What is Pneumonia Pathology?

Pneumonia is an infection in the lungs. But it’s important to recognize that pneumonia isn’t just one disease. Actually, it’s a name used for a group of conditions caused by different types of germs, each resulting in various symptoms and after-effects.

Pneumonia has been grouped in different ways, such as by what causes it, where the patient got it, and which part of the lungs it affects. This introduction will take you through the types of pneumonia as classified by the American Thoracic Society.

Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) is a type of pneumonia you catch while not in a healthcare facility.

Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP) is a type of pneumonia you get after being in a hospital for more than 48 hours. HAP doesn’t include pneumonia that was developing at the time of admission. It’s important to note that now, pneumonia caught in assisted-living facilities, rehabilitation places, and other health care settings are now also considered community-acquired pneumonia.

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP) is pneumonia that a person gets more than 48 hours after having a tube put into their windpipe (endotracheal intubation).

These categories have helped us understand the usual germs responsible for each type of pneumonia. And this understanding has aided in forming treatment plans that work well in both hospital and non-hospital settings.

Depending on which part of the lungs the infection affects, pneumonia has also been studied as:

* Focal non-segmental or lobar pneumonia: This type affects a single lobe of the lung.

* Multifocal bronchopneumonia or lobular pneumonia

* Focal or diffuse interstitial pneumonia.

What Causes Pneumonia Pathology?

Figuring out the exact cause of pneumonia is important for proper treatment and recording disease patterns. However, in real-world medical settings, it happens less often than we would like. One study showed that doctors were only able to find one cause for pneumonia in fewer than 10% of patients who came to the emergency room. But we can still get a sense of the usual culprits.

Pneumonia caught outside of a healthcare setting, known as Community-Acquired Pneumonia, can be down to viruses, bacteria, or fungus. Bacterial pneumonia is usually subdivided into “typical” and “atypical”. The “typical” bacteria commonly include Pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Group A Streptococcus, among others. “Atypical” bacteria, which are less easy to grow in lab cultures, include Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and others.

When it comes to viruses causing pneumonia, it’s not always clear if they’re the primary cause or if they make it easier for bacterial infections to take hold. Some of the most commonly found viruses include the flu virus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, and adenoviruses.

Fungal pneumonia often affects people with weakened immune systems, like those with HIV or organ transplant recipients. However, healthy people can also develop fungal pneumonia, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and worse health outcomes. The most common types in North America are Histoplasma, Blastomyces, and Coccidioides.

If pneumonia is caught in the hospital or when using a ventilator, there can be overlap in the cause. This often includes gram-negative bacteria like Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas Aerugenosa, Acinetobacter, and Enterobacter, as well as gram-positive bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus. In severe cases, the disease can also be due to viruses and fungi, especially in patients who are very sick or have weakened immune systems.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Pneumonia Pathology

Pneumonia is a widespread illness that tremendously impacts all communities. According to a study by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), pneumonia is the eighth leading cause of deaths in America and the seventh in Canada. These rankings consider differences in gender and age.

In a large study on a population of 587,499 adults over two years (2014-2016) in Louisville, the yearly rate adjusted for age showed there were 649 hospitalizations due to pneumonia per 100,000 adults. This number translates to approximately 1,591,825 adults hospitalized with pneumonia annually in the United States. Furthermore, the study found a 6.5% mortality rate during hospitalization, equating to roughly 102,821 deaths per year in the United States. After 30 days, the death rate increased to 13%, moving up to 23.4% in 6 months, and eventually rising to 30.6% after a year. It’s worth noting that these rates were higher in economically challenged areas and predominantly Hispanic or African-American populations.

The Community-Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) database, organized around incidents in 16 countries located in the United States/Canada, Europe, and Latin America, found death rates of 7.3%, 9.1%, and 13.3% in these regions, respectively.

