What is Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury)?

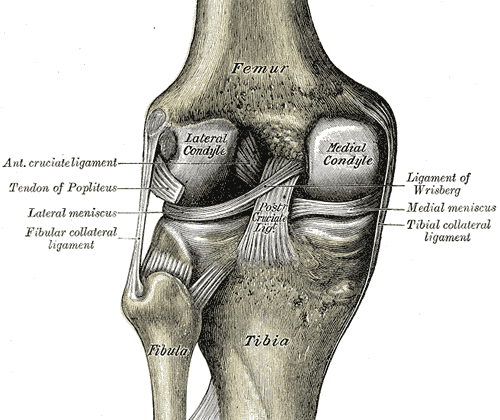

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a ligament in the knee that helps to keep it stable. It’s a tough band of connective tissue and collagen fibers that starts from the inner part of the knee joint (the intercondylar area of the tibial plateau) and stretches diagonally to attach to a part of the thigh bone (lateral femoral condyle). Here, it has two key points: The lateral intercondylar ridge and the bifurcate ridge, which separates the two parts, or bundles, of the ACL.

The ACL is about 32 mm long and 7 to 12 mm wide, and it’s made up of two parts: the anteromedial bundle and the posterolateral bundle. The anteromedial bundle is tougher when the knee is bent and mainly helps to control the forward movement of the shin bone (85% of the stability). The posterolateral bundle is tougher when the knee is straight, and its main job is to provide side-to-side and rotational stability (secondarily).

The ACL is strong, with a strength of 2200 N. Together with another ligament in the knee, the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), the ACL forms a cross (or an “x”) in the knee, stopping the shin bone from moving too far forward or backward compared to the thigh bone when the knee is bending or straightening. Mostly, the ACL is made of type I collagen (90%) and a bit of type III collagen (10%). It gets its blood supply mainly from the middle genicular artery, and is innervated by the posterior articular nerve, a branch of the tibial nerve.

What Causes Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury)?

Most athletes tear their Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) without being hit or touched, often by twisting or turning their knee in a wrong way. This usually happens when the shinbone moves forward while the knee is slightly bent and is pulled towards the outside. Athletes who participate in skiing, soccer, and basketball are more prone to suffer such injuries. For injuries caused by direct contact, like a hard hit, football players are more likely to be affected.

ACL tears can sometimes be associated with other injuries, both within (intra-articular) and outside (extra-articular) the knee joint. For instance, tears in the meniscus, the body’s shock absorber in the knee, can accompany ACL tears. In acute cases, the lateral meniscus is often injured, while the medial meniscus tends to be more affected in longer-term cases. Other knee ligaments, such as the PCL, LCL, and PLC, could also get injured along with the ACL. Over time, an untreated ACL tear can lead to more severe knee problems like damage to the cartilage and complex, non-repairable meniscus tears.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury)

The ACL, a ligament in the knee, is the most commonly injured part of the knee, accounting for around half of all knee injuries. This issue affects about 1 in 3500 people in the United States every year. Additionally, it leads to approximately 400,000 ACL reconstruction surgeries annually in the US. However, this data might not be fully accurate as there isn’t a standardized way to track these injuries.

ACL injuries occur across all ages and genders. But, there is a belief that women have a higher likelihood of injuring their ACL due to several factors. In the context of athletes, for every male athlete with an ACL injury, there are 4.5 female athletes with the same issue. Interestingly, female athletes tend to experience ACL ruptures at a younger age, and more commonly in the leg they use for support rather than the one they use for kicking, unlike males.

- Some studies have suggested that women may have a higher chance of ACL injury because their hamstrings are weaker, making them rely more on their quadriceps. This excessive use of the quadriceps when decelerating puts additional stress on the ACL, as these muscles are less capable of preventing anterior tibial translation compared to hamstring muscles.

- Additionally, women generally have less core stability than men, increasing their risk.

- The way women land may also contribute to a higher likelihood of ACL injuries, particularly if there is an increased valgus angulation and extension of the knee.

- In fact, females changing direction suddenly often place their knees in positions that stress the ACL. This, combined with decreased hip and knee flexion and decreased fatigue resistance, increases the risk.

There are other anatomical factors that could raise the risk of ACL injuries. These include having a higher body mass index, a smaller femoral notch, a smaller ACL, having hypermobile joints, joint laxity, or a previous ACL injury.

Sport-specific factors also impact ACL injury risk. For instance, soccer is associated with a higher risk of ACL injury in females, while basketball is linked to a higher risk in males.

