What is Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury?

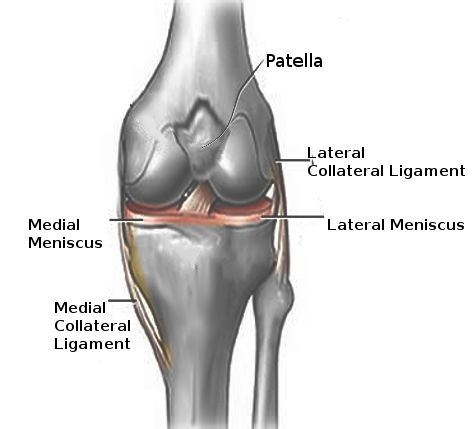

The Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL), also known as the fibular ligament, plays a crucial role in keeping the knee stable. It’s a strong, rope-like structure that attaches the thigh bone to the outer part of the lower leg, or fibula (see the picture titled ‘Left Knee Ligaments’). Along with a few other structures like the tendon of the biceps femoris muscle, popliteofibular, fabellofibular, and arcuate ligaments, the LCL is part of the “posterolateral corner” (PLC) of the knee, an region which may look slightly different in different people. The LCL’s main function is to prevent the knee from bending outwards excessively and rotating backwards. Although injuries to the LCL and PLC are less common compared to other knee injuries, doctors still need to be on the lookout for them during knee examinations.

The LCL begins from a part of the femur, or thigh bone, that is 1.4 mm above and 3.1 mm behind a knob-like structure on the outer side of femur. It then attaches to the fibula, 28.4 mm below the pointed part of the fibula, almost covering 38% of the fibular head. The LCL is supplied by the popliteal artery, a main blood vessel at the back of the knee, mainly through the anterior tibial recurrent arteries and branches of the superior and inferior lateral genicular arteries.

Unlike the Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) which spreads out like a fan, the LCL is cord-like. In addition, the LCL does not attach to the meniscus (a cushion like structure between the bones of the knee) and the joint capsule (the covering of the knee joint), like the MCL does. The LCL is usually about 2 to 3 mm thick, 4 to 5 mm wide, and about 69.9 mm long on average.

Deep under the LCL lies the popliteus tendon, which starts about 18.5 mm ahead and below the LCL and is about 55 mm long on average. Superficial, or closer to the surface, to the LCL is the iliotibial band, a thick band of fibers that runs down the outer part of thigh and inserts on the outer part of the knee. However, the LCL is exposed on its lower part on the front and outer side, which is sometimes used as an area of surgical access.

The LCL is the main structure that prevents the knee from bending outwards in all degrees of knee bending, with several other structures acting as additional preventers of this outwards bending. The LCL, along with fabellofibular, popliteofibular, and arcuate ligaments, is the main structure that keeps the PLC steady. The LCL also prevents the knee from rotating backwards.

The LCL helps limit the ability of the tibia, or the shin bone, to rotate outwards and move backwards when the knee is bent between 0 and 30 degrees. As the knee bends past 60 degrees, the popliteofibular ligament becomes more important in preventing this outward rotation, with the LCL also contributing to a lesser degree.

Research suggests that the LCL and PLC structures have minimal role in stabilizing forward and backward movement of the tibia when the cruciate ligaments, major ligaments within the hollow of the knee, are torn.

collateral ligaments, and lateral and medial menisci.

What Causes Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury?

The most typical way to harm your lateral collateral ligament (LCL), which is a ligament on the outer side of your knee, is by a strong hit to the front-inside part of your knee. This usually happens when your knee is overly straightened or twisted outwards. LCL injuries can also happen without any contact, such as if your knee is excessively straightened or twisted outwards.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury

The Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) in the knee gets injured on its own in less than 2% of knee injury cases. But, it’s often damaged along with other parts of the knee in 7% to 16% of all knee ligament injuries. Among high school athletes, isolated LCL injuries are the second least common type of knee injury, occurring 7.9% of the time. Injuries to the Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) are even less common, appearing in only 2.4% of cases. Contact sports result in 40% of combined Posterior Lateral Corner (PLC) and LCL injuries. Non-sporting accidents, like car crashes or falls can also cause damage to the LCL.

