What is Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections?

Nontuberculous mycobacteria, or NTM, are common in our environment. They can cause infections in everyone, irrespective of their immune system’s strength. In recent years, the existence of these infections has been on the rise globally, turning into a significant public health issue.

Consequently, different international health organizations like the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the British Thoracic Society started developing ways to diagnose and treat lung infections caused by NTM. In 2020, these two societies, along with the European Respiratory Society (ERS), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID), worked together to create shared guidelines.

As we continue to learn more about NTM lung infections, notably due to advances in molecular microbiology, these guidelines keep getting updated. Recognizing NTM as a cause of complex infections and these scientific advancements have resulted in making NTM diagnosis more accurate and quicker than before.

This simplified summary brings the critical aspects of NTM lung infections, including the root of the spread, symptoms, diagnostic processes, and how to manage them. It emphasizes the importance of a team effort from medical experts to provide better care for those infected with NTM lung infections.

What Causes Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections?

Since the discovery of the tuberculosis-causing bacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) in 1882 by Robert Koch, there’s been a substantial increase in our understanding of other related bacteria, often referred to as nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). The first among these, Mycobacterium avium, was identified in birds, separate from tuberculosis, by 1890. It was only by the mid-20th century that these NTM were recognized as causing diseases in humans. Today, over 150 types of NTM have been identified.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and NTM are all categorized under the same genus – Mycobacterium. These bacteria are typically slender, weakly stainable by the Gram stain method but stain well with acid-fast staining due to their mycolic acid-rich cell walls. There’s a lot of variation in their length and thickness. You can also identify them based on their color change in the presence or absence of light (a property known as being ‘photochromogenic’ or ‘scotochromogenic’) and their growth characteristics.

There are also other ways to tell these bacteria apart, like their growth rates, similarities or differences in their colonies, their biochemical properties, and chromatography, a method used to separate mixtures. Some NTM species grow quickly (within 7 days) in liquid cultures, while others are slow grower, taking more than two weeks to grow. However, these older identification methods have been largely replaced by more modern and precise molecular and genomic methods.

This shift to newer methods has allowed for the identification of even more NTM species and for differentiation based on their genomic differences. In places like the US, Japan, and French Guiana, among the most commonly identified NTM species causing lung diseases include bacteria from the Mycobacterium avium complex, Mycobacterium gordonae, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium fortuitum, and Mycobacterium abscessus.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

Understanding how widespread NTM lung infections are can be complicated. This is due to several reasons such as not reporting these types of infections to local health departments in several countries, the challenge of distinguishing whether a person has the infection or the disease, the difficulty of diagnosing the infection in places with limited facilities, and because keeping track of patients’ treatment can be challenging.

Research indicates that people of Asian and Pacific Islander descent might be more likely to develop NTM lung disease. Several factors could contribute to this increased risk, including a higher incidence of M tuberculosis in these populations, a history of tuberculosis, advanced age, a weakened immune system, and the use of corticosteroids.

In the 1980s, US laboratories reported an estimated 1 to 2 cases of NTM infection per 100,000 people. The annual prevalence increased among both men and women in Florida; in New York, only women showed an increase. However, California did not observe any significant increase. For older individuals, those aged 65 and above, the prevalence of NTM lung diseases increased from 20 per 100,000 in 1997 to 47 per 100,000 in 2007.

Reports from around the world have shown an increase in the occurrence of NTM lung infections since the 1950s. This includes Slovakia, the UK, Ireland, Australia, Japan, South Korea, and the US. In Queensland, Australia the rates increased from 2.2 per 100,000 in 1999 to 3.2 per 100,000 in 2005.

Even though NTM lung disease has been increasing over the years, both in the US and globally, it’s not completely understood why this is. Increased awareness among doctors and an aging population have been suggested as potential reasons. Other possibilities include increased exposure to plumbing, indoor swimming pools, high rainfall events, and soil disruption. Hot tubs have also been connected to cases of MAC.

New technology such as high-resolution chest CT scans, improved diagnosis methods, and increased chest screening are all factors that can help detect such cases earlier and more accurately.

