What is Lumbar Spinal Stenosis?

The spine, or backbone, is made up of two parts: the front (anterior) and the back (posterior). The front of the spine is made up of roundish bone segments, called vertebrae, which are separated by discs that act as cushions between them. These discs have a soft, gel-like center, wrapped in a tougher ring of cartilage. The discs are biggest in our neck (cervical) and lower back (lumbar) areas, helping these parts of the spine move easily. The primary function of the front part of the spine is to absorb shocks during our movements.

The back part of the spine is made up of bony arches and protrusions. Each vertebra has a bony arch with two pairs of outgrowths at the front and the back. Other structures include side (lateral) and back (posterior) protrusions, and two pairs of joint surfaces (facets) on the top and bottom. These facets help form the facet joints. The spinal cord, which is our body’s main information highway, runs through a channel created by the front and back parts of the spine. Nerve roots, the parts of nerves that leave the spinal cord, exit above each vertebra through openings called intervertebral canals. The ligamentum flavum, a thick fibrous structure, bridges the space between two adjacent vertebrae at the back.

There are potential areas called lateral recesses in the back part of the spine. These narrow spaces can put pressure on the nerve roots, leading to discomfort or pain. The main roles of the back part of the spine include protecting the spinal cord and nerve roots, and providing a platform for muscles and ligaments to attach.

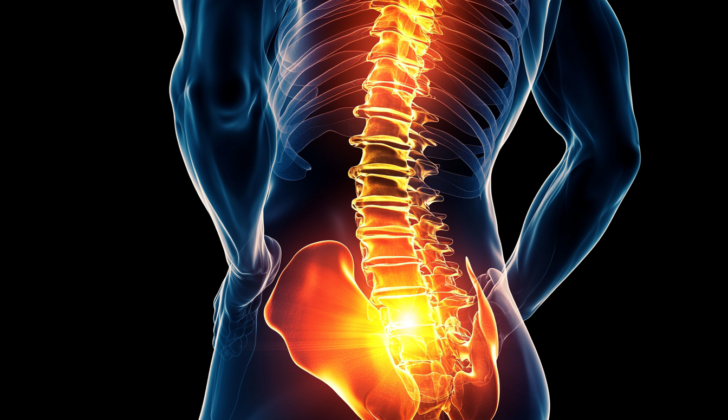

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a condition marked by the narrowing of the canal in the lower back, or lumbar, area of the spine. This narrowing can happen in the central canal, the lateral recesses, or the openings through which nerves leave the spinal cord (neural foramen). This puts pressure on either the spinal cord or the nerves, leading to symptoms that may be felt on one or both sides of the body.

The central canal narrowing comes from an enlarged ligamentum flavum along with bulging discs, and is most commonly seen between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae. The narrowing in the lateral recesses happens due to joint disease and bony outgrowths, or osteophytes, pressing on the nerves before they exit the spinal column. The narrowing in the neural foramen is due to a loss of disc height, disc protrusion, or osteophytes affecting the nerve root within the foramen itself. Extraforaminal stenosis usually happens due to a disc bulging outwards, putting pressure on the nerve root after it exits sideways through the foramen.

LSS is a significant cause of disability in older adults, and is a common reason for spinal surgery in people over 65. The condition can be difficult to define and diagnose, because there are no universally accepted criteria despite its widespread occurrence.

What Causes Lumbar Spinal Stenosis?

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) can be something you’re born with or it can develop over time. The most common cause of this condition is due to wear and tear that affects the spine as you age, known as degenerative spondylosis. Getting older, constant wear on the spine, and physical injuries are the main factors that can lead to this.

When the rubbery discs, present between each of your spinal bones, start to degenerate, they can bulge backward and place more pressure on the back part of your spinal bones. This pressure can cause overgrowth of bones (osteophytes), joint swelling, fluid-filled sacs in the joints (synovial facet cysts), and a thickening of a key ligament in your spine (ligamentum flavum). These changes all contribute to LSS.

Another cause of LSS is when one of the bones of the spine slips forward over the one below it. This condition, known as degenerative spondylolisthesis, typically happens in the lower part of the spine, most commonly in the region joining the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae. When this happens, it can narrow the space for the spinal cord and cause stenosis.

