What is Community-Acquired Pneumonia?

Community-acquired pneumonia, which is when someone gets pneumonia outside of a hospital or healthcare setting, is a top reason for people to be hospitalized. It’s also a common cause of death and leads to substantial healthcare expenses. The severity of this illness can vary a great deal. It can be a mild sickness that can be taken care of at home, or it can be severe enough to require treatment in an intensive care unit at a hospital. Because of this range in severity, it’s essential to diagnose it early and determine the right level of care. This can significantly improve the patient’s outcome.

What Causes Community-Acquired Pneumonia?

Community-acquired pneumonia, which is a type of pneumonia you can get when you’re not in a hospital, can be caused by many different kinds of germs, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. There are several types of common bacteria that often cause this illness:

– Gram-positive bacteria, like Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococci, and other types of streptococci

– Gram-negative bacteria, such as Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Enterobacteriaceae

– Atypical bacteria, like Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Chlamydia psittaci

Viruses can also cause pneumonia. Some of the most common ones are rhinovirus, influenza, the virus that causes COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2), and other viruses that affect the respiratory system like parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and human metapneumovirus. Modern methods of testing have made it easier to identify these viruses as causes of pneumonia.

Globally, S pneumoniae and H influenzae are the main bacterial causes of acute pneumonia. A recent study in the United States found that the most common causes of pneumonia were the human rhinovirus, influenza virus, and S pneumoniae.

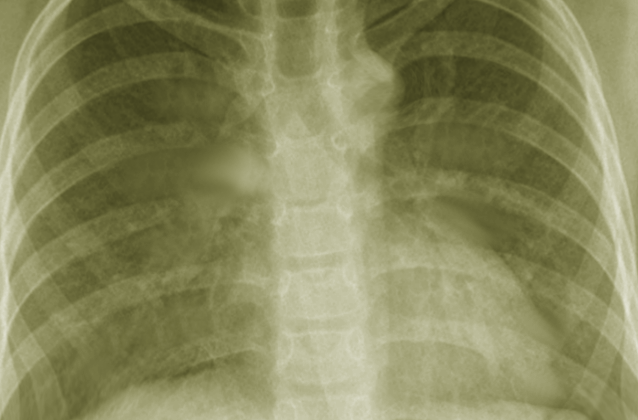

right lung is an abscess. The diffuse ground glass infiltrates seen in both

lungs represent pneumonia.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia is a condition that varies significantly around the world. Its incidence can range from as low as 1.5 to as high as 14 cases per 1,000 people each year. Factors such as the location, season and the characteristics of the population can influence these rates. In the United States, the yearly incidence is comparatively higher, with approximately 24.8 cases per 10,000 adults, and this rate increases with age. Pneumonia is the eighth most common cause of death, making it the leading infectious cause. Patients admitted to intensive care for severe pneumonia can have a mortality rate as high as 23%.

Everyone with a pre-existing illness is at risk for pneumonia, but there are some specific risk factors associated with certain types of pneumonia. For example, pneumonia caused by drug-resistant pneumococci is more likely to occur in:

- People older than 65

- Children in daycare centers

- Anyone who has taken beta-lactam antibiotics in the last 90 days

- Individuals with alcohol use disorder, chronic health problems, or a weakened immune system

On the other hand, pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas is more likely in:

- People with bronchiectasis

- Individuals dealing with malnutrition

- Those undergoing corticosteroid therapy

- Anyone taking antibiotics for more than 7 days in the previous month

Geographic areas can also give clues about the cause of pneumonia:

- The Southwestern US is known for coccidioidomycosis

- The states of the Ohio River valley are known for blastomycosis or histoplasmosis

- Chlamydia psittaci can result from exposure to birds

- In the Northeast US places like Martha’s Vineyard and Cape Cod, contact with flea-infested or infected rodents or rabbits during outside activities such as lawn mowing can lead to tularemia pneumonia

Signs and Symptoms of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an infection that can cause a variety of symptoms. These often include:

- Fever

- Chills

- Cough with sputum (mucus)

- Difficulty breathing

- Chest pain that worsens when coughing or breathing

- Weight loss

However, people who have problems with alcohol use or weakened immune systems might not have a fever or typical symptoms. Instead, they might feel weak, tired, confused, or have upper stomach issues. Some additional symptoms can give clues about the cause of pneumonia. For example, symptoms like diarrhea, headache, and confusion could point to a Legionella infection; ear infection, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or anemia with jaundice could suggest a Mycoplasma infection. Pneumonia can also worsen symptoms in people with chronic illnesses like congestive heart failure, which could delay diagnosis and treatment.