Signs and Symptoms of Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

Pulmonary NTM (non-tuberculous mycobacteria) infection is a lung disease which can be challenging to diagnose. Guidelines from the ATS/ERS/IDSA/ESCMID recommend investigating clinical symptoms, looking for signs on chest scans, excluding other possible conditions, and conducting lab tests on sputum samples to confirm a diagnosis. Since the bacteria responsible for this disease grow slowly, they take a long time to impact the lungs causing symptoms, which can result in a delayed diagnosis or even misdiagnosis.

Similarities exist betwixt the symptoms of pulmonary NTM and those of pulmonary tuberculosis (another lung infection). People with NTM symptoms frequently exhibit:

- Cough,

- Shortness of breath,

- Increased sputum (phlegm) production.

Although NTM has fewer lung cavities and infiltrates compared to tuberculosis, NTM tends to be associated with more systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss. The infection often co-exists with bronchiectasis and HIV, causing more spread-out, extrapulmonary disease. Symptoms can range from a few days to a few weeks. Chronic lung infection may also occur, leading to structural changes in the lungs, similar to those seen in lung cancer, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, and fungal lung disease.

The physical examination might reveal different results depending on the individual. Skin lesions could be seen in patients with extrapulmonary disease, which may indicate NTM lymphadenitis. Patients might also have an enlarged liver or a sore abdomen if MAC (a type of NTM infection) has spread extensively. Patients with NTM lung infection might also present with preexisting lung diseases, which could come with its own additional symptoms.

Testing for Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

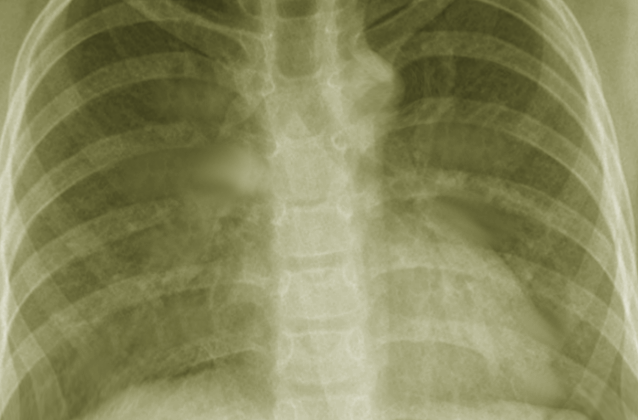

In order to accurately diagnose illnesses that affect the lungs, such as non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infections, doctors rely heavily on radiological imaging, like X-rays or CT scans. Interestingly, NTM infections have unique appearances on these images. Two main types of patterns can be observed: Fibrocavitary and Nodular Bronchiectatic. The Fibrocavitary pattern looks similar to tuberculosis, with cavities and darker spots, typically found in the upper part of the lungs. Conversely, the Nodular Bronchiectatic pattern often presents with bronchiectasis – a dilation or enlargement of the bronchi, mainly located in the middle and lower parts of the lungs, and small nodules visible in imagery. These patterns are most commonly seen among elderly women who do not smoke and have no prior lung conditions. It’s also worth noting that bronchiectasis is present in a significant proportion of patients with NTM lung infection.

Alongside imaging, laboratory tests are also essential in diagnosing NTM. However, this can be challenging because NTM bacteria are found in everyday environments, such as water sources, leading to potential false positives in tests. To counter this, guidelines suggest collecting three early morning sputum (a mixture of saliva and mucus coughed up from the lungs) samples on different days. Various techniques are used for these tests, but they can’t alone distinguish between tuberculosis and NTM. Therefore, additional tests are needed.

One such test is the Nuclei-Acid Amplification (NAA), which is incredibly accurate in identifying different types of mycobacteria. Culture tests, where the bacteria are grown in a controlled environment, are another reliable method. However, these techniques are time-consuming and can be influenced by other variables, such as other microorganisms or previous medication use.

It’s paramount to accurately identify the NTM species because each type requires specific treatment. The most precise method of identification is gene sequencing. Sequencing the 16S rRNA gene allows for the differentiation between different species. This process, however, can be complex and is often conducted in specialised laboratories. Another technique is the matrix-associated laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), which identifies bacteria by comparing specific molecules.

