What is Lumbar Disc Herniation?

Lower back pain is a widespread problem, affecting roughly 80% of people at some point in their lives. In the United States alone, this condition costs more than $100 billion each year. The most commonly diagnosed causes of lower back pain are degenerative disc disease and lumbar disc herniation. This is a condition where the spinal discs in the lower back get damaged. About 95% of these disc damages occur between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae or between the fifth lumbar and the first sacral vertebrae.

The lumbar region of the spine consists of five vertebral bones and the discs which sit in between them. This gives the lower back a curved shape. The spinal cord runs through these vertebrae, and nerves branch out from it through gaps formed by the connected vertebrae and discs.

The discs themselves are made up of a central section and a ring around it. The central part, called the nucleus pulposus, is like a gel and is composed mostly of water, along with some special proteins called collagen and proteoglycans. These proteoglycans attract and hold water, maintaining the disc’s height and allowing it to act as a cushion.

The outer section of the disc, the annulus fibrosus, rings around the nucleus pulposus. It’s made up of layered fibrous tissue containing collagen, proteoglycans, proteins, and elastic fibers. This fibrous ring gives the disc its strength and flexibility, and the ratio of collagen type varies from the inside to the outside of the ring. Together, all these components help keep our spine flexible yet strong.

What Causes Lumbar Disc Herniation?

When discussing disc degeneration, it is often linked to a condition known as disc herniation. As we age, the cells in our spinal discs, known as fibrochondrocytes, start to age and become resistant to renew themselves. This aging process also results in the decreased production of proteoglycans, molecules that help the discs stay flexible and hydrated.

This decrease leads to the discs losing water and eventually collapsing. This puts extra pressure on the annulus fibrosus, the outer layer of the disc, causing it to tear or develop cracks. Ultimately, this process can result in the inner substance of the disc, the nucleus pulposus, bulging out, a condition known as disc herniation.

Hence, when the spinal discs are subjected to repetitive stress, symptoms gradually develop and tend to become chronic, or long-term.

Conversely, a massive force or pressure on a healthy disc, known as axial overloading, can also cause the disc material to be forced out through a weakening annulus fibrosus. Injuries of this sort usually result in severe symptoms that manifest quickly.

Other less frequent causes of disc herniation include connective tissue diseases and inborn disorders like having short pedicles, the structures that connect the front and back parts of the spinal bones.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Lumbar Disc Herniation

Lumbar disc herniation, also known as LDH, is a condition that quite a few people deal with, having anywhere from 5 to 20 cases per 1,000 adults every year. It is most often seen in people in their 30s to 50s. Men are twice as likely to have LDH as compared to women.

Signs and Symptoms of Lumbar Disc Herniation

If a patient is suspected to have a herniated disc in their lower back, some signs and symptoms include:

- Radiating pain

- Lower back pain

- Sensory problems in the lower back and leg areas

- Muscle weakness in the lower back and leg areas

- Difficulty bending over

- Pain worsens with coughing, sneezing, or straining

- Increased pain when seated as it puts extra pressure on the nerve root

The patient’s pain history and lifestyle impacts are important to know, as well as any past or present treatments. They should also be asked about any history of problems in the urinary or bowel systems, changes in feeling in the lower body, previous illnesses or health conditions, and any use of drugs. There are some major warning signs that could indicate other serious conditions, such as fever, night sweats, unexplained weight loss, loss of appetite, severe pain, and tenderness in the spine.

Knowing the anatomy of the nerve roots and lumbar disc herniations is essential for interpreting the clinical findings. Radiculopathy varies based on the type and location of the herniation. For example, a herniation on the side at the 4th and 5th lumbar spinal bones would likely cause symptoms in line with the 5th lumbar spinal nerve root.

The 1st lumbar spinal nerve root, which exits the body between the 1st and 2nd lumbar spinal bones, can cause pain or sensory loss in the groin. The 2nd and 3rd lumbar spinal nerve roots can worsen symptoms when a person sneezes, coughs, or straightens the leg. The 4th Lumbar spinal nerve root, assessed with the patellar reflex, can cause back pain radiating into the front upper leg and inner aspect of the lower leg, along with sensory loss, and weakness in hip movement and leg straightening.

The 5th lumbar spinal nerve root which exits the body at the junction of the 5th lumbar and 1st sacral spinal bones can cause back pain that travels to the lateral aspect of the thigh and calf, and the top of the foot and big toe. Sensory loss occurs on the outer side of the calf and the top of the foot. There are pains at the inner leg and foot muscles, causing difficulty in walking on heels. This condition may also lead to muscle shrinkage if it becomes chronic.

The 1st sacral spinal nerve root, which exits the body between the 1st and 2nd sacral bones, can cause pain around the hip or buttocks that radiates down the side or back of the thigh, the calf, and the lateral or bottom of the foot. Sensory loss may be apparent on the lateral or bottom of the foot and they can experience weakness when trying to move the foot away from the center line of the body. This can lead to problems with walking on tiptoes and may affect bladder and bowel control and sexual function.

