What is Plague?

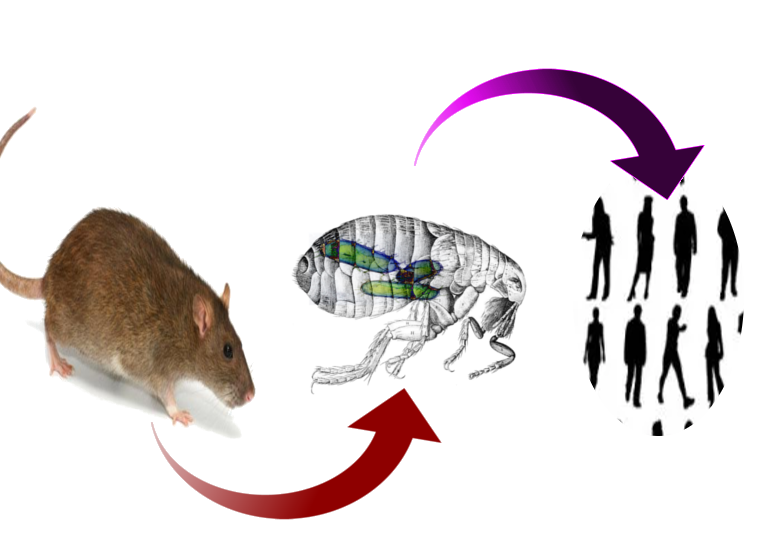

Plague is a disease that’s passed on to humans by animals and has been around for thousands of years. There are three main types of plague in humans: bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic. These are all caused by a bacteria known as Yersinia pestis. This bacteria regularly lives in insects and is then passed on to mammals like rodents or wild animals. Humans aren’t the main target of this bacteria – we just happen to get it from these animals.

Interestingly, even though we’re not its main target, Yersinia pestis has played a major role in human history. It caused three known pandemics, or global outbreaks. One of these, the Black Death in 14th century Europe, killed nearly a third of the population. The most recent plague outbreak started in the late 19th century in Asia and India, and there are still cases today in Africa. The bacteria also exists in America and Asia and can also potentially be used as a biological weapon, so there are ongoing efforts to develop a vaccine to protect against it.

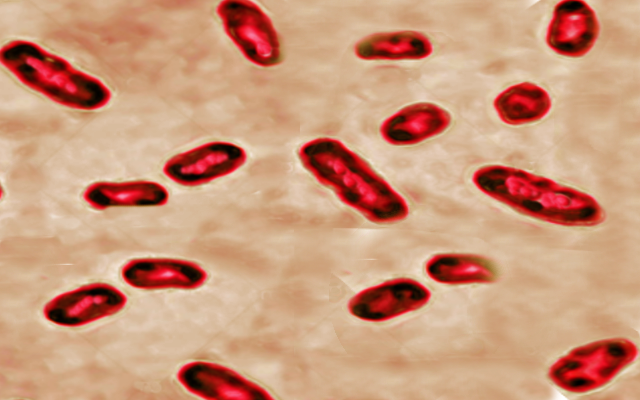

What Causes Plague?

The various symptoms of the plague come from one type of bacteria, called Yersinia pestis, which comes from the same family as harmless bacteria that live in our intestines. Many thousands of years ago, Yersinia pestis developed from a bacterium called Yersinia tuberculosis after it acquired harmful properties.

This particular bacterium normally lives in rodents, but bugs can carry it too. The most common hosts are black rats and brown sewer rats, while the most common bug to carry it is the oriental rat flea.

Usually, people catch the plague through the bite of an infected flea. However, there are other ways to get infected too. People have contracted the plague through handling infected animal tissue, breathing in the bacteria from the air, eating infected animals, and even from other humans. All these instances have been noted by doctors in the past.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Plague

The plague is a dangerous disease that has caused significant harm in three main historical episodes. The first was the Justinian Plague in the 6th Century, which affected people in the Mediterranean during the Roman emperor Justinian’s reign. The second incident, called the Black Death, transpired in 14th century Europe. Lastly, in the late 19th century, the disease initiated in China and resulted in the death of millions in China and India. Notably, in the first decade of this century, more than 21,000 cases were reported, resulting in over 1600 deaths, primarily in East and Central Africa. Currently, the plague is most active in Madagascar, where over 13,000 cases were recorded between 1998 and 2016.

