the doctor will most likely have the patient sit upright, either with their arms supported at the sides or with their hands on their hips. This is to ensure the best feel for any changes in the nodes. In addition to the axillary (armpit) nodes, the doctor will also examine the nodes above and below the collarbone, known as supraclavicular and infraclavicular lymph nodes, respectively.

Testing for Breast Lymphatics

If a lymph node looks unusual during a physical examination or a mammogram, it can be further tested with an ultrasound. Specific features that might raise concern on an ultrasound include enlarged nodes, thickening of the outer layer of the node, and loss of fatty tissue within the node. If a node looks concerning on the ultrasound, a biopsy should be performed. This can be either a core-needle biopsy or a fine-needle aspiration (FNA). During a core-needle biopsy, a small marker is often inserted to make it easier to locate and possibly remove the node during surgery if it turns out to be harmful.

Fine-needle aspiration is a particularly reliable method, being able to confidently identify suspicious lymph nodes 90% of the time and being 100% accurate in confirming when a node is harmless. If an MRI is done for diagnosis, any lymph nodes that show up brighter may need further assessment with ultrasound and possibly a core-needle biopsy. A special type of imaging called lymphoscintigraphy can help identify specific groups of lymph nodes and find their precise locations before surgery.

For patients whose physical examinations do not show any negative signs related to the lymph nodes, a sentinel node biopsy can be performed. This is a surgical procedure where the first few lymph nodes into which a tumor drains (called sentinel nodes) are removed and tested for cancer.

Treatment Options for Breast Lymphatics

A sentinel lymph node biopsy is a procedure used to check the presence of cancer in the first lymph node (sentinel node) draining a tumor. This procedure is commonly used in breast cancer patients who do not present any physical signs of cancer in the lymph nodes. The biopsy is performed during a partial or full mastectomy — surgeries for removing part or all of the breast tissue.

Before starting the procedure, a radioactive substance or a blue dye, or a combination of both, is injected into the tissue beneath the areola (the colored area around the nipple). These substances help the surgeon locate the sentinel lymph nodes, which are then removed during surgery. On average, 1 to 4 sentinel nodes, typically around 2 in number, are removed. If there are any nodes that appear suspicious, these are removed as well.

In some cases, further removal of lymph nodes (a procedure called axillary lymph node dissection, or ALND) isn’t necessary. This typically applies when the patient has small (T1-T2) tumors, 1-2 positive nodes without cancer cells outside the node, and is undergoing either full breast radiation or certain types of drug therapy.

On the other hand, in cases of larger (T3-T4) tumors, mastectomy, more than two positive nodes, use of certain types of breast radiation, presence of suspicious or palpable nodes, or pre-treatment with chemotherapy, the ALND approach is not suggested.

Some clinical trials have shown that finding microscopic cancer cells in lymph nodes (detected through a staining method), does not affect survival rates or the risk of cancer recurrence in the same area. Thus, the presence of these microscopic lesions does not alter the treatment plan.

In cases of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), where there is an uncontained cancer cell formation, the occurrence of disease in axillary lymph nodes can vary. However, it’s not customary to consider a sentinel lymph node biopsy for DCIS unless a mastectomy is being performed, due to the potential for finding invasive cancer.

Various factors can influence the likelihood of finding cancer in additional nodes when the sentinel node is positive. These factors include tumor and lymph node metastatic lesion size, presence of cancer cell spread into blood vessels, hormone receptor and HER2 status, grade of cancer, and the patient age at diagnosis.

Axillary lymph node dissection is essential in cases of advanced or inflammatory cancer, when a positive node is found in patients undergoing mastectomy or certain types of breast radiation, or when chemotherapy was given before surgery. In patients with more than three positive nodes, additional radiation is often necessary, and if scans show suspicious internal mammary nodes, radiation should be targeted there too. Care coordination with radiation and medical oncologists is crucial in managing these complex cases.

What else can Breast Lymphatics be?

When investigating swelling in the armpit’s lymph nodes or those above the collarbone, doctors consider several possibilities. These swollen nodes could be due to an infection, but they might also indicate different types of cancer that aren’t related to breast cancer. These cancers could include lymphoma, tumors in the head and neck, skin cancer known as melanoma, or lung cancer.

Surgical Treatment of Breast Lymphatics

Early research on breast cancer testing confirmed that sentinel node biopsy, a procedure that helps doctors detect if cancer has spread, is safe and effective. This method made it possible for doctors to avoid a more invasive surgery called axillary dissection in patients without nodal involvement, which reduced related surgical complications.

