What is Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee?

Osteonecrosis (ON), also known as bone death, is a degenerative disorder that occurs when the cells within a bone die due to the blood supply being interrupted. The condition was first identified in 1968 and applies to three different conditions associated with the knee: primary or spontaneous osteonecrosis, secondary osteonecrosis, and post-surgical osteonecrosis that happens after knee surgery.

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SPONK) is the most discussed in medical studies and literature. However, it is the least understood, and the causes behind it remain unclear. Due to its gradual onset and often vague symptoms, SPONK can be hard to diagnose quickly, which makes prompt treatment challenging. If any of these three types of ON is untreated and becomes advanced, the articular surface of the joint can eventually collapse, resulting in end-stage arthritis that often requires surgery. In this article, we’re focusing on secondary osteonecrosis of the knee (SON), exploring its causes, how to diagnose it, and how it’s treated.

What Causes Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee?

SON, or Sickle cell-associated osteonecrosis, is a condition that has numerous well-known triggers which can be split into direct causes like sickle cell disease, certain blood disorders, and Gaucher’s disease, a rare genetic disorder. There are also indirect triggers such as alcohol consumption, obesity, and use of a type of medication called corticosteroids. Alcohol abuse and steroid usage are observed in over 90% of SON cases.

Research has shown that drinking too much alcohol and using corticosteroids can cause fat cells in the bone marrow to enlarge. This increased size of the cells leads to higher pressure within the bone, which can disrupt the blood supply, leading to bone death or “ischemia”.

This idea has been broadened to include other risk factors like Gaucher’s disease (a type of disorder where a specific type of fat accumulates in cells and certain organs), certain conditions related to pressure changes, and some specific blood disorders. There are also triggers like smoking and sickle cell disease, which are thought to cause SON by blocking blood flow, otherwise known as “vaso-occlusive effects”. In sickle cell disease, the red blood cells are abnormal in shape, making them more likely to stick together and to the walls of blood vessels, blocking the blood flow. This can cause a lack of blood flow to the bone, similar to what can happen in other blood vessels in the body. However, so far, there has been no genetic factor found to be significant in causing SON according to existing literature.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee

The knee is often affected by a condition called osteonecrosis; it’s actually the second most common joint to develop it after the head of the femur, the bone in the upper part of your leg. Osteonecrosis can also appear in other body parts like the shoulder, ankle, jaw, and spine.

In the knee, the most widespread type of osteonecrosis is known as SPONK. It’s usually diagnosed in people who are in their 60s and is found to be more common in females. SPONK typically affects only one side of the knee, causing sudden localized pain. It doesn’t seem to be associated with any known risk factors and usually doesn’t show up in other joints at the same time. If the affected area is small, the condition usually improves with conservative treatments and tends to resolve on its own. However, if the area is larger, the condition can worsen and cause the tissue under the cartilage of the joint to collapse.

Secondary osteonecrosis (SON) is another variant seen in the knee and is usually diagnosed in patients under the age of 40. This form of osteonecrosis frequently results in multiple affected areas in several joints at the same time. When it comes to knees, SON often affects both sides and can involve different parts of the femur and tibial plateau, which are parts of the knee joint. It affects both knees in 80% of cases, and the femoral head is also affected in 90% of cases.

The prevalence of secondary osteonecrosis (SON) is hard to determine, as it may often go underreported. This is because patients may be diagnosed with advanced osteoarthritis, when in fact, they may have first had undiagnosed osteonecrosis.

Signs and Symptoms of Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee

People suffering from SON (Spontaneous Osteonecrosis) of the knee usually show gradual and mild symptoms focused on the inner (medial) or outer (lateral) part of the knee end, or both. You’ll typically observe this condition in people younger than 45. The symptoms usually appear in both knees, and these individuals often also have osteonecrosis, a similar condition, in other large joints.

During a physical examination, patients commonly experience pain, both when they’re resting and during weight-bearing exercises. The most typical symptom doctors observe is localized pain when the affected area is touched. Patients with mild SON can still move their knee in a full range normally, though pain might limit this.

