What is Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)?

Temporal bone fractures, which are fractures in the skull, are relatively rare, happening in about half of serious head injuries. When they do happen, they can affect many important areas, possibly leading to immediate and long-term disabilities. These fractures require a great force and are often accompanied by other injuries such as internal head bleeding, neck fractures, and other bone and muscle injuries.

Different from other fractures in the head and neck, the treatment of temporal bone fractures concentrates more on addressing the challenges brought about by the damage, rather than trying to fix the fracture itself. This is because the temporal bone is not weight-bearing, and it rarely affects the physical appearance due to the fracture. However, the damage to the facial nerve and damage resulting in hearing and balance issues can significantly affect patients, potentially causing a significant reduction in their quality of life.

What Causes Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)?

In adults, fractures of the temporal bone, found in the skull, are most commonly caused by car accidents (55%). Falls account for the second most common cause (25%), followed by work-related accidents (16%), and physical assaults (4%). For children, while car accidents can cause these fractures (30%), falls are in fact the cause of 60% of the cases.

Most of these fractures happen when a force hits the skull from the side. However, blows to the front or back of the skull can also cause these fractures. These can lead to more complex injuries that cut across the petrous pyramid – a section of the skull near the ear that encloses parts of the inner ear such as the cochlea, vestibule, and semicircular canals.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)

Temporal bone fractures, or breaks in the bone surrounding the ear, can happen at any age. They are most common, however, in people in their 20s to 40s and are three times more likely to occur in men than women. These fractures can lead to complications such as facial paralysis, which is seen in 7 to 12% of fractures. Facial paralysis usually happens because of a fracture on one side (83%) but can occur with fractures on both sides (5%) or even when a fracture isn’t apparent on an x-ray (12%).

Both sides getting fractured happens in about 17% of patients. When only one side gets fractured, it is equally likely to be the left or the right side. Temporal bone fractures can also lead to other problems, including:

- Conductive hearing loss (66% of patients)

- Bloody discharge from the ear (61%)

- Blood behind the eardrum (56%)

- Tear in the eardrum (26%)

- Leak of brain fluid (9%)

- Sensorineural hearing loss – damage to the nerves of the ear (5%).

Overall, between 30 and 70% of people with a blunt head injury will also have a temporal bone fracture.

Signs and Symptoms of Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)

It can sometimes be challenging to examine a patient comprehensively, especially when the patient is unconscious after a traumatic incident and may be in intensive care. Even though wounds, bruises, bleeding from the ear and changes to the shape of bones can be seen without the patient’s cooperation, assessing their facial nerves and hearing can prove difficult. Ideally, we should check facial function before sedating the patient, but this can be hard in emergencies.

While it’s not likely, about 1 out of 10 patients with a fracture in the temporal bone (the bone near the ear) may face facial paralysis. Understanding if their facial functions were normal immediately after the injury or not is important. Complete paralysis could indicate that the facial nerve was severed. However, if the paralysis developed slowly over hours or days, it’s usually caused by swelling of the facial nerve and can be treated medically. If the exact time at which paralysis occurred is unclear, it should be treated as if it happened immediately. There’s a classification system used to describe the severity of facial paralysis:

- Grade I: normal function

- Grade II: minor issues with movement, can close eyes with slight effort

- Grade III: moderate issues, can close eyes with full effort

- Grade IV: moderate issues, can’t completely close eyes even with full effort

- Grade V: severe issues, significant asymmetry and can’t close eye fully

- Grade VI: extreme issues, completely asymmetrical and no movement

If a patient experiences paralysis after an injury to the temporal bone, the medical team must understand if the paralysis was immediate or occurred over a period of time and how severe it is (using the grading system). When immediate and complete paralysis takes place, the nerve may be severed. Mostly, these cases are rare. However, delayed/incomplete paralysis doesn’t generally lead to the nerve being severed, and the patient can be treated conservatively. Complete and immediate paralysis cases require additional evaluation. It’s also essential to assess the cornea frequently until the eye-closing ability returns, as the lack of this ability could lead to corneal injuries.

Examinating the ear should focus on identifying any cuts or disfigurements indicating a fracture, and whether any fluid is leaking from the ear. Indeed,

fluid indicates a perforated eardrum. If significant bleeding occurs, it may require addressing in an operating room. The eardrum should also be examined to see if it’s intact. Hearing can be initially assessed via a bedside test with a tuning fork. Testing the neurological and vestibular (balance) systems is also crucial. Lastly, feeling the head to assess any changes in the shape of the skull is important.