Over time, the importance of detecting a positive sentinel node, meaning the cancer has spread, continues to be studied.

The ACOSOG Z0011 trial was a breakthrough study for managing sentinel nodes in patients whose axilla (the area under the arm where the lymph nodes are located) showed no signs of cancer. This study advised that, in cases where only 1 or 2 sentinel nodes show signs of cancer, surgeons should avoid doing an axillary dissection if the patient is undergoing breast conservation surgery and postoperative radiation therapy. This advice doesn’t apply to women with larger (T3 or t4) tumors, those who have cancer spreading beyond the lymph node, or those having only partial breast radiation.

Presently, there are trials being conducted for patients who initially showed axillary nodal metastasis (cancer spread to the lymph nodes under the arm) via needle biopsy, but demonstrated complete imaging response (or healing) of the axilla after undergoing chemotherapy. In one trial, Alliance A11202, patients who showed signs of cancer in the nodes before chemotherapy, will undergo sentinel node biopsy during surgery. If the biopsy is negative, no more surgery is needed. If the biopsy is positive, these patients will be divided into two groups: one will receive chest wall/nodal radiation with additional ALND (axillary lymph node dissection) and the other group without further ALND. The NSABP B51-RTOG 1304 (NRG 9353) schema is a similar trial involving patients with documented nodal disease, who will also be divided into two groups to receive node biopsy or ALND at the time of surgery, and then randomized with or without nodal radiation.

What to expect with Breast Lymphatics

When invasive ductal carcinoma, a type of breast cancer, invades the lymphatic system, it doubles the risk of the cancer returning after the patient undergoes breast-conserving surgery. Although the usual recurrence rate ranges from 0.5% to 1%, having affected nodes in the internal mammary area is linked with a poorer outlook. In these cases, the ten-year survival rate falls between 37% to 62%.

Inflammatory breast cancer, which is a highly aggressive form of the disease, makes up 1% to 5% of all breast cancer cases. This form of cancer progresses rapidly, developing in just weeks to a few months. However, when it is treated with a mix of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, around 50% of patients remain cancer-free at the five-year mark.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Breast Lymphatics

One typical side effect of breast cancer treatment is lymphedema. This problem arises when the lymph, a liquid that flows through your body to combat illness, cannot properly leave the lymph nodes. This often occurs when lymphatic passages in the upper arm are damaged during surgery or radiation. About 5% of patients who have had sentinel lymph node biopsy, and 16% of patients who have had axillary lymph node dissection develop lymphedema within five years.

There are four stages of lymphedema:

- Stage 0: This is not physically noticeable yet due to being subclinical.

- Stage 1: Swelling that decreases with arm lifting.

- Stage 2: Constant swelling associated with hardened tissue or fibrosis.

- Stage 3: Fibrosis with fatty deposits and warts, a condition known as elephantiasis.

It is typically evaluated by comparing the circumference of both arms, but newer methods, including bioimpedance, are also used. Managing this condition often requires consultation with a lymphedema specialist to learn preventive measures and treatment strategies.

In severe cases where the conventional treatments are ineffective and the patient continues to experience recurring lymphangitis (infection of the lymph vessels), unmanageable pain or restricted limb function, surgical measures may be contemplated. These may include lymph node transfer or connection of lymphatic and venous systems, but these procedures are performed only in specialized centers.

Nerve injury is another possible side effect of axillary surgery. This includes damage to the long thoracic nerve (which can result in the shoulder blade sticking out), the thoracodorsal nerve, and the intercostobrachial nerve. It’s crucial to take precautions during surgery to preserve these nerves, including careful use of paralytic agents during anesthesia and proper identification of anatomy.

Recovery from Breast Lymphatics

If patients have had surgery to remove lymph nodes or radiation treatment, it’s helpful to see a lymphedema specialist. These experts can give the right exercises, compression tools, and education to either stop lymphedema from happening or manage it if it does.

Preventing Breast Lymphatics

It’s crucial that patients feel comfortable discussing their fears and questions about breast cancer with their healthcare professionals. Sometimes, cultural, social, or economic factors might make it more challenging for some people to seek breast examinations and screenings. Before any procedure is done on the breast or underarm areas, it’s important that the risk of lymphedema – a condition where extra lymph fluid builds up and causes swelling – is included in the discussion and consent process. Patients should also be educated on how to prevent and manage lymphedema.