Testing for Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee

It’s important for doctors to identify people at high risk of knee osteonecrosis (SON), a disease that causes decreased blood flow to bones in the knee, leading to their death and potentially causing joint issues. People with certain symptoms and associated risk factors must be given immediate attention.

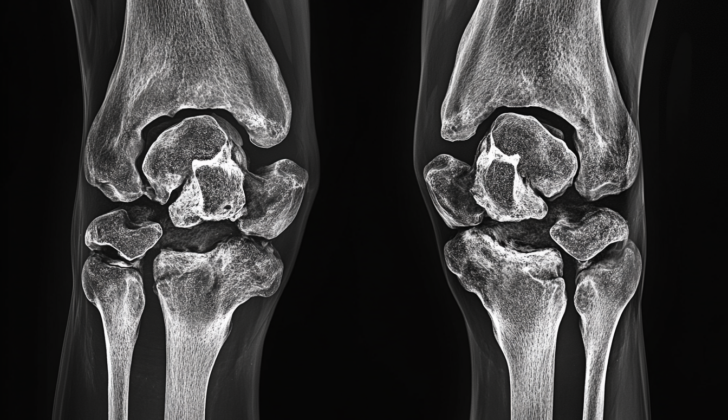

Diagnosing this condition usually involves getting front and side x-rays of both knees. In some cases, doctors use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – a technique that uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed pictures of your body’s organs and tissues. This detection method is important as an earlier diagnosis can lead to better treatment outcomes for patients.

In the past, another imaging procedure called radionucleotide scanning was used to examine and measure the extent of ON. However, research suggests that MRI is more effective. One study found that while bone scanning could detect only 64% of knee ON cases, MRI detected all.

Currently, there aren’t any definitive MRI findings that could indicate early stages of SON. Nevertheless, doctors might suspect this condition if they see certain bone swelling patterns on the MRI scan. This is because SON can affect various parts of the knee bone, unlike other types of osteonecrosis that only impact certain areas.

Often, with SON, doctors can observe a ‘rim’ or ‘double halo’ sign next to the area of bone death on an MRI image. One study found this sign in 70% of SON cases but not in other types of osteonecrosis. More research is needed to understand whether this sign can indeed indicate early stages of SON.

To assess the severity of SON and guide treatment options, doctors use systems to classify the condition. One is the Koshino staging system, initially created for another type of osteonecrosis. Another is the modified Ficat and Arlet system, initially developed for osteonecrosis of the hip but adapted for the knee.

The latter system is more commonly used and classifies osteonecrosis into four stages:

- Stage I – The affected area looks normal on images.

- Stage II – Images show abnormalities or hardening in the bone, but no fractures or flatness in the joint surface.

- Stage III – Images show a ‘crescent sign’ or evidence of fracture within the subchondral bone (the layer of bone right under the cartilage).

- Stage IV – Images show narrowing of the space within the joint along with the presence of cysts and bone spurs (abnormal bone growths).

Treatment Options for Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee

Spontaneous Osteonecrosis of the Knee (SON) treatment depends on the severity of the condition and specific patient factors. SON mainly affects younger individuals, and where possible, treatment aims to preserve the knee joint. However, non-surgical treatments often prove unsuccessful, with a study finding that 80% of patients relying on non-weight bearing treatment needed knee replacement surgery within 6 years.

Non-surgical treatments, like using non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (medications to reduce pain and inflammation), painkillers, and limiting weight-bearing activity, are typically only recommended for those with early and symptom-less stages of SON.

Recent research has found potential benefits in managing SON through the use of drugs called bisphosphonates and prostaglandin I-2, particularly in earlier stages of the disease. Those with more advanced osteonecrosis didn’t see as much improvement. Further large-scale research is needed to better understand these treatments’ effectiveness.

There are several techniques for preserving the knee joint that have been studied and shown some promise. These techniques mainly aim to delay the need for knee replacement surgery in young, active patients. If the cartilage surface (the protective tissue that allows joints to move smoothly) is intact and free from arthritis, techniques such as core decompression and bone grafting (taking bone from one area and transplanting it to another) can be useful.

