What is Vertical Transplacental Infections?

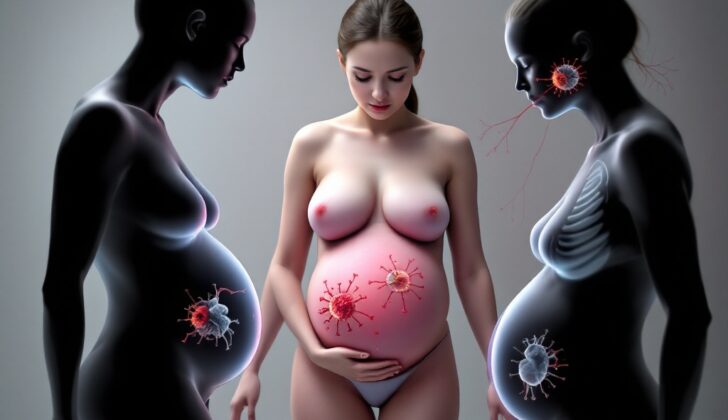

While many people are familiar with catching an infection from someone else in the community, there’s another form of infection transmission that happens from a pregnant individual to their unborn child. This is known as vertical transmission, as opposed to horizontal transmission which occurs between individuals.

The study of infections passed on during pregnancy is often categorised by when the infection happens: before birth (antenatal), during birth (perinatal), or after birth (postnatal). One special category we focus on is infections that cross the protective barrier of the placenta and potentially harm the developing baby, leading to conditions that can range from mild sickness to severe birth defects or even fetal death.

There are several infections that have historically been associated with this type of transmission, which we refer to as “ToRCHes” (toxoplasmosis, other [hepatitis B virus and syphilis], rubella, cytomegalovirus [CMV], and herpes simplex virus). In addition to these, infections like Listeria, HIV, parvovirus B19, varicella-zoster virus, hepatitis C virus, and Zika virus can also cross the placenta. The impact each infection can have on fetal development varies greatly – much depends on when during pregnancy the infection is acquired and what specific virus or bacteria is involved.

Our additional guides titled “Antepartum infections,” “HIV in Pregnancy,” and “Pregnancy and Viral Hepatitis,” provide more detailed information on these infections that are transmitted from mother to child and the complications they could cause during childbirth.

What Causes Vertical Transplacental Infections?

When a mother has an infection, there’s a chance that it could pass to the baby while they’re in the womb. There are many ways a mother can get an infection – through sexual contact, eating contaminated food, or being bitten by bugs like ticks and mosquitoes. But how these infections can then cross the barrier of the placenta to the developing baby is still not entirely understood, and can vary with different diseases. Certain cells in the placenta play a key role in stopping infections from crossing over to the baby.

Sometimes, if a pregnant person gets a primary infection, which means it’s the first time they’ve caught a particular disease, the disease can infiltrate the bloodstream and find a way through the placenta and infect the baby. This is also more likely to happen if there are a lot of disease-causing agents present or if there’s been some damage to the placenta.

Certain sexually transmitted infections can pass from the mother to the baby. Syphilis is one such disease and can pass onto the baby at any stage of pregnancy if the mother is infected. The disease can then cause more severe complications if the baby gets it later in the pregnancy.

The herpes viruses can also pass from mother to baby during pregnancy but this happens very rarely. More commonly, the baby catches the virus during birth. If the baby gets the disease during pregnancy, the illness is usually more severe.

Infections like HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C can also be passed through sexual contact, drug use, or contact with infected blood or body fluids. The baby usually catches these diseases during birth, but sometimes the diseases can pass through the placenta to the baby while they’re in the womb. This is especially true if the mother has a lot of the disease in her blood stream.

Contaminated food can also lead to diseases that can pass from mother to baby during pregnancy. Toxoplasmosis and listeriosis are such diseases that pregnant people can get from eating contaminated food, which can then potentially infect the baby.

Diseases can also be passed through respiratory droplets. Diseases like human parvovirus B19, rubella virus and varicella-zoster virus (which causes chickenpox and shingles) can infect the pregnant person and then pass over to the baby through the placenta.

Lastly, Zika virus which is mostly transmitted through bites from infected mosquitoes and sometimes through sexual contact, can cross the placental barrier and infect the baby in the womb. It can also influence the brain of the baby, causing malformations.

Each one of these diseases has its own unique way to pass from mother to baby and can present varying risks to the baby’s health based on when during the pregnancy they catch the disease. However, in some cases, early detection and treatment can reduce these risks.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Vertical Transplacental Infections

Different research doesn’t always separate infections that babies can get while still in the womb from the ones they can get during birth. The following information focuses on diseases that can pass from mother to baby mostly through the placenta before birth.

