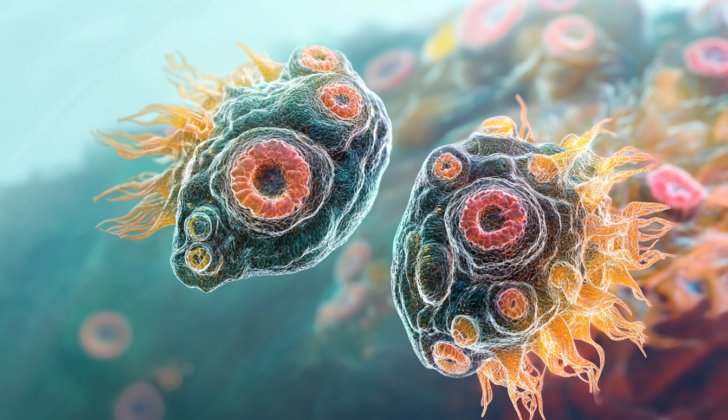

What is Naegleria (Brain-eating Amoeba)?

Naegleria fowleri, or the “brain-eating amoeba,” is a type of single-celled organism called Percolozoa. This name was given to it by Malcolm Fowler, who first discovered cases of a brain infection called primary amebic encephalitis caused by this amoeba in Australia.

Naegleria fowleri usually lives in freshwater that likely also contains soil, thriving best in high temperatures up to 45°C (113°F). It goes through three different stages in its life: cysts, trophozoites, and flagellates. The trophozoites stage involves the amoeba reproducing, and it is during this stage that it can also cause serious infections in humans. If the amoeba’s environment becomes challenging, like when food is scarce, it can convert into a temporary mobile form known as flagellates. These flagellates can then transform back into trophozoites when conditions improve again.

If the amoeba experiences harsh conditions or stress, it creates a protective shell and becomes a cyst that is about 9 micrometers wide. These cysts can survive wide temperature ranges, but cannot tolerate freezing. In warm waters, the trophozoite forms of Naegleria fowleri feed on bacteria and fungi. When the water temperature drops in the winter, they change into cysts and settle at the bottom.

What Causes Naegleria (Brain-eating Amoeba)?

N. fowleri is a type of bacteria that can cause an infection leading to a condition known as amebic meningoencephalitis, which is a serious brain infection. This infection can occur when warm freshwater goes into your nose and travels through a thin barrier in your skull called the cribriform plate, reaching your central nervous system (which includes your brain and spinal cord).

After the bacteria gets into your system, it can take anywhere from 1 to 14 days before you start experiencing symptoms of brain inflammation, known as encephalitis.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Naegleria (Brain-eating Amoeba)

Naegleria fowleri is a type of organism that can be found in various parts of the world. This organism tends to live in freshwater lakes, hot springs, pools with low chlorine levels, and warm polluted waters. However, it’s important to note that it doesn’t live in seawater. While it was first identified in Australia, cases of Naegleria fowleri infections have been reported in New Zealand, Europe, Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the United States.

- In the United States, this organism is most commonly found in the southern states.

- More recently, Naegleria fowleri has also been found in warm polluted waters in northern states, including Connecticut and Minnesota.

- Between 2008 and 2017, 34 cases were reported in the United States, and between 1962 and 2017, 143 infections linked to this organism were reported to the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

- Most commonly, infections usually occur after swimming or diving in freshwater.

- However, other cases have been reported following other types of exposure. For instance, two children in Arizona got infected at home while bathing. The water source was traced back to an untreated community well-water system.

- In Nigeria, a case was suspected to be caused by inhaling Naegleria fowleri cysts.

Signs and Symptoms of Naegleria (Brain-eating Amoeba)

The time it takes for symptoms to show, known as the incubation period, can range from 1 to 14 days. The symptoms of this disease can resemble those of bacterial meningitis. Early signs include fever, headaches, tiredness, and feelings of nausea and vomiting. If the disease progresses, it can lead to more serious symptoms like confusion, stiffness in the neck, sensitivity to light, seizures, and problems with the nerves in the brain. This condition, known as primary amebic encephalitis, advances quickly and can cause a coma and, in many cases, death.