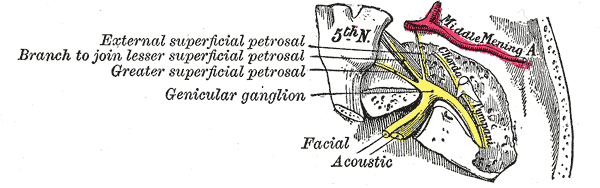

indicates the approximate location of the facial nerve within the internal

auditory canal.

Testing for Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)

High-resolution CT scans are the top method for diagnosing and categorizing temporal bone fractures. In severe injuries, a CT scan forms part of the initial trauma assessment. If not, a CT scan of the temporal bone should be ordered in instances that include facial paralysis, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, suspected vessel injury, or when surgical intervention is anticipated. Hearing loss on its own doesn’t generally require a CT scan. CT angiography is superior if a blood vessel injury is suspected. The CT scan will inform whether the fracture is sparing or disrupting the otic capsule and whether the Fallopian canal of the facial nerve is involved.

Patients with complete paralysis (House-Brackmann VI) on the same side as the temporal bone fracture can benefit from testing the facial nerve to determine prognosis and candidacy for facial nerve decompression. ENoG is the most used test method. However, it should only be done three days after the fracture to allow for Wallerian degeneration, the process in which injured nerve fibers degenerate to allow for regrowth. If ENoG is performed too soon, the severity of the injury may be underestimated.

For Bell’s palsy patients, facial nerve decompression isn’t beneficial if it’s performed after 14 days, but that isn’t the case for temporal bone fractures. Patients with facial paralysis due to a temporal bone trauma may still benefit from facial nerve decompression up to two months after the injury. If there’s no improvement or indication of candidacy for decompression after two months, it may not improve outcomes.

Hearing tests, particularly acoustic reflex tests, can be helpful in identifying any hearing loss, its type, and whether there’s a facial nerve injury in the case of temporal bone fractures. If clear fluid drains from the ear canal or nose, the fluid should be tested for β-2 transferrin or β-trace protein to determine if it’s CSF. If those tests aren’t available, the glucose content can be measured. If there’s a risk of the eye on the injured side not closing properly, fluorescein testing will reveal the presence of corneal abrasions or exposure keratopathy.

scan shows a right temporal bone fracture with ossicular disruption.

Treatment Options for Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)

There’s a debate among doctors about the right way to help if an accident, or fracture, breaks the bone near your ear and affects your facial nerves. Some believe immediate surgery is necessary, while others prefer to wait three days before conducting a test called ENoG. When this test shows more than 90% drop in the nerve’s ability to conduct signals, then doctors suggest surgery called facial nerve decompression.

There are two types of procedures that can be used:

1. Middle Fossa Craniotomy: This surgical procedure allows doctors to reach the nerve bundle near the ear.

2. Transmastoid Approach: This surgery exposes the nerve from two points near the ear, called the geniculate ganglion and stylomastoid foramen.

If the injury is severe, doctors will suggest the transmastoid approach. If you’re unable to hear because of the fracture, they might use a method called a translabyrinthine approach, which exposes the entire sensitive nerve.

Sometimes, if the nerve is seriously damaged and cannot be fixed through regular means, a cable graft may be necessary. This involves taking nerves from the leg (sural nerve) or the ear (greater auricular nerve) to replace the damaged ones. If even half of the nerve is damaged, a cable graft is recommended.

Whether or not you undergo decompression, doctors recommend a two-week course of high-dose oral steroids to help with recovery.

The recovery time and extent of recovery greatly depend on the injury’s severity and your overall health. In some cases, an eyelid weight may be needed to protect your eye from drying out or getting ulcers. Most patients will eventually recover enough to have the weight removed.

Other reasons for surgery include: persistent leakage of our body’s fluid, uncontrolled bleeding despite bandaging, damage to the chain of small bones in the ear, persistent holes in the eardrum, blockage of the ear canal, and tissue trapped in a way that risks the development of a growth called cholesteatoma.

What else can Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull) be?

If someone suddenly has facial paralysis after experiencing a head injury, the most common cause is a fracture in their temporal bone, which is part of the skull. But, other issues related to a head injury can also cause facial paralysis, like injuries to the brainstem and the cortex (the outer layer of the brain). Usually, these injuries also cause paralysis in different parts of the face.

However, a stroke typically doesn’t cause facial paralysis alone. It usually also comes with symptoms such as headache, nausea, vomiting, unstable vital signs, and potentially weak limbs.

Other reasons for sudden facial paralysis can include viral syndromes like Ramsay Hunt Syndrome and Bell’s Palsy, as well as infections like Lyme disease, HIV, and polio. Some people might also get facial paralysis due to autoimmune conditions like Guillain-Barré syndrome and multiple sclerosis, or due to tumours or injuries caused by medical procedures.

