What is Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia?

Pneumonia is an infection that occurs in the lower part of the respiratory system, specifically affecting the lungs. It can be caused by various organisms like viruses, fungi, and bacteria. The severity of pneumonia varies greatly – it can be mild or extremely serious, leading to complications like septic shock, extreme breathing difficulties, or even death. A mild case can be treated with antibiotics at home, but severe cases may get worse without immediate medical attention.

Pneumonia affects everyone, regardless of age, and leads to over 2 million emergency room visits every year. It’s a leading cause of death in both adults and children. Certain types of “atypical” micro-organisms are known to cause more severe disease in children and teenagers. These atypical organisms are hard to identify in lab tests, and their symptoms can develop slowly and get worse over time.

Additionally, a bacteria called streptococcus pneumonia is responsible for about 70% of pneumonia cases, while the remaining 30% are caused by these atypical organisms.

What Causes Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia?

Pneumonia happens when a large amount of harmful organisms get past the body’s natural defenses and make their way into the lungs. There are a few ways this can happen – for example, by breathing in a lot of these harmful organisms, being exposed to increasingly harmful organisms, choking on something, or having a weak immune system.

There are different ways to classify or group pneumonia, depending on where you catch it (like in the community or in a hospital), or what’s causing it (like a virus, bacteria, or atypical bacteria). Atypical pneumonia can be caught from a range of sources and can be caused by a number of paths, though the most common one is a type of bacteria called Mycoplasma pneumonia.

Mycoplasma pneumonia is responsible for most atypical respiratory infections. However, only about 10% of individuals who encounter mycoplasma will actually get pneumonia. Younger individuals typically catch it in closed spaces, like schools and homes, but anyone can get it. The bacteria can be passed from person to person, and symptoms can show up anywhere between 4 to 20 days after exposure. These symptoms can include tiredness, cough, muscle pain, and a sore throat. The cough typically gets worse at night. In most cases, the infection isn’t severe and gets better on its own. But for some people, it can cause additional symptoms like skin rashes, meningitis, Guillain Barre Syndrome, and cerebral ataxia. People with preexisting lung disease may also develop serious complications like empyema, pneumothorax, or even respiratory distress syndrome.

Another common cause of lung infection is a bacteria called Chlamydia pneumoniae. This bacterium can be breathed in from tiny, contaminated water droplets in the air. The symptoms are usually mild and take a long time to show up. It’s most common in elderly people and the symptoms can include a sore throat, cough, and a headache that can last for several weeks or even months.

A more harmful type of pneumonia is caused by a bacteria called Legionella pneumoniae. This bacteria thrives in water systems like humidifiers, whirlpool, respiratory therapy equipment, water faucets, and air conditioners. Places where water is stagnant allows the bacteria to multiply. People at risk of catching this type of pneumonia might have diabetes, cancer, kidney or liver disease, and they might have recently done plumbing work at home. Symptoms include change in mental state, cough, fever, and breathing problems. Patients often need help with breathing and may need to be put on a ventilator. This type of pneumonia is severe and should be treated quickly to avoid serious illness.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia

It is believed that between 7% and 20% of pneumonia acquired outside of healthcare facilities is caused by atypical bacteria. These bacteria are hard to detect and grow in a lab due to their ability to live inside the cells. We are not certain about the exact number of cases. But, because the treatment is usually the same, knowing the exact bacteria causing the infection is often not important. This type of pneumonia tends to affect younger people more, with age being the major factor to predict it in adults.

- 7% to 20% of pneumonia caught in community settings is caused by atypical bacteria.

- These bacteria live inside cells, making them hard to see or grow in lab conditions.

- The exact number of these cases is not known.

- Knowing the specific bacteria often isn’t needed as the treatment is usually the same.

- Younger people are more prone to this type of pneumonia.

- Age is the only reliable predictor for this condition in adults.

Signs and Symptoms of Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia

Patients may show subtle signs of illness for an extended period. Traditional understanding suggests that individuals with atypical infections might experience slow onset of symptoms, such as a sore throat, headache, dry cough, and slight fevers. They often have no clear lung infection signs when examined or imaged, unlike those with pneumonia caused by pneumococcus bacteria.

To top it off, they frequently show symptoms outside the heart and lungs. For instance, infections caused by mycoplasma are often connected with skin rashes and painful blisters in the ear, while Legionella – a type of bacteria – is typically linked with digestive issues and issues with the balance of minerals in the body.

Testing for Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia

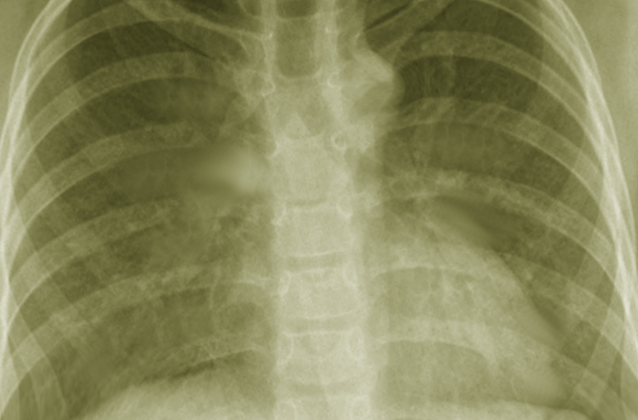

If a patient doesn’t seem seriously ill, particularly when seen by a doctor outside the hospital, being highly suspicious of a certain condition could be enough to start treatment right away. However, for individuals who seem very unwell, or where it’s unclear what’s wrong, a chest x-ray is the usual go-to test. Doctors might also run different tests to get more information, guide the treatment plan, and better understand the patient’s risk.

