What is Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee?

Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee is a fairly uncommon health condition. It’s a type of bone damage that impacts a layer of bone just below the cartilage in your joints. This typically leads to knee problems and pain, and it’s common mostly in school-aged children and teenagers. Specifically, in osteochondritis dissecans, a chunk of bone and cartilage in your knee joint separates from the bone underneath. This detached fragment could be stable, meaning the cartilage on top is still intact, or unstable, which can have serious health consequences. This condition is mainly found in people aged 10 to 20 and is more common in boys than in girls. Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans occur in patients with growth plates that are still developing, while adult osteochondritis dissecans refers to patients who have reached full skeletal maturity.

Despite being known for over a hundred years, the exact reason why osteochondritis dissecans causes knee problems and pain is still not fully understood. Recently, the cause is thought to be a deteriorating bone lesion characterised by bone breakdown, caving in, and fragment formation. This was first proposed in 1887, suggesting inflammation as a contributing factor in the development of the condition. Despite no proven evidence of inflammation in studies of tissue samples, the term “osteochondritis” continues to be used for this condition.

People with this condition usually either come to doctors with knee pain, or these knee problems are identified by X-rays taken for other unrelated injuries. Doctors often rely on X-ray images to spot the condition, with an MRI scan used as the main tool for better understanding the extent of the condition. The lesions, or sores, typically occur in the lower thigh bone, usually on the side of the large, rounded, bony part of the thigh bone on the inside of the knee. Simple treatments for stable lesions include rest, anti-inflammatory medication, avoidance of physical activities that could make it worse, and physical therapy. Patients who have not fully matured skeletally, meaning their bones are still growing, often do well with this non-surgical treatment. On the other hand, adults with larger lesions or loose bodies within the joint may need surgery.

The crucial factor predicting the outcome is the patient’s skeletal age when symptoms first appear. Although more than half of children with osteochondritis dissecans usually get better through simple, non-surgical treatments within 6 to 18 months, adults often require surgery. If left untreated, people may experience long-term changes, chronic pain, as well as annoying symptoms like knee-locking and clicking sounds.

What Causes Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee?

The exact cause of osteochondritis dissecans, a joint condition, isn’t known. However, there are a few theories, such as repetitive small injuries, reduced blood flow to the area, and genetic factors. People who have extreme obesity or a high body mass index (BMI) are more likely to develop this condition.

There isn’t complete agreement among medical professionals about what causes this condition in the knee, but repeated injury is commonly thought to be the most usual cause. It’s thought that in adults, the condition might be due to some sort of injury to the blood vessels in the area.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee

Osteochondritis dissecans is a condition usually found in younger people, especially those aged between 12 and 19. The number of cases in this age group is 3.3 times higher than in adults between 20 to 45 years old. The condition affects about 9.5 to 29 in every 100,000 people. It is more common in males, who are 2 to 4 times likely to get it than females.

Most people with osteochondritis dissecans, about 75%, have it in their knee. Of these, 64% have it in part of their knee called the medial femoral condyle. Also, 32% of knee cases include the lateral condyle. Other parts of the knee, such as the trochlea, patella, and tibial plateau, can also have osteochondritis dissecans. Usually, the disease only affects one side, but between 7% to 25% of patients can have it in both knees.

- Osteochondritis dissecans often affects people aged 12 to 19.

- In this age group, incidence rates are 3.3 times higher than in adults aged 20 to 45.

- The condition affects around 9.5 to 29 out of every 100,000 people.

- Males are 2 to 4 times more likely to have the disease than females.

- About 75% of people with osteochondritis dissecans have it in their knee.

- Of these, 64% have it in part of the knee called the medial femoral condyle.

- 32% of knee cases are in the lateral condyle.

- The trochlea, patella, and tibial plateau can also be affected.

- The disease usually affects one side, but 7% to 25% of patients have it in both knees.

Signs and Symptoms of Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee

Osteochondritis dissecans is a condition that can cause knee pain, often mistaken for other common causes of knee discomfort. It’s characterized by a vague and often hard-to-identify knee pain, which gets worse with physical activity. As the condition progresses, patients may notice stiffness, occasional swelling after physical activity, and a “locking” or “catching” sensation in the knee—signs of advanced disease or the presence of loose cartilage inside the joint.

When evaluating a patient, healthcare professionals must look into the patient’s history such as past injuries, recent increase in physical activities, and presence of mechanical symptoms such as locking or catching. Also, they must note that about 80% of patients with this condition experience pain mostly during weight-bearing activities. In younger patients, the pain comes and goes and is often associated with physical activities, often localized to the front side of the joint. Meanwhile, adults are more likely to experience swelling and limited motion in the knee or further mechanical symptoms such as catching or locking.