The straight leg raise test is a common way doctors evaluate patients with lower back pain. This test measures if the patient’s pain is reproduced when their leg is raised while laying flat on a table. Other tests include the crossed straight leg test, which is carried out on the non-painful leg. This test is positive when pain is felt in the painful leg when the non-painful leg is raised. This may indicate a central disc herniation with severe nerve root irritation.

A recent analysis suggested that a doctor could diagnose lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy through a straight leg raise screening test if three out of four findings are positive: 1) dermatomal pain aligned with nerve root distribution, 2) sensory deficit, 3) reflex abnormality, and 4) muscle weakness.

Testing for Lumbar Disc Herniation

Many people who have a herniated disc experience relief from symptoms naturally within 6 to 12 weeks, without needing any treatment. Some patients may even start to feel better sooner, particularly if they do not experience symptoms such as radiculopathy- a condition that causes pain, weakness, or loss of sensation in one part of the body. Therefore, it’s usually recommended to avoid imaging studies like X-rays or scans during this period, as their results are unlikely to change the course of treatment.

However, if a serious health problem underlying the herniated disc is suspected, or if there is a risk of nerve damage, further tests and imaging may be necessary. Imaging and blood tests may be ordered if a patient’s symptoms are severe, or if conservative treatment has not helped to improve symptoms after two to three months.

Blood tests like the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate and C-reactive protein, which identify inflammation in the body, may be conducted if a long-term inflammatory condition or infection is suspected. A complete blood count test may also be carried out if an infection or cancer is suspected.

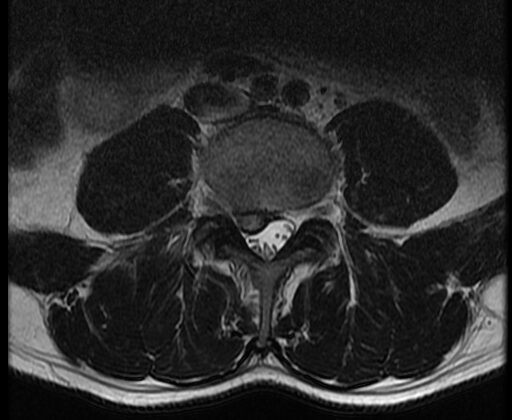

Lumbar X-ray films are typically the first option for imaging of the lower back. These X-rays can show the alignment of the spine, detect fractures, and find signs of wear and tear or degenerative changes in the spine. If the X-ray shows an acute fracture, a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be required for further investigation.

A CT scan is the best way to examine the bones of the spine. It can show a herniated disc that has calcified or bone destruction from the disease. However, CT scans are not good at showing nerve roots, which makes them less suitable for diagnosing radiculopathy. If an MRI cannot be performed, CT myelography, which involves injecting a contrast dye, is preferred. This test can provide an image of a herniated disc, but it must be carried out by a trained radiologist due to its invasiveness and associated risks like post-spinal headache, infection of the meninges (the protective membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord) and radiation exposure.

An MRI is considered to be the best test for confirming a suspected Lumbar Disc Herniation (LDH). It can provide a detailed view of the herniated disc due to its strong ability to visualize soft tissues and has 97 % accuracy in diagnosing LDH. The use of contrast in MRI improves the identification of post-surgical LDH. MRI is more effective than CT in deciphering inflammatory, malignant, or infectious causes of LDH. In situations where LDH is highly suspected but the MRI didn’t show clear results, nerve conduction studies (tests to measure how well and how fast the nerves can send electrical signals) may be needed.

In special circumstances, there’s a type of MRI sequence called Diffusion tensor imaging used for detecting minute changes in the nerve root. This could aid doctors in understanding the changes that occur after a herniated lumbar disc squeezes a nerve root. Consequently, helping to decide if patients require surgical intervention.

Treatment Options for Lumbar Disc Herniation

Most symptoms of Lumbar Disc Herniation (LDH), a condition where a disc in the lower back becomes damaged and bulges into the spinal canal, often go away on their own within six to eight weeks. Therefore, doctors typically first treat it conservatively unless there are serious, urgent symptoms such as a progressing nerve problem or cauda equina syndrome (severe low back pain due to a prolapsed lumbar disc). Recent comparisons of conservative and surgical treatment showed similar results over time. However, some studies have reported quicker relief and better quality of life with surgery. The decision for non-emergency LDH treatment is made based on a discussion between the doctor and patient, considering their condition, the duration of their symptoms, and the patient’s preferences.

The go-to treatment for patients with symptoms of acute LDH is typically conservative management. General practitioners may recommend a short period of rest, educate the patient about the condition, recommend physical exercises and prescribe pain relief medications and physical therapy. Generally, the symptoms start to improve over a couple of weeks. Physical therapy is usually not recommended before three weeks from the start of symptoms. Moderate non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are initial pain management options. If these do not provide relief, opioid medications may be considered, but with caution due to their side effects—something that needs to be discussed with the patient. If symptoms persist beyond six weeks, epidural steroid injections might be taken into account for short-term pain relief. This conservative treatment approach usually helps in most LDH cases that do not require surgery.