Certain factors may increase the risk of LCL injuries, based on limited research. These factors include being female, involvement in high-contact sports, and activities that require rapid turning and jumping. Soccer often leads to knee injuries in general, but tennis and gymnastics are more likely to cause isolated LCL injuries. A study done in the United States military also found that previous injuries to the knee, ankle, or hip can make someone more likely to injure the side of their knee (lateral knee injury).

- The LCL is injured alone in less than 2% of knee injury cases.

- It’s damaged with other structures in 7% to 16% of knee ligament injuries.

- Isolated LCL injury is the second least common knee injury in high school athletes, with an incidence of 7.9%

- Contact sports cause 40% of PLC and LCL injuries.

- Non-sporting accidents can also damage LCL.

- Being female, participation in high-contact sports and fast-turning and jumping activities may increase the chance of injury.

- Soccer often causes knee injuries, but tennis and gymnastics more specifically cause LCL injuries.

- Prior knee, ankle, or hip injury could lead to higher rate of lateral knee injury.

Signs and Symptoms of Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury

When patients come in with injuries, they often describe sudden pain on the side of the knee following a sharp blow or excessive, uncontrolled bending in the absence of contact. They might also talk about an abnormal walking style that involves their foot kicking outward while they’re mid-stride. Some people may experience numbness, weakness, or a sensation of “foot drop” on the side of their injury.

Doctors need a full medical history that captures a wide array of factors like disorders related to blood clotting, previous surgeries, type of work the patient does, their walking style, use of any devices for mobility, and circumstances around their living situation, like whether they need to climb stairs frequently at home.

The patient undergoes a comprehensive knee examination, which includes checking the full range of motion. Doctors commonly find tenderness on the side of the knee when they touch (palpate) it. Pain can also be felt in areas around the knee cap, specific growths on the bone (Gerdy’s tubercle), and where the knee cap attaches to the thigh bone. Changes in skin color (ecchymosis), swelling, and warmth can also be seen. The walk is analyzed for a characteristic “Varus thrust” finding.

Specific tests are done to pinpoint the area of damage and rule out other possible conditions. These further tests include:

- ‘Varus stress test’: The most effective in diagnosing ligament injuries on the side of the knee. This involves the clinician holding and maintaining the knee, while applying a bending force on the ankle at two different knee positions.

- ‘External rotation recurvatum test’: This checks rotation stability at the rear and sides of the knee. Here, the patient lies flat, and the clinician applies a downward pressure to the knee while lifting the big toe off the table and turning the shin bone outward.

- ‘Posterolateral drawer test’: The patient lies stomach down, knee bent at a right angle and turned outward slightly. The examiner grips parts of the knee bone and exerts a backward push on the knee to check for any excess sideways movement.

- ‘Reverse pivot shift’: Done in the same position as the posterolateral drawer test. The examiner holds the joint and gradually straightens the knee with a force that bends it sideways and turns it outward. A clicking sound indicates instability due to injury in multiple knee ligaments.

- ‘Dial test’: Useful in confirming side and rear knee injuries. The patient lies stomach down, while the examiner holds the thigh and turns the ankle and leg outward. It is done at two different knee bend positions. Any excess outward rotation on one leg confirms the injury.

In all knee examinations, it’s important to ensure they cover all structures of the joint in order to not miss other potential injuries to ligaments, knee pads, or other soft tissues, especially in cases of trauma. The examiner should apply the ‘Anterior and posterior drawer tests’ to rule out injuries to knee ligaments. The knee cap should also be assessed to detect shifting or dislodging.

Testing for Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury

If your doctor suspects that you have damaged your Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL), which is an essential ligament in your knee, they might want to run an X-ray. This won’t directly show any changes to the LCL, but it’s necessary for them to check for associated injuries. Often, these X-rays reveal things like fractures or avulsions (tearing away) of the fibular head, tibial spine, and lateral tibial plateau, which are parts of your leg and knee. Some specific signs on an X-ray, such as the arcuate sign and Segond fracture, directly point towards an injury to the posterolateral corner (PLC) of your knee, which means the LCL might be affected too. X-rays are also useful for ruling out arthritis in older patients who have chronic knee pain.