Here are some diseases and relevant data:

- Syphilis: Congenital Syphilis is most common in low- and middle-income countries, although there’s been a rise in cases in high-income countries over the last decade. In 2016, average global cases were approximately 425 per 100,000 live births, a figure that stayed largely the same in 2020. The United States saw an increase from 941 cases in 2017 to 2677 in 2021. However, these data likely underestimate the true burden of syphilis due to undiagnosed or symptomless infections. Decreased testing during the COVID-19 pandemic has played a role in increasing the case numbers.

- Hepatitis C Virus (HCV): The geographic spread of HCV is similar to syphilis, with prevalence among pregnant women being higher in lower-income countries. However, it’s decreasing over time. Of children born to HCV antibody-positive and RNA-positive women, about 5.8% develop HCV infection, while this is about 10.8% for those born to HCV- and HIV-positive mothers.

- Toxoplasmosis: The most solid data for congenital toxoplasmosis come from France and Brazil. However, it’s not all bad news: the prevalence of the infection agent T. gondii in childbearing-age women in the U.S. dropped from 15% (1988-1994) to 9% (2009-2010). Still, 91% of the women in the U.S. are at risk of primary infection.

- Listeriosis: It’s difficult to know the full extent of listeriosis infections because mild cases may go unnoticed or untested. In the U.S., the average infection rate was 4.5 per 100,000 pregnancies between 2004 and 2009. Consumption of Mexican-style soft cheeses was identified as a major risk factor, especially for the Hispanic population.

- Cytomegalovirus: This is common in respiratory illnesses. A 2007 study estimated that 0.64% of all live-born infants were affected.

- Parvovirus B19: Pregnant women who are initially exposed to this virus are estimated to pass the infection to the fetus in about 17%-35% of cases.

- Rubella and Varicella: Widespread vaccine availability has significantly decreased the rates of these diseases. For example, Rubella rates have fallen from between 0.1-0.2 cases per 1,000 live births to fewer than 1 case per 100,000 live births since the vaccine’s introduction. However, vaccination coverage only reaches 70% of the global population.

- Zika Virus (ZIKV): Before 2007, ZIKV cases were only reported in Africa and Southeast Asia. Since then, it has spread to other regions, with different incidence rates. Vertical transmission (from mother to baby) was suspected to occur in about 20%-30% of cases.

Signs and Symptoms of Vertical Transplacental Infections

Vertical transplacental infections can cause symptoms in pregnant individuals, as well as their fetus or newborn child. Usually, symptoms in a fetus are detected through antenatal ultrasonography during pregnancy. As part of the medical evaluation, a detailed interview with the patient about several factors including sexual history, occupational exposure, diet, travel, and substance use, is necessary.

If the pregnant individual shows symptoms, then a thorough physical examination and fetal ultrasonography are performed. Ultrasonography may show various changes including brain, abdominal, and liver calcifications, reduced head size, heart deformities, abnormal limb formation, enlargement of the liver and spleen, changes in bowel or kidney appearance, fluid accumulation in the abdomen, increase in brain ventricle size, severe anemia causing fluid overload, and growth restriction. In a newborn, signs to look for are fever, signs of infection, low birth weight, small head size, clouding of the eye lenses, skin rashes, purpuric skin spots resembling a blueberry muffin, petechiae (small spots due to bleeding under the skin), jaundice, enlargement of the liver and spleen, and swelling of the lymph nodes.

Some signs in fetuses and neonates are linked to specific infections. For instance, early onset of sepsis is commonly seen in listeriosis. Small head size can be an indicator of rubella syndrome or infections caused by CMV, Human herpesvirus 1 or 2, Toxoplasma gondii, and Zika virus. Eye abnormalities such as cataracts can indicate rubella, varicella syndromes, CMV, or Toxoplasma gondii infection. Underdeveloped lower extremities and small eyes are often observed in varicella syndrome. Conditions like low birth weight, being small for gestational age, and enlargement of the liver and spleen are generally associated with transplacental infections.

Newborns with CMV are likely to have several abnormal findings (in about 91% of cases). Only in about 8% of cases, an isolated symptom is observed. In one study, the most common symptom for infants with CMV was petechiae (small spots due to bleeding under the skin), seen in 74% of cases. However, hydrocephalus (water on the brain) and intracranial calcifications are classically reported. The presence of a blueberry muffin-like rash is typically associated with many TORCH infections; but it’s thought to be induced due to an increase in red blood cell production within the skin, and only rubella and CMV have been confirmed to cause this through a skin biopsy.

Testing for Vertical Transplacental Infections

If a pregnant individual or their newborn is suspected of having a vertical transplacental infection, they would need to be evaluated. In the United States, the standard prenatal screening process typically includes routine testing for infections like HIV, Hepatitis B and C, Syphilis, Rubella, and Varicella, and in high-risk areas, toxoplasmosis as well. These tests help to detect infections that can be passed from mother to baby during pregnancy. These tests should be repeated if new risk factors develop during the pregnancy. Risk factors largely inform the need for further neonatal and maternal evaluation.