In physical examination, two elements are usually considered:

- Inspection: By examining the alignment of the knee, a healthcare professional could discover changes indicative of osteochondritis dissecan, such as the knee moving towards the midline (genu varus) or bending away (genu valgus). They may also notice weakness or wasting of the thigh muscle (quadriceps) or feel a foreign body within the knee joint.

- Palpation: By feeling the joint, the healthcare professional could identify swelling or bone tenderness along the outer ridge of the thigh bone. The patient’s range of motion could be limited due to discomfort, swelling, or the presence of a loose body.

One specific test used during the examination is the Wilson sign, aimed at identifying lesions on the outer aspect of the inner femoral condyle. A positive test suggests impingement of the lesion by the inner part of the tibia. However, absence of Wilson sign does not completely rule out the disease as it is not present in around 75% of patients with osteochondritis dissecans. Therefore, healthcare professionals should also monitor the patient’s walking pattern, as it may show signs such as pain-avoiding limp or outward rotation of the foot to ease weight-bearing discomfort.

Testing for Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee

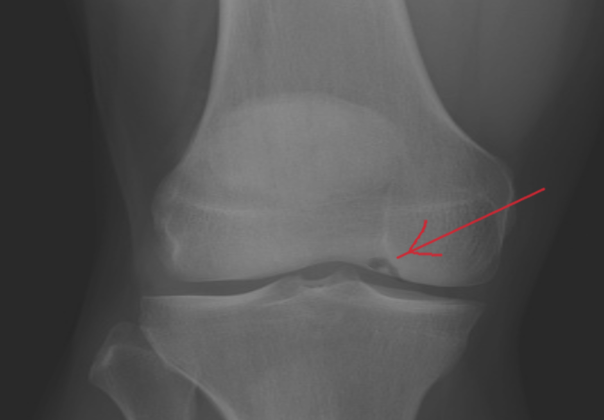

If your doctor suspects you have osteochondritis dissecans, a condition affecting the joints, a series of X-rays may be taken to pinpoint the exact location of the issue, evaluate growth plates, and rule out other potential issues. The need for these images is so that the doctors can have a clear view of the knee from multiple angles.

In the early stages, the X-rays may appear normal. However, as the condition progresses, the X-rays may show a bright clear area with different density levels. This could also show a clear line separating the affected delicate tissues from the rest of the bone.

There’s a popular classification you should know about. Cahill and Berg suggest that the knee has 15 zones where the affected conditions can be located. If lesions, which are the areas affected by injury or disease, are found in less common areas like the middle of the knee cap, the condition may not respond very well to non-invasive treatments.

Your doctor may also use Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to assess your condition. MRI scans can show if a lesion is stable or unstable, which could result in symptoms like knee swelling. You might also have an increased level of T2 signal at the connection of the host bone and the lesion, destruction of the overlying articular cartilage, multiple cyst-like foci, or a single focus of over 5 mm; any of these may indicate an unstable osteochondritis dissecans lesion. The doctor uses these MRI results to evaluate the severity of your case.

MRIs are not just crucial in determining the stability of the lesion but also vital in diagnosing osteochondritis dissecans as well as differentiating normal ossification centers of the distal femur from osteochondritis dissecans in children. However, occasionally, a type of contrast dye, “gadolinium,” might be used in your MRI scan, especially when there are questions regarding the stability of the lesion. Gadolinium aids in examining the adequacy of the blood supply to the bone fragment.

Neither should it be surprising if your doctor prescribes an arthroscopy, a non-invasive procedure using a small camera to examine the inside of your knee. This procedure is vital in assessing the stability of the lesion and deciding the most appropriate treatment plan for you.

Treatment Options for Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee

When treating osteochondritis dissecans of the knee, which is a joint condition where bone underneath the cartilage of a joint dies due to lack of blood flow, two main ways are used – non-surgical methods or surgery. The method chosen usually depends on how old the patient is, the severity of the condition, and where the disease lies in the knee.

Non-surgical treatment is usually considered for all young people who don’t have a displaced fragment, or whose disease is in the early to middle stages. The patient would have to stop participating in sports activities, rest their knee by using a brace, cast, or splint for a period ranging from 4 to 6 weeks. After this period and when the knee shows signs of healing, the patient can start physical therapy, and continue it until the knee is pain-free, has regained its full movement range, and strength. Wearing the brace is advised through the recovery period until the patient can start slowly bringing sports activities back into their routine. If done correctly, the whole process typically takes about 6 months. The patient can also use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to manage pain and swelling.

Studies suggest that this approach can successfully treat osteochondritis dissecans for about half to three-quarters of the affected patients without fragmentation. This treatment can also be chosen for adults with early stages of the disease, but the chances of it being successful is 50% or less. For patients who show no symptoms of the disease, treatment might not be necessary. But the healthcare professionals would keep a regular check until the condition shows signs of improvement during health check-ups.