Similarly, there are a lot of potential reasons for sudden hearing loss or dizziness. These can include anything from damage caused by changes in pressure (barotrauma) or loud noises, to ear conditions like cholesteatoma or autoimmune inner ear disease. People could also experience these symptoms due to infections, Ménière’s disease, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), tumours, and many other causes.

Even with all these potential causes, if someone has recently experienced head trauma, doctors will focus on checking whether they have a fracture in their temporal bone. And, if someone has clear fluid draining from their ear (otorrhea) or nose (rhinorrhea) after a head injury, doctors will prioritize checking for a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. This is an essential step when treating patients who’ve had a head injury.

What to expect with Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)

Most people who have facial paralysis due to a fracture in the temporal bone (a part of the skull near the ear) are likely to make a recovery, though they may experience involuntary movement. Only those with the most severe form of paralysis, as rated by the House-Brackmann scale, are at risk of remaining at this level. Even so, most of these patients will improve to a less severe rating on the scale.

Patients with immediate severe paralysis are at the biggest risk of remaining paralyzed because if the facial nerve is even partly intact after the fracture, it can regenerate and restore some movement.

On the other hand, if the paralysis develops slowly, regardless of how serious it is, the patient would not worsen beyond a particular level of impairment as graded on the House-Brackmann scale. Patients who meet specific severity criteria for a type of surgery called decompression tend to fare worse than those who do not.

In a study published in 2001, patients who underwent surgery had a high chance of returning to a less severe rating on the House-Brackmann scale within one to two years. This finding significantly differs from patients who were treated with steroids and did not qualify for surgery, where they had a near-certain chance of returning to a less severe rating within a month, and a complete chance within a year.

A review conducted in 2010 sought to look more specifically at recovery rates: patients who had surgery had a 23% chance of returning to full normal function; patients who received only steroids had a 67% chance, and those who were just observed had a 66% chance.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)

Facial nerve injury from a fracture in the temporal bone, a part of the skull, can cause a long-term condition known as facial synkinesis. This condition involves involuntary spasms and movements of the face, including tension and soreness, triggered by intended facial movements. This is caused by the incorrect regrowth of facial nerves following the injury. These misconnections can lead to higher resting muscle tone causing tension and soreness, or they can lead to unintentional and uncoordinated movements. Treatment usually involves physical therapy or procedures that reduce nerve activity. In some cases, surgery may be needed to transfer nerves, or even muscles, to support facial movement.

If recovery from the injury is incomplete, patients may also experience continuous weakness in the muscles of the face. Solutions to this may involve a range of procedures from inserting small weights into the eyelids to transferring nerves or muscles. The resulting facial asymmetry can significantly impact social interactions and could have long-lasting effects on mental health, requiring careful attention from healthcare professionals.

Potential complications from a fracture in the temporal bone can include:

- Persistent hearing loss requiring hearing aids or cochlear implants

- Vestibular dysfunction causing long-term imbalance

- The growth of a cholesteatoma, a cystic mass, due to trapped epithelium in the middle ear

- Narrowing of the external auditory canal

- Meningitis due to the continuous leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

- Neurocognitive consequences and post-concussive syndrome following a closed head injury

Recovery from Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)

Just like any other serious head injury, getting proper rehabilitation is key to recovering from a temporal bone fracture. Some of the therapies patients might need include physical and occupational therapies, especially after a concussion. If the fracture leads to a balance disorder due to injury in the inner ear, vestibular rehabilitation might be necessary.

Furthermore, if the fracture results in hearing loss, patients will need care from hearing specialists. This could involve fitting hearing aids or managing cochlear implants, which are devices that help with hearing.

Doctors also monitor for leaks of cerebrospinal fluid – the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. Although these leaks don’t always need preventative antibiotics, they require close attention because they can increase the risk of serious infections like meningitis. Doctors should also watch out for the formation of cholesteatomas, which are abnormal skin growths that can occur in the middle ear due to the fracture.

In cases where patients experience facial paralysis from the fracture, and the normal function isn’t entirely restored, rehabilitation can help. Should the paralysis continue to be an issue in the long term, several approaches are available to regain function. These methods may include adding weights to the eyelids, lifting the eyebrow, or various procedures aimed at restoring movement to the face.

Preventing Facial Nerve Intratemporal Trauma (Injury to Face Nerves in the Skull)

The key piece of advice we can give to prevent fractures in the temporal bone (the area around the side of your head near your ear) is to always wear a helmet when you’re engaging in activities like cycling, skateboarding, skiing, rollerblading, snowboarding, horse riding, motorcycling, and driving all-terrain vehicles. A lot of research has proven that wearing a helmet significantly reduces the risk of skull fractures for folks who suffer head injuries while participating in assorted sports and industrial activities.