Blood tests are usually a part of the decision-making process, but they don’t solely determine the course of action. Sometimes, doctors might want to check the patient’s white blood cell count because high levels can suggest infection. They might also want to run a pro-calcitonin test which can help them figure out if the infection is caused by a virus or bacteria.

Patients who are hospitalized will also get tests for specific germs in their urine, and they might have a viral PCR test which helps to identify certain types of infections. If a patient is very unwell, it’s also critical to test their blood and, if possible, their sputum (coughed-up mucus), to guide their treatment and help reduce the use of unnecessary antibiotics.

Imaging can highlight changes in the lungs characteristic of atypical pneumonia, like scattered areas of lung inflammation, sometimes on both sides, and intricate patterns. It’s less usual to see complete areas of lung inflammation or complex lung abnormalities like a pus-filled lung pocket or a severe lung condition called ARDS with this type of pneumonia.

Treatment Options for Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia

Atypical organisms like M. pneumoniae, the most common of its kind, do not have cell walls. For this reason, antibiotics known as beta-lactam are not the best choice. While there’s no need to take blood samples for culture before starting treatment, it is advisable to collect and test patient’s sputum. Antibiotics should be introduced within four hours for patients in the hospital.

The go-to treatment usually involves the use of antibiotics from the macrolide family, but there’s growing resistance to these drugs. Azithromycin is often used due to its availability in both IV and oral forms, and patients are likely to follow through with their treatment as it only lasts 5 days. For outpatients, fluoroquinolone and tetracycline are other options. They are often the choice for older patients or those appearing more ill, mainly when more infectious bacteria are suspected. If the patient has been admitted to the hospital with a presumption of community-acquired pneumonia, treatment is often widened to include a beta-lactam drug like ceftriaxone with azithromycin.

Doctors often assess the severity of pneumonia to decide if patients should be treated in the hospital or at home. For instance, patients looking well who are suspected of having the atypical organism can receive antibiotics and other necessary care at home.

Some treatments fail due to resistance to antibiotics, a patient not following treatment routines, inability to take oral medication, or wrong diagnosis. Notably, almost half to 60% of patients may have fluid build-up in their chest, visible in x-ray scans. If not resolved, this often leads to an infection. It’s generally recommended to drain out the fluid if the pH level is below 7.2.

For children under five, atypical pathogens aren’t often the cause. But if suspected, amoxicillin is administered for 7-14 days. For children aged over five, antibiotics from the macrolide family are recommended. Often, children with atypical pneumonia need hospitalization and may require injected medication and extra oxygen.

Older patients with atypical pneumonia can show altered mental signs and have a higher risk of aspiration due to comorbidity. These patients should also be treated for anaerobic infections. An individual may need to be admitted to the hospital for varying reasons, such as breathing rate of more than 30 bpm, oxygen saturation less than 90% on room air, low blood pressure, severe lung disease, heart failure, diabetes, or changes in mental status.

What else can Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia be?

When trying to diagnose pneumonia, doctors need to check for conditions related to the heart, respiratory system, and musculoskeletal system. Conditions related to the heart that can show symptoms similar to a viral infection, such as pericarditis (inflammation of the sac surrounding the heart) and myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle), need to be considered.

The respiratory system is divided into the upper and lower parts. In the upper part, a doctor will need to check conditions like pharyngitis (inflamed throat), sinusitis (sinus infection), or more urgent conditions like epiglottitis (inflamed ‘lid’ over the windpipe) and retropharyngeal abscess (an abscess behind the throat).

For the lower part of the respiratory system, an X-ray of the chest can help distinguish bronchitis (inflamed bronchial tubes) or bronchiolitis (inflamation of small airways) from pneumonia (lung infection). The diagnosis can get complicated if the X-ray shows something unusual. These unusual results could mean that patient has atypical/viral/bacterial pneumonia, polymicrobial aspiration (infections caused by multiple types of bacteria), or chemical pneumonitis (inflammation caused by inhaling substances). Asthma and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) could also mimic these results, yet they aren’t caused by infections.

Lastly, doctors need to consider conditions related to the musculoskeletal system like costochondritis (pain caused by inflammation around the ribs) and rib dysfunction. Still, these conditions often don’t come with general symptoms that most diseases show.

What to expect with Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia

Most patients suspected of having an atypical infection can be effectively treated as outpatients. This typically leads to full recovery and a low risk of complications or death. If they don’t have serious other health conditions and their vital signs are normal, their treatment process is usually uncomplicated.

However, not all cases go as expected. Hence, it’s important to regularly check in with the doctor and follow their instructions closely to keep track of how the disease might be progressing.

Preventing Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia

Everyone is encouraged to get the yearly flu vaccine. It’s also recommended that older adults receive the pneumonia vaccine.