If the non-surgical approach does not show any improvement after 3 to 6 months, or is considered unsuitable, surgery is suggested. For adults, surgery is the primary treatment for any symptoms related to osteochondritis dissecans, or when there’s an increase in the disease-severity in radiographs. Young people would need surgery if they have reached a severe stage of the disease with loose bodies, or have unstable lesions.

One surgical procedure called subchondral drilling is suggested if the disease’s consequences appear stable during arthroscopy. A thin wire (k-wire) is placed, leading to the growth of fibrocartilage tissue. It is suitable for young people who are still growing.

Another surgical approach is the fixation of unstable lesions, which involves repairing the disease’s consequences by fixation if they appear unstable during arthroscopy, or if they’re larger than 2 cm on the MRI scan.

Chondral resurfacing is another surgical method considered for consequences larger than 4 cm², which involves different techniques. One of them is microfracture surgery which helps increase fibrocartilage and although it yields good short-term results, it is less durable and has higher failure rates. The patients have to avoid putting pressure on the affected limb and continue doing exercises that involve moving the knee joint within a comfortable range for about 4 to 6 weeks after the surgery.

Osteochondral allografts are another approach but they’re a bit pricey. It can be done using arthrotomy or arthroscopic procedures. Arthrotomy is preferred for consequences larger than 3 cm. Autologous graft procedures help in faster recovery. Periosteal patches are implants that help with cartilage regeneration. For patients aged over 60 years, arthroplasty, a surgical procedure to restore the function of the joint, is usually recommended.

What else can Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee be?

When a young person is diagnosed with juvenile osteochondritis dissecans, it’s because other similar conditions have been considered and ruled out. These could include:

- Patellofemoral syndrome

- Patellar tendonitis

- Osgood-Schlatter disease

- Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome

- Fat pad impingement

- Symptomatic discoid meniscus

- Symptomatic synovial plica

For an adult with typical knee pain that gets worse when they put weight on it, doctors might think about the following conditions:

- Patellofemoral pain

- Knee osteoarthritis

- Chondromalacia

- Patellar tendonitis

- Meniscal tear

- Fat pad impingement

- Symptomatic synovial plica

For adults experiencing severe symptoms like unexplained swelling and mechanical symptoms without an injury, doctors would consider these conditions:

- Meniscal tear

- Osteochondral loose body

- Neoplasm (a new and abnormal growth of tissue)

What to expect with Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee

The chances of fully recovering from osteochondritis dissecans (a joint condition where bone underneath the cartilage of a joint dies due to lack of blood flow) in the knee greatly depend on the age of the patient and the specific location and appearance of the damaged area through an MRI or similar imaging test. Younger patients, especially children, are usually in a better position for a complete recovery through non-surgical treatment.

If the disease is ignored or not treated, adults are more likely to develop arthritis (the swelling and tenderness of one or more of your joints). There are also certain factors that can make the condition more severe or increase the likelihood of a poor outcome. These include:

* The damaged area is on the outer part of the knee joint or kneecap

* Advanced disease stages revealed through imaging like an MRI

* The damaged area appears hardened on the X-ray or there is joint fluid present behind the diseased area on the MRI

How well you recover also depends a lot on how well someone allows their body to heal. Individuals with less severe disease, who let their bodies heal fully, can usually recover fully and regain complete knee ability. Young patients with early stages of the disease have a 95% chance of regaining full knee function. However, if the disease is more severe and full recovery isn’t achieved, there can be ongoing mild to severe pain, mechanical symptoms, and potentially development of arthritic disease. In fact, adult patients with advanced stages of the disease have a 50% chance of developing chronic symptoms.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee

Osteochondritis dissecans can lead to several complications:

- Degenerative changes in the joint

- Bony fragment not properly healing

- Constant pain and mechanical issues

- Surgical complications, such as post-surgery infection

- Possible pneumonia, excessive bleeding, and reactions to anesthesia

- Clots in veins due to lack of movement

Preventing Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee

Osteochondritis dissecans is a condition where parts of the bone and cartilage under the surface of the knee joint separate from the larger bone. Sometimes, these fragments are stable, and sometimes, they move around. It’s currently impossible to prevent this condition and it’s important for the patient, their family and trainers to understand that long-standing knee pain in a young athlete isn’t normal. It’s not just “growing pains” or something that should be ignored.

Young patients, their families and coaches should also understand that with the right treatment, there is a 95% chance of the patient’s knee returning to normal. This treatment process often includes keeping the knee still, physical therapy, regular imaging tests to monitor progress, and staying away from certain activities until the knee is completely healed. Sometimes, young patients may have fragments that move around or don’t get better with non-surgical treatments, and in these cases, surgery may be required.

Adults with this condition should know that even though non-surgical treatments may be used, there’s a high chance they might need surgery. In both children and adults, osteochondritis dissecans could lead to lifelong pain and issues with the knee’s function if not treated properly.