Hormones can also influence ACL injury risk. The phase of the menstrual cycle before ovulation may impact coordination, and women on birth control pills seemed to be less affected by this. Some researchers believe that estrogen may affect the strength and flexibility of ligaments, potentially increasing injury risk in women, but this is still debated.

Interestingly, the production of collagen, linked to the COL5A1 gene, could be associated with a lower risk of injury in females.

Signs and Symptoms of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury)

An Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury, a common knee problem, often happens during sports activities. This can take place during sudden changes in direction, stopping or slowing down abruptly while running, or during an unusual landing after a jump. Key details such as how the injury occurred, the patient’s ability to walk, and how stable the joint is can all be helpful in diagnosing this injury.

Common symptoms include a sudden and painful “pop” in the knee, deep knee pain, and often immediate swelling caused by internal bleeding. About 70% of people with an ACL injury experience this kind of swelling. Other symptoms include the knee giving out, difficulty walking, and limited movement in the knee.

During a physical examination, the patient may show signs of avoiding bending the knee, known as a quadriceps avoidance gait. If the knee is not aligned correctly, this may signify a higher risk of another ACL injury. In such cases, a knee realignment surgery may be recommended when reconstructing the ACL.

Upon inspection, there may be swelling in the knee and tenderness along the joint line if there’s an associated meniscal injury. Depending on the other injuries present, the knee may also be locked.

To evaluate the condition of the ACL, several tests can be done. These include the anterior drawer, pivot shift, and Lachman tests.

- The Lachman test is the most reliable for assessing an ACL tear, with a 95% sensitivity and 94% specificity. It is performed with the knee flexed at about 30 degrees. The doctor will hold the lower thigh stable with one hand while pulling the shin bone forward with the other hand. Depending on how far the shin bone moves, an ACL tear can be graded from 1 to 3.

- The anterior drawer test is done with the knee bent at 90 degrees and checking the movement of the shin bone when pulled forward. This test is most effective in chronic injuries and not acute ones.

- With the pivot shift test, the shin bone is rotated inward while bending the knee. The shin bone might shift forward during the test if the ACL is damaged but this test is usually hard to perform if the patient is in pain or anxious.

- The lever sign test involves placing a fulcrum (like the examiner’s fist) under the upper part of the patient’s calf and applying downward pressure on the thigh. Depending on whether the ACL is intact, the patient’s heel will either rise off the examination couch or remain down.

- The KT-1000 test is performed with the knee slightly bent and rotated outwards to evaluate and measure anterior laxity.

It’s also crucial to check for potential associated injuries such as to the medial or lateral collateral ligament, the posterior collateral ligament, or to the menisci.

Testing for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury)

When suspecting an ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injury, the doctor may use an imaging technique called magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to confirm the diagnosis. MRI is the first choice in diagnosing these types of injuries, as it can accurately detect them 86% of the time and rule them out 95% of the time.

There are also methods like knee arthroscopy that can help tell the difference between complete and partial tears, and older versus newer tears. Arthrography, which is highly accurate for detecting ACL injuries, is not often the first choice for diagnosis because it’s an invasive procedure that needs anesthesia.

MRI is very effective at confirming an ACL injury and checking for any other related injuries. Healthy ACL fibers continue on a steeper path than the roof of the area between the knee joint bones (intercondylar roof). If there’s an ACL tear, there are primary and secondary signs that can be seen on an MRI.

For the primary signs, the MRI will show direct changes associated with the ligament injury. Doctors will look for swelling, an increased signal on certain types of images, a break or complete absence of the fibers, and a change in the path of the ACL. For instance, the ACL fibers might appear too flat compared to the intercondylar roof, which is often seen in cases where the ACL has scarred into another ligament, the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). Tears typically happen in the middle of the ligament, where changes in signal are most often seen.

Secondary signs show up as bone bruising in over half of ACL tears. Other secondary signs include an associated injury to the medial collateral ligament, a fracture on a part of the bone attached to the ACL, and a certain degree of forward movement of the shin bone relative to the thigh bone.

Apart from MRI, X-rays may also be useful to rule out fractures or other related bone injuries, or to show swelling in the joint. They may reveal conditions like a Segond fracture or an Arcuate fracture, both of which are types of fractures associated with ligament injuries.

Computed tomography (CT), though not typically used for assessing the ACL, can be useful when planning for revision surgery on the ACL, or for assessing bone loss in cases of tunnel widening and osteolysis.

