What is Patellar Tendon Rupture?

A patellar tendon rupture is when the tendon connecting the kneecap to the shinbone completely tears. This type of injury is most commonly seen in men in their 30s or 40s, and it usually happens when a weak tendon is put under intense strain. These tears can be categorized as either acute, meaning they happened recently, or chronic, meaning they’ve been present for a while.

Whenever this injury happens, it’s important to get medical attention and likely undergo surgery quickly. This is because the patellar tendon is an essential part of the knee’s functionality, specifically when it comes to extending and straightening the knee. If your knee can’t properly extend and straighten, it can severely limit your ability to walk or move around.

When it comes to treating the injury with surgery, the timing and location of the tear really matters. If the tear happened very recently, it can usually be repaired. However, if the tear has been around for a while, it often needs a tendon reconstruction.

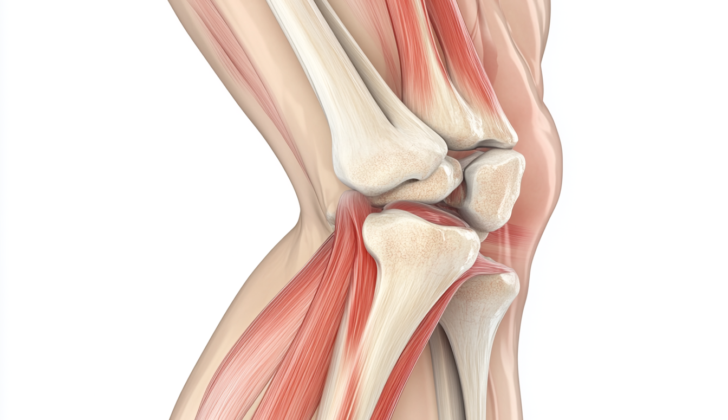

Now, let’s talk a bit about the anatomy of your knee. The knee extension mechanism (which helps your knee to extend or straighten) includes parts like the quadriceps muscle, quadriceps tendon, kneecap, patellar tendon, and the shinbone.

The quadriceps muscle, in particular, consists of four separate muscles that all connect to the kneecap. Also around the kneecap, you’ll find the medial and lateral patellar retinaculum that provide some knee extension and help in raising your straight leg, even if your kneecap or quadriceps tendon are damaged.

The kneecap itself is a very special type of bone that helps to increase the power and efficiency of knee extension. It also gets deeply involved in an action when you bend your knee, helping to bear the force exerted when you climb stairs or bend deeply.

Finally, the patellar tendon is the connective tissue that joins your kneecap to the shinbone. It’s about as wide as a large paper clip and about as long as a small credit card, with a thickness slightly less than that of a pencil. This crucial tendon connects the quadriceps muscles to the lower leg, allowing for effective movement.

What Causes Patellar Tendon Rupture?

Tendon rupture happens when a tendon, the strong flexible tissue connecting muscle to bone, gets too weak and breaks. This can occur due to tendinosis, a condition where the tendon slowly wears out over time. Also, inflammation, such as patellar tendonitis, which is irritation of the tendon in the knee, can cause the tendon to weaken, making it more likely to rupture.

There are some health conditions that can cause a tendon to become weak, these conditions also make a person more likely to have a tendon rupture. Some of these conditions, also known as risk factors, are:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus: This is a disease where your immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissues in your body.

- Rheumatoid arthritis: This is a condition causing inflammation in your joints.

- Chronic renal disease: Long-lasting disease affecting your kidney’s ability to function properly.

- Diabetes mellitus: A chronic condition where your body has difficulty regulating its sugar levels.

- Renal dialysis: A treatment that helps filter and purify the blood using a machine, usually required when the kidneys are not working properly.

- Chronic corticosteroid use: Long-term use of a group of drugs used to reduce inflammation.

- Fluoroquinolone antibiotics: A type of medication used to treat bacterial infections.

- Corticosteroid injections: Shots that reduce inflammation and pain.

- Patellar tendinopathy: Damage or injury to the tendon in the knee.

- Previous injury: Sustaining an earlier injury can increase the risk of future ruptures.

- Overuse injury: An injury caused by repetitive motion or stress on a body part.

- Patellar degeneration: Deterioration or wear and tear of the kneecap.

Besides these conditions, certain activities, like sports that put a lot of stress on the tendons, could also increase the risk of a tendon rupture. It’s crucial to promptly treat and manage these conditions, and any strenuous activities should be done within a person’s ability to avoid overuse or injury.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Patellar Tendon Rupture

The knee extensor mechanism, which helps us extend or straighten our knees, can get damaged in several areas. The most common spots where this happens are in the patella (knee cap), the quadriceps tendon (the tendon connecting the large thigh muscle to the knee), and the patellar tendon (the tendon joining the kneecap to the shin bone).

Of these, patella fractures or breaks in the kneecap are much more common. They occur over double the rate of tendon ruptures (where the tendon gets torn). Among the tendon ruptures, the quadriceps tendon is more likely to get injured, and this is especially true for people over 40.

