What is Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis?

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is a kind of tumor that mostly affects soft tissues lining the joints and tendons. These tumors are most commonly seen in the knee, hip, and ankle joints. PVNS often starts subtly, with symptoms sometimes persisting for years before the condition is diagnosed. Furthermore, this type of tumor is typically more aggressive compared to another major subtype called giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath (GCT-TS).

According to data from 1980, approximately 9.2 new people per million get diagnosed with PVNS each year in the United States. Even with treatment, there’s a chance that PVNS might come back, these chances range from 14 to 55%.

What Causes Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis?

Pigmented villonodular synovitis, or PVNS, is a condition that’s been found to contain abnormal growth parts. Most people with PVNS have a change in the structure of chromosome 1p13. This leads to too much of a substance called colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1).

When too much CSF-1 is produced, groups or clusters of abnormal cells form. These clusters then create areas of excessive growth in the soft tissue lining the joints. This soft tissue is known as synovial cells.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

Pigmented villonodular synovitis is a condition that often takes a long time to diagnose, with an average time of 18 months from when symptoms first appear. There isn’t clear agreement on whether it affects men and women equally or if women are slightly more likely to be diagnosed, especially when the disease is localized to one area. However, it’s been established that this condition is less common in children, making it more likely for it to be misdiagnosed in this age group.

- The average time from onset of symptoms to definitive diagnosis is 18 months.

- Studies vary on whether men and women are affected equally, or if women are slightly more likely to get the disease when it’s localized.

- The condition is less common in children, leading to more frequent misdiagnoses in this group.

Signs and Symptoms of Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

Pigmented villonodular synovitis is a condition that involves a slow-growing tumor, usually occurring on a joint. Initially, a person with this condition might notice an unexplained, painless swelling in the affected joint. But as the tumor grows larger, they may experience pain, swelling, and limited range of motion in the affected area.

As the disease progresses, individuals may experience repeated episodes of bleeding within the joint (hemarthrosis) which leads to increasing joint stiffness and potentially severe joint damage. Typically, this condition affects one joint at a time, but in rare cases, it may affect multiple joints (polyarthropically). Keep in mind that symptoms might appear gradually over time. As a result, people often undergo numerous tests to rule out other potential causes of joint pain.

Synovitis typically occurs in the large joints of the arms and legs, but it primarily affects the knee, specifically a region called the infrapatellar fat pad in the patellofemoral compartment. This is the area situated below the kneecap (patella).

Testing for Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

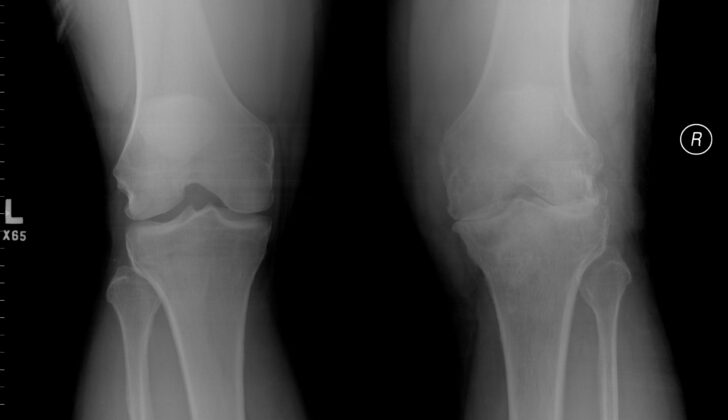

Doctors usually diagnose pigmented villonodular synovitis, a joint condition, using a combination of different imaging techniques. Firstly, they perform an X-ray which often displays signs of swelling in the soft tissues around the affected joint, and erosion of the bone.

The next step usually involves an MRI scan, as it is a more sensitive imaging examination. The MRI typically showcases a buildup of fluid in the joint, iron-rich hemosiderin deposits, enlargement of the synovium (the soft tissue that lines the spaces of diarthrodial joints), and further bone erosion.

Although you might expect an increase in routine blood markers for inflammation (like erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein) due to visible swelling, tests don’t usually show this in majority of incidents.

There is a theory that having prior injuries in the joint might lead to pigmented villonodular synovitis, but this link is not consistently proven by all researchers.

Furthermore, an incidental hematoma (a collection of blood outside of blood vessels) found while draining fluid from a chronically inflamed joint might give an important hint about the diagnosis.

Treatment Options for Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is a condition that usually demands treatment through surgery, specifically through an open procedure or a less invasive procedure called an arthroscopic approach, which uses special tools and small incisions. Both methods seem to have similar chances of the disease coming back after the surgery. However, patients treated with the arthroscopic procedure tend to have better movement and function of the joint after the operation.