Treatment Options for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury)

Treating an ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injury should be tailored to each individual’s specific needs. The treatment choices can include either surgery or non-surgical options, and the best choice depends on factors like the patient’s age, the level of activity they’re usually involved in, the sports they play, and the condition of other components that help in joint stabilization.

The first line of treatment for acute injury includes the ‘RICE’ method, short for Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation of the injured knee. To move around, the patient may need to use crutches or a wheelchair and should avoid putting weight on the affected knee. Pain relief can be achieved with over-the-counter medications such as NSAIDs or as advised by the doctor.

Non-surgical treatment may be considered for those with a less severe ACL injury and who are not involved in heavy physical activity or sports that require sharp turns or pivoting. Such patients are typically treated with physical therapy and adjustments in their lifestyle. Non-surgical methods may also be used in the case of partial ACL tears, which consist of an acute symptomatic treatment followed by 12 weeks of supervised physiotherapy, aiming at gaining back the full range of motion and gradually working to strengthen key muscle groups. However, non-surgical treatment does carry the risk of additional knee injuries due to repeated knee instability, especially in cases involving heavy manual work or sports requiring jumping or sudden changes in direction.

Surgery can either repair or reconstruct the torn ACL and is usually recommended in cases of severe damage in active younger or older individuals. The main goal of reconstructing the ACL is to restore the knee’s stability and reduce the risk of additional damage to knee cartilage or meniscus. Surgery is also an option for children, despite their active habits, and in cases of partial ACL tear with functional instability. The return to sports after surgery largely depends on various factors, including demographics, functional, and psychological aspects.

A repair in ACL treatment techniques has been observed recently, especially recommended for children, and the post-treatment results over 2 years show comparable results. In cases where the ACL reconstruction fails and instability persists affecting the individual’s activities, a revision of the ACL reconstruction is considered. However, the reason for the failure and any missed injuries should be determined first. Different graft options may also be considered in such cases, including quadriceps tendon, hamstrings, or allografts.

The selection of graft for ACL reconstruction widely varies and each comes with its pros and cons. Commonly used graft types include Quadrupled hamstring autograft, Bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) autograft, Quadriceps tendon autograft, and Allografts. Each graft type has its specific advantages and disadvantages regarding strength, healing speed, immunity, and infection risk.

The timing for ACL reconstruction depends on various factors and also on the status of associated injuries. Injuries relating to meniscal tears and Chondral injury are usually addressed during ACL reconstruction. Realignment osteotomy of the lower limb is also considered before or at the same time as ACL reconstruction. In pediatric cases, ACL injury and reconstruction timing is extremely crucial and needs careful consideration and planning.

What else can Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury) be?

When physicians assess knee injuries, they often have to take into consideration and rule out several conditions, due to their similar symptoms, such as:

- ACL tear (A ligament tear in the knee)

- Fracture of the femur or tibia at the growth plate (also known as Epiphyseal fracture)

- Injury to the medial collateral ligament in the knee

- Tear in the meniscus (a piece of cartilage that provides a cushion in the knee)

- Osteochondral fracture (damage to both the bone and cartilage in the knee)

- Dislocation of the kneecap (patella)

- Injury to the posterior cruciate ligament in the knee

- Fracture at the tibial spine (a small protrusion on the top of the shin bone)

It’s critical for doctors to weigh all these possibilities, perform the necessary examinations, and tests to ensure the right diagnosis is made.

What to expect with Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury)

Knees without a healthy ACL, or Anterior Cruciate Ligament, are more at risk of developing arthritis. This is especially true if there are additional injuries to the cartilage and meniscal structures. Restoring the ACL through reconstruction can help return the knee’s natural movement. It’s also noted that many people are able to return to their sports activities after this procedure.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury)

There are numerous complications that can occur during or after surgery. Topping the list is the graft tunnel mismatch. This happens when the graft is long enough to protrude from the tunnel that was made in the bone, which can lead to compromised distal fixation or the tibial bone plug becoming prominent. This kind of complication usually happens with certain types of grafts and techniques, but can be avoided by accurately measuring the tunnel and adjusting the graft to fit accurately.

Tunnel malpositioning, where the tunnel is not drilled in the correct position, can lead to a range of complications. On the femoral side, a vertical tunnel could result in persistent rotational instability. If the tunnel is misplaced anteriorly or posteriorly, it may cause a knee to be tight in flexion and loose in extension, and vice versa. On the tibial side, a tunnel misplaced too far upfront could cause a tight knee in flexion and roof impingement in extension. A tunnel misplaced posteriorly can lead to the ACL graft impinging on the PCL.

