What is Talocalcaneal Coalition?

The talocalcaneal coalition is a common reason for painful flat foot, typically in older children or teenagers. It’s an irregular link between two bones in the foot, the talus and the calcaneus. This coalition can be made of fibrous tissue (like ligaments or tendons), cartilage, or bone. Even though a person is born with this, it only starts causing discomfort once the fibrous link becomes a stiff bar of cartilage and then later, a rigid bar of bone. This usually happens between the ages of 12 and 15.

This condition causes the peroneal muscles – muscles on the outside of the calf, to spasm in a painful, rigid flat foot. In a rigid flat foot, the foot does not arch correctly and results in pain or discomfort. However, only a small fraction of those with a talocalcaneal coalition experience this symptom.

There’s a joint in the foot called the subtalar joint, that has three sections: front, middle and back, that join up with matching sections on the heel bone. Historically, the middle section was thought to be the most often affected by a talocalcaneal coalition. However, some experts now believe the back section, which is the largest, might be more commonly involved. The size of the talocalcaneal coalition can affect how successful treatment is after its removal.

The talocalcaneal coalition is the second most common irregular link between bones in the foot after the relationship between the heel and the navicular bone, which is another bone in the foot. These coalitions usually cause a slow flattening of the arch in the foot, leading to a flat foot and stiffness in the joint.

Interestingly, there is evidence of this condition in historical civilizations, like the Mayans and pre-Columbian Indian societies. The talocalcaneal coalition was first documented in medical literature in 1877, and connections to flat feet were established in the early 20th century.

What Causes Talocalcaneal Coalition?

Talocalcaneal coalitions are connections between the talus and calcaneus bones in your foot. These can be either something you’re born with (congenital) or something that develops over time (acquired).

The most common type is congenital, meaning it happens when a baby is still developing in the womb. This is believed to be due to a flaw in how certain cells (mesenchyme) form and differentiate. This malfunction is thought to follow a specific pattern of inheritance, passed down from parent to child, but doesn’t always show up in each generation (variable penetrance). These congenital coalitions often start as fibrous connections and might later turn into cartilage or bone.

A theory suggested that the coalitions are formed from extra bones that eventually solidify into nearby bones. This theory, however, was disproved after studies revealed the presence of these coalitions in developing fetuses.

The acquired type is less common and can occur because of an injury, wear and tear over time (degeneration), inflammation of the joints (inflammatory arthritis), abnormal growths (neoplasia), or infections in the back or middle of the foot (hindfoot or midfoot).

It’s also worth noting that these bone coalitions have been linked with certain conditions, such as Apert syndrome, Nievergelt-Pearlman syndrome, and clubfoot deformities.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Talocalcaneal Coalition

The tarsal coalition, a condition related to the foot, isn’t all that common. It only affects between 1% and 2% of the population. But research done on cadavers suggests it could be as high as 13%. Most of these cases, about 45%, are due to a type called talocalcaneal coalition.

- The tarsal coalition is found in about 1% to 2% of people.

- However, studies on cadavers show a prevalence of about 13%.

- About 45% of all tarsal coalitions are talocalcaneal coalitions.

- Symptoms from a talocalcaneal coalition usually show up during early teenage years, especially between ages 12 to 15, when the underlying coalition solidifies.

Signs and Symptoms of Talocalcaneal Coalition

Some individuals, often adolescents, may experience repeated ankle sprains and pain due to an issue known as a coalition. This issue typically does not cause symptoms. Pain related to a coalition can come on gradually or suddenly, often after an ankle sprain. Activities like running, jumping, or standing for a long period can make the pain worse, while rest usually relieves it. The pain can be located in various parts of the foot and ankle, including the area below the bony bump on the inner side of the ankle (medial malleolus), the ankle joint itself, the joint between the talus and navicular bones (talonavicular joint), the cavity on the outer side of the ankle (sinus tarsi), under the foot on the side of the talus bone when the foot is bent downward (plantarflexed talus), and over the muscles on the outer side of the lower leg (peroneal tendons). The pain can also be associated with calf pain caused by a tight muscle in the back of the calf (gastrosoleus muscle) leading to spasms in the peroneal muscles.

Upon examination, the foot may be angled outward (valgus) with the front part of the foot turned out (abduction). There can also be varying degrees of flattening of the arch on the inner side of the foot, which does not reform when standing on tiptoes or during a foot maneuver known as Jack’s test. The person might not be able to stand on the side of the foot. Movement of the joint beneath the ankle (subtalar joint) may be restricted or completely absent. The gastrosoleus complex might be tight, and lack of movement at the subtalar joint can lead to spasms in the peroneal muscles when the foot is forced to turn inward (inversion). An additional bony prominence might also be felt just below the medial malleolus, giving an appearance of a double medial malleolus.

Testing for Talocalcaneal Coalition

When diagnosing whether you have a condition called talocalcaneal coalition, there are several steps doctors typically take. This condition is a connection between two bones in the foot, the talus and the calcaneus, which normally are separate.