Information about the occurrence and frequency of HAP and VAP is somewhat limited, primarily due to other health conditions that patients might have. Some estimates suggest that the occurrence of VAP is around 2 to 16 incidents per 1000 days on a ventilator, with a death rate linked to the disease being 3% to 17%. A significant challenge in treating HAP and VAP lies in the high resistance of the associated bacteria to multiple drugs. Factors that can increase the risk of drug resistance include other health conditions of the patient, recent use of antibiotics, functional state, and illness severity.

- Pneumonia is common and is the eighth leading cause of death in the United States and seventh in Canada.

- In a study conducted on adults in Louisville, around 649 per 100,000 were hospitalized annually due to pneumonia, equating to around 1,591,825 hospitalizations across the US each year.

- The death rate during hospitalization was 6.5%, increasing to 13.0% after 30 days, 23.4% after 6 months, and 30.6% after a year.

- These rates were higher in lower-income areas and among Hispanic or African-American populations.

- Death rates from pneumonia in the United States/Canada, Europe, and Latin America were 7.3%, 9.1%, and 13.3% respectively.

- Data about hospital and ventilator-associated pneumonia (HAP and VAP) is limited, but estimates suggest that the occurrence of VAP is 2 to 16 incidents per 1000 ventilator days, with an attributable death rate of 3% to 17%.

- Treating HAP and VAP is challenging due to the high resistance of the associated bacteria to multiple drugs. Risk factors for drug resistance include the patient’s other health conditions, recent use of antibiotics, functional state, and severity of illness.

Signs and Symptoms of Pneumonia Pathology

Pneumonia is an infection that causes inflammation in the lungs. Common complaints among patients may include general symptoms such as fever and chills, fatigue, loss of appetite, and muscle pain. These are more often seen in cases of viral pneumonia as compared to bacterial pneumonia. In some cases, patients may also experience confusion, stomach ache, chest pain, and other body-wide symptoms. Pneumonia can cause a cough which may or may not produce sputum, a mixture of saliva and mucus. Bacterial pneumonia often leads to the production of pus-filled or occasionally blood-streaked sputum, while viral pneumonia generally results in watery or sometimes a mucus and pus mix in the sputum.

Pneumonia may also cause discomfort in the chest, inclusive of pleuritic chest pain – a sharp, stabbing pain that worsens with deep breathing or coughing. Some individuals may also experience difficulty in breathing and a general heavy feeling in the chest.

When a health professional examines a patient, they may notice:

- Fast breathing (Tachypnea)

- Rapid heart rate (Tachycardia)

- Fever with or without chills

- Diminished or bronchial (lower pitch, harsh or hoarse) breath sounds

- Signs of lung consolidation such as Egophony (a change in voice sound that’s audible when listening to the chest with a stethoscope) and tactile fremitus (vibrations felt on touching the chest)

- Crackling sounds when listening to affected areas of the lung

- A dull sound when tapping (percussing) the chest

Testing for Pneumonia Pathology

If your doctor suspects that you have Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) or Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP), they will take a few steps to confirm this. First, they will ask about your symptoms and medical history and then perform a physical examination.

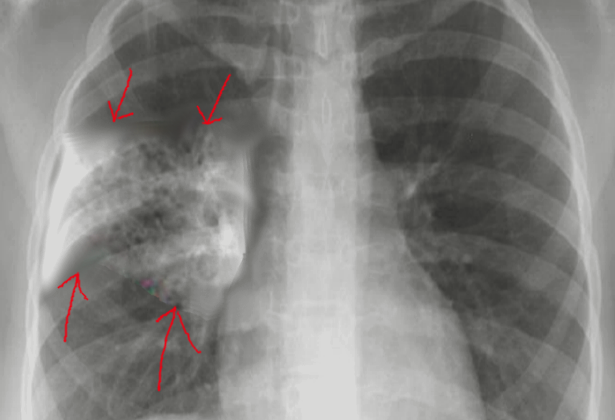

They may also arrange for you to have a chest X-ray. According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society guidelines, this is the best method to diagnose pneumonia when combined with the results of your physical exam. The X-ray may show different signs, such as spots in your lung(s), that suggest more severe disease.