Your doctor may also perform Varus (forcing the knee into an unnaturally bent position) and kneeling posterior-stress radiographs (a type of X-ray), both of which can show the severity of the LCL and PLC injury.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is considered the “golden standard” for diagnosing structural LCL and PLC injuries, as it provides a detailed view of your tissue. Coronal and sagittal T1- and T2-weighted series, specific types of imaging used in MRI, have the highest accuracy for the detection of LCL injuries. But, even though MRIs are incredibly useful, they alone can’t decide the need for surgery. Your doctor will still perform physical examinations and review the X-ray.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound, another imaging technique, can help quickly identify LCL injuries. Signs of damage include thickening of the LCL and hypoechogenicity (under the ultrasound, damaged parts appear darker than normal tissue). If there’s a complete tear, ultrasound may show swelling, laxity, or lack of continuity in LCL fiber.

Depending on the severity of the damage, LCL injuries are divided into three grades:

* A mild sprain, called Grade 1, shows localized lateral knee tenderness without any instability.

* A partial tear, Grade 2, causes severe localized pain and swelling on the side and back of the knee, and the ligament may be stretchier than usual by 5 to 10 mm.

* A complete tear, Grade 3, causes variable pain and swelling, and usually affects the PLC and nearby structures. People with this decay often show mechanical symptoms like reduced motion, and more than 10 mm of laxity.

The grade of an LCL injury is instrumental in determining the most suitable treatment plan.

Treatment Options for Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) tears, unlike medial collateral ligament (MCL) tears, can’t heal by themselves, so it’s often best to quickly consider surgery when these injuries happen. How serious the tear is and whether there are other injuries to the knee play a crucial role in deciding if surgery is necessary. If there are other injuries to the knee, early surgery tends to be the best way to go.

The initial treatment for an LCL tear involves resting the knee, putting on a compress, taking an anti-inflammatory medication to reduce swelling and pain, and applying ice to the injured area. However, don’t apply ice for more than 15 minutes at one time to avoid damaging the nerve that runs along the side of your leg.

Surgery isn’t always needed for treating LCL tears. If you have a minor tear (doctors call this grade 1 or 2) and your knee isn’t unstable, non-surgical treatment could work. This consists of staying off the knee, using crutches, and wearing a knee brace for three to six weeks. During this time, you can begin a rehabilitation program that includes gentle exercises. Getting back to sports can take about six to eight weeks. However, if left untreated, injuries to the area on the back outside part of the knee can lead to abnormal leg alignment, like bow-leggedness.

Studies have shown promising results with this method of treatment, including NFL athletes with severe (grade 3) LCL tears returning to the game fast. However, surgery is usually the standard treatment for most severe tears.

Surgery could be necessary if you have a severe LCL tear that happened less than two weeks ago and tore away from its usual attachment site, as long as an exact reduction is attainable. This is done by making an incision on the outside of the knee, identifying the torn LCL, and sewing it back together.

If two weeks have passed since the injury happened, if the tear is in the middle of the ligament, or if there is ongoing instability in the knee, surgical reconstruction is necessary. This also applies to severe tears where reformation isn’t possible due to extensive damage to the surrounding tissues. If you also have other knee injuries, these can be tackled in the same surgery.

There are different ways to perform LCL reconstruction, and it can be categorized into three types – isometric, nonanatomic, or anatomic. The specific type of injury, the patient’s activity levels and needs, and the surgeon’s expertise decide the best approach.

One method – isometric tenodesis – involves a knee incision and moving a certain tendon to a new position through a split in the tissue at the back of the knee. The way this procedure works is that the tendon gets tightened over a screw as the knee is gradually straightened. As the knee reaches full extension, the screw secured.

Another method involves using a donated patellar tendon (from the knee). The surgeon will create tunnels in the upper fibula (calf bone) and a part of the femur (thigh bone) and pass the graft through. The surgeon tensions the graft with the knee bent 20° to 30°, then secures the graft using a screw.

Lastly, the anatomic reconstruction method reinstates the normal biomechanics of the knee using a semitendinosus graft (part of the hamstring muscles located at the back of the thigh). The surgeon drills tunnels at the ligament’s usual attachment sites, and secures an elongated tendon-like structure into these tunnels using a screw. The graft performs the function of the injured ligament and allows the patient to return to their normal activities.

What else can Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury be?

If you experience an injury to the side of your knee, it may be due to a variety of reasons. Here are some possible causes that doctors should consider:

- ACL and PCL tears: These are sometimes mistaken for LCL injuries because they can cause similar symptoms, like swelling, sudden pain, and knee instability. Doctors can use certain tests to tell the difference between these injuries.