First, doctors may use a variety of X-ray views to look at the area in question. They could note what appears to be a “ball-and-socket” like structure in the ankle joint. They may also see a bulging part of the talus bone (called the “talar beaking”) which is sometimes due to unusual mechanical stress at a joint nearby. This particular sign is about 48% sensitive and 91% specific for identifying a talocalcaneal coalition.

Other signs spotted on these X-rays include: the “C sign” (an implied letter “C” made by the shape of the talus and another foot bone); the “absent middle facet sign” (likely representing a missing surface where two bones meet); and an enlarged-looking foot bone which can sometimes be referred to as the “Drunken Waiter sign”. These signs are each associated with differing levels of accuracy in diagnosing talocalcaneal coalition.

CT scans are then used to further assess and visualize the potential talocalcaneal coalition. This imaging can provide more detail about the foot and ankle’s bones, and can be particularly useful in preparing for surgery. CT scans aren’t as useful for identifying coalitions that aren’t made of bone, but they are very good at determining the location, size, and extent of the possible coalition. This data can even be used to determine the best surgical approach, if surgery is determined to be necessary.

A more advanced version of CT scan is the CT SPECT scan that can identify exactly where symptoms are coming from.

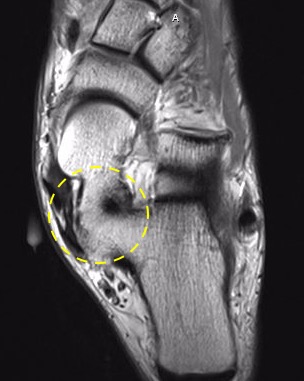

Additionally, MRI scans can be used to rule out certain types of coalition. Specifically, it’s good at identifying non-bone ones made of fibrous tissues or cartilage. MRI scans can also spot inflammation and others changes related to stress in nearby tendons–symptoms that often accompany talocalcaneal coalition.

Understandably, this can all sound quite complex. Rest assured, these evaluations are standard practice and help your doctor make the right decision about your treatment.

Treatment Options for Talocalcaneal Coalition

When a patient experiences discomfort due to a condition known as coalition, which refers to an abnormal connection between two bones in the foot or ankle, the first approach is usually to try non-surgical treatments. These are successful in relieving symptoms for around one-third of patients.

Non-Surgical Treatment

The goal of non-surgical treatment is to help ease the discomfort that comes with coalition. This can be particularly useful for patients whose symptoms are mild to moderate. A helpful approach can be to make changes to the patient’s footwear. Customized shoe inserts and arch supports can help to limit the movement of the affected joint in the foot and reduce the pressure that causes pain.

In addition to this, some methods to help relieve pain might include anti-inflammatory medications, steroid injections, or even wearing a below-knee cast to completely immobilize the foot for a period of about 6 weeks. This full immobilization can lead to symptom relief for about 30% of patients experiencing severe pain. If symptoms can be managed effectively with these non-surgical methods, the patient can slowly return to regular activities. The symptoms have a good chance of improving as the phase of bone growth, known as ossification, concludes, particularly if the heel is in a neutral position.

However, if these non-surgical treatments don’t provide relief, then the patient may need to be re-evaluated for potential surgical intervention. Surgery could be needed if the pain still persists and cannot be managed with non-surgical treatment or if the patient continues to experience recurrent ankle sprains.

Surgical Measures

1. Removal of the coalition: If the patient is less than 16 years old, surgically removing the coalition is often the preferred treatment. This includes removing the coalition itself and filling the space with a material such as fat, bone wax, tendon tissue, or a cartilage graft, to help prevent it from forming again. It’s important to also correct any deformity in the foot. If there’s a mild deformity, an insert might be placed in the sinus tarsi, a cavity on the side of the foot. Alternatively, adjustments may be made to the heel bone to correct the foot’s shape.

According to medical researchers Wilde et al., the success of the coalition resection depends on three conditions being met. First, the middle facet (a smooth, flat area on the bone) relative to the posterior facet (the facet at the back) should be less than 50%. Second, the posterior facet should have broad and thick cartilage with no signs of degeneration. Finally, the misalignment of the hindfoot, the back part of the foot including the heel, should be less than 16 degrees.

Another approach suggested by researchers Mubarak and Murphy is to ensure movement of the hindfoot is restored, regardless of the size of the coalition. If necessary, the removal of the coalition may be combined with lengthening of the calf or peroneal muscles. Most commonly, surgery fails due to incomplete removal of the coalition.

2. Subtalar fusion: This surgery is usually required if the area of the coalition is more than 50% of the talonavicular joint, located between the talus and the navicular, two bones in the foot. This involves joining together the two bones to prevent movement and reduce pain. A study showed that, using an arthroscopic (minimally invasive) procedure, about 81% of patients reported excellent outcomes a few years after the operation.

3. Triple fusion: This type of surgery is generally considered for those who have previously tried and failed other treatments and if degeneration (wear and tear) of other joints in the foot is also observed. This involves fusing together three joints – the subtalar, talonavicular, and calcaneocuboid joints – to restore functionality and reduce pain.

What else can Talocalcaneal Coalition be?