For Syphilis, newborns whose mothers tested positive at any stage during pregnancy should also have tests at birth. Further tests, which could include a complete blood count, a lumbar puncture, or bone scans for bone damage, might be required depending on the baby’s physical examination results, the newborn and maternal Syphilis stages, and the mother’s treatment history.

For Hepatitis C Virus, it is suitable to test babies at around 18 months old or when they are between 1 to 2 months old. If the infection is detected, it’s important to monitor liver function regularly.

If a pregnant individual is suspected of having a Toxoplasmosis infection, further tests should first include a search for immune response markers (IgG and IgM), followed by an examination of other factors if needed. If the fetus is suspected to be infected after 18 weeks of pregnancy, a polymerase chain reaction test (which detects the presence of the infection’s genetic material) can be performed on amniotic fluid. The fetus should then be monitored at least monthly via ultrasound.

Concerning Listeriosis, fever in a pregnant person or signs of early-onset sepsis in an infant may necessitate further tests. These could include a blood culture, a placental culture, or a cerebrospinal fluid evaluation.

Cytomegalovirus evaluation can be prompted by abnormal findings on a fetus’s ultrasound. Tests can include searching for immune response markers (IgG and IgM), or repeatedly testing for immune response. Additional tests for newborns can involve blood counts, testing liver, kidney, and coagulation, as well as ultrasound, eye examination, and hearing evaluation.

For Parvovirus B19, pregnant individuals exposed to the virus should be tested for immune response as soon as the exposure occurs. Depending on the test results, further monitoring might be needed for potential fetal infection and anemia.

All pregnant people should be tested for the Rubella Virus as soon as possible. The child might need to undergo a range of tests after birth if the mother does not have immunity and signs are present. These can include tests on bodily fluids for viral culture or detection.

Acute varicella viral skin infection, or chickenpox, can usually be diagnosed based on the finding of a classic itchy, blister-like rash. If further tests on the unborn child are needed, ultrasound may be employed.

For the Zika Virus, appropriate testing is recommended as soon as possible if there’s a suspicion of infection during the pregnancy. Additional tests could be carried out in some situations. If the infection is confirmed, regular fetal ultrasound evaluations should be done to monitor the effects on the fetus.

Treatment Options for Vertical Transplacental Infections

Managing infections that pass from a mother to her child during pregnancy, also known as transplacental infections, depends on when the infection is diagnosed. Let’s look at the treatments for a few different types of these infections.

Syphilis: Penicillin G is the primary treatment for syphilis. It is given to everyone, including pregnant people, newborn babies, and infants. The method of giving the penicillin (by a muscle injection or an IV) and the number of doses depends on the stage of the disease. For newborns, the penicillin is always given through an IV for 10 days.

Hepatitis C Virus: Currently, there are no treatment options if Hepatitis C is diagnosed during pregnancy. If the baby is also diagnosed with Hepatitis C after birth, treatment is usually postponed until they are 3 years or older.

Toxoplasmosis: This is a disease that can be passed from a mother to her baby during pregnancy. If diagnosed early in pregnancy, spiramycin is given. However, if the fetus shows signs of having the disease as well, the treatment is changed to a combination of pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid. The treatment for newborn babies with toxoplasmosis varies widely and has not been clearly defined.

Listeriosis: If a pregnant person has listeriosis, a type of bacterial infection, the preferred treatment is high-dose IV ampicillin for at least 14 days, sometimes combined with gentamicin. Infants with listeriosis are treated similarly.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV): There is currently no standard treatment for CMV infection in pregnant people or their babies. An antiviral drug named valacyclovir might be effective, but it’s only used in research settings. However, valacyclovir is recommended for moderate to severe postpartum illnesses. It is typically taken for at least 6 months.

Parvovirus B19: There are no treatment options for this type of infection. If the mother or fetus has parvovirus B19, the baby is monitored for hydrops fetalis and fetal anemia, two potential complications.

Rubella Virus: There are no specific treatment options for rubella infections. The best way to manage it is to prevent it with vaccination and manage any complications that arise.

Varicella Virus: If a pregnant person or their baby has a varicella infection, oral acyclovir given early can reduce the duration of symptoms

Zika Virus: Similar to rubella, there are no specific treatment options for the Zika virus. Instead, the focus is on preventing exposure and managing complications of the infection.

Remember, each situation varies, so the best source of advice on this topic is to stay in close communication with your healthcare provider if you have any questions or concerns.

What else can Vertical Transplacental Infections be?