On the contrary, the plague is reasonably rare in the US, where the majority of reported cases occur in comparatively uninhabited areas such as New Mexico, Colorado, California, and Texas. The plague affects both sexes and all ages, although there seems to be a slight inclination towards males and children in recent years.

- The plague can occur in any season, but it typically depends on the local rodent and vector ecology. For instance, in Madagascar, the plague season is from September to March, while in the US, it’s between February and August.

- Anyone can get the plague, but it may affect males and children slightly more.

- The biggest risk for the plague is being exposed to the insect that carries it and the rodents that host it. This is especially common in places where the disease is active.

- People can also get the plague from an infected cat’s bite or scratch.

- The plague is more common in warmer climates, especially among those living in poverty and in areas with unsecured shelter.

- In the United States, the risk of plague is highest in the southwestern states, with half of the cases occurring in young people aged 12 to 45 years. It’s common amongst those who do a lot of outdoor activities.

It’s extremely important to report any suspect plague instances to your local health department. In the United States, information about these cases is usually collected by the Centers for Disease Control via local and state agencies.

Signs and Symptoms of Plague

Y. pestis infection, or bubonic plague, starts with a flea bite followed by a 2-to-8-day incubation period. In around a quarter of cases, a skin lesion can form at the site of the bite. These lesions can take various forms, including pustules, blisters, bumps, or scabs, and are often overlooked. After this, people typically suddenly experience fever, chills, headache, and general weakness.

Within a day, a painful swelling known as a ‘bubo’ develops in the area of regional lymph nodes, most commonly the groin, but sometimes the armpits or neck. At first, the bubo is just painful, but soon swelling occurs, causing so much pain that individuals may avoid moving. A bubo can be a single lump or a cluster of nodes, and the skin above it is typically warm. Alongside fever, other signs include a rapid heart rate and low blood pressure that can lead to shock. Hepatosplenomegaly, or enlargement of the liver and spleen, might also be found during a physical examination.

Septicemic plague shows similar signs to bubonic plague but without the bubo. Pneumonic plague, which can either be a primary condition or a secondary location of the infection, generally follows the spread from the bubo and leads to cough, chest pain, and coughing up blood, on top of the typical high fever tied to the plague. This can happen with or without buboes.

Inhalational pneumonic plague happens when exposed to a pneumonic plague patient with a cough. Rarer presentations include meningitis, usually following untreated bubonic plague, and pharyngitis, which appears similar to other forms of pharyngitis with significant swelling of the frontside neck lymph nodes. The plague may also occasionally present with strong feelings of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain before the appearance of buboes or sepsis, making an initial diagnosis difficult.

Testing for Plague

If your doctor suspects that you might have the plague, you’ll have to get a series of tests to confirm this. For a type of plague called pneumonic plague, the Centers for Disease Control recommends following certain precautions for 48 hours after starting your antibiotics. This is to make sure the disease doesn’t spread to others. It’s super important that the lab staff knows about the suspicion, because pneumonic plague can be passed on through regular handling of samples and cultures.

To determine if you have Y. pestis, the bacteria that causes plague, several conditions need to be considered by your doctor. They might suspect you have plague if you have a fever after being in contact with rodents in certain areas, if you have swollen glands coupled with fever and low blood pressure, or if certain bacteria (gram-negative bacilli) are found in your system, especially if you have pneumonia with bloody cough. Any gram-negative bacilli found in a sample taken from your lymph nodes could also be a strong indication of plague, because few similar bacteria cause gland swelling.

Your doctor might get an aspirate from any conspicuous glands, which is then stained and cultured to identify the bacteria. Also, full blood counts could reveal abnormally high white blood cell counts along with low platelet counts, a condition known as thrombocytopenia. White blood cells in affected patients might show certain changes, although it’s not entirely clear how common or specific these changes are for this condition.

In places where the disease is prevalent, like Madagascar, rapid testing using a specific component called the F1 antigen is common. There are various tests available with different accuracies including immunofluorescence, PCR, and ELISA. The choice of test would depend on what resources are available and how common the disease is in your locality. In the United States, cultures can be sent to the CDC for confirmation.

Treatment Options for Plague

Antibiotics are crucial in treating the plague, and they need to be administered as soon as possible because the disease progresses rapidly and can lead to severe outcomes. Doctors typically begin treatment as soon as they suspect a plague infection, without waiting for test results. Medications called “aminoglycosides” are usually the first choice for treatment; gentamicin, a type of aminoglycoside, is gradually becoming the preferred choice over streptomycin, which was traditionally used.