They may also run a series of lab tests, such as blood and phlegm cultures to identify pathogens–the germs causing the infection. Two particular tests, the procalcitonin and the C-reactive protein tests, can help differentiate between viral and bacterial causes when the illness isn’t clear from other evidence. Notably, your doctor might give you antibiotics as a precaution in cases where pneumonia is highly suspected, and it might not be necessary to run all these tests.

The evaluation process is a little bit different if your doctor suspects Ventilator-associated Pneumonia (VAP) and it’s a little bit more involved. To diagnose VAP, radiological (X-ray or CT scan) and microbiological (sample collection and testing) evidence is needed before starting antibiotic treatment. VAP should be suspected if a patient on a ventilator experiences new difficulty breathing, a fall in oxygen levels, fever, chills or new spots appear in the lungs on an imaging test. Once the diagnosis of VAP is confirmed, appropriate antibiotic therapy can be started.

Treatment Options for Pneumonia Pathology

When someone is diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), which is a type of pneumonia caught from a non-healthcare environment, the first step is to determine how serious their condition is and to decide on the best course of treatment. This often involves deciding whether the patient can be treated at home, in a hospital ward, or if they need to be cared for in an intensive care unit (ICU). A scoring system known as the “CURB-65” scale is often used to help make this decision. This scale considers five factors: confusion level, uremia (elevated waste products in the blood), respiratory rate, blood pressure, and age. Each positive criterion gives one point.

Patients who score 0 to 1 on this scale are usually managed at home. Their treatment often involves the use of antibiotics, with the type of antibiotic chosen based on the presence of any other health conditions. Patients with a score of 2 to 3 will typically be admitted to a general medicine ward at a hospital. Here, the first line of treatment usually involves a choice between two types of antibiotics. Patients who score 4 or more are cared for in an ICU, where the treatment consists of a combination of particular antibiotics.

With regards to the management of ventilator-assisted pneumonia (VAP) and hospital-acquired pneumonia (HaP), both caught from healthcare facilities, treatment usually follows guidelines provided by the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America (ATS/IDSA). Treatment of these types of pneumonia is often more complex and longer-lasting than the treatment of CAP. It usually involves the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, capable of fighting off a wide range of bacteria.

Successful treatment requires early identification of signs of pneumonia and a detailed evaluation, before starting empiric therapy. This therapy is guided by knowledge of which bacteria are most commonly resistant to antibiotics in the specific region, as well as the patient’s risk factors for resistant infections. Regimens for these types of pneumonia generally cover common bacteria known to cause these conditions. For patients without risk factors for the development of multi-drug resistant infections, a specific set of antibiotics is typically used. But for those with these risk factors, a different set of antibiotics is employed.

What else can Pneumonia Pathology be?

When a doctor is trying to diagnose pneumonia, they also need to consider other conditions that could cause similar symptoms. Conditions that could be mistaken for pneumonia include:

- Asthma

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Lung edema (fluid in the lungs)

- Lung cancer

- Non-infective lung diseases

- Pleuritis (inflammation of the lining of the lungs)

- Pulmonary embolism (blood clot in the lung)

- Aspiration of a foreign body (inhaling a foreign object)

- Bronchiectasis (enlarged airways)

- Bronchiolitis (inflammation of the small airways)

If it’s hard to determine the exact condition, doctors might use certain medical tests. These tests could check for things like C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, procalcitonin levels, white blood cell count, and body temperature to better establish a diagnosis.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Pneumonia Pathology

If pneumonia isn’t treated properly, it can lead to several serious complications. These include respiratory failure, where your body can’t get enough oxygen; sepsis, a dangerous infection that spreads throughout your body; and metastatic infections, which are infections that spread from the original site to other parts of your body. Other complications can include empyema, a buildup of pus in the lungs; lung abscess, a pocket of pus inside the lung; and multi-organ dysfunction, when several of your body’s organs aren’t working correctly.

Common Complications:

- Respiratory failure

- Sepsis

- Metastatic infections

- Empyema

- Lung abscess

- Multi-organ dysfunction