If a pregnant person, their fetus, or a newborn baby shows signs that suggest the presence of a disease passed from mother to child through the placenta, there are numerous possible diagnoses. Such diseases can appear in many ways and can look like several other conditions. Here are some of the diagnoses that doctors will often consider:

- Autoimmune diseases that can lead to problems with the placenta

- Chromosomal abnormalities like Trisomy 21, Trisomy 18, and Trisomy 13, which may cause slowed growth and physical irregularities

- Genetic syndromes

- Effects of harmful environmental or drug-related exposures

- Specific cell conditions or other blood-related or cancer-related diseases such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Infections that were not acquired through the placenta

What to expect with Vertical Transplacental Infections

The outcome of infections that are transferred from a pregnant individual to their baby during pregnancy can greatly depend on the timing of the diagnosis and treatment as well as the severity of the infection, which can vary greatly. Research usually focuses on the baby’s and infant’s outcomes, yet the aftereffects on the pregnant individual should not be ignored.

In the case of Syphilis, a study in the United States projected a death rate of 31% due to syphilis during pregnancy, primarily from baby deaths in the third trimester. The baby’s weight might be lower than expected. However, most infants were healthy at the last check-up.

When it comes to Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), the main concern is the infection turning into a chronic one, leading to liver inflammation and, eventually, severe liver disease. Progression to chronic infection is suspected to be significantly lower in children compared to adults, with about half of infected children developing it. In the long run, outcomes are generally positive, but they do vary a lot between different studies.

In remembering old studies on Toxoplasmosis, it’s a bit tough to predict the outcomes of congenital T gondii infection. However, numerous studies point out that an infant might show no immediate signs but untreated or poorly treated cases can cause eye damage affecting vision. Although treated cases may still develop long-term complications, their chance of developing neurological problems is quite low, at around 2%.

For pregnant individuals with Listeriosis, the prognosis is generally good. However, the outcomes for the baby and neonate (newborn) are notably worse, with a chance of miscarriage, stillbirth, and developing neonatal listeriosis. Of the surviving infants, most recovered completely, a quarter died, and 12.7% had unresolved neurological or other complications.

Neonatal Cytomegalovirus infections have diverse outcomes, depending on the symptoms. Overall, symptoms were noted in around 11% of infected babies. Follow-ups revealed varying degrees of neurological complications with some infants experiencing hearing loss, developmental delays, cerebral palsy, and learning difficulties, and severe disability or multiple problems in the worst cases. Treating with ganciclovir (an antiviral medication) seems to improve hearing results, but the best treatment duration and long-term effects are still unclear.

During the Parvovirus B19 outbreaks, the virus seems to contribute minimally to the total fetal loss. Pregnant individuals with this virus are more prone to fetal loss, abortion, and stillbirth. Abnormal neurodevelopment was present in nearly 10% of those who survived fetal hydrops (a severe condition leading to swelling in the fetus).

Long-term outcomes of the Rubella Virus can include deafness, eye issues, aortic valve sclerosis (hardening of the aortic valve in the heart), diabetes, early menopause, and osteoporosis, all likely to occur more than in the general population. About one in four studied patients were found to have higher levels of certain antigens (part of the immune response), which are associated with autoimmune conditions.

Infants affected by the Varicella Virus (causing chickenpox) can have a high mortality rate up to 30 months post-birth and a 15% risk of developing zoster (shingles) in the first couple of years. After this challenging initial period, however, the long-term outcome can turn out well.

In the case of the Zika Virus, a study from Brazil showed that the mortality rate ranged from 4% to 6% among infants with confirmed or potential infection. The study also found that 31.5% of infants between 7 and 32 months had below-average developmental scores. Female sex, term delivery, normal eye examinations, and maternal infection in later stages of pregnancy were factors associated with improved developmental outcomes.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Vertical Transplacental Infections

Infections that pass from a mother to her unborn child can lead to a variety of serious health problems for both the mother and the newborn or fetus. The type of health problems that occur depends on when the infection occurs and how severe it is. This is why it’s crucial to identify and manage these infections early. For more information about specific health problems related to these infections, check out the sections on Evaluation and Prognosis.

Common Complications:

- Varying health problems in pregnant or postpartum individuals

- Health risks for the fetus or infant

- Health issues depending on the timing and severity of the infection

- Importance of early detection and management

Preventing Vertical Transplacental Infections

To prevent infections that can pass from a mother to her baby during pregnancy (known as transplacental infections), it’s crucial to educate the patient on how to avoid situations that could cause these infections. More tips on preventing infections can be found in the section discussing the causes of the infections.

Doctors should underline the importance of regular check-ups during pregnancy and subsequent follow-ups. This practice allows for the early spotting and treatment possible infections. If there are vaccines available to prevent certain diseases, such as rubella and chickenpox (varicella), doctors will advise the patient to have these vaccinations as part of pre-pregnancy planning and care.

Through proactive education about prevention and taking preventive steps, doctors can significantly lower the chances of mother-to-baby infections during pregnancy, helping to protect both the health of the mother and the baby.