- Incubation period of 1 to 14 days

- Early symptoms: fever, headaches, tiredness, nausea, vomiting

- Late symptoms: confusion, stiff neck, light sensitivity, seizures, brain nerve problems

- Can lead to coma and often results in death

Testing for Naegleria (Brain-eating Amoeba)

If you’ve recently been in freshwater like a lake or river and start showing signs of a severe brain and spinal cord infection like high fever, headache, stiff neck, confusion, and seizures, your doctor might suspect you have a disease called Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM). This disease is caused by a single-celled organism called Naegleria fowleri.

To help diagnose PAM, your doctor might analyze your cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is the clear fluid that surrounds your brain and spinal cord. They do this by performing a test called a lumbar puncture or a ‘spinal tap’. In this procedure, a needle is inserted into the lower part of your spine to obtain a small amount of your CSF. Once obtained, it is analyzed in the laboratory. The CSF of patients with PAM might look similar to that of patients with bacterial meningitis – the fluid might have normal to slightly lower than normal glucose (sugar) levels, high protein levels, and a higher number of white blood cells (also known as leukocytosis). The pressure of the CSF might also be elevated in patients with PAM.

Finding Naegleria fowleri in the CSF, however, can be tricky. This is because the standard laboratory techniques like Gram staining (a method used to identify bacteria) and cell culture (a method used to grow cells in a lab) may destroy the organism. Instead, doctors use special techniques, including wet mounts, hematoxylin and eosin staining, periodic acid-Schiff staining, Giemsa-Wright staining, or modified trichrome stains. These methods can help visualize the organism in the CSF.

Unfortunately, very few labs in the United States can test for Naegleria fowleri. The organism’s presence can also be confirmed by running a specialized lab test called immunohistochemical staining on your CSF or tissue sample. This test uses antibodies to identify Naegleria fowleri. Another method called Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) can also be used; this test amplifies and measures the DNA of the organism. However, testing your blood for antibodies to Naegleria fowleri (also called serological testing) might not be useful because the disease progresses so quickly that your body might not have time to produce enough antibodies before it becomes severe.

Finally, your doctor might take pictures of your brain using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). These images can help your doctor see what’s happening in your brain and might show signs of bleeding or stroke, depending on how far the disease has progressed.

Treatment Options for Naegleria (Brain-eating Amoeba)

The medical options for treating your condition are limited since we lack information from controlled trials or detailed clinical studies. However, a few medicines have been increasingly used based on lab studies or individual patient reports.

Amphotericin B (AMB) is one such medication used for Naegleria fowleri, the organism that causes your illness. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends AMB because lab studies have suggested it can effectively fight against this organism.

There’s also a drug called Miltefosine, which is traditionally used to treat breast cancer. It’s now being seen as a promising treatment for Naegleria fowleri. This medicine was initially available only through the CDC, but now you can buy it commercially.

In addition, a group of medicines called Azoles, which include fluconazole and voriconazole, are often used alongside AMB because they can reach the central nervous system and fight off the infection there. Azithromycin, another medication, has been shown in lab and animal studies to work against Naegleria fowleri, especially when used in combination with AMB. Rifampin is another drug we can use to treat your disease, but it’s necessary to be careful, since it may interact with other drugs and can affect their performance, including AMB and fluconazole.

Lastly, it is worth noting that controlled hypothermia, the medical cooling of the body, has been used successfully in a few patients– they were able to fully recover and return to their regular lives, including going back to school. This method might present a promising way to improve the recovery of patients affected by this condition.

What else can Naegleria (Brain-eating Amoeba) be?

PAM, or Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis, can mimic any brain infection. What makes diagnosis tricky is that there are no unique signs on scans or physical exams, and it can look like bacterial brain infection on fluid tests from the spine. However, a thorough look at the patient’s history, especially any possible exposure to freshwater, can hint towards PAM and increase the doctor’s suspicion about the disease.

What to expect with Naegleria (Brain-eating Amoeba)

PAM, a particular disease, often presents severe complications and a high mortality rate. In the United States, only three individuals have survived–all of whom were young and in good health to begin with. Despite the high risk associated with PAM, it’s important to note that the rate at which it occurs is quite low.

Prevention:

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CD) has shared some recommendations to prevent PAM. These include avoiding getting water up your nose. You can do this by keeping your head above water or using nose clips when swimming. It’s also suggested that you stay away from freshwater activities when water temperatures are high. If you need to rinse your nose with water – like in a neti pot or for religious rites (ablution) – make sure you’re using sterile, distilled, filtered, or boiled water. Properly disinfecting areas with water, such as swimming pools or public water systems, with chlorine can also help prevent PAM.