When a doctor suspects talonavicular coalition, they have to check for other conditions that could cause similar symptoms. These include:

- Calcaneonavicular coalition, which can be recognized by pain on the side of the foot and a specific pattern (‘anteater sign’) on medical images.

- Congenital vertical talus, a condition where the foot appears like a rocker-bottom and shows a vertical talus on images, and this doesn’t correct even when the foot is bent upwards.

- Calcaneovalgus foot, a deformity that occurs due to the position in the womb; it’s usually characterized by the foot tilting outwards and upwards. This can sometimes lead to flexible flat foot deformities when grown up.

- Pes planovalgus

- Accessory navicular bone, a condition that often presents as a painful flat foot.

- Tumors or rheumatoid arthritis in the joint under the ankle (subtalar joint).

What to expect with Talocalcaneal Coalition

The talocalcaneal coalition is a puzzling condition as symptoms don’t usually show until a child is around 12 to 15 years old. Flexible flat feet, a common condition in kids, usually correct themselves as a child grows and their feet take on the normal arch shape. In fact, most (75%) don’t show any symptoms and therefore, don’t need treatment.

However, a small number of kids who have rigid flat feet (i.e., flat feet that don’t develop an arch) that cause them discomfort or difficulty in walking need to be checked early on. This allows doctors to identify if a talocalcaneal coalition is the cause of their problems and leads to better treatment results.

The symptoms vary based on each patient and how much the fibrous tissue in their feet (referred to scientifically as ‘ossification’ or ‘metaplasia’) has changed into denser tissue (‘osseous synostosis’). Because this foot condition often gets diagnosed late, it decreases the chances of intervening early and possibly preventing more severe issues.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Talocalcaneal Coalition

If a talocalcaneal coalition, which is a connection between foot bones, isn’t treated, it usually limits the foot’s movement and can cause the hindfoot to lean outward over time. This happens because the foot’s inability to rotate outward during walking makes the heel bone adjust into a fixed, slanted position. Keep in mind, though, that this heel bone could also stay neutral or lean inward. Over time, the limited foot movement can cause wear and tear in various foot joints.

Some possible complications after the surgical removal of a talocalcaneal coalition include the coalition recurring, damage to specific areas and structures on the inside of the foot, repeated discomfort, superficial infections, minor wound issues, scar sensitivity, scar enlargement, and mild tingling sensation.

Most people report good results after surgery for removing a tarsal coalition, which is another type of bone connection in the foot. Over 70% of patients say they don’t have limits to their activities due to pain, and they have a good recovery in terms of function.

Common Side Effects:

- Reoccurrence of the coalition

- Damage to inner foot structures

- Persistent discomfort

- Superficial infections

- Minor wound problems

- Sensitivity of the scar

- Enlargement of the scar

- Mild tingling sensation

Recovery from Talocalcaneal Coalition

The steps taken to care for a patient after surgery to remove a tarsal coalition, a condition where two or more bones in the foot are abnormally connected, can vary based on different medical opinions shared in studies. Some experts suggest that patients start walking as soon as they feel comfortable, while others propose that the foot should not be used for 2 to 3 weeks.

Hubert and colleagues suggest that the patient should not use the foot for 2 weeks and then can start putting some weight on the foot for 4 weeks if the surgery included the placement of a graft, a piece of tissue inserted to replace or reinforce damaged structures. In their study, patients started physical therapy and were able to fully walk at 6 weeks.

Another type of surgery, subtalar joint arthrodesis, which is used to treat tarsal coalition affecting the medial facet, typically results in good outcomes with the patient not using the foot for 2 weeks followed by a gradual increase in the amount of weight placed on the foot over the next 6 weeks. According to some studies, patients go back to wearing regular shoes at around 8 to 12 weeks after the operation.

Mosca and Bevan discussed their method for an operation called calcaneal lengthening osteotomies for treating tarsal coalitions. This type of operation is also used for a condition called symptomatic flatfoot where the foot’s arch is very flat and causes foot pain. The patients in their study did not put weight on the foot for 8 weeks after this operation.

Preventing Talocalcaneal Coalition

In simple terms, teaching the patient and taking a careful yet mild approach can help avoid the need for surgery. This involves a few steps:

First, the patient should modify their activities, for example, by temporarily stopping any action that causes pain. Regularly stretching the calf muscles can also be beneficial, especially if the patient has a condition called Silverskiold. This condition affects the muscles and joints in the foot, and stretching can help manage it.

There are also certain medication options. For instance, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (or NSAIDs for short) such as ibuprofen or naproxen can be used when symptoms flare up. These drugs are designed to reduce inflammation and pain.

Using carefully chosen foot supports, also known as orthotics, can be helpful in managing mild to moderate deformities in the foot resulting from a condition known as subtalar coalition. This condition relates to an abnormal connection between the bones in the back of the foot.

If these steps don’t successfully manage the symptoms, then the next step is to evaluate the situation carefully and then decide on the right medical management plan. This typically involves several tests and assessments to better understand the patient’s condition and what the best way forward might be.