Additional complications include:

- Posterior wall blowout: This can be overcome by adequate posterior wall exposure and drilling the tunnel at the right angle.

- Graft failure: This can be due to various reasons like hardware failure, inadequate fixation, or a small graft diameter.

- Intraoperative graft contamination resulting in infection, which occurs in less than 1% of all cases and is mostly superficial.

- Stiffness and arthrofibrosis: This is the most common post-surgery complication where patients experience reduced patellar movement.

- Infrapatellar contracture syndrome: This can cause postoperative stiffness and reduced patellar movement.

- Patella Tendon Rupture

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

- Patella fracture: It usually happens 8 to 12 weeks postoperatively.

- Tunnel osteolysis: It’s a condition within the bony tunnel, created for the graft during surgery, begins to break down and is usually managed by observation.

- Osteoarthritis in the long term: It is often related to damage to the knee’s cartilage (meniscal injuries) and is more common in patients above 50 years old at the time of surgery.

- Saphenous nerve irritation when harvesting the hamstring autograft.

- Cyclops lesion: It’s a mass of tissue that forms at the site of past knee injury or surgery which can affect range of motion and knee function.

Recovery from Anterior Cruciate Ligament Knee Injury (ACL Injury)

After surgery, patients are strongly advised to place as much weight on the affected region as they can handle to reduce knee pain. They should also try to extend the leg entirely, especially if there was a knee or kneecap injury beforehand. The concept of making a full recovery as soon as possible should be emphasized.

Early recovery exercises that don’t overstrain the graft should be done. Around three weeks after surgery, patients should start doing certain exercises to strengthen the leg muscles. These exercises could include static contractions of the hamstring at any angle, static or coupled contractions of the legs muscles, active knee movement (from 35-90 degrees) along with strengthening of the core and butt muscles. Close chain exercises, such as squats or leg-press, should be highlighted.

When patients start their rehabilitation, there should be a focus to avoid some exercises, like those that involve strengthening the quadriceps during the 15-30° phase, leg extensions that imitate the anterior drawer, and the Lachman maneuvers.

Returning to sports is a controversial issue with no hard and fast rules on when and what type of sport to return to following surgery. It used to be thought that patients shouldn’t return to sports earlier than nine months after surgery. However, the patient should be able to do specific sports-related activities and go through a series of function tests, such as hopping and jumping on one or both legs. Dynamic valgus, which increases the chance of tearing leg muscles, should be monitored.

There has been a higher rate of repeated injuries reported for patients who return to sporting activities before they’re cleared to do so. This decision, ideally, should be made jointly by the surgeon and the patient.

For the prevention of injuries, distinct factors can be considered, especially for female athletes. These can include: training that targets neuromuscular improvement, jumping training, practicing jumping and landing with less valgus and more knee bending, and strengthening the hamstring to reduce the dominance of the quadriceps.

Advanced Post-Surgery Rehabilitation Updates

Several studies have assessed the impact of using neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) after surgery. The results indicated significant improvement in quadriceps strength in the first 4 to 12 weeks after the operation when 2 to 6 sessions of NMES were added to the standard rehabilitation plan each week.

There was no significant difference noted between Open Kinetic Chain Exercises and other strategies in terms of knee laxity, muscle strength, and self-reported function, regardless of the graft type used. It was also found that there was no difference when Open Kinetic Chain Exercises were started early (less than 4 weeks) vs late (12 weeks) post-surgery.

No clear advantage was found for in-person rehabilitation over home-based rehabilitation for strengthening leg muscles, knee laxity, and functionality, both short-term and long-term after surgery. The use of knee braces after surgery was also noted to not provide significant advantages in terms of knee laxity and physical function.

It was found that pre-surgery rehabilitation involving muscle strengthening and neuromuscular stability exercises for 3-6 weeks could enhance self-reported function and physical ability three months post-surgery. However, it was not reported to affect the return to sports.

Employing cold compression devices in the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery was found to help reduce pain and limit the need for pain medication compared to not using it.

Post-surgery, there are variable or low levels of evidence supporting the usage of psychological interventions, whole body vibration, protein-based supplement use to strengthen quadriceps, blood flow restriction training to enhance quadriceps size and muscle mass, neuromuscular control exercises, and passive motion.