Despite the effectiveness of surgical treatments, there is still up to a 50% chance that PVNS will come back after the surgery. This has led researchers to look into additional treatment options. One such alternative is external beam radiation therapy, which has been found to control the disease in up to 95.1% of cases when used on its own. It has also been shown to significantly reduce the chances of PVNS returning after surgical treatment.

Recently, scientists have uncovered more about the CSF-1 pathway that is involved in PVNS. This discovery has led to further research into systemic therapies, including the use of monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Monoclonal antibodies are proteins made in a lab that can bind to specific targets on cells. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are drugs that block the enzyme tyrosine kinase, which is involved in cell growth and division.

Two agents, called emactuzumab and PLX3397, are showing potential in treating PVNS. Emactuzumab works by directly attaching itself to the CSF-1 receptor on the surface of macrophages (a type of white blood cell involved in our body’s immune response), which helps limit or eliminate the effects of an increased production of CSF-1. In a recent clinical trial, 26 out of 28 patients with PVNS had a positive response to treatment with this drug. On the other hand, PLX3397 operates by obstructing molecular endpoints of CSF-1 and has shown a positive effect in 52% of patients with a well-tolerated side effect profile.

The latest advancement in systemic therapy for PVNS is pexidartinib, a drug that works against the CSF-1 receptor. Given the green light by the FDA in August 2019, pexidartinib is used for patients with a widespread form of the disease who most likely won’t benefit from surgery.

What else can Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis be?

Pigmented villonodular synovitis, a joint condition, can be challenging to diagnose. This is because it shows symptoms similar to several other health issues, including:

- Rheumatoid arthritis – a long-term, chronic disease causing inflammation in the joints.

- Septic joints – A painful infection in a joint.

- Hemarthrosis – also called ‘blood within a joint’.

- Various types of neoplasia or uncontrolled, abnormal growths.

This means, pigmented villonodular synovitis can be misdiagnosed, even with advanced imaging and diagnostic tests. For instance, it can be wrongly identified as a ganglion (a fluid-filled bump below the skin), schwannoma (a benign nerve tumor), or hemangioma (a cluster of extra blood vessels).

What to expect with Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) doesn’t often lead to fatal outcomes, but it’s important to note that it can significantly affect a person’s quality of life. PVNS is a condition that can make everyday tasks challenging to perform, leading to a reduced quality of life.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

If pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is not treated, it can lead to several complications. These can include serious changes to the joint, such as becoming deformed or developing degenerative changes and osteoarthritis. If arthritis gets very severe, it can erode the surfaces of the joint, cause destruction of the outer bone and might eventually make it necessary to fuse the joint or even amputate the limb.

Other complications associated with PVNS treatment. For example, pexidartinib, a medicine used to treat the condition, can potentially harm the liver. That’s why patients on this medication will be closely monitored, especially the liver enzymes.

The type of surgery a patient might get, either arthroscopic (using a small camera and instruments) or open surgery, can lead to different complications. Open surgeries usually mean a longer stay in the hospital and a longer recovery period. In contrast, arthroscopic surgeries need a surgeon with specific technical skills and may not work well for removing large masses that have spread to nearby tissues.

It’s very rare, but PVNS can spread, or metastasize, to other parts of the body. This can be either benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). There have been reports of PVNS spreading to the lungs, muscles, and lymph nodes.

- Possible joint deformity

- Development of osteoarthritis

- Need for joint fusion or amputation if arthritis becomes severe

- Liver damage due to treatment with pexidartinib

- Extended hospital stay and longer recovery after open surgery

- Surgeons require technical expertise to perform arthroscopic surgery, which may not work for all patients

- Rare instances of PVNS spreading to lungs, muscles, or lymph nodes

joint effusion due to pgimented villonodular synovitis (PVNS).

Preventing Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

Doctors must tell their patients about both surgery and medicine-based treatment options for a condition called pigmented villonodular synovitis. This way, patients can make the best decision about their health. If a patient decides to have surgery, the doctor should talk about the benefits and drawbacks of two types of knee surgeries: open surgery and arthroscopic (minimally invasive) surgery. The doctor and patient will consider factors like the size and position of the tumor and the patient’s desired level of physical function after the surgery.

It’s also really important for the patient to know about the surgery’s risks alongside its benefits. There’s another key point to keep in mind: this condition tends to come back again even after surgery, so the patient needs to be aware of this.

Pigmented villonodular synovitis can look similar to many other diseases and is often wrongly diagnosed. This is why patients might need to see doctors from different specialties to make sure they get the right diagnosis and treatment plan.