Once the NTM bacteria are identified and cultured, it’s crucial to determine how responsive they are to different drugs, a process known as “drug susceptibility testing.” This is necessary because different NTM organisms display varying resistance patterns to different drugs. However, this testing paired with the laboratory results informs the prescription of the most appropriate drug regimen for each patient.

Treatment Options for Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

When it comes to treating non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) diseases, it’s crucial to take a comprehensive, patient-focused approach. Unlike lung infections caused by tuberculosis, where immediate treatment is critical, NTM lung infections allow some time between diagnosis and the start of treatment. However, starting the treatment as soon as possible can help prevent the disease from progressing.

Treatment of NTM lung infection involves the combined efforts of a healthcare team and open discussion about potential risks and benefits to the patient. Even after treatment has started, patients are closely monitored for the potential side effects of medication and to ensure they are taking their prescribed medication correctly, as most patients require numerous antibiotics to effectively combat the infection. It’s also worth noting that treatment for NTM lung infection can be costly, with lifetime expenses varying from $398 to $70,000, based on 2009 data.

In terms of specific diseases caused by NTM, Mycobacterium avium-intracellular (MAC) disease treatment varies depending on the severity and progression of the disease. Normally, a combination of antibiotics – including macrolides, ethambutol, rifamycin, and possibly aminoglycosides for severe cases – is recommended. Sometimes, more specialized antibiotics could also be needed.

Advanced NTM diseases or those that have been previously treated require a different set of antibiotics, including clarithromycin, rifabutin or rifampin, and ethambutol. For cases that are resistant to treatment, the choice of antibiotics becomes more complicated and may even include an inhaled form of the antibiotic amikacin.

Non-tuberculous mycobacterial antimicrobial therapy aims to achieve culture conversion, which is when the bacteria are no longer detectable in sputum samples for several months. It has been observed that, in NTM pulmonary infection, patients treated longer than 12 months manage to achieve culture conversion within a shorter period and have reduced mortality rates.

Mycobacterium kansasii lung disease is the second most common cause of pulmonary NTM in the US but is relatively treatable. It is typically managed with a combination of antibiotics similar to the treatments for tuberculosis, and these regimens have proven to be quite effective.

The treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus complex lung disease can be more complicated due to the bacteria’s resistance against standard treatments. As a result, the search for a successful treatment continues, with most current strategies relying on extended periods of different types of antibiotics.

Patients should be well informed about the potential side effects, reactions and interactions of the medications used in the treatment of NTM diseases. These may include gastrointestinal symptoms, cardiac irregularities, hearing disturbances, liver injury, discoloration of body fluids, and potential blood-related issues.

Surgical intervention may be considered in some cases, especially when medication hasn’t been effective enough. Surgical treatment can help remove severely damaged parts of the lung and enhance the efficacy of drug treatment. It’s also considered a good option in case of severe symptoms like massive blood coughing. However, careful evaluation is needed before opting for surgery, as it has associated risks and can lead to complications.

What else can Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections be?

If someone has symptoms of NTM (Nontuberculous Mycobacteria) lung infection, it could also mean they have other similar conditions. These conditions can include other lung infections like atypical bacterial infections, chronic lung diseases or even a different type of NTM infection. Doctors need to look at the patient’s risk factors, specific symptoms, and any results from imaging tests, to make the right diagnosis.

Conditions that can look like NTM lung infections include:

- Klebsiella pneumoniae infection

- Staphylococcus aureus infection

- Burkholderia pseudomallei infection

- Fungal lung infections like Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Mucor, Histoplasma, and Coccidioides species, especially if the patient has cavities in the lung

- Small-cell and non-small-cell lung cancers

- Connective tissue disorders like rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Generally, any condition that affects the respiratory system and involves cavities or bronchiectasis in the lungs is a possible diagnosis. These conditions all need to be ruled out by the doctor to ensure the correct treatment is given.

What to expect with Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

NTM lung infection can have a guarded prognosis, particularly if it’s not treated. The chance of overcoming this infection varies and depends on certain factors. For example, based on a South Korean study, for every 183,267 infections, about 86.3% of people were alive after six years, 80.8% after ten years, and 77.1% after fourteen years of receiving treatment. A different study in Croatia found that, given five years, 60% of patients with lung NTM were alive compared to 70% of people without this condition.