- In the U.S., each year 1.3% people suffer from quadriceps tendon ruptures and less than 0.5% suffer from patellar tendon ruptures.

- Males experience these knee injuries more than females. This is because men are physically stronger, which makes them more likely to rupture the knee’s extensor mechanism.

- On the other hand, women tend to have more flexible ligaments and hormonal changes due to their menstrual cycle may provide some protection against these injuries.

Signs and Symptoms of Patellar Tendon Rupture

Patients suffering from an acute patellar tendon tear typically experience knee pain below the kneecap, swelling, difficulty bearing weight and straightening the leg. They might also describe hearing an audible “pop” or feeling their knee give way during any sudden quadriceps muscle contraction when the knee is bent, like during jumping sports or missing a step on the stairs. Many patients may already have pre-existing pain around the kneecap or the patellar tendon, which could suggest an underlying condition known as tendinosis. A full history may reveal a risk factor or predisposition to a tendon rupture.

It’s important to note that the distinction between an acute and chronic tendon rupture sparks ongoing debate in the medical community. However, typically, chronic ruptures refer to those appearing six weeks post-injury.

The physical examination of the knee should begin with a visual inspection. Among other things, the healthcare provider should examine the skin around the knee for signs of direct injury, any associated swelling or filled knee joint, and compare the kneecap height of both the affected and unaffected sides. A patellar tendon rupture usually results in the affected kneecap sitting higher than the unaffected one.

Further, physical touch is used to examine the bony and soft tissue structures of the knee. This touch exam usually covers three main areas of the knee: the medial (inside) aspect, the midline, and the lateral (outside) aspect.

- Medial aspect targets:

- Vastus medialis obliquis

- Superomedial pole patella

- The medial facet of the patella

- Origin of the medial collateral ligament (MCL)

- Midsubstance of the MCL

- Broad insertion of the MCL

- Medial joint line

- Medial meniscus

- Pes anserine tendons and bursa

- Midline knee targets:

- Quadricep tendon

- Suprapatellar pouch

- Superior pole patella

- Patellar mobility

- Prepatellar bursa

- Patellar tendon

- Tibial tubercle

- Lateral aspect targets:

- Iliotibial band

- Lateral facet patella

- Lateral collateral ligament (LCL)

- Lateral joint line

- Lateral meniscus

- Gerdy’s tubercle

A patient with a ruptured patellar tendon will have a gap that can be felt below the bottom edge of the kneecap, and they will also have tenderness about the infrapatellar aspect of the knee. The healthcare provider will also test the patient’s knee motion range and muscle strength, as these aspects are critical in the potential diagnosis of a patellar tendon rupture. A patient suffering from an acute rupture will have limited knee motion due to pain and damage, can’t extend their knee, and may struggle with straight leg raise exercises. If the patellar tendon is the only portion of the extensor mechanism ruptured, active extension of the knee may still be possible, but the knee will lag behind by a few degrees.

It is vital to diagnose a patellar tendon rupture or any disruption of the extensor mechanism promptly, as any delay could affect the treatment outcome. If needed, removal of fluid accumulation in the knee followed by local anesthesia may help in diagnosing the issue. If patients can perform a straight leg raise with local anesthesia, they are more likely to have pain due to a different issue rather than a patellar tendon rupture.

Testing for Patellar Tendon Rupture

When your doctor suspects you have a knee injury, they’ll likely start by taking X-ray images of your knee from the front and side. If your patellar tendon (the tissue that connects your kneecap to your shin bone) is completely torn, your kneecap may appear higher up than normal. This is known as patella alta.

To confirm this, your doctor may use a measurement method called the Insall-Salvati ratio. This is done by comparing the length of your patellar tendon to the length of your kneecap. Ideally, this measurement is taken from a side-view X-ray when your knee is bent to 30 degrees. Normal results are between 0.8 and 1.2. If this ratio is more than 1.2, you have patella alta. If it’s less than 0.8, it means your patella is lower than usual, situation known as patella baja.

Your doctor might also look for signs of bone fractures or other knee injuries in these X-ray images. If they suspect a patellar tendon rupture, they might order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. This type of test provides detailed images and can accurately identify if the tendon is partially or completely torn. It can also show the exact location of the tear, check for other signs of tissue damage, and determine the position of your kneecap.

Ultrasound imaging can also be helpful, especially when trying to detect and locate a tendon tear. It’s usually a less expensive option than MRI, and may be more convenient, depending on the availability of the equipment and someone who is experienced in performing the test.

Treatment Options for Patellar Tendon Rupture

When the patellar tendon, which connects your kneecap (patella) to your shinbone, is entirely torn, surgery is usually necessary. This is due to the significant impairment that occurs in the ability to move the knee. Although it’s not an immediate emergency, it’s recommended to have the surgery done quickly. This can help to prevent further complications that may require a more complex reconstruction of the tendon.

However, surgery may not be necessary for partial tears of the patellar tendon where the knee’s motion is still functional. Non-surgical options could also be considered for patients who are not suitable for surgery due to existing health conditions. This non-surgical treatment involves keeping the knee straight and gradually restoring movement through weight-bearing exercises.