If aminoglycosides are not suitable, alternatives such as doxycycline and tetracycline could be used. However, these antibiotics need to be taken for a longer period (14 days instead of the usual 7 to 10 days) because they work by inhibiting the growth of bacteria, not killing them directly. Some doctors may also recommend Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, but this drug is usually less effective compared to the first-line treatments. If the plague infection has spread to the meningitis, a condition when the protective membranes of the brain and spinal cord are inflamed, Chloramphenicol is typically used.

Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of levofloxacin for treating plague, based on studies performed on animals and in the lab. Despite the risk of plague spreading widely through bio – terror, vaccines to prevent the infection are not widely used because there are doubts about how effective they are. However, there are as many as 17 vaccines currently being developed.

What else can Plague be?

The diagnosis of plague can be challenging due to its broad range of symptoms which overlap with many other conditions. This is why doctors need to have a high level of suspicion for the disease, especially in patients who are seriously ill.

When it comes to bubonic plague, they need to consider other conditions that also cause swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy). These include various bacterial, viral, and fungal infections, cancer, side effects from certain medications, autoimmune diseases, and other conditions causing inflammation.

Yet, bubonic plague stands out because of how suddenly the person’s temperature spikes and the rapid development of painful, swollen lymph nodes (buboes). This condition progresses quickly, leading to severe inflammation of the lymph nodes and rapid deterioration of the patient’s condition.

Similarly, when people have symptoms like coughing up blood (hemoptysis) and fever, the diseases that need to be ruled out can range from viral bronchitis and different types of pneumonia (particularly tuberculosis), to pulmonary embolism, inflammation, and cancer. However, the sudden and severe onset of symptoms along with the presence of buboes tends to suggest plague over other conditions.

In cases of septicemic plague, the symptoms like fever and lower blood pressure are pretty common, seen in a variety of infectious conditions, inflammation, and any condition leading to shock. Therefore, the best way to reach a definitive diagnosis is through initial clinical suspicion followed by laboratory testing.

It’s worth noting that plague cases related to travel have been reported in the United States. So, high suspicion for plague should be held especially when the patient lives in or recently visited plague-endemic areas.

What to expect with Plague

The outlook for all forms of plague is generally not good. The bubonic plague has an estimated death rate of 50 to 90% if not treated. The septicemic plague, another form of plague, has a slightly lower death rate, around 22%. However, if these conditions are properly diagnosed and treated early, the death rate can be decreased to between 5 and 15%.

Presently, for all known cases, the death rate is about 7%. The pneumonic plague, another variant of the plague, is often deadly unless treated right after exposure or within the first day of getting sick. Even with the right treatment, the death rate stays over 50%.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Plague

There are many possible complications that can arise from the plague, which can range from death to other variations of the typically known bubonic plague. Some of the major complications include a sore throat (pharyngitis), a serious lung infection (secondary pneumonic plague), bacteria in the blood (bacteremia) and septic shock, which is a severe infection that can cause your organs to fail. Another complication is meningitis, or inflammation of the brain and spinal cord’s protective membranes, which usually occurs a week after untreated bubonic plague and makes the situation worse.

Key Possible Complications:

- Death

- Variations of bubonic plague

- Sore throat (Pharyngitis)

- Serious lung infection (Secondary pneumonic plague)

- Bacteria in the blood (Bacteremia)

- Septic shock (a severe and often deadly infection)

- Meningitis (brain and spinal cord inflammation)

Preventing Plague

In areas of Uganda where plague is common, the unpredictable nature of the disease and its outbreaks make it difficult for both public health officials and patients to recognize the condition. Plague is even less common in the US, and not many people are familiar with the risk factors for catching the disease or the symptoms to watch out for. The most important measure to prevent infection is to steer clear of any dead rodents.

If you live in an area where plague is common, you can protect yourself by avoiding fleas and rodents. This can be done by living in houses where rodents cannot enter, wearing shoes and clothes that cover the legs, and using bug spray in the home when needed. It’s also advisable to keep away from sick cats and not to handle dead animals without wearing gloves.

If you worry that you may have been exposed to plague, it’s important to seek medical care if you develop a fever, swollen glands, a cough that may or may not bring up blood, a stiff neck and headache, or a sore throat. Getting treatment early is crucial as it can lower the risk of death and complications from the disease.