There are also other, less common conditions that can cause LSS. These include tumors or other growths, development of scar tissue after surgery, rheumatic diseases, and bone disorders like ankylosing spondylitis and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. On rare occasions, LSS can be a result of genetic conditions like achondroplasia, which can cause abnormally small spinal bones and poorly oriented joints.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Understanding how many people suffer from Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (LSS) is challenging due to a lack of a universally agreed upon definition. However, various studies have attempted to understand how prevalent this condition is. A study conducted in Framingham found that nearly 20% of participants aged 60 to 69 had a spinal canal less than 10 mm in diameter. A Japanese study noted an increase of LSS symptoms with age, observing it in 1.9% of 40 to 49 year olds, 4.8% of 50 to 59 year olds, 5.5% of 60 to 69 year olds, and in 10.8% of those aged 70 to 79. In comparison, LSS is reported to affect over 200,000 individuals in the US. It’s the most common reason people older than 65 undergo spinal surgery.

Genetic factors may make some individuals more likely to develop LSS. These faulty genes may encourage the growth of bone spurs in the spinal vertebrae and facet joints, thickening of a spinal ligament, and degradation of the spine’s intervertebral disks.

For people over 40, nearly 80% may harbor moderate signs of LSS and 40% may show severe signs, according to radiological examinations. In the United States, about 11% of the elderly population have signs of LSS on their radiological tests, and 20% of people over the age of 60. Interestingly, 80% of these individuals do not display symptoms. LSS contributed significantly to spinal surgeries in the US: Within a year of diagnosing lumbar degeneration, 5.9 out of every 100 patients had a lumbar fusion procedure.

- About 20% of those aged between 60 to 69 might have LSS, based on a Framingham study.

- A Japanese study noted an increase in LSS symptoms across age groups:

- 1.9% aged 40 to 49.

- 4.8% aged 50 to 59.

- 5.5% aged 60 to 69.

- 10.8% aged 70 to 79.

- Over 200,000 individuals in the US are affected by LSS.

- It’s the top reason for spinal surgery in people over 65.

- Genetic factors could play a part in developing LSS.

- Radiological tests show moderate LSS in 80% and severe in 40% of people over 40.

- About 11% of the elderly in the US show radiological signs of LSS, and 20% of those aged 60 and above.

- Surprisingly, 80% show no symptoms.

- After being diagnosed with lumbar degeneration, 5.9 out of every 100 patients undergo lumbar fusion within a year.

Signs and Symptoms of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) often shows up as lower back pain, leg pain, or difficulty walking that gets worse with movement and extending the lower back. This discomfort is usually felt on both sides of the body, although it might be stronger on one side. People suffering from LSS often feel numbness or tingling in their legs, and about 43% of those affected may also experience weakness.

When suffering from LSS, some patients may find that walking upstairs is easier than walking downstairs, as leaning forward while climbing can help ease the back pain. This phenomenon is also known as the “shopping cart sign”, where assuming a posture as if pushing a shopping cart relieves the discomfort. There’s also the “simian stance”, where walking with a slight bending of the body and knees can help alleviate the pain.

The symptoms can vary depending on the type and severity of the stenosis. Mild LSS often presents no symptoms. However, moderate LSS can cause a reduction in the spine’s central canal or nerve root canal, leading to an inability to sit without pain for a prolonged period and walking difficulties. In severe cases, sufferers may present with muscle weakness, abnormalities in gait and posture.

It’s important to note that LSS can progress to more serious conditions, such as cauda equina or conus medullaris syndrome. These involve symptoms like new-onset bowel or bladder dysfunction, saddle anesthesia, and increased weakness in the lower extremities. Such conditions require immediate medical assistance.

For diagnosis, a thorough physical examination is mandatory, with special attention being paid to any neurological signs. In some cases, a physical examination may show nothing unusual, particularly in people with mild or asymptomatic LSS. Some physical tests and clinical questionnaires may be used to evaluate the disease’s impact on patient’s function and quality of life.

- Lower back pain

- Leg pain

- Difficulty walking

- Numbness or tingling in the legs

- Muscle weakness

- Walking difficulties

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction

- Saddle anesthesia

- Increased weakness in the lower extremities

Testing for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Having a clear definition and set diagnostic criteria for lower back pain due to lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is somewhat challenging. But when back pain is partnered with certain risky symptoms and there is a suspicion of LSS, imaging techniques can help with diagnosis.

Simple x-ray imaging can be very valuable in checking how weight-bearing actions affect the stability of the spine. Sometimes with LSS, you will see changes like the growth of bone spurs and the reduction in the height of the cushioning disks between the spinal bones. An x-ray can predict if you have LSS by measuring the size of the space between the bones in the lower spine. Furthermore, dynamic or moving images can help verify if there’s any shifting position of the spine that might require surgery.