Surgical treatment can take two forms: a primary repair or a tendon reconstruction. Primary repair, which is usually recommended for complete patellar tendon tears, involves sewing the two ends of the ruptured tendon together. The type of repair used depends on the location of the tear. If the tear is in the middle of the tendon, an end-to-end repair is usually performed. If the tear has occurred near the top of the tendon, a transosseous tendon repair is done, in which holes are drilled through the kneecap to anchor the tendon. If the tear is at the bottom of the tendon, a suture anchor tendon repair is done.

On the other hand, if the patellar tendon is severely damaged or degenerated, or when a primary repair is not possible, a tendon reconstruction may be necessary. In these cases, a new tendon is created from tissues in your own body (autograft) or from donor tissue (allograft). It’s important to treat patellar tendon ruptures promptly because delay can lead to the tendon becoming less flexible and more prone to adhesions or degeneration, making repair more complicated.

The different types of tissues potentially used in a tendon reconstruction include:

- Semitendinosus (one of the hamstring tendons at the back of the thigh)

- Gracilis (a tendon from the inner thigh)

- Central part of the quadriceps tendon-patellar bone (could be from the same knee or the other knee)

- Achilles tendon with a small piece of bone attached to it

The specific type of repair or reconstruction and the choice of tissue for reconstruction will depend on multiple factors, including the specifics of the tear, the patient’s overall health, and the surgeon’s expertise.

What else can Patellar Tendon Rupture be?

Doctors may need to check for the following conditions, which could be similar to the one you have, and need similar treatment:

- Quadriceps tendon rupture – a tear in the large tendon just above your kneecap.

- Patella fracture – a break in your kneecap.

- Tibial tubercle avulsion fracture – a crack where a tendon attaches to your shinbone just below the knee.

What to expect with Patellar Tendon Rupture

In general, patients who quickly receive surgical treatment for ruptured patellar tendons often report good to excellent results. However, if the diagnosis is missed or delayed, if treatment is not prompt, or if there are mistakes during the surgery, outcomes are often poor, with complications and failures more likely.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Patellar Tendon Rupture

Here are some potential issues you might experience after a medical procedure:

- a second rupture,

- lingering weakness in your extensor muscles,

- an ongoing issue with fully straightening your knee,

- general stiffness in your knee,

- atrophy, or weakening and loss of muscle mass, in your quadriceps,

- infection.

Recovery from Patellar Tendon Rupture

After surgery, the way you regain your strength and mobility, also known as your post-op rehab, can vary depending on your surgeon’s recommendations. However, below are some general guidelines you may follow:

First two weeks post-surgery:

– Your main aim is to protect the surgical repair of the tendon.

– You can put weight on your leg as much as it feels comfortable, using crutches and a knee brace that keeps your leg fully extended.

– The surgeon who performed your surgery will decide how much you can move your knee based on how well the surgery went.

Two to six weeks post-surgery:

– Your aim remains the same: to protect the surgical repair of the tendon, and also to walk as normally as possible with crutches and your knee brace.

– You keep putting weight on your leg as comfortably as possible with crutches and your knee brace.

– You start to gently move your knee from 0 to 90 degrees of flexion, but don’t actively extend your quad muscles.

– The surgeon will again assess how much you can move your knee based on how well the surgery went.

Sixth to 12th week post-surgery:

– Now your aim is to walk normally on flat surfaces, to reduce the use of crutches, and to start active quadriceps contraction. Your knee brace may be opened to allow your knee to bend.

– You can slowly start putting more weight on your knee as it bends, but avoid doing that once your knee bends more than 70 degrees.

– Start doing active knee movement, progressive light squat, leg press, core strengthening, and other therapeutic exercises.

12th to 16th week post-surgery:

– The goal now is to walk normally on all surfaces without a brace, fully move your knee, adequately stand on one leg, and comfortably squat to 70 degrees of flexion.

– You can start drills that involve no-impact balance and proprioception (this is the sense of the relative position of your own parts of the body and strength of effort being employed in movement)

– Keep up with your therapeutic exercises, quad and core strengthening

16th week post-surgery and beyond:

– Your goal is to have good control over your quad muscles, and not to have any pain while doing sports or work-related movements, including impact activities.

Return to Sport Criteria:

– You should be able to control your movements in various planes without pain or swelling.

Preventing Patellar Tendon Rupture

It’s critical for patients to understand the surgery they’re about to undergo, and even more importantly, the need to diligently follow the recovery process outlined by the doctor, especially the physical therapy sessions. This holds true even for those patients who will not be having surgery but will be encouraged to start therapy sessions. Not diligently following through with therapy sessions, both those scheduled with a professional and those recommended for at home, can lead to permanent loss of function in the affected part.

Patients should also keep their expectations realistic based on their age, how physically fit they were before the injury, and what their daily life and work look like. If the patient can successfully undergo surgery and remain committed to properly following the recovery and care plan outlined by their doctor, they can hope for a favorable outcome.