An alternative form of core decompression surgery called percutaneous drilling was reported to have a 92% success rate over a three-year period, making it an effective procedure to relieve symptoms and postpone the need for knee replacement surgery.

If the bone beneath the cartilage collapses or the disease has progressed to more severe stages, total knee replacement is the only option. Knee replacement surgery aims to restore normal joint anatomy to improve symptoms and functionality. A review found that 97% of patients who underwent this procedure with cemented components achieved a good outcome, according to a knee score scale. In cases with severe bone disease or reduced bone strength, additional supports may be used to ensure the prosthesis’s stability and fixation.

What else can Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee be?

Diagnosing a condition called SON, or secondary osteonecrosis, can be difficult. This is often because healthcare professionals are not very familiar with this disease. Knee pain, a common symptom of SON, is frequently mistaken as pain coming from a hip problem that a patient might already have. When doctors carry out investigations on these patients, they generally focus on abnormalities within the joint first. Since patients with SON usually have hip problems too, pain in the knee should prompt further exams rather than attributing it to an existing condition. Secondary osteonecrosis is often mixed up with several other conditions, including:

- Postraumatic osteonecrosis

- Osteochondritis dissecans

- SPONK

- Infections

- Fractures

- Injuries to the meniscus (a piece of cartilage in the knee)

The differences between these types of osteonecrosis are quite distinct, and don’t often overlap with each other. That being said, there’s no excuse for confusing these different conditions, as pointed out in this article.

What to expect with Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee

There isn’t much research available that details how this disease naturally progresses over time. Most studies focus on how to treat the disease after it has advanced considerably. If not diagnosed early, people with this condition, known as SON, will eventually develop severe osteoarthritis, a type of joint disease that causes tissue breakdown and pain. When this happens, they will need a total knee replacement.

Several studies have shown really positive outcomes for patients with SON who undergo a total knee replacement. This is largely due to modern advancements in surgery, better-designed knee implants, and improved medical care before, during, and after surgery. These advances have significantly improved the results for patients who undergo a total knee replacement due to SON.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee

Osteonecrosis involves the death of bone cells and tissues, and this damage can occur for a variety of reasons. Essentially, when there’s inadequate blood flow to a certain part of the bone, it triggers tissue death causing the bone to break down. As this process takes over, it leads to the formation of a non-cellular region that weakens the bone’s ability to maintain its structure, potentially causing the affected joints to collapse.

The disease is degenerative, meaning it progressively worsens. Without diagnosis and treatment, the patient’s health inevitably declines. If caught early, conservative treatment might prevent the need for surgery, a prospect that comes with its own set of risks. Unfortunately, it’s not very common to catch this disease in its early stages. Even when it is discovered early, there’s no guarantee the patient won’t require surgery down the line.

Common Symptoms of Osteonecrosis:

- Damage to bone cells and tissues

- Inadequate blood flow to the bone

- Bone tissue death

- Formation of non-cellular region

- Structural weakening and potential collapse of the affected joints

Potential Consequences of Untreated Osteonecrosis:

- Progressive deterioration of patient’s health

- Possibility of needing surgery, even if caught early

Preventing Secondary Osteonecrosis of the Knee

When a patient is first diagnosed with a disease, it’s crucial that they are educated about how the disease can progress and what treatment options are available to them. Understanding more about a specific disease such as osteonecrosis can help primary doctors to quickly and effectively refer their patients to orthopedic surgeons when required. It’s important that orthopedic surgeons actively share the latest information with patients and other medical professionals, as this can improve patient care overall.

An orthopedic surgeon is a doctor specialized in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases related to the musculoskeletal system – the bones, joints, ligaments, muscles, nerves, and skin. As such, orthopedic surgeons should closely watch patients who have SON (short for osteonecrosis). Osteonecrosis is a disease that occurs when blood flow to an area of the bone is restricted, causing bone death. Monitoring lets the surgeon stay informed about any changes or developments in the disease.