Computed tomography (CT) scans can give a cross-sectional view of the spinal canals. If these spinal sacs measure less than 75 mm2, it likely indicates complete LSS, while a measurement less than 100 mm2 suggests relative or possible LSS. CT scans can also check for lateral recess stenosis (another cause of lower back pain), and a measure of less than 4 mm often points to this condition. Computer-assisted imaging using deep learning algorithms, like LSS-VGG16, is a valuable tool in diagnosing LSS and predicts it correctly almost 90% of the time.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan without contrast is the preferred method for checking for LSS since it can identify any nerve damage in the region better than a CT scan. However, if you’re unable to have an MRI scan, then CT myelography can be used as an acceptable substitute.

Many experts consider less than 76 mm2 for severe stenosis and less than 100 mm2 for moderate stenosis as indicative of LSS. MRIs can also look for a “nerve root sedimentation” sign, which is a good indicator of LSS. Differentgradingsystems based on MRI scans such as Schizas, Braz, and Lee’s grading systems can help provide diagnostic accuracy and guide the decision as to whether surgery is necessary.

In addition, a more advanced type of MRI scan – the axial loading MRI – is better at checking for LSS. Regular MRIs can overestimate the size of the lateral recess (the gap between every two spinal bones) by nearly 13%. Machine learning can help to effectively estimate the dimensions of the lumbar canal, and deep learning methods have been successfully used for MRI studies to check spinal canal narrowing and joint arthritis in the spine.

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies could also help verify if you have LSS by helping rule out other conditions that can look similar. These tests can also check how well your muscles and nerves are working in the affected region.

Treatment Options for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

The goal of managing Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (LSS), a condition where the spinal canal narrows and compresses the nerves, is to reduce pain and improve functionality. Treatment strategies may include pain medication, using a spinal brace for support, physical therapy, electronic stimulation of nerves (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation), adjusting nerve signals (neuromodulation), injections of anti-inflammatory steroids into the spine (epidural steroid injection), inserting a small device between the spine bones (interspinous spacer), and surgical procedures to relieve pressure on the spinal cord (surgical decompression).

Improving lifestyle habits can positively impact overall health. Medical strategies, like taking pain medication, can provide short-term relief from pain. However, there is currently a lack of clear guidelines and strong evidence supporting these strategies. Painkillers, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are usually the first choice for managing pain. Other options can include opioids, muscle relaxants, gabapentin, vitamin B12, and calcitonin. Hemp-derived cannabidiol could also help in reducing pain. However, the long-term use of these medications lacks supportive evidence.

Physical therapy has modest evidence to support its use in improving both pain and functionality six months after surgery. But, well-defined physical therapy routines are lacking. Exercises that strengthen and stretch the core muscles can help correct posture and alleviate symptoms.

The effectiveness of some strategies, like spinal bracing, electrical nerve stimulation, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation, is uncertain. They typically only provide short-term benefits. Steroid injections into the spine can provide significant pain relief; however, the relief generally lasts for between two weeks to six months.

Surgery is usually an elective choice unless there is a medical emergency, such as cauda equina syndrome, where the nerves at the end of the spinal cord are severely compressed. During surgery, the goal is to ease pressure on the spinal cord without compromising the stability of the spine. The most common type of surgery performed is a wide decompression (liberal laminectomy). However, successful results from surgical procedures tend to decrease over time.

The best methods for managing LSS largely depend on the patient’s specific symptoms, their functional limitations, and how they respond to interventions. Treatments should be tailored for each patient based on their individual circumstances.

What else can Lumbar Spinal Stenosis be?

When a doctor is considering a diagnosis of LSS (Lumbar Spinal Stenosis), they also need to think about a range of other conditions that could cause similar symptoms. These include:

- Vascular claudication: This condition often causes symptoms in both legs, pain while standing, and might show a ‘shopping cart sign’, where leaning on a shopping cart helps to relieve pain. Tests such as vascular imaging and checking the ankle-brachial index can confirm the diagnosis.

- Peripheral neuropathy: This nerve disorder often causes a stocking-and-glove type of pain that can also disturb sleep.

- Lumbar spondylosis: This condition can be identified through a positive straight leg or Lasègue test (L4 to S1) and reverse straight leg or Ely test (L2 to L4).

- Lumbar plexopathies: These conditions can cause sensory and motor deficits without any pain, depending on the cause.

- Hip or knee osteoarthritis: People with these conditions usually have pain and tenderness in the hip or knee area, often without any neurologic signs.

- Metabolic neuropathies: Examples include alcohol abuse disorder and vitamin deficiencies. These conditions might cause sensory and motor deficits and systemic signs, depending on the cause.

A careful examination can help tell these conditions apart from LSS.