Testing for Community-Acquired Pneumonia

If there’s a suspicion of pneumonia, the first steps often include imaging tests and blood work. A chest x-ray is useful to check for any irregularities such as a buildup of fluid or other signs common in pneumonia cases. As for blood tests, these can help identify signs of inflammation and gauge how bad the pneumonia is. They may complete a blood count, test for electrolytes, and perform liver and kidney function tests.

If it’s winter, doctors might also test for the flu because influenza and pneumonia share many symptoms. Similarly, tests for other respiratory viruses might be considered, using nasal and throat swabs if possible.

Doctors also use tools to assess how severe a patient’s pneumonia might be. CURB 65, which looks at confusion levels, urea measurements, respiratory rate, and blood pressure, and the Pneumonia Severity Index, are two examples. These can guide doctors as to where treatment should take place (like in a hospital or at home), but aren’t always 100% accurate. They still need to exercise professional judgment based on the patient’s overall condition.

If a patient has been admitted to the hospital, doctors may take blood and sputum cultures. This should ideally happen before starting antibiotic treatment, but it shouldn’t delay the overall treatment process. If these cultures don’t show any signs of infection, urine tests may be done to check for specific types of bacteria that could help diagnose pneumonia. If the patient has other health conditions, like congestive heart failure, doctors might use serum procalcitonin levels as an indicator to start and govern antimicrobial therapy. Depending on indicators in the patient’s environment, doctors might also check for diseases like tularemia, endemic mycoses, or C psittaci.

Treatment Options for Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Outpatient treatment for certain illnesses often includes a one-drug therapy involving a macrolide (such as erythromycin, azithromycin, or clarithromycin) or doxycycline. However, if other illnesses are present, like heart disease, lung disease, liver disease, diabetes, or HIV, then a combination of medicines including a respiratory fluoroquinolone (like high-dose levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin) and a beta-lactam (like high dose amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefuroxime, cefpodoxime), might be prescribed.

For patients with a higher CURB 65 score, indicative of the potential need for hospitalization, a respiratory fluoroquinolone or a combination treatment with a beta-lactam (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ampicillin-sulbactam, or ertapenem) may be recommended.

Patients showing three or more signs of early stage deterioration, such as a high respiratory rate, low blood oxygen level, presence of multilobar infiltrates, sudden change in mental state, low platelet count, and low body temperature, should be considered for intensive care. A combination of a beta-lactam and either a macrolide or fluoroquinolone is usually recommended. Single-drug therapy is not recommended in this scenario.

If the bacteria Pseudomonas is suspected, additional medicines are recommended alongside either an antipseudomonal fluoroquinolone or a combination of aminoglycoside and azithromycin. If there is a risk of infection from community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus, treatment with Vancomycin or Linezolid should be added.

The treatment usually lasts for 5 to 7 days if the patient shows positive signs of recovery including absence of fever, normal breathing and heart rate, and stable blood pressure. However, longer treatment of up to 21 days might be necessary for specific bacterial pathogens or complications such as lung abscess or necrotizing pneumonia. In such severe cases, a chest tube might be required to be placed to drain the infected fluid. Certain illnesses like tularemia pneumonia or psittacosis may require a 14-day course of macrolide or doxycycline.

If a patient tests positive for influenza virus within 48 hours of symptom onset, it’s generally recommended to have a 5-day therapy with oseltamivir. However, for any hospitalized influenza patients, treatment with oseltamivir is recommended irrespective of the time elapsed since the onset of illness.

IV glucocorticoids can be considered as an added therapy in critically ill patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia without risk factors for adverse outcomes from using steroids such as influenza infection. These are associated with reductions in short-term fatality rate and duration of intensive care stay.

What else can Community-Acquired Pneumonia be?

When diagnosing community-acquired pneumonia, doctors need to consider other illnesses that have similar symptoms. These could include:

- Severe bronchitis

- Worsening chronic bronchitis

- Lung injury caused by inhaling foreign materials

- Heart failure leading to fluid in the lungs

- Lung scarring

- Heart attack

- Lupus affecting the lungs

- Allergic lung reaction to certain medications (nitrofurantoin, daptomycin)

- Lung problems caused by certain medicines (bleomycin)

- Sarcoidosis, a disease with unknown causes that causes tiny lumps of cells in various organs

- Unexplained lung disease causing inflammation and scarring in the lungs

- Blood clot in the lung

- Cutting off blood flow to the lung

- Lung cancer

- A form of vasculitis called Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Lymphoma, a type of cancer that starts in cells that are part of the body’s immune system

- Inflammation of the windpipe and larger airways in the lungs

- Disease caused by radiation treatment to the lung

The physician must be thorough when considering all these possibilities, conduct the necessary investigations, and interpret the results accurately to determine the best treatment method.