People with a weak immune system may find it tougher to recover than those with a strong immune system. In addition to this, if a person with lung NTM has other illnesses, their life expectancy after being diagnosed can be as low as 8.6 years, lower than those who don’t have such illnesses. The diagnosis method can also impact the course of the disease. For instance, patients who found out they had lung NTM through ways other than examining their spit (sputum) had a lower risk of their condition getting worse over the next five years compared to those diagnosed through sputum culture.

Another important factor is the type of NTM lung infection a person has. Some studies have found that patients with an infection called MAC have a better chance of recovery compared to patients with other NTM infections. On the other hand, patients with a type of infection known as M abscessus have a higher death rate in comparison to patients with other NTM lung infections.

Several risk factors can influence the risk of death for patients with NTM lung infection. These include being older (65 years and above), being male, having a low body mass index (under 18.5 kg per square meter), having chronic heart or liver diseases, having another lung disease known as chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, and having lung damage at the time of diagnosis.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

Pulmonary NTM (Nontuberculous Mycobacteria) infections can affect people who have both strong and weak immune systems in a variety of ways. Some people who have these types of infections experience no symptoms at all, others may have minor symptoms, and some can experience severe issues such as the creation of holes in the lungs, or entire body illness. In a review of 206 patients, 29% suffered from pleural disease (a condition affecting the lining surrounding your lungs), 43% suffered from a punctured lung, 16% developed pus in the pleural space, and 16.5% had a broncho-pleural fistula – a rare condition where there’s a passage between the bronchi and the pleural space.

This group of patients had a death rate of 24%, with 53% needing fluid to be drained from the lining of their lungs and 26% needing surgical help. Pulmonary NTM infections can cause necrotizing granulomas and chronic interstitial pneumonia, indicating ongoing damage to the lungs.

Patients with NTM and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease – a condition where blood clots block arteries in your lungs – have a higher risk of these blockages.

A list of the common side-effects caused by NTM infections:

- Pleural disease

- Punctured lung

- Puss in the pleural space

- Broncho-pleural fistula

- Necrotizing granulomas

- Chronic interstitial pneumonia

Among individuals with lung transplants, the survival rate is similar for those with and without NTM infections. Still, those with the infections often develop bronchiolitis obliterans. NTM treatment for cystic fibrosis patients can be tricky as it may change the absorption and removal rate of medication.

Complications can also occur outside of the lungs, especially in individuals with weak immune systems. This includes conditions like tenosynovitis, arthritis, and vertebral osteomyelitis that can occur after the initial lung infection. A variety of NTM species can cause these complications. In those with severe immune suppression, widespread MAC (Mycobacterium Avium Complex) infections can lead to impaired red blood cell production and increased liver enzymes. This can relate to conditions like spleen and liver enlargement and bone and joint disease, which are common complications of widespread MAC infection.

Preventing Lung Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

Preventing NTM (Nontuberculous Mycobacteria) infections can be quite difficult. This is because NTM is commonly found in our environment, which makes it tough to set up defenses against exposure. Moreover, it’s often hard to tell which people are more at risk of getting an NTM infection. For example, the bacteria has been found in hot showers, indoor swimming pools and plumbing, but not everyone exposed to these will develop an infection. It is unclear whether advising people against hot showers would help prevent infections. There isn’t much evidence to suggest strategies that limit exposure to NTM from our environment. So, it might be a good idea to discuss general safety measures with people who are at risk of getting lung infections from NTM.

When it comes to managing NTM, patients should be aware that treatment can take quite a long time. A carefully designed care plan, agreed upon by the patient and their family is vital. This includes explaining all the medication doses, scheduling follow-up appointments, and providing the contact information for healthcare professionals. The care plan should also mention the possible side effects and how long the treatment may last. Patients should be informed about any potential complications if the disease gets worse. For instance, it may take some time before the bacteria can no longer be spotted in their lung mucus (sputum culture conversion), and they might need to continue taking medicine for over a year after that to completely get rid of the disease. It’s important that healthcare providers establish trust and a healthy relationship with the patient to achieve the best results.