Surgery is considered the last option, reserved for when LDH-induced nerve pain persists despite conservative treatment. Nearly 180,000 to 200,000 surgeries for this cause are performed in the United States yearly. Having surgery earlier (within six months to a year) rather than later in patients where the symptoms necessitate it, is associated with faster recovery and better outcomes in the long run.

There are several versions of the surgical treatment, including an open approach and a minimal-invasive approach. The open approach is known as an open microsurgical discectomy, and the minimal-invasive approach involves less invasive procedures such as small incisions under endoscopic or microscopic guidance. The surgical team selects the strategy based on the specific location and characteristics of the herniated disc. Minimally invasive surgeries typically lead to shorter surgery time, less blood loss, and comparable complications, reoperation rates, or wound infections as compared to open surgeries. However, in the long term, both open and minimally invasive surgeries yield similar patient-centered outcomes.

While total lumbar disc replacement has been used as an alternative to lumbar fusion for degenerative disc disease, its use in lumbar disc herniation hasn’t been as popular since it provides no advantage over the open or minimally invasive approaches.

What else can Lumbar Disc Herniation be?

There are many possible causes of back pain, including:

- Mechanical back pain, which is discomfort caused by the movement or posture of the spine

- Muscle strains, where muscles are stretched too far and tear

- Osteophytes, essentially bone spurs that can cause discomfort

- Spondylolisthesis, a spine condition where one vertebra slips forward over the one below it

- Degenerative spinal stenosis, a narrowing of spaces within the spine that can put pressure on the nerves

- Cauda equina syndrome, a rare disorder that affects the bundle of nerve roots at the lower end of the spinal cord

- Epidural abscess, an accumulation of pus between the outer covering of the spinal cord and the spine

- Epidural hematoma, a condition where blood gathers between the outer cover of the brain and skull

- Diabetic amyotrophy, a nerve disorder related to diabetes that mainly affects the thighs, hips, buttocks and legs

- Metastasis, the spread of cancer to the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis, a type of arthritis that particularly affects the spine

- Synovial cysts, fluid-filled sacs that can cause spinal nerve compression

- Neurinoma, a type of tumor in the nervous system

What to expect with Lumbar Disc Herniation

Lumbar disc herniations, or slipped discs in the lower back, usually get better by themselves, with 85 to 90% of people recovering within 6 to 12 weeks. This usually happens without the need for extensive medical treatment. However, if the symptoms persist for more than six weeks, it’s less likely that they would get better on their own. In fact, patients who don’t experience pain along the nerves, known as radiculopathy, usually improve even faster.

Improvement comes about as the body naturally ‘cleans up’ the slipped disc material and reduces the swelling in the nerves, which reduces the pain and helps restore normal functionality. This also happens if the slipped disc material is hydrated, or when the swelling around the nerves decreases.

There are a few factors that indicate a high chance of successful recovery after surgery. These include intense pain in the leg and lower back before the surgery, shorter time period of symptoms, younger age, good mental health status, and regular physical activity prior to the surgery. Conservative medical treatments are equivalent to surgical interventions in the long term. However, surgical methods often provide quicker relief from painful symptoms and can enable a faster return to normal function.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Lumbar Disc Herniation

One of the main issues that can arise from Lumbar Disc Herniation (LDH) is chronic back pain. If not appropriately treated, patients with severe nerve root compression can end up with permanent nerve damage and chronic neuropathic pain. There are also risks involved with treatments like surgical interventions or epidural steroid injections.

Potential complications from these treatments could include:

Epidural steroid injections:

- Nerve damage

- Dural puncture which can cause headaches

- Chance of infection

- Epidural abscess – a localized infection in the space around the spinal cord

- Epidural hematoma – a blood clot in the space around the spinal cord

- Paralysis, although this is very rare

Surgical intervention:

- Decline in functional wellbeing

- Dural tear – a tear in the covering of the spinal cord

- Post-surgery infection

- Damage to the nerve root

- Reoccurrence of disc herniation

- Injury to the large vessels such as the aorta and vena cava, due to perforation of the anterior longitudinal ligament

- Epidural fibrosis – a condition where scar tissue forms near the nerve root

Preventing Lumbar Disc Herniation

Over 85% of people with symptoms of an acute herniated disc, which means a disc in the spine that has been suddenly damaged or displaced, usually see their symptoms ease within 6 to 12 weeks even without any treatments. Those not experiencing radiculopathy, a condition where a nerve or nerves along the spine are compressed, usually recover faster.

It is recommended that these patients take some time to rest and be free of their usual daily activities. If the pain persists, the consultation of a physical therapist may be necessary.

If patients start to notice signs of cauda equina, which is a serious neurological condition affecting the bundle of nerve roots at the lower end of the spinal cord, they should seek immediate medical attention. The rate of recovery and future health condition will largely depend on how quickly treatment is administered from the time symptoms first appear.

Research has found that both conservative management strategies like lifestyle changes and physical therapy, and surgical treatment have similar outcomes two years after treatment. However, surgical treatment usually provides quicker relief from pain.