What to expect with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS), a condition causing pain and disability in the lower back area, is a major health concern. Roughly half of these patients may experience symptoms in other parts of their back over time. Yet, in about 33% to 50% of mild to moderate cases of LSS, the body heals itself in the long term. This has been confirmed by the North American Spine Society, which reports nearly 50% of mild to moderate LSS patients experiencing symptom improvement.

Long term studies have shown that with non-surgical treatment, symptoms can worsen in 15% of cases in 5 years and nearly 30% in 10 years. In contrast, symptoms improved in 70% and 30% of patients in the same intervals. Generally, about 20-40% of people with mild to moderate LSS may need surgery within the next 10 years.

Situations where surgery is more likely include if one has the cauda equina syndrome, degenerative scoliosis, spondylolisthesis or ongoing severe symptoms. However, not all cases of severe LSS need surgery, especially if they don’t show symptoms. Therefore, relying too heavily on MR imaging to evaluate your condition isn’t recommended.

The preoperative Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), a measure of pain intensity, can predict recovery chances. Lumbar decompression surgery, commonly used for moderate-to-severe central canal stenosis, has been found to significantly improve VAS scores, indicating less pain post-op. Without surgery, up to 70% of patients might require multiple medications to manage their symptoms. This surgery greatly reduces the need for such medications.

Patients who undergo a type of surgery called microsurgical decompression usually experience improvements in their back’s shape and alignment for up to 5 years before it begins to worsen for about a third of patients.

If you’re considering surgery, note that conditions like preoperative depression, older age, concurrent depression, and being placed in a specialized rehabilitation unit can raise treatment costs. Instability is also more common in cases involving abnormal curving of the spine (spondylolisthesis) and fluid-filled sacs in the spine (facet cysts). However, stopping smoking and losing weight pre-surgery can greatly improve your outcome.

Selective microendoscopic laminotomy (MEL) — surgery targeting only problematic spinal levels — lowers the chance of needing further surgery in patients with multilevel spinal issues. Semirigid polyetheretherketone (PEEK) implants have been found to improve the spine’s movement, reduce complications and minimize degradation of adjacent vertebral segments. Standard surgical instruments yield good results such as pain relief and improved bone fusion, even in patients with weak and brittle bones (osteoporosis). If you have narrow spinal canals in both your neck and lower back, a two-stage decompression surgery is advised, while for neck and upper back stenosis, a one-stage decompression is recommended. You can expect more significant relief in leg pain than back pain post-surgery.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (LSS) can lead to a range of complications, including:

- Chronic back and lower limb pain

- Decreased ability to exercise

- Reduced movement and function

- Muscle shrinkage

- Feelings of depression and anxiety due to these symptoms

- Lowered quality of life

- Cauda equina or conus medullaris syndrome, which are serious conditions that affect the nerves in the lower part of the spine

There can also be problems related to open and less invasive treatments for LSS:

- Blood clot in the spine

- Tear in the outer layer of the spinal cord

- Infection at the surgical site

- Injuries to nerves or blood vessels caused by the surgery

- Items used to stop bleeding left in the body

- Instability in the spine

- New bone growth

- Failed back surgery syndrome, a chronic pain condition

- In rare cases, death can occur, reported in 0.5 to 2.3% of open laminectomy cases. Laminectomy is a surgical procedure to relieve pressure on the spinal cord or nerves

People should be advised to seek immediate medical help if they experience symptoms of LSS to allow for quick treatment and prevention of these complications.

Preventing Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS), narrowing of the spine often caused by aging, can be difficult to prevent completely. However, there are certain lifestyle choices you can make to help reduce your risk or slow its progression. These include:

- Regularly exercising to stay fit

- Practicing good body movements, like lifting heavy items with your knees rather than your back

- Taking regular breaks if you have to sit for a long time

- Wearing comfortable shoes

- Maintaining a good posture, like sitting and standing straight

- Using furniture and equipment designed to support your body’s natural position

- Avoiding smoking

- Drinking plenty of water to stay hydrated

- Stretching on a regular basis

We recommend yearly health check-ups and immediately consulting a healthcare professional if you experience lower back pain, especially if it’s accompanied by a loss of sensation or movement, or pain in your legs.

If you’re diagnosed with LSS, your treatment will be approached in a step-by-step manner. The first options explored will usually be less invasive treatments and strategies. Surgery will only be considered if less invasive treatments aren’t effective or if there are severe symptoms present. If surgery becomes necessary, strategies that are minimally invasive will be considered before more significant procedures. As part of your treatment, you’ll also learn about managing both physical and emotional aspects of pain, which is another important part of your overall care.