- Lateral meniscus tears: This is another condition often confused with an LCL tear, as it can cause swelling and pain on the side of the knee. A specific test called the McMurray test can help tell them apart.

- Popliteal injury: This is usually caused by overuse (tendonitis) and can cause pain behind the knee, especially when walking downhill. A special test known as the Garrick test can help identify whether the pain is due to a popliteal injury.

- Bone contusion: This type of deep bruise can feel a lot like an LCL tear. Doctors can press on the side of your knee or move your knee in certain ways to see if the pain is from a bone contusion.

- ITB Syndrome: This condition can cause chronic pain at the side of the knee. It can be distinguished from an LCL tear as the pain doesn’t get worse with certain movements of the knee.

A detailed physical examination and the appropriate scans or X-rays will help the doctors to correctly identify what’s causing your knee pain.

What to expect with Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury

The seriousness of an LCL (Lateral Collateral Ligament) injury determines whether it can be treated with or without surgery. LCL and PLC (Posterior Cruciate Ligament) injuries usually have a good outcome when they receive the right treatment. However, it’s important to note that recovery from severe injuries might take more than 4 months.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury

If Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) and Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PLC) injuries are not diagnosed, they can lead to long-lasting complications. The most commonly reported long-term issues are instability in the knee and chronic pain. Studies have found that around 35% of people with PLC injuries also experience peroneal nerve palsy. This is probably because the nerve is located very close to the LCL. As a result, patients can end up with conditions like foot drop, weakness in the lower limbs, and reduced feeling in the top and side of the foot.

Similarly, those who undergo surgery to correct these injuries can experience complications like irritation from the surgical hardware and stiffness.

Here is a summary of the potential complications:

- Knee instability

- Chronic pain

- Peroneal nerve palsy

- Foot drop

- Weakness in the lower extremities

- Decreased sensation in the foot

- Hardware irritation from surgery

- Stiffness after surgery

Recovery from Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury

Healing and protecting the ligaments are important for all types of ligament injuries. Different strategies are used based on the severity of the injury.

* For minor and moderate ligament injuries (Grades 1 and 2), it’s recommended to start moving the knee flexibly in the weeks right after the injury. This helps to avoid stiffness or tightness of the muscle. A type of brace called a hinged knee brace is usually removed around six weeks after getting injured. Once the brace is removed, physical therapy can begin. Patients can go back to playing sports once they can move the knee fully without any pain, and any looseness or tenderness on the side of the knee is gone. Generally, they can safely return to sports after about four weeks for a minor injury and 10 weeks for a moderate injury.

* For severe ligament injuries (Grade 3), patients are advised not to put any weight on the knee for six weeks after surgery. They also need to wear a device called a knee immobilizer during this time. It’s important to continue strengthening the large muscles at the front of the thigh (the quadriceps) throughout recovery, just like with minor and moderate injuries. However, patients should avoid strengthening the muscles at the back of the thigh (the hamstrings) for at least four months to avoid further injury. Therapy specifically designed for their sport may start after four months after surgery.

Overall, a structured and progressive rehabilitation program that fits with the patient’s needs and goals is necessary for a successful recovery after treating a ligament injury.

Preventing Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury

To prevent injuries to the ligament on the outer side of your knee, termed as the Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL), you’ll need to follow different strategies that make your knee more stable and less prone to injuries. Here are some steps you can take:

– You could participate in a fitness program that focuses on strengthening the muscles around your knee. When the muscles around your knee are strong, they support your knee better and make it more stable. This results in decreased chances of hurting your ligaments.

– Make sure to maintain flexibility and mobility in your legs to enhance the movement of your knees. This also helps avoid a situation where certain muscles are stronger than others, causing imbalance.

– Always warm-up before participating in sports or physical activities to prepare your muscles and joints.

– Follow the correct techniques when performing physical activities. Having the right form takes some pressure off your knees and its ligaments, which further reduces the risk of injury.

It’s also important to wear shoes appropriate to your activity as they provide stabilization to your feet and ankles. Likewise, using protective gear like knee supports and braces, especially during high-risk activities or sports, can provide additional support to your knee. It’s also important to avoid risky behaviors that increase chances of injuring your muscles and bones.

By following these suggestions, you can considerably decrease your chances of getting LCL injuries.